How they prepared for Easter in Rus'

Throughout Holy Week, the peasants, as they say, tirelessly scrape off, wash and clean out the usual dirt of the working environment of poor people and bring their wretched homes into a clean and, if possible, elegant appearance.

From the very first days of Holy Week, men prepare bread and feed for livestock for the entire Bright Week, so that they don’t have to bother on the holiday and have everything at hand. And the girls are busy in the huts: whitening the stoves, washing the benches, scraping the tables, wiping the dusty walls with wet rags; sweep away the cobwebs.

The height of housework falls on Maundy Thursday. Having finished decorating the hut, the women usually start cooking. In rich houses, livestock is fried and boiled, Easter cakes are baked, decorated with marmalade, monpassier and other colored sweets. In poor families, this luxury is considered unaffordable, and here Easter cakes in the form of ordinary buns, without any baking, are bought from local shopkeepers or Kalashniks and Barashniks.

But since Kalashniks or Barashniks deliver their Easter cakes around the village about a week before the holidays, on the Easter table of a poor peasant there is usually a flat and hard bun, like wood, costing no more than five or two kopecks. But there are, however, cases when peasants cannot afford this luxury without going over budget.

Richer relatives usually come to the aid of such poor people, who, out of a sense of Christian charity, do not allow the Holy Holiday to be overshadowed by “hungry breaking of the fast,” especially in their related family.

However, strangers do not lag behind relatives, and on Good Friday it is not at all uncommon to see women walking around the village, delivering all sorts of supplies to the houses of the poor: one will bring milk and eggs, another will bring cottage cheese and Easter cake, and the third, lo and behold, will bring it under her apron and a piece of carnage, although he will punish him for not telling his husband.

As for middle-income men, although they do not resort to the help of wealthy neighbors, they rarely do without loans, and are even more willing to sell some of the village products (firewood, hay, crumpled hemp, etc.) in order to get money and eat a quarter or half a bucket of vodka, wheat flour for noodles and millet for porridge. But the money raised is spent carefully, so that there is enough money to “buy God” oil and candles and pay the priests.

Reading the Passion in Church

All household chores usually end by the evening of Holy Saturday, when people rush to church to listen to the reading of the “passion.” Reading the “passion” is considered an honor, since the reader can testify to his literacy in front of the entire people. But usually, most often, some pious old man reads, surrounded by listeners of men and a whole crowd of sighing women. This monotonous and sometimes simply inept reading lasts for a long time, and since the meaning of what is being read is not always accessible to the dark peasant mind, tired attention is dulled and many leave the reader to pray somewhere in the corner or light a St. Shroud or just sit somewhere in the vestibule and doze off. The latter happens especially often, and our correspondents from the clergy sharply condemn this disrespect for church services, noting that sleeping in a church, and even on the Great Night, means the same thing as completely not understanding everything that happens in the temple.

We, however, think that such rigorism can hardly be considered fair, since in our entire country not a single class has retained such faith as the peasantry. And we must take into account that these sleeping people are exhausted by the strict village fast, that many of them trudged from distant villages along the terrible spring road, and that, finally, they are all completely tired of the pre-holiday bustle and troubles. In addition, relatively few people sleep, while the majority crowd in the darkness of the church fence and are actively busy with the external decoration of the temple. Throughout the Easter night, talking and shouting can be heard here; people arrange tar barrels and prepare fires; boys in a fussy crowd run around the bell tower and place lanterns and bowls, and the bravest men and boys, at the risk of their lives, even climb onto the dome to illuminate it too. But now the lanterns are placed and lit, the whole church is illuminated with lights, and the bell tower burns like a gigantic candle in the silence of the Easter night. In the square in front of the church, a dense crowd of people looks and admires their decorated temple and loud enthusiastic screams can be heard. Then the first, drawn-out and ringing strike of the bell was heard, and a wave of thick, oscillating sound solemnly and majestically rolled through the sensitive air of the night. The crowd of people swayed, trembled, hats flew off their heads, and a joyful sigh of tenderness escaped from a thousand breasts. Meanwhile, the bell buzzes and buzzes, and people pour into the church to listen to Matins. After just five minutes, the church becomes so crowded that there is no room for an apple to fall, and the air becomes hot and stuffy from the thousands of burning candles. A special crush and crush is observed at the iconostasis and near the church walls, where the “pasochniks” have placed the Easter cakes, eggs and all sorts of Easter food brought for consecration.

Church service for Easter

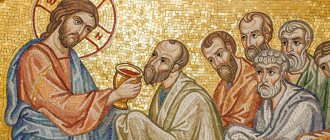

Worship in Orthodox churches begins in the evening of the previous day and continues throughout the night. Although most believers come only in the morning to get to the main part of the action - the Holy Liturgy. In ancient times, it was customary to baptize catechumens on this day. Then, in order to become a Christian, you had to prove your piety over a long period. Such candidates were called catechumens and were not allowed to be present in the church during the celebration of the sacraments.

