Preface

St. Sergius was born more than six hundred years ago, died more than five hundred. His calm, pure and holy life filled almost a century. Entering it as a modest boy Bartholomew, he left as one of Russia's greatest glories.

As a saint, Sergius is equally great for everyone. His feat is universal. But for a Russian it is precisely what excites us: deep consonance with the people, great typicality - a combination in one of the scattered features of Russians. Hence the special love and worship of him in Russia, the silent canonization into a national saint, which is unlikely to happen to anyone else. Sergius lived during the Tatar era. She didn’t touch him personally: the Radonezh forests covered him. But he was not indifferent to the Tatars. A hermit, he calmly, as he did everything in life, raised his cross for Russia and blessed Dimitri Donskoy for that battle, Kulikovo, which for us will forever take on a symbolic, mysterious connotation. In the duel between Rus' and Khan, the name of Sergius is forever associated with the creation of Russia.

Yes, Sergius was not only a contemplator, but also a doer. A just cause, that’s how it was understood for five centuries. Everyone who visited the Lavra, venerating the relics of the saint, always felt the image of the greatest beauty, simplicity, truth, holiness resting here. Life is “untalented” without a hero. The heroic spirit of the Middle Ages, which gave birth to so much holiness, gave its brilliant manifestation here.

It seemed to the author that now it was especially appropriate to have an experience - a very modest one - again, to the best of his ability, to restore in the memory of those who know and tell to those who do not know the works and life of the great saint and lead the reader through that special, mountainous country where he lives, from where he shines for us as an unfading star.

Let's take a closer look at his life.

Paris, 1924

The Life of Sergius of Radonezh as retold by Boris Zaitsev

Venerable Sergius of Radonezh

According to ancient legend, the estate of the parents of Sergius of Radonezh, the Rostov boyars Cyril and Maria, was located in the vicinity of Rostov the Great, on the road to Yaroslavl. The parents, “noble boyars,” apparently lived simply; they were quiet, calm people, with a strong and serious way of life.

Although Cyril more than once accompanied the princes of Rostov to the Horde, as a trusted, close person, he himself did not live richly. One cannot even talk about any luxury or licentiousness of the later landowner. Rather, on the contrary, one might think that home life is closer to that of a peasant: as a boy, Sergius (and then Bartholomew) was sent to fetch horses in the field. This means that he knew how to confuse them and turn them around. And leading him to some stump, grabbing him by the bangs, jumping up and trotting home in triumph. Perhaps he chased them at night too. And, of course, he was not a barchuk.

One can imagine parents as respectable and fair people, religious to a high degree. They helped the poor and willingly welcomed strangers.

On May 3, Maria had a son. The priest gave him the name Bartholomew, after the feast day of this saint. The special shade that distinguishes it lies on the child from early childhood.

At the age of seven, Bartholomew was sent to study literacy in a church school together with his brother Stefan. Stefan studied well. Bartholomew was not good at science. Like Sergius later, little Bartholomew is very stubborn and tries, but there is no success. He's upset. The teacher sometimes punishes him. Comrades laugh and parents reassure. Bartholomew cries alone, but does not move forward.

And here is a village picture, so close and so understandable six hundred years later! The foals wandered somewhere and disappeared. His father sent Bartholomew to look for them; the boy had probably wandered like this more than once, through the fields, in the forest, perhaps near the shores of Lake Rostov, and called to them, patted them with a whip, and dragged their halters. With all Bartholomew’s love for solitude, nature and with all his dreaminess, he, of course, carried out every task most conscientiously - this trait marked his entire life.

Now he - very depressed by his failures - found not what he was looking for. Under the oak tree I met “an elder of the monk, with the rank of presbyter.” Obviously, the elder understood him.

- What do you want, boy?

Bartholomew, through tears, spoke about his sorrows and asked to pray that God would help him overcome the letter.

