In recent years, interest in the Old Believers . Many both secular and ecclesiastical authors publish materials devoted to the spiritual and cultural heritage, history and modern day of the Old Believers. However, the phenomenon of the Old Believers itself, its philosophy, worldview and features of terminology are still poorly studied. about the semantic meaning of the term “ Old Believers ” in the article “ What are Old Believers? "

Dissenters or Old Believers?

This was done because the ancient Russian Old Believer church traditions, which existed in Russia for almost 700 years, were recognized as non-Orthodox, schismatic and heretical at the New Believer councils of 1656, 1666–1667. The term “ Old Believers ” itself arose forcedly. The fact is that the Synodal Church, its missionaries and theologians called the supporters of pre-schism, pre-Nikon Orthodoxy nothing more than schismatics and heretics.

Sergius of Radonezh In fact, such a greatest Russian ascetic as Sergius of Radonezh was recognized as non-Orthodox, which caused an obvious deep protest among believers.

The Synodal Church took this position as the main one and used it, explaining that supporters of all Old Believer agreements without exception fell away from the “true” Church because of their firm reluctance to accept church reform, which Patriarch Nikon and continued to one degree or another his followers, including Emperor Peter I.

On this basis, everyone who did not accept the reforms was called schismatics , shifting onto them the responsibility for the schism of the Russian Church, for the alleged separation from Orthodoxy. Until the beginning of the 20th century, in all polemical literature published by the dominant church, Christians professing pre-schism church traditions were called “schismatics,” and the very spiritual movement of the Russian people in defense of paternal church customs was called “schism.”

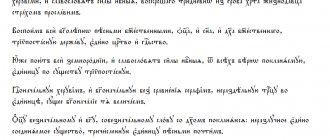

This and other even more offensive terms were used not only to expose or humiliate the Old Believers, but also to justify persecution and mass repressions against supporters of ancient Russian church piety. In the book “The Spiritual Sling,” published with the blessing of the New Believer Synod, it was said:

“The schismatics are not the sons of the church, but sheer heedless ones. They are worthy of being handed over to the punishment of the city court... worthy of all punishment and wounds. And if there is no healing, there will be death .

Changing attitudes towards the term “Old Believers” in society

However, by the end of the 19th century, the situation in society and the Russian Empire began to change. The government began to pay great attention to the needs and demands of the Old Orthodox Christians; a certain generalizing term was needed for civilized dialogue, regulations and legislation.

For this reason, the terms “ Old Believers ” and “Old Believers” are becoming increasingly widespread. At the same time, Old Believers of different consents mutually denied each other’s Orthodoxy and, strictly speaking, for them the term “Old Believers” united, on a secondary ritual basis, religious communities deprived of church-religious unity. For the Old Believers, the internal inconsistency of this term consisted in the fact that, using it, they united in one concept the truly Orthodox Church (i.e., their own Old Believer consent) with heretics (i.e., Old Believers of other consents).

Nevertheless, the Old Believers at the beginning of the 20th century positively perceived that in the official press the terms “schismatics” and “schismatic” began to be gradually replaced by “Old Believers” and “Old Believer.” The new terminology did not have a negative connotation, and therefore the Old Believer consents began to actively use it in the social and public sphere.

The word “Old Believers” is accepted not only by believers. Secular and Old Believer publicists and writers, public and government figures are increasingly using it in literature and official documents. At the same time, conservative representatives of the Synodal Church in pre-revolutionary times continue to insist that the term “Old Believers” is incorrect.

“Recognizing the existence of the “ Old Believers ,” they said, “we will have to admit the presence of the “ New Believers ,” that is, admit that the official church uses not ancient, but newly invented rites and rituals.”

According to the New Believer missionaries, such self-exposure could not be allowed.

And yet, over time, the words “Old Believers” and “Old Believers” became more and more firmly rooted in literature and in everyday speech, displacing the term “schismatics” from the colloquial use of the overwhelming majority of supporters of “official” Orthodoxy.