During Lent, priests wear either passion vestments in red or mourning vestments in purple. In such clothes they begin the Easter service. But as soon as the joyful “Christ is Risen” sounds, they dress in the most beautiful outfits, made of white fabric with an abundance of gold.

Easter is the most beloved holiday among the people

The greatest of Christian holidays, Holy Easter, is at the same time the people’s favorite holiday, when the Russian soul seems to dissolve and soften in the warm rays of Christ’s love, and when people most of all feel a living, heartfelt connection with the great Redeemer of the world. In church language, Holy Easter is called “the triumph of triumphs,” and this name is most consistent with the popular view of this holiday. Even in advance, the Orthodox people begin to prepare for this celebration in order to meet it in a worthy manner, with appropriate splendor and pomp. But the village, where the connection with ancient customs is more vividly felt and where the Orthodox faith stands stronger, is especially active and preparing.

Christening and Easter meal

The special Easter greeting is called Christening. At the end of Matins, after singing: “Let us embrace each other, shouting: brethren! and we will forgive all those who hate us through the resurrection,” believers greet each other, saying: “Christ is risen!” and answering “Truly he is risen!”, they kiss three times and exchange Easter eggs. This is how it is customary to greet each other throughout the 40 days following Easter, until the Ascension.

After the service, believers go to the refectory or home to break their fast. During Holy Saturday and after the Easter service, Easter cakes, Easter cottage cheese, and eggs are blessed in churches. Artos is also blessed at Easter - this is a special leavened bread intended only for prayerful eating. During the service of Saturday of Bright Week, it is distributed to believers to keep at home.

The morning meal after strict Lent was an important moment in the celebration of Easter. On ordinary days, people ate rye bread, vegetables, and cereals, and for the holiday they always baked sweet Easter cakes from white flour, prepared Easter cottage cheese and painted eggs. These dishes were blessed in the temple during the service and brought home.

It was believed that the eggs consecrated in the temple had special miraculous and healing properties. During the meal, the father of the family peeled the first egg, cut it and distributed a piece to each member of the household. Throughout Easter week, eggs were given to relatives, neighbors and acquaintances, guests were treated, and distributed to the poor.

Basically, the festive table differed little from region to region. Easter cakes, Easter cakes, eggs, pies, and meat dishes were placed on it. But in some places, Easter food was very unusual. For example, in Tatarstan, the Kukmor Udmurts considered goose porridge to be their main dish. In addition to this, in the morning the women prepared unleavened flatbread, an omelette baked in the oven, and small balls of steep butter dough, fried in a frying pan and then greased with oil.

The differences in the celebration of Easter in this region are explained by the fact that the Christian holiday coincides in time with the local one - Akashka. It symbolizes the beginning of spring and the agricultural year. According to the Akashka ritual, family members read prayers before meals, sing special drinking songs, visit paternal relatives, and symbolically sow the field. Today this holiday is celebrated not for a week, as before, but for one or two days.

"Pasochniki"

When Matins ends, at exactly 12 o'clock, on the order of the clergyman, cannon or rifles are fired in the fence, everyone present in the church makes the sign of the cross and the first “Christ is Risen” is heard to the sound of the bells. The process of christening begins: the clergyman christens himself in the altar, the parishioners in the church, then the clergyman begins to christen himself with the most respected peasants and exchanges eggs with them. (The latter circumstance is especially highly valued by peasants, since they believe that an egg received from a priest will never spoil and has miraculous powers.)

After the end of the liturgy, all the “pasochniks” with Easter cakes in their hands leave the church and line up in two rows in the fence, waiting for the clergyman, who at that time in the altar sanctifies Easter for the wealthier and more revered parishioners. They wait patiently, with their heads naked; Everyone has candles burning on their Easter cakes, everyone has tablecloths open so that the holy water gets directly onto the Easter cakes. But the clergyman has already blessed the Easter cakes in the altar and, led by the priest, goes outside. The rows of beekeepers began to sway, there was a stampede, a scream, some people had Easter falling out of their bowl, and here and there you could hear the restrained swearing of an angry woman whose Easter cake had been knocked out of her hands. Meanwhile, the clergyman reads a prayer and, going around the rows, sprinkles St. Easter water, for which they throw hryvnias and nickels into his cup. Having blessed the Easter cakes, every householder considers it his duty, without going home, to visit the cemetery and share Christ with his deceased parents. Having bowed at his native graves and kissed the ground, he leaves here a piece of cottage cheese and Easter cake for his parents and only then hurries home to say Christ and break the fast with his household. (Children and their parents kiss Christ three times, and only kissing wives in front of everyone is considered great indecency). To break the fast, mothers always wake up little children: “Get up, little one, get up, God gave us little beads,” and the sleepy, but still satisfied and joyful children sit down at the table, where the father is already cutting Easter into pieces, crumbling the blessed eggs, meat or lamb and feeds everyone. “Glory to Thee, Lord, we had to break our fast,” the peasant family whispers in tenderness, crossing themselves and kissing the consecrated food.

