History of the discovery of the relics

During his lifetime, the prince was a good politician and sovereign. Baptism radically changed his views on life and death. The adoption of the new faith helped to unite the people and abandon wild pagan rituals. Now he could not take revenge and kill, because his God spoke of love and forgiveness.

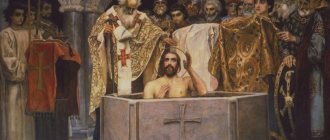

Icon of Saint Equal-to-the-Apostles Prince Vladimir

Vladimir died on July 15, 1015 in the village of Berestovoe, which was located near Kiev. On his deathbed, he asked the Lord for forgiveness for the fact that he had previously been a pagan and did not know the true God. Thus the great Russian saint departed to the Lord.

Read about Prince Vladimir:

- Icon of Saint Prince Vladimir

- Akathist to Saint Equal-to-the-Apostles Prince Vladimir

- Cathedral of St. Prince Vladimir in Kyiv

The prince was buried in the Tithe Church, which he built with his own money. Marble coffins with the bodies of Vladimir and his wife Anna were kept there until 1240.

In 1240, Kyiv was attacked by the army of Khan Batu. The temple was destroyed and the coffins were lost. And only in 1635 the relics were acquired thanks to the efforts of Metropolitan Peter Mohyla. The Metropolitan took the skull and arm bone. He transferred the chapter for storage to the Assumption Church of the Kiev Pechersk Lavra. The jaw was given to Tsar Mikhail Fedorovich as a gift, which he gave to the Assumption Cathedral in the Kremlin.

Now the jaw is in the Cathedral of Christ the Savior. The hand bone is in the Kiev St. Sophia Cathedral. The story with the skull is more complicated. During Soviet times, the skull from Kyiv was sent to Leningrad for examination. Anthropologist Mikhail Gerasimov had to reconstruct the portrait of the prince from the skull. But the war began, and the relic was lost in besieged Leningrad.

Interesting! It is assumed that the Soviet government had no intention of restoring the portrait of Grand Duke Vladimir, and the examination was a pretext for taking away the skull. After all, without the jaw, the examination was impossible. It was stored in Moscow, but no one was going to transfer it to Leningrad.

The Memorial Day of Saint Prince Vladimir is celebrated on July 28.

It is worth noting that Rus' reached the highest degree of its development precisely after Epiphany. Temples were built, Sunday schools were opened, books were copied, and later published. The Old Church Slavonic alphabet appeared, which still exists in the Russian Orthodox Church. Rus' became on a par with Constantinople. It was thanks to Vladimir that Rus' emerged from the shadow of sin and ignorance.

Not the saint Saint Vladimir: what the real biography of the Grand Duke hides

In the near future, the fate of the monument to Prince Vladimir should be decided, which, after active protests from Muscovites, was decided not to be erected on the observation deck of Moscow State University - now the monument the size of a 10-story building will have to find a new home in the capital. The 1000th anniversary of the death of the prince is celebrated on a grand scale - his relics are touring the regions of Russia these days (or rather, what is called his relics), this year several churches will be built in his honor (including in Moscow), in Key Russian museums will host exhibitions dedicated to him, and filming has already begun for a feature film in which Vladimir will be played by Danila Kozlovsky.

Meanwhile, based on the facts of Vladimir’s biography, it would be possible to make not just a film, but an entire “Game of Thrones”. Sergei Prostakov reminds readers of The Insider of some interesting episodes from the life of Vladimir Svyatoslavich, including the brutal murder of his brother, the destruction of Christian churches, the rape of a princely daughter in front of her parents, a harem of hundreds of concubines, a war against his son and many other educational historical details.

Almost a bastard

Probably, the Kiev prince Vladimir - the baptist of Rus' and the conqueror of the Pechenegs - is the most mysterious of the great rulers of Russian history. Hypotheses about the date of his birth vary greatly - from 942-955 to the 960s, but the very circumstances of his birth are even more curious. It is known that Prince Vladimir was born to the housekeeper of his grandmother Princess Olga, whose name was Malusha. Fragmentary information about this woman states that she was the daughter of a certain Malk Lyubechanin and the sister of one of the governors of Prince Svyatoslav Dobrynya. According to the laws of ancient Rus', key keepers, that is, servants who carried the master’s personal keys, due to the characteristics of their responsible profession, became personal slaves.