Russian Old Believers in the 19th century

The liberal policy of Catherine II and Paul I towards the Old Believers continued during the reign of Alexander I (1801-1825). In a circular letter to all provincial leaders dated August 19, 1820, the government’s tasks in relation to the Old Believers were formulated as follows: “Schismatics are not persecuted for the opinions of their sect related to faith, and can calmly adhere to these opinions and perform the rituals they have accepted, however, without any , public display of the teachings and worship of their sect... under no circumstances should they evade observing the general rules of improvement determined by laws.” Considering the Old Belief a sectarianism that should be completely eliminated over time, and calling the relaxations of the post-Petrine era “imaginary rights” of the Old Believers, the government of Alexander I, nevertheless, did not want to start new persecutions. The state legislation of this time clearly expressed the same principle by which the dominant church decided to establish unity of faith - “tolerance without recognition.”

In practice, the government’s policy was to “not notice” the Old Believers. The Old Believers also should not have once again been reminded of their existence. In order to avoid “causing a schism,” they were deprived of the opportunity to walk in religious processions around their churches even on Easter, and Old Believer priests did not have the opportunity outside the church to wear clothes appropriate to their rank. They could gather for common prayer, but in such a way that no one could see them; they could maintain a prayer room, but in such a way that it was impossible to determine from the appearance of the building or from the ringing of the bells that this was a temple. But despite this semi-legal situation, the Old Believers built a lot: new churches and even entire monasteries with numerous inhabitants appeared.

On February 17, 1812, the government tried to take more decisive action by issuing a decree “On allowing the Old Believers to have priests elected by the consent of parishioners by diocesan bishops, and not from priests of Irgiz monasteries, fugitive clergy who have discredited their rank.” This “permission” was nothing more than an attempt to forcibly convert all priests to the same faith. The government, apparently preparing to make adjustments to the policy towards the Old Believers, decided to evaluate its effectiveness. In a circular dated June 18, it demanded that governors secretly collect information about the number of Old Believers in their provinces and submit such data annually. The outbreak of the Patriotic War of 1812 delayed by a decade the enforcement of measures against the Old Believers, who, during severe military trials, showed numerous examples of selfless love for Russia.

During 1815-1816. Old Believers built chapels with domes and bells in Chuguev, Borovsk, Fatezh, the village of Kurlova, Kursk province, an almshouse with a chapel in Saratov, a convent with a church near Saratov. The government ordered to leave all these and other buildings, only to remove the domes and bells. In 1817-1825. a new wave of government decrees and orders marked the beginning of increased measures to oppress the Old Believers. First, a decree appeared prohibiting the construction of Old Believer chapels, churches, almshouses and monasteries. But, since the decree did not have the desired effect and construction was continued, on March 26, 1822, the government additionally issued an order: “Those schismatic churches that were built a long time ago should not be included in any further consideration and should be left without investigation... Do not build again not be allowed on any occasion."

In the same year, when approving this decree, the emperor made the following editorial amendment: “All schismatic churches, houses of worship and chapels built before 1817 are to be left inviolable without being searched; it is prohibited to build again.” If before this time there were no permitted Old Believer churches, but only “tolerated” ones, now “decreed” ones have already appeared, that is, permitted ones. However, all churches built after 1817 were destroyed. In 1822, it was also stated that fugitive priests who had converted to the Old Believers before this date would not be prosecuted for this.

With the beginning of the reign of Nicholas I (1825-1855), all thoughts of reform were already forgotten and an uncontrollable reaction reigned. The Old Believers lost all the benefits granted to them by the former kings: they were again deprived of citizenship rights, almost completely deprived of the priesthood and the opportunity to openly perform divine services. The first blow was directed against the Old Believer priesthood: on May 10, 1827, the Committee of Ministers forbade priests to move from one district to another to fulfill their requirements. In case of neglect of the prohibition, it was ordered to “treat them as vagabonds.” Nicholas I imposed a resolution on this decree: “Very fair.” By this measure it was planned to force the Old Believers, deprived for a long time of the opportunity to religiously organize their lives and even death, to convert to the same faith.