Folk songs

Before the revolution, Easter songs were passed down from generation to generation. With the advent of Soviet power, this tradition almost disappeared in families, but folk ensembles at clubs often knew and sang them.

The main Easter hymn, the troparion “Christ is Risen from the Dead,” was sung during the church service. But in some villages it sounded not only in the temple. For example, in the Smolensk region they performed their own folk version of the troparion. It was called “crying out Christ.” The women who sang it did not spare their voices. “They shouted Christ” in any situation - at work, on the street, during festivities and festive feasts.

In some regions, words from themselves were added to the canonical text of the troparion. They asked God for the main things: health, prosperity, a good harvest. Such songs were sung in the Bezhetsky district of the Tver region. Here, for a long time, the tradition of walking around the village with an icon of the Mother of God on Easter was preserved - the villagers believed that this was how they protected themselves from all sorts of troubles.

In the Pskov region, girls and women sang songs on the first day of Easter, and in the Cossack village of Yaminsky, Volgograd region, wide festivities began later - on the first Sunday after Easter (Krasnaya Gorka), and ended on Trinity. Celebrations here usually began in the afternoon. The Cossacks gathered together on two opposite sides of the farm, set tables and sang songs - “lyuleiki” - as they were called because of the chorus “oh, lyuli, lyuli”. Then we moved to the center of the farm and set a common table on the street.

Games

The celebration of the Holy Resurrection of Christ included not only a solemn service in the church, but also public festivities. After many days of fasting and refusal of entertainment, the celebration took place widely - with round dances, games, and songs. Easter in Rus' was celebrated from 3 to 7 days, and in some regions - even until Trinity (celebrated 50 days after Easter).

A favorite Easter pastime was egg rolling, or “rolling.” Each region has its own rules of the game. For example, in the Pskov region, a player rolled a colored egg down an inclined wooden plank or a steep hill and tried to knock down other eggs standing below. If the participant achieved the goal, then he took the beaten egg for himself and continued the game. If he missed, the next one entered the game, and the unsuccessfully rolled egg remained. Wooden, skillfully painted eggs were often used; sometimes entire sets of such eggs were made especially for this entertainment. Rolling ball is still played in some regions.

Also at Easter they put up carousels and large swings; in the Pskov region they were called “zybki”. It was believed that the future harvest depended on swinging on them. That is why they swayed most often from Easter to Trinity, just during the active growth of wheat. There was also a belief that swings helped to find a husband or wife faster. In the Russian villages of the Udmurt Republic, this belief was preserved in Easter songs and ditties that were sung while swinging: “Red egg! / Tell the groom. / If you don’t say it - / We’ll swing you,” “There’s a swing on the mountain, / I’ll go swing.” / Today I’ll take the summer off, / I’ll get married in the winter,” “Let’s get married, let’s get married, / I’ll get married to myself.”

Swing song “Red Egg” performed by D.P. Dubovtseva and E.M. Barmina from the city of Izhevsk, Udmurt Republic

Among the popular ones was a game known as “toss the eagle” or “toss”. It was most often played for money. The simplest way to play: one of the participants tossed a coin, and when it fell to the ground, the second had to guess without looking which side it fell up. The obverse (heads) always meant a win, the reverse (tails) a loss. That's why the game got its name - "in the eagle." In some villages it has survived to this day, for example in the village of Kadyshevo, Ulyanovsk region.

Spring ritual processions with singing lyrical and round dances...

Pskov region

Easter game of “eagle” in Ulyanovsk Prisurye

Easter swinging and swing songs in Russian...

Dances and round dances

With the end of Lent, the ban on dancing was lifted. An integral part of the Easter festivities were round dances performed to special songs. In the village of Stropitsy, Kursk region, tanks were performed - special round dances of two types: circular and longitudinal. The circles were like a theatrical performance. The dancers sang story songs and played different roles in them. Longitudinal tanks operated on the principle of a stream. These dances were performed only once a year, on Krasnaya Gorka.

File written by Adobe Photoshop? 5.0

In the Bryansk region, round dances were called karagodas. In the first two days of Easter celebrations, they were special: they were attended by men who were reincarnated as elders. To do this, they put on old clothes, tousled their hair, and smeared dirt on their faces. The “elders” stood inside the karagod and danced, while the girls and women “walked to the song” around them. Today, karagodas can be seen at village and school festivals - the round dance tradition is passed on to a new generation.

During Easter festivities in the villages of the Belgorod region they performed a dance with a cross. Its basis was the same round dance, but it was complemented by a cross - a dance in which several people beat out two or three different rhythms with their heels, as if crossing each other. Currently, this dance is performed by folklore groups at rural holidays and festivities.

Traditions of Easter week

For a whole week after Easter, in many villages people walked around their yards and congratulated their owners on the holiday. Volochebniki, that’s what they called those who went from house to house, sang special volocherny songs. It was believed that such a visit would bring good luck and prosperity to the owners, and it was customary to thank them for it with something edible or money. In the Pskov region, owners presented volochebniks with colored eggs, homemade sausage, lard, pies, butter, cheese, and honey. In some villages only women “drag”, in others - only men, and in some there were entire Easter artels of draggers.