And under the same oak tree the old man stood to pray. Next to him is Bartholomew - a halter over his shoulder. Having finished, the stranger took out the reliquary from his bosom, took a piece of prosphora, blessed Bartholomew with it and ordered him to eat it.

“This is given to you as a sign of grace and for the understanding of the Holy Scriptures.” From now on, you will master reading and writing better than your brothers and comrades.

We don’t know what they talked about next. But Bartholomew invited the elder home. His parents received him well, as they usually do with strangers. The elder called the boy to the prayer room and ordered him to read psalms. The child made the excuse of inability. But the visitor himself gave the book, repeating the order.

Then Bartholomew began to read, and everyone was amazed at how well he read.

And they fed the guest, and at dinner they told him about the signs over his son. The elder again confirmed that Bartholomew would now understand the Holy Scripture well and master reading.

After the death of his parents, Bartholomew himself went to the Khotkovo-Pokrovsky Monastery, where his widowed brother Stefan had already been monasticized. Striving for “the strictest monasticism”, for living in the wilderness, he did not stay here long and, having convinced Stefan, together with him he founded a hermitage on the banks of the Konchura River, on the Makovets hill in the middle of the remote Radonezh forest, where he built (about 1335) a small wooden church in the name of Holy Trinity, on the site of which now stands a cathedral church also in the name of the Holy Trinity.

Unable to withstand the too harsh and ascetic lifestyle, Stefan soon left for the Moscow Epiphany Monastery, where he later became abbot. Bartholomew, left completely alone, called upon a certain abbot Mitrofan and received tonsure from him under the name Sergius, since on that day the memory of the martyrs Sergius and Bacchus was celebrated. He was 23 years old.

Having performed the rite of tonsure, Mitrofan introduced Sergius to St. Tyne. Sergius spent seven days without leaving his “church”, prayed, did not “eat” anything except the prosphora that Mitrofan gave. And when the time came for Mitrofan to leave, he asked for his blessing for his desert life.

The abbot supported him and calmed him down as much as he could. And the young monk remained alone among his gloomy forests.

Images of animals and vile reptiles appeared before him. They rushed at him with whistling and gnashing of teeth. One night, according to the story of the monk, when in his “church” he was “singing matins,” Satan himself suddenly entered through the wall, with him a whole “demonic regiment.” They drove him away, threatened him, advanced. He prayed. (“May God rise again, and may His enemies be scattered…”) The demons disappeared.

Will he survive in a formidable forest, in a wretched cell? The autumn and winter snowstorms on his Makovitsa must have been terrible! After all, Stefan couldn’t stand it. But Sergius is not like that. He is persistent, patient, and he is “God-loving.”

He lived like this, completely alone, for some time.

Sergius once saw a huge bear, weak from hunger, near his cells. And I regretted it. He brought a piece of bread from his cell and handed it to him - since childhood, like his parents, he was “strangely accepting.” The furry wanderer ate peacefully. Then he began to visit him. Sergius always served. And the bear became tame.

But no matter how lonely the monk was at this time, there were rumors about his desert life. And then people began to appear, asking to be taken in and saved together. Sergius dissuaded. He pointed out the difficulty of life, the hardships associated with it. Stefan's example was still alive for him. Still, he gave in. And I accepted several...

Twelve cells were built. They surrounded it with a fence for protection from animals. The cells stood under huge pine and spruce trees. The stumps of freshly cut down trees stuck out. Between them the brothers planted their modest vegetable garden. They lived quietly and harshly.

Sergius led by example in everything. He himself chopped down cells, carried logs, carried water in two waterpots up the mountain, ground with hand millstones, baked bread, cooked food, cut and sewed clothes. And he was probably an excellent carpenter now. In summer and winter he wore the same clothes, neither the frost nor the heat bothered him. Physically, despite the meager food, he was very strong, “he had the strength against two people.”

He was the first to attend the services.

So the years passed. The community lived undeniably under the leadership of Sergius. The monastery grew, became more complex and had to take shape. The brethren wanted Sergius to become abbot. But he refused.