In the same year, the highest decision was made on the priests of the Rogozhsky cemetery, so as not to “accept new ones.” This order was later extended to all priestly parishes in Russia. In 1836, this instruction was confirmed with particular force regarding the Irgiz monasteries, where Old Believer priests mainly took refuge. A little earlier, another highest order regarding the Rogozhskoe cemetery indicated: “Do not allow so-called schismatic or fugitive priests coming from other places to remain in Moscow for any reason, and even less allow them to correct the requirements and temporarily stay at the Rogozhskoe cemetery.”

Following this, decrees appeared in general regarding the entire religious life of the Old Believers, both priests and non-priests. Laws are being adopted again depriving Old Believers of basic rights. Since 1834, Old Believers were prohibited from keeping registries (previously, extracts from them were a legal document and replaced a passport) - thus the Old Believers found themselves outside the law. Old Believer marriages were not recognized, and the children of Old Believers were illegitimate according to the laws of that time. They had no rights to either the inheritance or their father's surname.

To combat the Old Believers, the government created various “secret advisory committees” with a central committee in St. Petersburg, which were engaged in surveillance and controlled the life of Old Believers communities with the aim of suppressing and closing them. The committees consisted of the governor, the bishop, the chairman of the state estates and a gendarmerie officer. The very existence of such committees and their meetings had to remain secret.

Every year, the “restraint measures against the Old Believers” only increased: prayer houses and chapels built and decorated by the Old Believers began to be taken away and handed over to fellow believers. In 1835, a decree was issued dividing the Old Believers into: 1) the most harmful, which included sectarians and Old Believers who did not recognize marriages and prayers for the Tsar; 2) harmful - all other non-priests and 3) less harmful - priests.

Not only priests, but also prominent laymen were now sent into exile without trial and subjected to corporal punishment. This applied to all Old Believers, including entrepreneurs who began their trade with the very publication of Catherine’s Charter to the cities (1785), people whose factory and trading activities fed and provided work for hundreds of thousands of subjects of the empire. Laws of 1846-1847 Old Believers were prohibited from acquiring real estate and land, joining merchant guilds, and being elected to public positions. Entire Old Believer villages were placed under police surveillance.

However, the peak of Nicholas's reign was the destruction of Old Believer spiritual centers, unprecedented in its vandalism. In 1841, the Irgiz monasteries were destroyed and handed over to fellow believers. In 1853, a law was passed on the abolition of “illegal schismatic gatherings,” including monasteries and monasteries, according to which the altars of the Rogozhsky cemetery were sealed, part of the Transfiguration Monastery was transferred to co-religionists, and the Vygovsky hostel was generally closed and ruined. Volkovskaya and Malookhtinskaya almshouses in St. Petersburg were taken under government control. In pursuance of the new “draconian” laws, “many hundreds of prayer buildings were destroyed; tens of thousands of icons, this ancient property of our great-grandfathers, were selected; a huge library can be compiled from liturgical and other books taken from the chapels and houses of the Old Believers”20. Although now they were not burned for the old faith, as in the 17th century, there was still a case when living Old Believers were buried in the ground, beaten half to death.

“God knows,” writes the historian, “what these persecutions would have reached if the unsuccessful Crimean campaign had not forced the government to make a turn in domestic policy towards reforms”21. However, persecution could not break the followers of the old faith. The Old Believer merchant class grew and strengthened, and dynasties of merchants, industrialists and entrepreneurs known throughout Russia appeared (Morozovs, Guchkovs, Khludovs, Ryabushinskys). “They actively helped open new churches, almshouses, monasteries and monasteries. Mutual assistance and mutual assistance within the Old Belief were stronger than bureaucratic arbitrariness”22.

As a result, already during the reign of Alexander II (1855-1881), benefits, albeit very weak ones, were outlined for the Old Believers. In 1864, the tsar issued a decree on “the need to provide freedom in matters of faith.” In 1874, a new law was issued on Old Believer marriages, which began to be entered into special metric books under the police and those born from such marriages were considered already legitimate; and on May 3, 1883, a law appeared on the general position of the Old Believers in the state and its religious rights. The Old Believers were restored to those civil rights that they had lost under Nicholas I. In addition to economic freedoms, the construction of houses of worship and the performance of religious services were allowed. But preaching the Old Belief was still prohibited. However, this law, already very imperfect, was practically reduced to nothing in the next period.