In the Kostroma region, on the first Sunday after Easter, newlyweds walked around the yards. This ritual was called “Vyunets”. In the morning, children called out to the newly-made spouses under the windows and sang the song “Young Young Lady.” Boys and girls came to greet the newlyweds in the middle of the day, and adults came in the afternoon. The louse walkers first sang on the porch, then they were invited into the house and treated to food at the table.

The Kukmor Udmurts also had a custom that was reminiscent of traditional Russian circumvention rituals. Young girls and boys riding on festively decorated horses rode into each yard and sang the call “Hurray!” to the owners, calling them out into the street. Later, everyone sat down and the guests were treated to festive food.

"Walking of the Volunteers"

Among the original Easter customs, the meaning of which is dark and unclear for the people, includes, among other things, the so-called “walking of the voles.” This is the same carol, strangely timed to coincide with Easter, with the only difference that the “women” are not guys, but mostly women. They gather in crowds from all over the village and go from house to house, stopping in front of the windows and singing the following song in squeaky, womanish voices:

“It’s not noise that makes noise, it’s not thunder that thunders, Christ is Risen, the Son of God (chorus) The noise is made by the volcanoes - To whose court, to the rich, To the rich - to Nikolaev. Hostess, our father, open the window, look a little, what’s going on in your house (etc.)

The meaning of the song is to beg something from the owner of the house: eggs, lard, money, milk, white bread. And the owners, in most cases, rush to satisfy the requests of the shepherds, since the lively women immediately begin to express not entirely flattering wishes to the stingy owner: “Whoever doesn’t give us eggs will kill the sheep, if he doesn’t give us a piece of lard, he will kill the heifers; They didn’t give us any lard - the cow died.” Superstitious owners are very afraid of such threatening chants, and therefore women never leave from under the windows empty-handed. All collected food and money go to a special women's feast, to which male representatives are not allowed.

Easter signs, superstitions and rituals

As the largest and most revered Christian holiday, Easter naturally groups around itself a whole cycle of folk signs, customs, superstitions and rituals, unknown to the church, but very popular among the village people. The common characteristic feature of all these folk holidays is the same dual faith with which the religious concepts of the Russian common people are still permeated to this day: although the power of the cross defeats the evil spirits, even now this dark force, defeated and cast into the dust, holds timid minds in its power and brings panic to timid souls.

According to the peasants, on Easter night all the demons are unusually angry, so that when the sun sets, men and women are afraid to go out into the yard and onto the street: in every cat, every dog and pig they see a werewolf transformed into an animal. The demons get angry on Easter night because they have a very hard time at this time: as soon as the first bell strikes for Matins, the demons, like pears from a tree, fall from the bell tower to the ground, “and from such a height to fall,” the peasants explain, “That’s also worth something.”

Moreover, as soon as Matins ends, the demons are immediately deprived of their freedom: they are twisted, tied up and even chained, sometimes in the attic, sometimes to the bell tower, sometimes in the yard, sometimes in the corner. Witches, sorcerers, werewolves and other evil spirits find themselves in the same predicament on Easter night. Another group of Easter superstitions reveals to us the peasant’s concepts of the afterlife and the soul.

There is a widespread belief that anyone who dies on Bright Week will freely go to heaven, no matter what sinner he may be. Such easy access to the kingdom of heaven is explained by the fact that on Easter week the gates of heaven are not closed at all and no one guards them. Therefore, the village old men and especially the old women dream of the greatest happiness and ask God to grant them death on Easter week.

At the same time, the belief was deeply rooted among the peasantry that on Easter night one could see and even talk with one’s deceased relatives. To do this, during the religious procession, when all the pilgrims have left the church, you should hide in the temple with a passionate candle so that no one notices. Then the souls of the dead will gather in church to pray and share Christ among themselves, and this is where the opportunity opens up to see their deceased relatives. But you can’t talk to them at this time. There is another place for conversations - the cemetery.

Standing apart from these superstitions is a whole group of Easter signs that can be called economic. Thus, our people are firmly convinced that Easter dishes, consecrated by church prayer, have supernatural significance and have the power to help the Orthodox in difficult and important moments of life.

Therefore, all the bones from the Easter table are carefully preserved: some of them are buried in the ground on arable land in order to protect the fields from hail, and some are kept at home and thrown into the fire during summer thunderstorms to prevent thunderclaps. In the same way, a head of blessed Easter cake is preserved everywhere so that a householder, going to the field to sow, can take it with him and eat it in his field, which ensures an excellent harvest.

But the harvest is also ensured by those grains that stood in front of the images during the Easter prayer service, so a God-fearing householder, inviting the priest “with the gods” into his house, will certainly think of putting buckets of grains and asking the priest to sprinkle them with Holy water.

Along with peasant housewives, women housewives also created their own cycle of omens. So, for example, during the entire Bright Week, every housewife must certainly hide all consecrated food in such a way that not a single mouse can climb onto the Easter table, because if a mouse eats such a consecrated piece, then it will now grow wings and become a bat .