“The desire for abbess,” he said, “is the beginning and root of the lust for power.”

But the brethren insisted. Several times the elders “attacked” him, persuaded him, convinced him. Sergius himself founded the hermitage, he himself built the church; who should be the abbot and perform the liturgy?

The insistence almost turned into threats: the brethren declared that if there was no abbot, everyone would disperse. Then Sergius, exercising his usual sense of proportion, yielded, but also relatively.

“I wish,” he said, “it is better to study than to teach; It is better to obey than to command; but I am afraid of God's judgment; I don’t know what pleases God; the holy will of the Lord be done!

And he decided not to argue - to transfer the matter to the discretion of the church authorities.

Metropolitan Alexy was not in Moscow at that time. Sergius and the two eldest of the brethren went on foot to his deputy, Bishop Athanasius, in Pereslavl-Zalessky.

Sergius returned with a clear instruction from the Church to educate and lead his desolate family. He got busy with it. But he didn’t change his own life as abbess at all: he rolled the candles himself, cooked the kutya, prepared the prosphora, and ground the wheat for them.

In the fifties, Archimandrite Simon from the Smolensk region came to him, having heard about his holy life. Simon was the first to bring funds to the monastery. They made it possible to build a new, larger Church of the Holy Trinity.

From then on, the number of novices began to grow. They began to arrange the cells in some order. Sergius' activities expanded. Sergius did not tonsure his hair right away. I observed and studied closely the spiritual development of the newcomer.

Despite the construction of a new church and the increase in the number of monks, the monastery is still strict and poor. Everyone exists on their own, there is no common meal, pantries, or barns. It was customary for a monk to spend time in his cell either in prayer, or thinking about his sins, checking his behavior, or reading the Holy Scripture. books, rewriting them, icon painting - but not in conversations.

The hard work of the boy and young man Bartholomew remained unchanged in the abbot. According to the well-known testament of St. Paul, he demanded work from the monks and forbade them to go out for alms.

Sergius Monastery continued to be the poorest. Often there was not enough necessary things: wine for the liturgy, wax for candles, lamp oil... The liturgy was sometimes postponed. Instead of candles there are torches. Often there was not a handful of flour, bread, or salt, not to mention seasonings - butter, etc.

During one of the attacks of need, there were dissatisfied people in the monastery. We starved for two days and began to grumble.

“Here,” the monk said to the monk on behalf of everyone, “we looked at you and obeyed, but now we have to die of hunger, because you forbid us to go out into the world to ask for alms.” We’ll wait another day, and tomorrow we’ll all leave here and never come back: we can’t bear such poverty, such rotten bread.

Sergius addressed the brethren with an admonition. But before he had time to finish it, a knock was heard at the monastery gates; The gatekeeper saw through the window that they had brought a lot of bread. He himself was very hungry, but still ran to Sergius.

- Father, they brought a lot of bread, bless you to accept it. Here, according to your holy prayers, they are at the gate.

Sergius blessed, and several carts loaded with baked bread, fish and various foodstuffs entered the monastery gates. Sergius rejoiced and said:

- Well, you hungry ones, feed our breadwinners, invite them to share a common meal with us.

He ordered everyone to hit the beater, go to church, and serve a thanksgiving prayer service. And only after the prayer service he blessed us to sit down for a meal. The bread turned out to be warm and soft, as if it had just come out of the oven.

The monastery was no longer needed as before. But Sergius was still just as simple - poor, poor and indifferent to benefits, as he remained until his death. Neither power nor various “differences” interested him at all. A quiet voice, quiet movements, a calm face, that of a holy Great Russian carpenter. It contains our rye and cornflowers, birches and mirror-like waters, swallows and crosses and the incomparable fragrance of Russia. Everything is elevated to the utmost lightness and purity.

Many came from afar just to look at the monk. This is the time when the “old man” is heard throughout Russia, when he becomes close to Metropolitan. Alexy, settles disputes, carries out a grandiose mission to spread monasteries.