The last quarter of the 19th century. and the beginning of the 20th century. (from 1880 to 1905) The Synod was headed by the notorious Chief Prosecutor K. P. Pobedonostsev. He was a supporter of the dictatorship of the New Believer Church in spiritual life and in this he saw the “salvation” of Russia. Freedom of conscience, the Chief Prosecutor argued, would lead to the fact that “the enemies will seize the Russian people in masses and make them Germans, Catholics, Mohammedans and others, and we will lose them forever for the church and the fatherland.” The “others” and enemies also included the Old Believers, who continued to be called “schismatics.”

Text author: Kirill Kozhurin

Material created: 06/22/2016

Changes in Nikon's church reform

Old Believer consents in Russia of the 20th century

Old Believer teachers, synodal theologians and secular scholars about the term “Old Believers”

Reflecting on the concept of “Old Believers,” writers, theologians and publicists gave different assessments. Until now, the authors cannot come to a common opinion.

It is no coincidence that even in the popular book, the dictionary “Old Believers. Persons, objects, events and symbols” (M., 1996), published by the publishing house of the Russian Orthodox Old Believer Church, there is no separate article “Old Believers” that would explain the essence of this phenomenon in Russian history. The only thing here is that it is only noted that this is “a complex phenomenon that unites under one name both the true Church of Christ and the darkness of error.”

The perception of the term “Old Believers” is noticeably complicated by the presence among Old Believers of divisions into “concords” (Old Believer churches), which are divided into supporters of a hierarchical structure with Old Believer priests and bishops (hence the name: priests - Russian Orthodox Old Believer Church , Russian Old Orthodox Church ) and into those who do not accept priests and bishops - non-priests ( Ancient Orthodox Pomeranian Church , Chapel Concord , runners (wanderer consent), Fedoseyevskoe consent).

LiveInternetLiveInternet

The split caused by Nikon's reforms did not just divide society into two parts and cause a religious war. Due to persecution, the Old Believers were divided into a great variety of different movements.

The main trends of the Old Believers are beglopopovshchina, clericalism and non-priesthood. Beglopopovshchina is the earliest form of Old Believers. This movement received its name due to the fact that believers accepted priests converting to them from Orthodoxy. From beglopopovshchina in the first half of the 19th century. The Concord of the Hours occurred. Due to the lack of priests, they began to be managed by charterers, who conducted services in the chapels.

Groups of priests are close to Orthodoxy in organization, doctrine and cult. Among them, co-religionists and the Belokrinitsky hierarchy stood out. The Belokrinitsky hierarchy is an Old Believer church that arose in 1846 in Belaya Krinitsa (Bukovina), on the territory of Austria-Hungary, and therefore the Old Believers who recognize the Belokrinitsky hierarchy are also called the Austrian Concord.

Bespopovshchina at one time was the most radical movement in the Old Believers. In terms of their religion, the Bespopovites moved further away from Orthodoxy than other Old Believers.

Dispute between a priest and a non-priest. Engraving. 1841 Fragment (State Historical Museum)

Various branches of Old Believers stopped appearing only after the revolution. However, by that time so many different Old Believer movements had arisen that even simply listing them was a rather difficult task. Our list does not include all representatives of Old Believer confessions.

Russian Orthodox Old Believer Church.

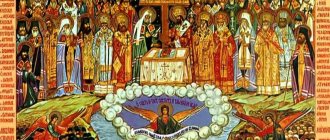

Consecrated Council of the Russian Orthodox Old Believer Church (October 16-18, 2012)

Today it is the largest Old Believer denomination: according to Paul, about two million people. Initially it arose around the association of Old Believers-Priests. Followers consider the Russian Orthodox Church to be the historical heir of the Russian Orthodox Church, which existed before Nikon's reforms. The Russian Orthodox Church is in prayerful and Eucharistic communion with the Russian Orthodox Old Believer Church in Romania and Uganda. The African community was accepted into the fold of the Russian Orthodox Church in May of this year. The Ugandan Orthodox, led by priest Joachim Kiimba, separated from the Patriarchate of Alexandria due to the transition to a new style. The rituals of the Russian Orthodox Church are similar to other Old Believer movements. The Nikonians are recognized as heretics of the second rank.