In the same way, during Easter Matins, housewives observe: which cattle at this time lie still - those are the ones that go to the yard, and those that fuss and toss and turn - those that do not go to the yard. During Easter Matins, peasant women have the habit of “shooing” chickens from their roost so that the chickens do not get lazy, but get up earlier and lay more eggs. But perhaps the most interesting is the custom of expelling bedbugs and cockroaches from the hut, which is also timed to coincide with the first day of Easter.

As for the village girls, they too have their own Easter signs. So, for example, on the days of Holy Easter they do not take salt so that their hands do not sweat, they wash themselves with water from a red egg in order to be ruddy, and they stand on an ax to become strong (the ax, they say, helps amazingly, and the girl becomes so strong, that, according to the proverb, “even if you hit her on the road, she doesn’t care”).

Moreover, girls believe that all the usual “love” signs on Easter come true in a particularly true way: if, for example, a girl hurts her elbow, then her boyfriend will certainly remember her; if a cockroach or a fly falls into the cabbage soup, you’ll probably have a date; if your lip itches, you can’t avoid kissing; if your eyebrow starts to itch, you’ll bow to your sweetheart.

Even dashing people - thieves, dishonest card players, etc. - even created peculiar signs dedicated to Easter. Thieves, for example, make every effort to steal something from those praying in church during Easter Matins, and to steal it in such a way that no one would even think of suspecting them. Then feel free to steal for a whole year and no one will catch you.

Players, when going to church, put a coin in their boot under the heel with the firm hope that this measure will bring them a big win. But in order to become an invincible player and be sure to beat everyone and everyone, you need to go to listen to Easter Matins, take cards to the church and commit the following sacrilege: when the priest appears from the altar in bright vestments and says “Christ is Risen” for the first time, the one who came with the cards must answer: “The cards are here.” When the priest says “Christ is Risen” for the second time, the godless gambler replies: “The Whip is here” and for the third time: “The Aces are here.”

This sacrilege, according to the players, can bring countless winnings, but only until the blasphemer repents. Finally, hunters also have their own Easter signs, which boil down to one main requirement: never shed blood on the great days of Bright Week, when all earthly creation, together with people, rejoices at the Resurrection of Christ and glorifies God in their own way.

Violators of this Christian rule are sometimes severely punished by God, and there have been cases when a hunter, having prepared for a hunt, either accidentally killed himself or did not find his way home and disappeared without a trace in the forest, where he was tormented by evil spirits.

Signs

Easter, like any other major holiday, is rich in customs and signs:

- Cool weather, but without frost, means a dry summer, and cold weather means a good harvest.

- If there is thunder and a thunderstorm on Easter, autumn will be dry and late.

- If it is cloudy on a holiday Sunday, it means cold summer.

- A sunny day means a warm and fruitful summer.

- You should not throw away garbage after sunset before Easter - you may lose your luck along with it.

- If crumbs of blessed Easter cake or Easter are fed to the birds, then there will be money all year long.

- If on a festive Sunday a girl’s eyebrows itch, she will soon meet her chosen one and get married.

- If on Easter, after the consecration, you distribute some of the attributes to the poor, your well-being will certainly improve.

- If a woman dreams of having a child, she needs to place an additional plate with Easter cake and a colored egg on the Easter table.

- If a baby is born on Easter, he will be happy, healthy and famous.

- In order to have financial well-being, it is necessary for all family members to go to church for a service, and then immediately return home for the morning holiday meal.

- If you watch the sunrise on Easter, troubles will bypass your home for the whole year.

- In order for the cake to turn out fluffy and tasty when baking, the house should be quiet and calm.

- Broken dishes at Easter mean illness and troubles in the family.

This is only a small part of the signs that have survived and survived to this day.

What not to do on Easter

There are a number of things that are not recommended to do on Easter. Many plans can and should be postponed to other days. Not recommended for Easter:

- work on the land (dacha, garden);

- cut hair;

- go to the bathhouse;

- clean the home;

- remember the dead;

- go to the cemetery;

- have sex;

- sew, wash;

- to be sad, to quarrel;

- swear, gossip;

- hunt for fun;

- get married in a church.

There is no strict prohibition on cleaning the house, but if possible, it is better to refuse all work on this day and devote it to celebrating Easter.

What is possible

Easter is a great holiday and therefore most of the restrictions of fasting lose their force. Those who observed fasting break their fast on this day immediately after the end of the festive service.

The priests recommend doing what brings joy and satisfaction. It is necessary to communicate with loved ones and friends, to share with them the joy of the Risen Christ.

Folk signs associated with the Easter egg

To complete the description of Easter superstitions, customs and signs, it is still necessary to dwell on the group of them that is associated with the Easter egg. Our peasants everywhere do not know the true meaning and symbolic meaning of the red egg and do not even realize that it signifies the world, stained with the blood of Christ and thereby reborn to a new life.