The monk wanted a stricter order, closer to the early Christian community. Everyone is equal and everyone is equally poor. Nobody has anything. The monastery lives as a community.

The innovation expanded and complicated the activities of Sergius. It was necessary to build new buildings - a refectory, a bakery, storerooms, barns, housekeeping, etc. Previously, his leadership was only spiritual - the monks went to him as a confessor, for confession, for support and guidance.

Everyone capable of work had to work. Private property is strictly prohibited.

To manage the increasingly complex community, Sergius chose assistants and distributed responsibilities among them. The first person after the abbot was considered the cellarer. This position was first established in Russian monasteries by St. Theodosius of Pechersk. The cellarer was in charge of the treasury, deanery and household management - not only inside the monastery. When the estates appeared, he was in charge of their life. Rules and court cases.

Already under Sergius, apparently, there was its own arable farming - there are arable fields around the monastery, partly they are cultivated by monks, partly by hired peasants, partly by those who want to work for the monastery. So the cellarer has a lot of worries.

One of the first cellarers of the Lavra was St. Nikon, later abbot.

The most experienced in spiritual life was appointed as confessor. He is the confessor of the brethren. Savva Storozhevsky, the founder of the monastery near Zvenigorod, was one of the first confessors. Later this position was given to Epiphanius, the biographer of Sergius.

The ecclesiarch kept order in the church. Lesser positions: para-ecclesiarch - kept the church clean, canonarch - led “choir obedience” and kept the liturgical books.

This is how they lived and worked in the monastery of Sergius, now famous, with roads built to it, where they could stop and stay for a while - whether for ordinary people or for the prince.

Two metropolitans, both remarkable, fill the century: Peter and Alexy. Hegumen of the army Peter, a Volynian by birth, was the first Russian metropolitan to be based in the north - first in Vladimir, then in Moscow. Peter was the first to bless Moscow. In fact, he gave his whole life for her. It is he who goes to the Horde, obtains a letter of protection from Uzbek for the clergy, and constantly helps the Prince.

Metropolitan Alexy is from the high-ranking, ancient boyars of the city of Chernigov. His fathers and grandfathers shared with the prince the work of governing and defending the state. On the icons they are depicted side by side: Peter, Alexy, in white hoods, faces darkened by time, narrow and long, gray beards... Two tireless creators and workers, two “intercessors” and “patrons” of Moscow.

Etc. Sergius was still a boy under Peter; he lived with Alexy for many years in harmony and friendship. But St. Sergius was a hermit and a “man of prayer”, a lover of the forest, silence - his life path was different. Should he, since childhood, having moved away from the malice of this world, live at court, in Moscow, rule, sometimes lead intrigues, appoint, dismiss, threaten! Metropolitan Alexy often comes to his Lavra - perhaps to relax with a quiet man - from struggle, unrest and politics.

The Monk Sergius came into life when the Tatar system was already breaking down. The times of Batu, the ruins of Vladimir, Kyiv, the Battle of the City - everything is far away. Two processes are underway, the Horde is disintegrating, and the young Russian state is growing stronger. The Horde is splitting up, Rus' is uniting. The Horde has several rivals vying for power. They cut each other, are deposited, leave, weakening the strength of the whole. In Russia, on the contrary, there is ascension.

Meanwhile, Mamai rose to prominence in the Horde and became khan. He gathered the entire Volga Horde, hired the Khivans, Yases and Burtases, came to an agreement with the Genoese, the Lithuanian prince Jagiello - in the summer he founded his camp at the mouth of the Voronezh River. Jagiello was waiting.

This is a dangerous time for Dimitri.

Until now, Sergius was a quiet hermit, a carpenter, a modest abbot and educator, a saint. Now he faced a difficult task: blessings on the blood. Would Christ bless a war, even a national one?

