| Archbishop Gabriel (Steblyuchenko) |

Gabriel (Steblyuchenko)

(1940 - 2016), Archbishop b. Ust-Kamenogorsk and Semipalatinsk In the world Steblyuchenko Yuri Grigorievich, was born on June 30, 1940 in the city of Kherson, in the Ukrainian SSR, into a worker-peasant family.

In 1958, after graduating from high school, he entered the Odessa Theological Seminary and at the same time became a novice at the Odessa Dormition Monastery.

In 1959, he was tonsured a monk and named in honor of the Great Martyr George the Victorious.

In 1962 he entered the Leningrad Theological Academy, from which he graduated in 1966 with a candidate of theology degree for his work “ Relationships of the Russian and Anglican Churches in the light of historical literature”

«.

On June 15, 1966, he was tonsured a monk and named in honor of the Archangel Gabriel by Metropolitan Nikodim (Rotov) of Leningrad, and on June 19 of the same year he was ordained a hierodeacon and assigned to serve in the city of Vyborg, Leningrad Region.

In 1966, he was a participant in the Christian Peace Youth Conference, which was held in Kuopio, Finland.

From January 20, 1967 [1] to August 15, 1968, he was secretary of the Russian Ecclesiastical Mission in Jerusalem in the rank of archdeacon.

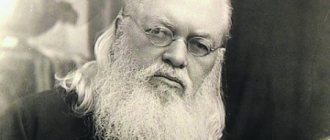

| Hieromonk Gabriel (Steblyuchenko), rector of the Transfiguration Cathedral in Vyborg, 1969 |

In 1968, at the end of a business trip abroad, he was ordained hieromonk by Metropolitan Nikodim (Rotov) of Leningrad and appointed rector of the Vyborg Transfiguration Cathedral.

On January 22, 1972, he was transferred to the Pskov diocese and appointed rector of the Trinity Cathedral in the city of Pskov and at the same time the responsible representative of the Pskov Metropolitan for welcoming foreign guests.

On April 7, 1974 he was elevated to the rank of abbot.

On April 7, 1975, he was appointed abbot of the Pskov-Pechersky Monastery in the city of Pechory, Pskov Region, with elevation to the rank of archimandrite.

“There were many complaints about his activities.

The monks, who held Gabriel responsible for the fatal incidents that occurred in the monastery, filed a complaint with Patriarch Pimen. Although the Patriarch removed Archimandrite Gabriel from his post, he was restored to it by the Deputy Chairman of the Council for Religious Affairs V. Furov, who specially came to the monastery” [2].

On July 19, 1988, he was elected Bishop of Khabarovsk and Vladivostok by the Holy Synod of the Russian Orthodox Church. The episcopal consecration took place on July 23 of the same year.

On January 31, 1991, he was temporarily removed from the management of the diocese by the Holy Synod “due to numerous complaints regarding the management of the diocese and moral character”

.

A synodal commission was appointed to investigate. On March 25 of the same year, he was found guilty, by the definition of the Holy Synod, “of violating the episcopal oath, expressed in accepting a banned clergyman of another diocese and granting him the right to officiate (Ap. 16), of violating church peace and an unworthy despotic attitude towards the clergy and laity ( Ap. 27, Dvukr. 9), in the lack of concern for the organization of diocesan and parish life (Ap. 36), in exceeding the powers of the ruling bishop, expressed in awarding his clergy with patriarchal church awards, in behavior discrediting the high title of bishop

. By a synodal decision, he was dismissed from the staff, banned from the priesthood for three years and sent for “prayer and complete repentance” to the Pskov-Pechersky Monastery under the supervision of a local bishop [3].

On July 18, 1991, by synodal decision, he was transferred to the Konevsky Mother of God-Nativity Monastery.

On April 21, 1994, he was appointed ruling bishop of the newly formed Blagoveshchensk and Tynda diocese.

He was a participant in the winter session of the Holy Synod of the Russian Orthodox Church in 2001-2002 [4].

On February 25, 2003, he was elevated to the rank of archbishop.

On October 5, 2011, he was transferred to the newly formed Ust-Kamenogorsk department. He did not arrive in the Ust-Kamenogorsk diocese [5].

On December 27, 2011, he was retired for health reasons in accordance with the submitted petition [6].

He died at about half past two on the night of May 20, 2021, in a hospital in the city of Blagoveshchensk, Amur Region, at the age of 76, after a serious illness, from a stroke [7]. On May 22 of the same year, a funeral service took place, which was led by Bishop Lukian (Kutsenko) of the Annunciation Cathedral in the city of Blagoveshchensk, co-served by numerous clergy. He was buried, according to his will, at the altar of the same cathedral [8].