Explaining the origin of this Christian symbol in their own way, the peasants say that the egg was introduced into use by the first apostles: “When Pilate crucified Christ,” they say, “the apostles were very afraid that Pilate would get to them and, in order to soften his heart, They painted the eggs and brought them to him as a gift, as a Jewish leader. Since then, the custom began to paint eggs for Easter.”

In other areas (for example, in the Yaroslavl province), peasants, explaining the origin of the Easter egg, come closer to the truth, although they do not understand everything. “Before Easter,” they say, “Christ was dead, and then resurrected for the benefit of Christians. The egg is exactly the same: it’s dead, but by the way, a living chicken can come out of it.” But when asked why the egg is painted red, the same Yaroslavl men answer: “So Easter itself is red, the Holy Scripture directly says: “a holiday of holidays.” Well, besides that, the Easter bell is also called “red.”

But the peasants answer the question about those signs associated with the Easter egg in incomparably more detail and detail. There will be a whole lot of them. You can’t, for example, eat an egg and throw (let alone spit out) the shell out of the window onto the street, because throughout Bright Week Christ himself with the apostles, in beggar’s rags, walks on the ground and, if you are careless, you can get hit by the shell (he does walk Christ, in order to observe whether the Orthodox are fulfilling his covenant well - to provide for the poor brethren, and rewards the greedy and generous, and punishes the stingy and unmerciful).

Then, peasants everywhere believe that with the help of an Easter egg, the souls of the dead can find relief in the next world. To do this, you just need to go to the cemetery, christen the deceased three times and, having laid an egg on his grave, then break it, crumble it and feed it to a “free” bird, which, in gratitude for this, will remember the dead and ask God for them. With the help of an Easter egg, the living get relief from all diseases and misfortunes. If the egg received at the time of Christhood from the priest is kept in the shrine for three or even 12 years, then just give such an egg to the seriously ill to eat, and all the illness will be removed from them as if by hand.

The egg also helps in extinguishing fires: if a person distinguished by a righteous life takes such an egg and runs around the burning building three times with the words: “Christ is Risen,” then the fire will immediately subside and then stop on its own. But if the egg falls into the hands of a person of a dubious lifestyle, then the fire will in no way stop, and then there is only one remedy: throw the egg in the direction opposite to the direction of the wind and free from buildings - then the wind will subside, change direction and the strength of the fire will weaken so much that that it will be possible to fight him.

But the Easter egg helps most of all in agricultural work: you just have to bury such an egg in the grains during the Easter prayer service and then go with the same egg and grain to sow in order to ensure a wonderful harvest. Finally, the egg even helps treasure hunters, because every treasure, as you know, is guarded by an evil spirit specially assigned to it, and when they see a person approaching with an Easter egg, the demons will certainly get scared and scatter, leaving the treasure without any protection or cover - then just take a shovel and calmly tear off your cauldrons of gold.

Second day of Easter

The walk with the icons continues in all courtyards until the evening of the first day of St. Easter. And on the second day, after the liturgy, which ends very early, the icons are carried to the “popovka” (the place where the clergy houses are located) and after a prayer service in the priest’s house, the peasants receive refreshments from their spiritual father. It goes without saying that in such cases the whole village gathers for the “popovka”. “There’s a noise all over the street,” says one of our correspondents, describing this kind of celebration, “some are thanking, and some are cursing, remaining dissatisfied with the small or bad treat: “If he comes to us, that means he’ll come,” voices are heard from Father’s address - he drinks, eats as much as he wants, he won’t go into his entrails, but when you come to him, he’ll bring you a glass, and go with God.” “However,” the correspondent adds, “there are always very few dissatisfied, since the priests do not skimp on treats, valuing the location of the parishioners and wanting, in turn, to thank them for their cordiality and hospitality.”

From the “priest”, the icons go to nearby and distant villages, going around the entire parish, and each village is warned in advance when the “gods will come” to it, so that the peasants have time to prepare. To complete the description of Easter prayers, it is also necessary to mention that at night the icons are brought for storage either to a school, or to the house of some wealthy and respected peasant, who usually asks for this honor himself and asks the priest: “Father, release the Mother of God to me.” spend the night." It often happens that at night, in the room where the icons are kept, parishioners organize something like an all-night vigil on their own: old women from all over the village, pious men and women begging for good suitors, gather here and light candles, sing prayers and kneel in prayer to God . In the past, so-called “kanunnichki” (small jugs of honey) were brought here, which were placed in front of the images on the table to commemorate the dead. “Kanunnichki”, in all likelihood, is the invention of schismatics (Old Believers - editor's note), who in the past willingly brought their own jugs to the images and stood in prayer with the Orthodox all night. But now “kanunnichki” are strictly prohibited by the highest spiritual authorities and have fallen out of use everywhere.

Where did the tradition of dyeing eggs come from?

The tradition of giving each other colored eggs on the day of the Resurrection of Christ spread thanks to Mary Magdalene. Mary was the first to whom Christ appeared after his Resurrection and said: “Do not touch Me, for I have not yet ascended to My Father; But go to My brothers and say to them, “I am ascending to My Father” (John 20:17). Mary Magdalene brought the good news to the Apostles that she had seen the Lord. This was the first sermon about the Resurrection.