Princess Olga sent the housekeeper who became pregnant from Kyiv to a certain village of Budutino. There, Vladimir, who was born, according to Slavic custom, was raised until the age of three by his mother, whom Prince Svyatoslav, who was not getting out of the wars on the Danube at that time, seemed to have forgotten.

Being “from a slave” had a huge impact on Vladimir’s entire life. In many of the prince’s actions related to the conquest and retention of power, one can discern his desire to erase the memory of his origin. For opponents, the birth of a prince from a slave will be an important argument in challenging Vladimir’s right to own the gigantic eastern outskirts of the European world.

Later in medieval Europe the concept of a “bastard” - an illegitimate child of a monarch - was developed. But it is already characteristic of a fully Christianized continent. For still pagan Rus', polygamy was the norm, not to mention the presence of many illegitimate children for any prominent ruler. But Prince Vladimir was lucky: at the age of three, Princess Olga took him into his care, tearing his son away from his mother forever.

Traces of Malushi are lost in the darkness of history. According to one of the later legends, when Vladimir reigned in Novgorod, Malusha would live there as a famous witch and soothsayer throughout the European north, revered by the Slavs, Varangians and Chukhnos.

In the name of Perun

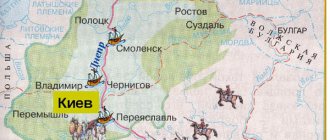

The name of Vladimir was first mentioned in connection with the events of 969. As already mentioned, Svyatoslav preferred military huts on the Danube to Kyiv's towers, where for years he waged wars with other Slavic princes and the Basileus of Constantinople. There he founded his new capital - Pereyaslav (today's Bulgarian city of Preslav). The Pechenegs, who were then roaming the Donetsk steppes, did not fail to take advantage of this. Kyiv found itself under siege, where “Olga shut herself up in the city with her grandchildren, Yaropolk and Oleg and Volodymer.” This foray did not bring the Pechenegs any military or diplomatic success, and they were forced to return home with nothing.

And in the same year, a message from Novgorod came to Svyatoslav on the Danube: local residents asked a descendant of Rurik to send them a ruler according to family tradition. Svyatoslav's choice fell on his youngest son Vladimir. The young prince, if we accept one of the named dates for the birth of Vladimir, was just a boy, accompanied by his uncle Dobrynya, he should have gone to the distant northern region.

The distant cold land was very different from the southern warm Kyiv. The Slavs came here not from the south, but from the west, through the Baltic states. Local cities and fortresses had much closer ties with Scandinavia than with the Dnieper lands. Largely because of this, there were almost no Christians here, although there were many representatives of various non-Slavic nationalities. The Normans who inhabited Scandinavia, who were called Varangians in Rus', were still northern pagans who kept the rest of Europe in fear for several centuries.

The city where Vladimir had to rule was the first Slavic fortress on the way “from the Varangians to the Greeks.” In these truly wild lands, the prince’s task was to demonstrate the presence of Kyiv power. However, news from the south to the north rarely reached, and mostly from second or third hands. The young prince was little worried about his father’s distant war on the Danube. But he made a large number of acquaintances among noble Varangian families, which in the future would allow him to take possession of the Russian south.

In the meantime, Vladimir decides for the first time in his life to undertake religious reform. The harsh climate and gloomy population required appropriate gods. Upon arrival in Novgorod, the young prince ordered the construction of a new temple for the thunder god Perun on the banks of the Ilmen River. For several decades to come, he will become the main deity of Vladimir’s entourage, with whose name on their lips they will burn cities and elevate their prince to the throne.

Brother's murder

Perun's patronage was needed very soon.