Name day - July 13 (July 26 new style).

Awards

Church:

- Gaiter (1968)

- pectoral cross (August 19, 1971)

- Mace (April 7, 1974)

- Order of the Holy Apostles Peter and Paul, Antiochian Orthodox Church (1974)

- Order of Saint Equal-to-the-Apostles Prince Vladimir, III degree (1975)

- Order of St. Sergius of Radonezh, III degree (1980)

- Order of the Holy Blessed Prince Daniel of Moscow, II degree (1990)

- Order of St. Innocent, III degree (2000)

- Order of St. Seraphim of Sarov II degree (2005)

- commemorative medal “1020th anniversary of the Baptism of Rus'” (2008)

- Medal of Saint Equal-to-the-Apostles Prince Vladimir (2015)

Secular:

- honorary medal of the All-Russian Society for the Protection of Historical and Cultural Monuments (1986)

- Medal of Honor “For Peace Fighter” (1988)

- gold medal of the Soviet Peace Foundation (1990)

- State Order of Honor (No. 9965 dated August 11, 2000)

- honorary medal “For sacrificial service” from the Orthodox social movement “Orthodox Russia” (2001)

- badge “For Space Exploration” (2002, No. 115)

- medal “Alexy - a man of God” from the Union of Russian Cossacks (2001, No. 56)

- badge “200 years of the Ministry of Internal Affairs of Russia” (2002, No. 706)

Excerpt characterizing Gabriel (Steblyuchenko)