When the Apostles dispersed from Jerusalem to preach to all corners of the world, Mary Magdalene also left with them. Even before the Apostle Paul, a woman went to Rome, the center of the then civilization. The brave disciple of Christ even appeared to Emperor Tiberius and told about the life, miracles and teachings of Christ, about how He was slandered by the Jews and crucified by the verdict of Pontius Pilate.

The Emperor doubted the story of the Miracle. Then Mary Magdalene took a white egg, which she brought to the palace as a gift, and with the words “Christ is Risen!” gave it to Tiberius. Before the eyes of the Roman ruler, the egg turned from white to bright red.

In the library of the monastery of St. Anastasia the Patternmaker, located in the northern part of Greece, near the city of Thessaloniki, a handwritten Greek charter of the 10th century has been preserved. It contains a prayer read on Easter Day for the blessing of eggs and cheese. The abbot, distributing the consecrated eggs, says to the brethren:

So we accepted from the holy fathers, who preserved this custom from the very times of the apostles, for the holy Equal-to-the-Apostles Mary Magdalene was the first to show the believers an example of this joyful sacrifice.

Celebrating Easter among the Slavs

The first Passover was celebrated by the ancient Jews 1500 BC. uh, escaping Egyptian slavery. The New Testament, Christian Easter was established by the apostles after the resurrection of Jesus. By the 5th century The Orthodox Church has developed its own rules and timing for celebrating the Resurrection of Christ. The Orthodox Slavs celebrated Easter with many customs, rituals, and traditions that have been preserved since pagan times.

Easter cake was never known in the Old Testament Easter, and indeed in Christianity in general. The Passover lamb was eaten with unleavened cakes (unleavened bread) and bitter herbs. The origin of Easter cake is pagan. Kulich, like tall bread with eggs, is a well-known pagan symbol of the god of fruiting, Thalossus. The Russian people, as coming from paganism, still interfere with the concept in folk etymology.

Slavic-Aryan Paschet

In most of the myths of ancient peoples, there were dying and resurrecting Gods. So, in early spring, the Egyptians greeted each other with the words: “Osiris has risen!”

The Slavs did not invent resurrection gods for themselves, but they did have a holiday, surprisingly reminiscent of Easter in its name. The oldest source on the history of the Slavs, the Vedas, reports that in the first centuries of our era, Slavic tribes celebrated a special holiday called “Paskhet,” which roughly meant “Path of Deliverance.” What kind of deliverance was meant? Easter was dedicated to the completion of the 15-year march of the Slavic-Aryan peoples from Daaria - the land considered the ancestral home of our ancestors. The legend said that evil creatures settled on the earth - koshchei, killing people. But one of the main deities of the Slavs, Dazhdbog, did not allow the “dark Forces from the Pekelny World” to be defeated, which were gathered by the Koschei on the nearest Moon-Lele (in those days the earth had 3 Moons: Lelya, Fata and Month). He destroyed the Moon with magical powers, a fiery rain began, and after it the Great Flood. Daaria plunged into the ocean, thousands of people died, but many managed to escape. The legend is surprisingly reminiscent of the Biblical Flood and the exodus of Moses from Egypt, isn’t it? By the way, a well-known ritual appeared to all of us in memory of this event. On the eve of Easter, which was celebrated in early spring, the Slavs painted eggs with ocher and beat them against each other. Broken eggs were considered a symbol of hell, or Koshchei, and unbroken eggs were considered a symbol of the victorious force of evil, Dazhdbog. The eggs were painted bright colors to remind of the fiery rain from the sky after the destruction of the Koshchei. In the celebration of Easter one can easily see the roots of the celebration of the later Christian Easter.

Ancient rituals and Easter symbols

On April 16, the ancient Slavs solemnly celebrated the end of the great wedding of heaven and earth, the readiness of the earth for fertility and sowing. Women baked cylindrical-shaped babkas as a symbol of masculinity, painted eggs as a symbol of masculine power, and made round curd dishes as a symbol of femininity.

The Slavs, long before the adoption of Christianity, had a widespread myth about how a duck’s egg became the embryo of the whole world. “At first, when there was nothing in the myrtle but the boundless sea, a duck, flying over it, dropped an egg into the watery abyss. The egg split, and from its lower part the damp mother earth emerged, and from the upper part arose the high vault of heaven.” Let us remember that the egg contained the death of Koshchei, from which all the evil in the Universe came. There are other customs associated with the egg. So, our ancestors wrote magical spells and prayers on bird eggs, brought them to pagan temples, and laid them at the feet of idols. The Eastern Slavs dedicated painted eggs to the most formidable deity, Perun. In the first Slavic cities (this custom is little known in villages), lovers gave each other colored eggs in the spring as a sign of sympathy. The ancient Slavs were pagans, like the vast majority of peoples in the world. Religions that have long sunk into oblivion were based on faith in forces beyond the understanding of people. Actually, Christianity is based on the same worldview.