Lestovka is an Old Believer rosary. The word “lestovka” itself means ladder, ladder. A ladder from earth to heaven, where a person ascends through unceasing prayer. You finger the rows of sewn beads and say a prayer. One row - one prayer. And the ladder is sewn in the form of a ring - this is so that the prayer is unceasing. One must constantly pray so that the thoughts of a good Christian do not wander around, but are directed towards the divine. Lestovka has become one of the most characteristic signs of the Old Believer.

Distribution in the world: Romania, Uganda, Moldova, Ukraine. In Russia: throughout the country.

Common believers.

The second largest number of parishioners is the Old Believer denomination. Edinoverie are the only Old Believers who have come to a compromise with the Russian Orthodox Church.

Women and men of fellow believers stand in different parts of the temple, during censing they raise their hands in prayer, and the rest of the time they keep their hands crossed. All movements are kept to a minimum

This trend of priests arose at the end of the 18th century. The persecution of the Old Believers led to a serious shortage of priests among the Old Believers. Some were able to come to terms with this, others were not. In 1787, the Edinoverians recognized the hierarchical jurisdiction of the Moscow Patriarchate in exchange for certain conditions. Thus, they were able to bargain for the old pre-Nikon rituals and services, the right not to shave their beards and not wear German dresses, and the Holy Synod undertook to send them myrrh and priests. The rituals of the Edinoverie are similar to other Old Believer movements.

It is customary for fellow believers to come to church in special clothes for worship: a Russian shirt for men, sundresses and white scarves for women. A woman's scarf is pinned under the chin. However, this tradition is not observed everywhere. “We don't insist on clothes. People don’t come to church for the sake of sundresses,” notes Priest John Mirolyubov, the leader of the community of fellow believers.

Spreading :

In the world: USA. In Russia: according to the Russian Orthodox Church, there are about 30 communities of the same faith in our country. It is difficult to say exactly how many there are and where they are located, since fellow believers prefer not to advertise their activities.

Chapels.

The trend of the priests, which, due to persecution in the first half of the 19th century, was forced to turn into a non-priest movement, although the chapels themselves do not recognize themselves as non-priests. The birthplace of chapels is the Vitebsk region of Belarus.

Church of the Intercession of the Blessed Virgin Mary in Vereya

Left without priests, a group of Beglopopovites abandoned the priests, replacing them with lay leaders. Divine services began to be held in chapels, and this is how the name of the movement appeared. Otherwise, the rituals are similar to other Old Believer movements. In the eighties of the last century, some chapels from North America and Australia decided to restore the institution of priesthood and joined the Russian Orthodox Old Believer Church; similar processes are now observed in our country.

Chapels of the Nevyansk plant. Photos of the early 20th century

Spreading:

In the world: Australia, New Zealand, Brazil, USA, Canada. In Russia: Siberia, Far East.

Ancient Orthodox Pomeranian Church.

DOC is the modern name of the largest religious association of the Pomeranian consent. This is a non-priest movement, the Pomors do not have a three-rank hierarchy, Baptism and Confession are performed by laymen - spiritual mentors. The rituals are similar to other Old Believer faiths. The center of this movement was in the Vyzhsky Monastery in Pomorie, hence the name. The DOC is a fairly popular religious movement; there are 505 communities in the world.

In the early 1900s, the Old Believer community of the Pomeranian Consent acquired a plot of land on Tverskaya Street. A five-domed church in the “neo-Russian style” with a belfry was built on it in 1906 – 1908 according to the design of the architect D. A. Kryzhanovsky, one of the greatest masters of St. Petersburg Art Nouveau. The temple was designed using the techniques and traditions of the architecture of ancient churches in Pskov, Novgorod, Arkhangelsk .

Spreading:

In the world: Latvia, Lithuania, Belarus, Ukraine, Estonia, Kazakhstan, Poland, USA, Kyrgyzstan, Moldova, Romania, Germany, England. In Russia: Russian north from Karelia to the Urals.