In 972, Prince Svyatoslav died: he and his squad ran into a Pecheneg ambush, which is believed to have been organized by agents of Constantinople. As soon as rumors of his death reached Kyiv, the eldest son of the murdered prince Yaropolk formally received political seniority among the other brothers.

Svyatoslav, who had little interest in internal affairs, preferred to distribute the lands under his control to his sons, each of whom began to feel like the sole master of their territories. After the death of his father, Yaropolk stopped his father’s war on the Danube, returned the status of “capital city” to Kyiv, and decided to demonstrate to his brothers who was the boss on Russian soil. Already in 975, Yaropolk went to the “Drevlyan lands” (modern Belarus), where Svyatoslav’s middle son Oleg ruled. The reason for the war between the brothers was the murder by Oleg of one of Yaropolk’s friends while hunting. This war did not last long. The Drevlyan army was completely defeated in the first battle, and Prince Oleg died in a stampede on a bridge near the fortress wall of the city of Ovruch.

News of the conflict reached Novgorod. It seems that Vladimir was impressed by Yaropolk’s quick victory, so he chose not to tempt fate and immediately fled to Scandinavia to join his friends. Yaropolk occupied Novgorod without resistance. In a few months, the goal of the entire century that had passed since Rurik’s calling was achieved - all of Rus' was under the command of the Kyiv prince.

Danila Kozlovsky as Prince Vladimir

Perhaps this would have been the beginning of a glorious reign, about which we would now know much more than about the unlucky youngest son of Svyatoslav and a slave. But history decreed differently. The long friendship with the Varangians was not in vain for Vladimir: in Scandinavia the fugitive prince quickly found allies. With the Varangian army he returned to Rus'. Novgorod was quickly taken. Vladimir did not execute Yaropolk’s governors, but together with them he conveyed a message to his brother: “Vladimir is coming at you, get ready to fight.”

Having a good political sense, Vladimir sets off with his army not directly to Kyiv, but to the Drevlyan lands, whose inhabitants had reason to dislike Yaropolk. There, the squad of the rich Polotsk went over to his side. On the wave of success, Vladimir decides to put aside military affairs for the sake of marriage. The decision was far-sighted: in order to gain a foothold among the Drevlyans, the young prince needed to become related to a local noble family. As his next wife, he chooses Rogneda, the beautiful daughter of the Polotsk prince Rogvold.

At this moment, Vladimir’s plans could once again go to waste. Rogneda refused the Novgorod prince in the most humiliating way. She publicly called him the son of a slave, which, as a representative of a noble Scandinavian family, did not stop her from marrying a bastard. But she wanted to marry his older brother, Yaropolk. Rogvold did not oppose this decision of his daughter: he was rich and had many allies to pay attention to Vladimir.

Vladimir did not forgive this. The once allied Polotsk was taken by his army and destroyed.

Following the advice of his mentor, Vladimir raped Rogneda in front of her parents.

The fate of the ruling dynasty in Polotsk was terrible. Rogvolod, his wife and sons were killed. But before doing this, Vladimir’s uncle and mentor, Dobrynya, decided to humiliate and dishonor them in retaliation for the insult. “And Dobrynya reviled Rogvolod and his daughter, and called her a little maid, and ordered Vladimir to be with her before his father and mother,” the Laurentian Chronicle reports. And, following the advice of his mentor, Vladimir raped Rogneda in front of her parents. “And he called her name Gorislava.”

Excited by the Polotsk failure, Vladimir did not waste time and set off with his Varangian army to Kyiv. Yaropolk was not ready for battle, so he closed himself in the city, hoping to wait out the siege. Vladimir, in turn, was not ready for a long siege: the newcomer Varangians fought only for the opportunity to plunder the captured cities. Therefore, I had to resort to cunning. Vladimir bribed the governor Yaropolk Blud. He persuaded Yaropolk to flee from Kyiv to the town of Roden, where Vladimir’s ambush awaited him. Yaropolk and his retinue were returned to Kyiv, brought to the tower courtyard of his father and, more recently, his own, but now Vladimir was in charge there. When Yaropolk entered the doors leading to Vladimir’s chambers, two Varangians standing in the doorway lifted him “under their bosom” onto their swords. Blud, who relentlessly followed the prince, quickly closed the doors, preventing Yaropolk’s people from breaking in.