The previous order, introduced upon leaving Moscow, for captured officers to march separately from the soldiers, had long been destroyed; all those who could walk walked together, and Pierre, from the third transition, had already united again with Karataev and the lilac bow-legged dog, which had chosen Karataev as its owner. Karataev, on the third day of leaving Moscow, developed the same fever from which he was lying in the Moscow hospital, and as Karataev weakened, Pierre moved away from him. Pierre didn’t know why, but since Karataev began to weaken, Pierre had to make an effort on himself to approach him. And approaching him and listening to those quiet moans with which Karataev usually lay down at rest, and feeling the now intensified smell that Karataev emitted from himself, Pierre moved away from him and did not think about him. In captivity, in a booth, Pierre learned not with his mind, but with his whole being, life, that man was created for happiness, that happiness is in himself, in the satisfaction of natural human needs, and that all unhappiness comes not from lack, but from excess; but now, in these last three weeks of the campaign, he learned another new, comforting truth - he learned that there is nothing terrible in the world. He learned that just as there is no situation in which a person would be happy and completely free, there is also no situation in which he would be unhappy and not free. He learned that there is a limit to suffering and a limit to freedom, and that this limit is very close; that the man who suffered because one leaf was wrapped in his pink bed suffered in the same way as he suffered now, falling asleep on the bare, damp earth, cooling one side and warming the other; that when he used to put on his narrow ballroom shoes, he suffered in exactly the same way as now, when he walked completely barefoot (his shoes had long since become disheveled), with feet covered with sores. He learned that when, as it seemed to him, he had married his wife of his own free will, he was no more free than now, when he was locked in the stable at night. Of all the things that he later called suffering, but which he hardly felt then, the main thing was his bare, worn, scabby feet. (Horse meat was tasty and nutritious, the saltpeter bouquet of gunpowder, used instead of salt, was even pleasant, there was not much cold, and during the day it was always hot while walking, and at night there were fires; the lice that ate the body warmed pleasantly.) One thing was hard. at first it’s the legs. On the second day of the march, after examining his sores by the fire, Pierre thought it impossible to step on them; but when everyone got up, he walked with a limp, and then, when he warmed up, he walked without pain, although in the evening it was even worse to look at his legs. But he did not look at them and thought about something else. Now only Pierre understood the full power of human vitality and the saving power of moving attention invested in a person, similar to that saving valve in steam engines that releases excess steam as soon as its density exceeds a known norm. He did not see or hear how the backward prisoners were shot, although more than a hundred of them had already died in this way. He did not think about Karataev, who was weakening every day and, obviously, was soon to suffer the same fate. Pierre thought even less about himself. The more difficult his situation became, the more terrible the future was, the more, regardless of the situation in which he was, joyful and soothing thoughts, memories and ideas came to him. On the 22nd, at noon, Pierre was walking uphill along a dirty, slippery road, looking at his feet and at the unevenness of the path. From time to time he glanced at the familiar crowd surrounding him, and again at his feet. Both were equally his own and familiar to him. The lilac, bow-legged Gray ran merrily along the side of the road, occasionally, as proof of his agility and contentment, tucking his hind paw and jumping on three and then again on all four, rushing and barking at the crows that were sitting on the carrion. Gray was more fun and smoother than in Moscow. On all sides lay the meat of various animals - from human to horse, in varying degrees of decomposition; and the wolves were kept away by the walking people, so Gray could eat as much as he wanted. It had been raining since the morning, and it seemed that it would pass and clear the sky, but after a short stop the rain began to fall even more heavily. The rain-saturated road no longer absorbed water, and streams flowed along the ruts. Pierre walked, looking around, counting steps in threes, and counting on his fingers. Turning to the rain, he internally said: come on, come on, give it more, give it more. It seemed to him that he was not thinking about anything; but far and deep somewhere his soul thought something important and comforting. This was something of a subtle spiritual extract from his conversation with Karataev yesterday. Yesterday, at a night halt, chilled by the extinguished fire, Pierre stood up and moved to the nearest, better-burning fire. By the fire, to which he approached, Plato was sitting, covering his head with an overcoat like a chasuble, and telling the soldiers in his argumentative, pleasant, but weak, painful voice a story familiar to Pierre. It was already past midnight. This was the time at which Karataev usually recovered from a feverish attack and was especially animated. Approaching the fire and hearing Plato’s weak, painful voice and seeing his pitiful face brightly illuminated by the fire, something unpleasantly pricked Pierre’s heart. He was frightened by his pity for this man and wanted to leave, but there was no other fire, and Pierre, trying not to look at Plato, sat down near the fire. - How's your health? - he asked. - How's your health? “God will not allow you to die because of your illness,” said Karataev and immediately returned to the story he had begun. “...And so, my brother,” continued Plato with a smile on his thin, pale face and with a special, joyful sparkle in his eyes, “here, my brother... Pierre knew this story for a long time, Karataev told this story to him alone six times, and always with a special, joyful feeling. But no matter how well Pierre knew this story, he now listened to it as if it were something new, and that quiet delight that Karataev apparently felt while telling it was also communicated to Pierre. This story was about an old merchant who lived decently and God-fearingly with his family and who one day went with a friend, a rich merchant, to Makar. Stopping at an inn, both merchants fell asleep, and the next day the merchant's comrade was found stabbed to death and robbed. A bloody knife was found under the old merchant's pillow. The merchant was tried, punished with a whip and, having pulled out his nostrils - in the proper order, said Karataev - he was sent to hard labor. “And so, my brother” (Pierre caught Karataev’s story at this point), this case has been going on for ten years or more. An old man lives in hard labor. As follows, he submits and does no harm. He only asks God for death. - Fine. And if they get together at night, the convicts are just like you and me, and the old man is with them. And the conversation turned to who is suffering for what, and why is God to blame. They began to say, that one lost a soul, that one lost two, that one set it on fire, that one ran away, no way. They began to ask the old man: why are you suffering, grandpa? I, my dear brothers, he says, suffer for my own and for people’s sins. But I didn’t destroy any souls, I didn’t take anyone else’s property, other than giving away to the poor brethren. I, my dear brothers, am a merchant; and had great wealth. So and so, he says. And he told them how the whole thing happened, in order. “I don’t worry about myself,” he says. It means God found me. One thing, he says, I feel sorry for my old woman and children. And so the old man began to cry. If that same person happened to be in their company, it means that he killed the merchant. Where did grandpa say he was? When, in what month? I asked everything. His heart ached. Approaches the old man in this manner - a clap on the feet. For me, he says, old man, you are disappearing. The truth is true; innocently in vain, he says, guys, this man is suffering. “I did the same thing,” he says, “and put a knife under your sleepy head.” Forgive me, he says, grandfather, for Christ’s sake.

Notes[ | ]

- Priest

Gleb Yakunin. On the current situation of the Russian Orthodox Church and the prospects for the religious revival of Russia // Free Word. Issue 35-36. Frankfurt am Main: Posev, 1979. - pp. 12-13. - The last years of Brezhnevism, the reign of Andropov and Chernenko // Russian Orthodox Church in Soviet times (1917-1991)

- The first day of the winter session of the Holy Synod of the Russian Orthodox Church has ended

- The Holy Synod completed the first day of work at the renovated residence of the Patriarch of Moscow and All Rus' in the Danilov Monastery

- Decree of the President of the Russian Federation of August 11, 2000 No. 1491 “On awarding state awards of the Russian Federation” (unspecified)

. // Official website of the President of Russia. Date accessed: August 4, 2021.