Runners.

This non-popov movement has many other names: Sopelkovites, skrykniki, golbeshniks, underground workers. It arose at the end of the 18th century. The main idea is that there is only one way left for salvation: “have neither a village, nor a city, nor a house.” To do this, you need to accept a new baptism, break all ties with society, and evade all civil obligations.

Wanderer readers Davyd Vasilievich and Fyodor Mikhailovich. Photo. 1918

By its principle, running is asceticism in its most severe manifestation. The rules of the Runners are very strict, the punishments for adultery are especially severe. Moreover, there was not a single wandering mentor who did not have several concubines. As soon as it emerged, the current began to divide into new branches. Thus the following sects appeared:

Defaulters

They rejected divine services, sacraments and veneration of saints, and worshiped only certain “old” relics. They do not make the sign of the cross, do not wear a cross, and do not recognize fasts. Prayers were replaced by religious home conversations and readings. Communities of defaulters still exist in Eastern Siberia.

The Mikhailovsky plant in the Urals is one of the centers of defaulters

Hermits

They replaced wandering with removal to remote forests and deserts, where they organized communities, living according to such ascetic standards that even Mary of Egypt would have called too harsh. According to unverified information, communities of hermits still exist in Siberian forests.

Aaronites.

The non-popovian movement of the Aaronites arose in the second half of the 18th century.

Aaron. Mosaic in the Church of St. Sophia in Kyiv.

One of the leaders of the movement had the nickname Aaron, and after his “drive” they began to call this denomination. The Aaronites did not consider it necessary to renounce and withdraw from life in society and allowed marriage to be performed by a layman. They generally treated marriage issues very favorably; for example, they allowed combining married life and desert living. However, the Aaronites did not recognize the wedding performed in the Russian Orthodox Church and demanded a divorce or a new marriage. Like many other Old Believers, Aaron’s followers shunned passports, considering them “seals of the Antichrist.” It was a sin, in their opinion, to give any kind of receipt in court. In addition, the doubles were revered as apostates from Christ. Back in the seventies of the last century, several Aaron communities existed in the Vologda region.

Masons.

This priestless religious denomination has nothing in common with the Freemasons and their symbols. The name comes from the Old Russian designation for mountainous terrain - stone. Translated into modern language - highlanders.

All the scientists and researchers of this area were surprised at the qualities of the inhabitants. These mountain settlers were brave, courageous, determined and confident. The famous scientist K. F. Ledebur, who visited here in 1826, noted that the psychology of communities is truly something gratifying in such a wilderness. The Old Believers were not embarrassed by strangers, whom they saw less often, and did not experience timidity and withdrawal, but, on the contrary, showed openness, straightforwardness and even selflessness. According to the ethnographer A. A. Printz, the Altai Old Believers are a daring and dashing people, brave, strong, decisive, tireless. Source: https://www.kulturologia.ru/blo...

The masons were formed in the inaccessible mountain valleys of southwestern Altai from all sorts of fugitives: peasants, deserters. Isolated communities followed rituals characteristic of most Old Believer movements. To avoid close relationships, up to 9 generations of ancestors were remembered. External contacts were not encouraged. As a result of collectivization and other migration processes, masons dispersed throughout the world, mixing with other Russian ethnic groups. In the 2002 census, only two people identified themselves as bricklayers.

Kerzhaki.

The homeland of the Kerzhaks is the banks of the Kerzhenets River in the Nizhny Novgorod province. In fact, the Kerzhaks are not so much a religious movement as an ethnographic group of Russian Old Believers of the North Russian type, like masons, the basis of which, by the way, was the Kerzhaks.

Hood. Severgina Ekaterina. Kerzhaki

Kerzhaks are Russian old-timers of Siberia. When the Kerzhen monasteries were destroyed in 1720, tens of thousands of Kerzhaks fled to the east, to the Perm province, and from there they settled throughout Siberia, to Altai and the Far East. The rituals are the same as those of other “classical” Old Believers. Until now, in the Siberian taiga there are Kerzhatsky settlements that have no contact with the outside world, like the famous Lykov family. In the 2002 census, 18 people called themselves Kerzhaks.