After the death of Yaropolk, most of his warriors Yaropolk resignedly went over to the side of Vladimir. Yaropolk, as it turned out, had only one faithful confidant - governor Varyazhko, who, after the death of the prince, went to the Pechenegs. During the reign of Vladimir Varyazhko led the Pechenegs to Rus' to plunder and burn cities, avenging Yaropolk.

Vladimir forcibly made Yaropolk’s pregnant wife his concubine. The fact that she was pregnant is important; her son, Svyatopolk, who was born to her, will still play a role in the last years of Vladimir’s life.

Perunization of Rus'

Vladimir reached Kyiv with an army of Varangians and an almost equally numerous army of concubines. The Varangians reached Kyiv with him only because he allowed them to plunder the Slavic lands. Giving Kyiv up for plunder meant that he would once again be reminded of his origins, casting doubt on his inheritance right, and this would be an excellent reason for an uprising of the townspeople. Vladimir got out of the situation quite cleverly: he lured the most intelligent and far-sighted Varangians into his service, and deceived the rest into Constantinople, promising them quick work there. But ahead of the Varangian ships, Vladimir’s message to the Byzantine basileus flew: “Don’t keep them in the city, they will do evil, scatter them separately to different places and, most importantly, don’t let a single one back.” Thus, Vladimir shifted the solution of his problems to Constantinople, and at the same time providing him with military assistance.

“He was insatiable in fornication, bringing to himself married wives and corrupt girls”

He distributed hundreds of his concubines, collected in Novgorod, in Scandinavia and during the road to Kiev, among his residences: “300 in Vyshgorod, and 300 in Belgorod, and 200 in Berestovoy, in the village.” Even having such a harem at his disposal (and this in addition to five legal, or, as they said in ancient Rus', “led” wives), he could not (or did not want) to pacify his lust: “He was insatiable in fornication, bringing married wives to himself and corrupting maidens,” a monk chronicler wrote with undisguised condemnation about the Baptist of Rus' in the 11th century.

He built pagan temples from destroyed temples, mosques, and synagogues.

Paganism not only enabled Vladimir to lead a lifestyle so pleasing to him (polygamy was a sign of strength and status, and noisy feasts played a largely ritual role), it also helped him strengthen his power. The Joachim Chronicle (beginning of the 11th century) clearly gives the answer why Vladimir’s brother lost relatively quickly: “Yaropolk was unloved by people because he gave Christians great freedom.” Vladimir waged war on Christianity, Judaism and Islam, whose preachers then traveled throughout Rus' from end to end. He built pagan temples from destroyed temples, mosques, and synagogues.

Vladimir decided to reform the Slavic pantheon. The essence of this attempt was that idols of all significant pagan gods from different lands under his control were installed in Kyiv: Perun, Khors, Dazhdbog, Stribog, Simargl and Mokosha. The gods of the Slavic tribes seemed to be equalized, but Vladimir, who strived for autocracy, especially singled out, as was said, Perun.

Descriptions of a wooden idol with a silver head, towering over the Dnieper, have reached us. Perun was depicted as a man with a long mustache, which was considered a sign of princely dignity. Vladimir was not particularly shy about comparing himself to the thunder god.

The first ten years of Vladimir's reign are the time of transformation of Rus' into a state with many of its characteristic attributes: clear borders, fixed taxes, horizontal and vertical management verticals. These ten years are a time of military victories. The Poles were expelled from the western borders of Rus'. The rebellious Radimichi and Vyatichi submit to Kyiv. Vladimir's army is attempting to expand its influence in the Baltic states. An honorable peace was achieved with the Muslim Volga Bulgars.