Publications[ | ]

- 40th anniversary of the patriarchal communities in Finland // Journal of the Moscow Patriarchate. M., 1967. - No. 5. - P. 15-25. (co-author)

- Repeated Christian education is required / interview - answers: Gabriel, Bishop of Khabarovsk and Vladivostok // Journal of the Moscow Patriarchate. M., 1990. - No. 11. - P. 26-27.

- The temple is a prototype of the ideal state of the world and man // Journal of the Moscow Patriarchate. M., 1990. - No. 11. - P. 42-43

- Word at the consecration of the church in honor of the Annunciation of the Blessed Virgin Mary, on Relochny, in the city of Blagoveshchensk // Journal of the Moscow Patriarchate. M., 2003. - No. 8. - P. 64.

Biography[ | ]

Born on June 30, 1940 in Kherson. From a young age he attended the Cathedral of the Holy Spirit in Kherson and served at the altar during divine services.

In 1958, after graduating from high school, he entered the Odessa Theological Seminary, then the Leningrad Theological Academy, from which he graduated in 1966 with a candidate of theology degree for his work “Relationships of the Russian and Anglican Churches in the light of historical literature.”

On June 15, 1966, Metropolitan Niim (Rotov) of Leningrad and Ladoga tonsured him as a monk with the name Gabriel

- in honor of the Archangel Gabriel, on June 19 he was ordained as a hierodeacon and assigned to serve at the Transfiguration Cathedral in the city of Vyborg.

In August 1966, he participated in the Christian Youth Congress in Lohja, Finland. In 1967, he was part of the delegation at the celebrations marking the 40th anniversary of the Pokrovskaya and Nikolskaya communities of the Moscow Patriarchate in Helsinki.

From 1967 to August 1968 he was secretary of the Russian Spiritual Mission in Jerusalem.

In 1968, Metropolitan Niim ordained him as a hieromonk, was awarded a vestment and appointed rector of the Transfiguration Cathedral in Vyborg. On August 19, 1971 he was awarded the pectoral cross.

On January 22, 1972, he was appointed rector of the Trinity Cathedral in Pskov. On April 7, 1974, he was elevated to the rank of abbot and awarded the club.

Viceroy of the Pskov-Pechersky Monastery[ | ]

On April 7, 1975, with the blessing of His Holiness Patriarch Pimen, he was appointed abbot of the Pskov-Pechersky Monastery and elevated to the rank of archimandrite.

According to the report of the dissident, priest Gleb Yakunin, Archimandrite Gabriel, even during the years of his abbot in Pskov, had a reputation as an informer (“chief chief”) of the KGB, and “during his viceroyship he caused widespread discontent among monks, pilgrims, and believers, for, having become the viceroy, he led a policy of reducing attendance of believers at the monastery”[1].

In 1978, Patriarch Pimen issued an order to remove Archimandrite Gabriel. After this, V. G. Furov, deputy chairman of the Council for Religious Affairs under the Council of Ministers of the USSR, went to the monastery with an audit, as a result of which the decision was annulled[2].

Bishop[ | ]

By the determination of the Holy Synod of July 19, 1988, he was appointed Bishop of Khabarovsk and Vladivostok. The consecration took place on July 23, 1988.

By the decision of the Synod of January 31, 1991, he was temporarily removed from the administration of the diocese. By the decision of the Synod of March 25, 1991, he was dismissed from the staff and sent for complete repentance to the Pskov-Pechersky Monastery under the supervision of the local bishop. For 3 years it is not allowed to perform church services.

On April 21, 1994, he was appointed Bishop of Blagoveshchensk and Tynda.

On February 25, 2003, he was elevated to the rank of archbishop.

Member of the Public Chamber of the Amur Region (approved by decree of the regional governor).

On October 5, 2011, by decision of the Holy Synod, he was elected Archbishop of Ust-Kamenogorsk and Semipalatinsk (Kazakhstan Metropolitan District)[3].

On December 27, 2011, by decision of the Holy Synod, he was retired at his own request.[4]

On May 20, 2021, he rested in the city of Blagoveshchensk, buried near the altar of the cathedral in the city of Blagoveshchensk, Amur region.