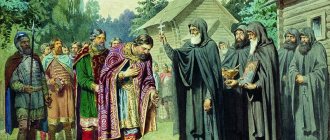

On August 18, Dimitri with Prince Vladimir of Serpukhov, princes of other regions and governors arrived at the Lavra. It was probably both solemn and deeply serious: Rus' really came together. Moscow, Vladimir, Suzdal, Serpukhov, Rostov, Nizhny Novgorod, Belozersk, Murom, Pskov with Andrei Olgerdovich - this is the first time such forces have been deployed. It was not in vain that we set off. Everyone understood this.

The prayer service began. During the service, messengers arrived - the war was also going on in the Lavra - they reported on the movement of the enemy, and warned them to hurry up. Sergius begged Dimitri to stay for the meal. Here he told him:

“The time has not yet come for you to wear the crown of victory with eternal sleep; but many, countless of your collaborators are woven with martyr’s wreaths.

After the meal, the monk blessed the prince and his entire retinue, sprinkled St. water.

- Go, don't be afraid. God will help you.

And, leaning down, he whispered in his ear: “You will win.”

There is something majestic, with a tragic undertone, in the fact that Sergius gave Prince Sergius two monks-schema monks as assistants: Peresvet and Oslyabya. They were warriors in the world and went against the Tatars without helmets or armor - in the image of a schema, with white crosses on monastic clothes. Obviously, this gave Demetrius’s army a sacred crusader appearance.

On the 20th, Dmitry was already in Kolomna. On the 26th-27th the Russians crossed the Oka and advanced towards the Don through Ryazan land. It was reached on September 6th. And they hesitated. Should we wait for the Tatars or cross over?

The older, experienced governors suggested: we should wait here. Mamai is strong, and Lithuania and Prince Oleg Ryazansky are with him. Dimitri, contrary to advice, crossed the Don. The way back was cut off, which means everything is forward, victory or death.

Sergius was also in the highest spirit these days. And in time he sent a letter after the prince: “Go, sir, go forward, God and the Holy Trinity will help!”

September 8th, 1380!

According to legend, Peresvet, who had long been ready for death, jumped out at the call of the Tatar hero, and, having grappled with Chelubey, struck him, he himself fell. A general battle began, on a gigantic front of ten miles at that time. Sergius correctly said: “Many are woven with martyr’s wreaths.” There were a lot of them intertwined.

During these hours the monk prayed with the brethren in his church. He talked about the progress of the battle. He named the fallen and read funeral prayers. And at the end he said: “We won.”

Rev. Sergius died on September 25, 1392.

Sergius came to his Makovitsa as a modest and unknown youth, Bartholomew, and left as a most illustrious old man. Before the monk, there was a forest on Makovitsa, a spring nearby, and bears lived in the wilds next door. And when he died, the place stood out sharply from the forests and from Russia. On Makovitsa there was a monastery - the Trinity Lavra of St. Sergius, one of the four laurels of our homeland. The forests cleared up around, fields appeared, rye, oats, villages. Even under Sergius, a remote hillock in the forests of Radonezh became a bright attraction for thousands. Sergius not only founded his monastery and did not act from it alone. Countless are the monasteries that arose with his blessing, founded by his disciples - and imbued with his spirit.

Trinity-Sergius Lavra

So, the young man Bartholomew, having retired to the forests on “Makovitsa”, turned out to be the creator of a monastery, then monasteries, then monasticism in general in a huge country.

Having left no writings behind him, Sergius seems to teach nothing. But he teaches precisely with his whole appearance: for some he is consolation and refreshment, for others - a silent reproach. Silently, Sergius teaches the simplest things: truth, integrity, masculinity, work, reverence and faith.

About St. Sergius of Radonezh, see also: S. Soloviev. Sergius of Radonezh Rev. Sergius of Radonezh Icon of St. Sergius of Radonezh in the work of the artist Nestorov Film for children Film “The Life of St. Sergius of Radonezh” A story about the appearance of the Most Holy Theotokos to St. Sergius of Radonezh