But the “Perunization” of Rus' failed. Communication between the regions of Rus' had certain difficulties in those days, so the installation of idols of all significant gods in Kyiv meant little for Polotsk, Novgorod and Rostov. And the idols of Perun, installed throughout Rus', were rightly perceived as an attempt by Kyiv to impose its will. Considerations of international prestige and the spread of Kyiv's influence on neighboring countries, in turn, required the adoption of one of the major religions that were popular among Vladimir's subjects.

Baptism by fire and sword

Christianity was the best fit - it was already professed by many Slavic peoples at that moment, Vladimir’s mother, Princess Olga, was a Christian, and in general, the Russian lands had a lot in common with Christian Byzantium - both politically and economically. This connection could be used to advantage. Shortly before his baptism, Vladimir sent a large army to Byzantium, thanks to which the Byzantine government defeated the rebellious commander Varda Phocas. In exchange for this help, the prince demanded that the Byzantine princess Anna marry him. In response, a counter-demand was put forward: the groom must be baptized. Vladimir made the decision to change his faith easily. The Greek priest Paul came to Kyiv and performed the baptismal ceremony. The newly converted Christian received the name Vasily.

But at that moment the famous Byzantine treachery made itself known: they “forgot” to send the bride to Kyiv. In response to this, God's servant Vasily led an army to Crimea, where the Greek city of Korsun-Chersonese was then located in the area of modern Sevastopol. There he defiantly demanded that the local mayor give up his daughter for him instead of the princess. Vladimir’s logic was simple: if Constantinople refuses to baptize Rus', then let Korsun-Chersonese, incomparably less influential in Kyiv and more independent of the basileus, do it. But even here in Crimea, the prince received another refusal from a woman.

The mayor's family was executed in full, and he gave his daughter to one of the people who opened the gates for his army

As we know, Vladimir took such refusals painfully. The city was placed under a long siege. When the famine began, among the townspeople there were many supporters of immediate surrender. The gates were open. The old Polotsk scenario was repeated almost exactly: the mayor’s family was executed in its entirety, and he gave his daughter to one of the people who opened the gates for his army.

In the western part of the city, near the so-called “basilica on the hill,” an entire cemetery was discovered and explored, including a complex of mass graves with mass graves (about ten graves in total, each containing 30-40 people). According to one version, victims of the siege of Korsun are buried in the graves. It is noteworthy that one of the excavated graves is filled mainly with skulls. If archaeologists’ assumption about the connection of this necropolis with Vladimir’s Korsun campaign is correct, then these are traces of the massacre committed by Vladimir’s soldiers against the inhabitants of the city: pagan Rus threw the heads of executed Chersonites into the grave.

After the capture of Korsun, Vladimir again demanded that Byzantium give him Anna as his wife, threatening that otherwise Constantinople would be dealt with in the same way as Korsun. Byzantium conceded. Princess Anna was married to Vladimir in 988. (All these events for the current Russian authorities serve as a reason to claim that Rus' was baptized from Crimea).

The baptism of Rus' did not take place calmly everywhere; in some places residents showed resistance. In 991, Vladimir sent his thousand-man Putyata to Novgorod to pacify the rebels.

According to the Joachim Chronicle, he managed to break into the city and capture the leaders of the uprising, but by then the entire city had already risen - Putyata was surrounded and the churches began to be burned. Dobrynya came to the rescue - in order to divert the attention of the rebels, he set the city on fire. For the residents, the fire was worse than the war, so they rushed to save their homes. Dobrynya freed Putyata from the siege without interference, and soon Novgorod ambassadors came to the governor asking for peace. This is where the popular proverb comes from: “Those who baptize with the sword, and Dobrynya with fire.” It’s just that what is true from this chronicle, and what is fiction is unknown. However, archaeologists managed to find out that in 989 - that is, in the very year when, apparently, the baptism of Novgorodians took place - a severe fire actually raged in the city, during which the houses of Christians living on the Sofia side of the city were damaged. Archaeologists also discovered treasures of coins buried in a hurry by Christian Novgorodians; these treasures were never dug up by the owners, who apparently died in the fire. Traces of a fire were also found near Volkhov - where, according to the Joachim Chronicle, Dobrynya landed with his people. Thus, it can be argued that the baptism of Novgorod was indeed accompanied by mass riots, fires and pogroms, in which both Christians and pagans suffered.