Self-baptizers.

Self-baptizer. Engraving. 1794

This priestless sect differs from others in that its followers baptized themselves, without priests, through triple immersion in water and reading the Creed. Later, the self-baptizers stopped performing this “self-rite.” Instead, they introduced the custom of baptizing babies as midwives do in the absence of a priest. This is how the self-baptized people received a second name – grandmother’s. Self-baptized grandmothers disappeared in the first half of the 20th century.

Hole makers.

This is a movement of non-priest-self-baptists. The name of the sect appeared because of the characteristic way of praying. Dyrniks do not venerate icons painted after the church reform of Patriarch Nikon, since there was no one to consecrate them.

At the same time, they do not recognize “pre-reform” icons, since they were desecrated by “heretics”. To get out of their predicament, the hole-makers began to pray like Muslims, on the street facing east. In the warm season this is not difficult to do, but our winter is very different from the Middle East. It is a sin to pray while looking at the walls or a glass window, so hole piercers have to make special holes in the walls, which are plugged with plugs. Separate communities of hole makers exist to this day in the Komi Republic.

Fedoseevites.

The Fedoseevites are adherents of the priestless Old Believer movement. Their views are somewhat similar to those of modern Russian protesters.

Gifts to Napoleon. Preobrazhensky Fedoseevites send a bull and gold to the Kremlin as a gift to Napoleon in 1812. From an engraving

Fedoseevites are convinced of the historical depravity of the Russian state. In addition, they believe that the kingdom of the Antichrist has come and adhere to celibacy. The name arose from the name of the founder of the community - Feodosius Vasilyev from the family of Urusov boyars. The vow of celibacy did not prevent the community from attracting new supporters. For a hundred years - from the second half of the 18th to the second half of the 19th centuries, the Fedoseevites were the most numerous and influential movement in non-priesthood; communities appeared throughout the country. At the beginning of the 20th century, due to internal contradictions, the Fedoseevites were divided into several directions: the liberal Moscow (they accept “new wives” for confession, allow them to participate in services without making the sign of the cross), the conservative Kazansky (“new wives” are not accepted, sing and read in church only unmarried), Filimonovites and non-community members can.

They did not disappear even after the revolution. In 1941, in one of the centers of the Fedoseev movement, the village of Lampovo near Tikhvin, the Fedoseevites showed themselves to be malicious collaborators.

The text is based on the source: https://www.ridus.ru/news/1140…

Additions and selection of illustrations by B. Dneprov

Old Believers - bearers of the old faith

Some Old Believer authors believe that it is not only the difference in rituals that separates the Old Believers from the New Believers and other faiths. There are, for example, some dogmatic differences in relation to church sacraments, deep cultural differences in relation to church singing, icon painting, church-canonical differences in church administration, holding councils, and in relation to church rules. Such authors argue that the Old Believers contain not only old rituals, but also the Old Faith .

Consequently, such authors argue, it is more convenient and correct from the point of view of common sense to use the term “ Old Belief ,” which tacitly implies everything that is the only true one for those who accepted pre-schism Orthodoxy. It is noteworthy that initially the term “Old Belief” was actively used by supporters of priestless Old Believer agreements. Over time, it took root in other agreements.

Today, representatives of New Believers churches very rarely call Old Believers schismatics; the term “Old Believers” has taken root both in official documents and church journalism. However, New Believer authors insist that the meaning of the Old Believers lies in the exclusive adherence to the old rituals. Unlike pre-revolutionary synodal authors, current theologians of the Russian Orthodox Church and other New Believer churches do not see any danger in using the terms “Old Believers” and “New Believers.” In their opinion, the age or truth of the origin of a particular ritual does not matter.

The Council of the Russian Orthodox Church in 1971 recognized the old and new rites as absolutely equal in rights, equal in honor and equally saving. Thus, in the Russian Orthodox Church the form of ritual is now given secondary importance. At the same time, New Believer authors continue to instruct that the Old Believers, the Old Believers, are part of the believers who separated from the Russian Orthodox Church, and therefore from all of Orthodoxy, after the reforms of Patriarch Nikon.