Northeastern Rus' was finally baptized only a century and a half after the death of Prince Vladimir

In the lands of northeastern Kievan Rus, where modern Russia would begin to take shape in a few centuries, Christianity took root for a long time and reluctantly. Little is known about these events; we are mainly informed about them by later chronicles, written after the emergence of the Moscow state. Thus, the Nikon Chronicle of the 16th century claims that in 991, Prince Vladimir personally went to the Suzdal land, “and baptized everyone there.” “And Vladimir founded a city there in his name on the river on the Klyazma, and in it he built a wooden church of the Most Pure Mother of God.” But these testimonies of the 16th-century chronicler do not inspire confidence in modern historians, since they mention clergy who lived earlier or much later than the events described: the legendary Kiev metropolitans Michael and Leon, Patriarch Photius, bishops Nikita of Belgorod and Neophyte of Chernigov. All these historical distortions in the 16th century were needed for the sole purpose of making the Christian history of the young Moscow state more ancient. Today, researchers are inclined to believe that northeastern Rus' was finally baptized only a century and a half after the death of Prince Vladimir.

Most of Vladimir's sons, when they sat down to reign in the cities, brought with them a whole staff of clergy. But they were not always able to persuade local residents to even outwardly accept the faith. For example, the Rostov land was never baptized either by the first Rostov prince Yaroslav Vladimirovich, or by his brother Boris, whom Vladimir put in charge when he sent Yaroslav to Novgorod. The first Rostov bishops Theodore and Hilarion fled the city, unable to bear the hostility of the local population. In the middle of the 11th century, Bishop Leonty came under attacks from the pagans, and was eventually executed by them after one of the anti-Christian uprisings.

In the Life of one of the Rostov ascetics, Abraham, who lived in the 12th century, an interesting fact is reported. In Rostov, a stone idol of the god Veles continued to stand, which was quite openly worshiped by local residents with the full connivance of the authorities.

A similar situation occurred in Murom. Christian preaching was also not popular here. And the future first Russian holy prince Gleb Vladimirovich fled from the city, since it was inhabited entirely by pagans. Only Vladimir’s descendant, Prince Konstantin, made considerable efforts to ensure that by the end of the 12th century the population of Murom became Christian, for which he was subsequently canonized.

Things were no better in the Oka basin. The Vyatichi who lived along its banks were also baptized en masse only in the 12th century. At the beginning of this century, the Vyatichi killed the local priesthood for their zeal in Christian preaching.

The first Christian in Rus'

It is now quite difficult to accurately understand the reasons for the change in Vladimir’s personal behavior after the events of 988. Believers will call this insight, the acquisition of true faith. To critics of religion, this may seem like a well-orchestrated political spectacle, or even madness. But the fact remains: Vladimir spends the next quarter century of his reign as a fanatical supporter of Christianity. The extent to which the zeal of the Christian neophyte reached is demonstrated by an episode captured in the “Chronicle” of Bishop Thietmar of Merseburg, who notes that after baptism the prince specially collected doctors who were supposed to curb his flesh without resorting to the most radical method.

Vladimir also decided to give a tenth of his, and therefore state, income to the benefit of the church. This custom was preserved by Vladimir’s numerous heirs until the Mongol-Tatar invasion in the middle of the 13th century. The prince actively distributed land for the ownership of churches, monasteries and bishops' houses, which, given the general socio-economic rise in Rus' at the beginning of the 11th century, allowed the church to quickly grow rich. It is fair to note that these processes also contributed to the spread of education and the development of engineering and art.

However, the end of Vladimir’s life was marked by Rus'’s involvement in yet another civil strife. From his previous riotous lifestyle, he had 11 recognized sons, each of whom claimed his own part of the power. The situation was aggravated by the fact that in the last years of his life, Vladimir was probably going to change the principle of succession to the throne and bequeath power to his beloved son Boris (in any case, it was Boris who he entrusted with his squad). The two eldest surviving sons - Svyatopolk and Yaroslav - almost simultaneously rebelled against their father.

In 1014, Svyatopolk set out to oppose his father. He was married to the daughter of the Polish prince Boleslav (this dynastic marriage was the result of the peace agreements that ended the war with Poland in 1013). Svyatopolk, thus, in his speech against his father could hope for the support of Poland, and besides, he had direct grounds to lay claim to the throne, because his real father, as we remember, was Yaropolk, Vladimir’s elder brother. At the time of his birth, according to the traditions of that time, he was considered the son and heir of Vladimir. But by appealing to Christian traditions, he could still declare himself the son of Yaropolk, and therefore have more rights to the throne.

One way or another, the conspiracy was discovered. Vladimir hastened to take Svyatopolk and his Polish wife into custody. But the very next year another son spoke out against him.

The elderly baptist of Rus' was gathering a large army for war against his son.

In 1015, his son Yaroslav (the son of that same raped Rogneda) rebelled in Novgorod, who did not want to pay tribute to distant Kyiv. The elderly baptist of Rus' was gathering a large army for war against his son. The son began to gather an army in response, calling on the Varangians for this (exactly as this father once did, declaring war on his older brother). Numerous Scandinavian mercenaries - Danes, Swedes, Norwegians - arrived in Novgorod and awaited the signal to march. It is difficult to predict in whose favor the battle would have ended, but it never took place. At the beginning of 1015, Vladimir fell ill and died on July 15. Ancient Rus' is plunging into a period of bloody civil strife.

Canonization

There is no exact data on the time of canonization of Prince Vladimir. Only in the 14th century in the lands of the former Kievan Rus did they begin to venerate Vladimir as an equal-to-the-apostles saint. This had its own political conjuncture. Byzantium was rapidly declining, and the holiness of the Russian prince, one of the founders of the dynasty, made it possible to lay claim to the sanctification of the royal power of the Rurikovichs. However, the cult of Vladimir did not go much beyond the walls of the princely chambers. People recognized as saints those who experienced miracles during their lifetime; Vladimir had none documented.

Only in 1635 did the Kiev Metropolitan Peter Mohyla acquire the “imperishable” relics of the prince. And in Kyiv itself, throughout the 17th century, his name was actively distributed in liturgical books.

Since the Ukrainian priesthood was much more enlightened than the Russian, its influence, starting from the events of the Pereyaslav Rada and up to 1917, turned out to be very significant on national church history. Thanks to their efforts, the image of the holy prince begins to spread throughout the Russian Empire. The assertion that the entire future Russia was baptized in Kyiv will become a powerful tool in the fight against the nationalism of the peoples of the western outskirts of the empire.

However, the first large-scale celebrations in honor of St. Vladimir took place only in 1888 in honor of the 900th anniversary of the Baptism of Rus'. His memory day, July 15, was turned into one of the most important Russian religious holidays - for this purpose the Synod issued a special resolution. In fact, Vladimir was truly revered as a saint at the state level only those three decades before the revolution. Now, after the annexation of Crimea, the state has again elevated him to the status of the main saint in Russian history, but for how long is an open question.

How to get to the Cathedral of Christ the Savior

The Cathedral of Christ the Savior is located near the Kremlin. Temple address: st. Volkhonka, 17.

The optimal route is from the Kropotkinskaya metro station, where route buses No. 15, 255, 33 pass. From Red Square, getting to the temple is not difficult. From Red Square you need to go to the Alexander Garden. From the Alexander Garden you need to go down to the Kremlin embankment and walk along the Patriarchal Bridge, which leads to the temple.

Relics of Equal-to-the-Apostles Prince Vladimir

Burial in the hallway

Of course, you can read everywhere that the body of Prince Vladimir rests in a sarcophagus in the Church of the Tithes that he founded. But this is already, as it were, his repeated burial. And initially he was buried in the vestibule of the princely house in Berestovo!

Here is how Karamzin describes this procedure according to the chronicles: “At night they broke out the floor in the entryway, wrapped the body in a carpet, lowered it down the ropes and took it to the Church of the Mother of God.” Karamzin explained this by saying that the courtiers did not want to make the prince’s death public before his son Boris, who was on a campaign against the Pechenegs, returned to Kyiv. They were afraid that another son, Svyatopolk, having learned about the death of his father, would quickly rush to Kyiv to seize the throne.

But this news is clearly refuted by others, also chronicles. Vladimir had shortly before deprived Svyatopolk, the eldest of his living sons, of the right to inherit the grand-ducal throne and even sent him to prison. However, the very fact that at the time of Vladimir’s death he was free shows that his father forgave him for his guilt. In addition, the death of Vladimir was completely unable to be kept secret, and Svyatopolk reigned in Kyiv with the obvious consent and sympathy of, if not all the people, then some part of it. And most importantly, his younger brother Boris unconditionally recognized Svyatopolk’s rights.

So, if Vladimir’s initial funeral in the hallway was a political trick, it was somehow very strange and, most importantly, useless.

The spirit of the householder must protect the house and its inhabitants

However, the described action - breaking the floor in the hallway and lowering the deceased into the resulting underground - exactly repeats the ancient Slavic funeral rite, very common in pagan times. The Czech Slavist Lubor Niederle writes about him in his famous work “Slavic Antiquities”.

There is often a misconception that pagan Slavic funerals are burning in a boat with abundant sacrifices (including human ones), which was described in detail by the Arab traveler Ibn Fadlan, who saw such a funeral in Volga Bulgaria in 922. However, Ibn Fadlan described the funeral of a noble Russian! But the Rus and the Slavs are not originally the same thing. Moreover, the Rus who ruled in Kyiv were completely glorified before the end of the 10th century, since their princes began to bear Slavic names: Svyatoslav, Yaropolk, Vladimir...

The oldest funeral custom of the Slavs (as well as many Indo-European peoples) was the burial of the deceased, if he was the head of the family, in the house itself. More precisely, under the house. It was believed that in this way the house and its inhabitants would always receive the protection of the deceased great ancestor.

In this case, in no case was it supposed to take the deceased out of the entryway, since along with the body his spirit would leave the house and may never come back. To preserve the spirit of the deceased in the house forever, a hole was made in the floor of the entryway, under which a hole was dug, where the body of the deceased was lowered.

Why the grave was made in the entryway, and not under the living quarters, is also not difficult to guess. The point is not in some hygienic views of the ancient Slavs, but in the belief that the spirit of the householder will thereby more reliably protect the home. The canopy, along with the hearth, was one of the sacred places in the house.

Pagan-Christian dual faith

Niederle writes that “the ancient custom of burying the dead near the house or in the house itself among the Slavs disappeared at the end of the pagan period; there is little evidence of this custom, at least archaeologically.” However, not a single ritual, as a rule, disappears immediately and completely; it is usually transformed into something else. The cessation of permanent burials under the canopy among the Slavs was caused by the spread of Christianity and the mutual compromise of the two religious traditions. It was imperative to pay tribute to the customs of the ancestors. And under no circumstances should you take the dead man out of the hallway!

Before Prince Vladimir was finally buried in a Christian manner, he was first buried in the usual Russian traditions. His burial under the porch was temporary, symbolic. Moreover, after the adoption of Christianity, the symbolic observance of the old funeral rite should have acquired special significance among the Slavs for some time. After all, the old pagan gods have not gone away. According to new, Christian views, they took the place of “demons.” And they had to be appeased, otherwise you never know... All the superstitious gestures that we repeat to this day, often without thinking - spitting over the shoulder, knocking on wood, etc. - are based on the same attempt to appease evil spirits.

So Prince Vladimir was buried twice - first according to a pagan rite, then according to a Christian one. One did not contradict the other. This phenomenon, called “dual faith” by historians, determined Russian culture right up to Batu’s invasion. And after Vladimir, for example, until the 12th century inclusive, many Russian princes were laid in the grave in sleighs - another relic of pagan cults.