The Christian faith, like pagan beliefs, is based on humanity’s most ancient ideas about the afterlife, about life after death. The ancient Slavs, long before the advent of Christianity, viewed the world as a struggle between two principles - good and bad; Christianity, for its part, adopted these views and strengthened them.

The main Easter symbols - streams, fire, Easter cakes, eggs and hares - have roots in the distant past. , the spring water of the stream was necessary for cleansing after illnesses and all kinds of misfortunes. Maundy Thursday seemed to embody the ancient beliefs of peoples. The Easter fire is the embodiment of the especially revered fire of the hearth. Ancient people revered fire as their own father; it gave them warmth and tasty food, protection from predatory animals. On the ancient holiday of Easter, fires were lit everywhere, and firewood burned brightly in the hearths. Fire had a magical effect on people and had cleansing powers. European tribes lit numerous fires at the beginning of spring to drive away winter and welcome spring with dignity. The Church made fire a symbol of the Resurrection. Already at the very beginning of the spread of Christianity in the 4th century. The custom arose of placing a candle at the altar during the night Easter service - the sacred flame symbolized the Resurrection of the Savior. Throughout the Middle Ages, believers adhered to the custom of taking burning candles home from church in order to light lamps or a fire in the hearth.

Easter cakes, colored eggs, hares and bunnies are also not a Christian discovery. It has already been said that the prototypes of Easter cakes - babka - have been baked by Slavic women in the spring since time immemorial, and hares have always been considered a symbol of fertility among many peoples. The prototypes of colored eggs were also borrowed from ancient tribes as a symbol of new life, as a small miracle of birth.

Pagan gods and Orthodox saints

Prince Vladimir I in the middle of the 10th century. carried out a kind of reform of the pagan gods in order to strengthen his power. Next to his mansion, on a hill, he ordered to place wooden idols depicting Perun, Dazhdbog, Stribog, Semargl and Mokosh.

At the same time, Christianity was already known in Rus' (the first information arrived in Rus' in the second half of the 9th century). Wanting to expand his power to Byzantium, Vladimir decided to baptize Rus'. In 988, the prince first baptized himself, then baptized his boyars and, under pain of punishment, forced all Kyivans and residents of other Russian cities and villages to accept the new faith. This is how the history of Christianity in Rus' began. The Russians gradually stopped burning their dead on funeral pyres, every year they sacrificed less and less sheep to the wooden idols of Perun, and completely stopped making bloody human sacrifices to idols. But at the same time, they continued to celebrate their traditional holidays, baked pancakes for Maslenitsa, burned bonfires on Ivan Kupala Day, and venerated sacred stones. A long process of merging Christianity with paganism began, which has not yet been fully completed in our time.

The Christian Church was unable to turn people away from their usual holidays and rituals. Documents have been preserved in which priests complain that people prefer pagan amusements and gatherings to visiting church. A church procession could encounter a crowd of masked “mermaids” and “ghouls” on the city streets. Horse races, tournaments, and games were held near the cathedrals. Then the priests acted differently: they tried to replace the old pagan holidays with new, Christian ones. The oldest Slavic winter holiday was dedicated by the church to the Nativity of Christ, and few people know that the ringing of bells was also borrowed from the pagans. Many centuries ago, on the coldest days, the Slavs tried to make a lot of noise, hitting metal objects in order to revive the life-giving rays of the sun. Later, on all major Christian holidays, bells began to ring in churches, but for a different purpose - as a greeting to Christ. Old traditions have left their mark on the celebration of Christian Christmas: the singing of carols and pagan songs, masquerades, and Christmas fortune-telling have become traditional.

The Orthodox Mother of God outwardly resembled the pagan goddess of earth and fertility Lada - the mother of the Gods, the eldest Rozhanitsa, and later Bereginya, thereby uniting the old and new religious cults. Among the many gods, the ancient Slavs especially revered Volos, or Peles, who, according to mythology, was “responsible” for the afterlife, for the fertility of livestock and the well-being of forest inhabitants. His companion was a cat. After the adoption of Christianity, the church for a long time tried to prohibit the veneration of both Peles and his cat, but every year at the end of May, festivities dedicated to this ancient God were held in many villages. The church had to find a “replacement” - May 22 was declared St. Nicholas Day. Like all agricultural peoples, the Slavs were constantly concerned about the future harvest and tried to do everything to make the year successful. In early May, with the appearance of spring seedlings, another spring holiday was celebrated - the day of the god Yarila. The day of the sun was celebrated, which later grew into the Christian holiday of Trinity. On this day, the Slavs decorated trees with ribbons and houses with tree branches. The summer solstice was crowned by another pagan holiday - Ivan Kupala, now celebrated as the Nativity of John the Baptist. Bright lights in churches during holidays and services are also an ancient custom that existed in Rus' long before the adoption of Christianity. At all pagan holidays, both winter and summer, the Slavs lit bonfires, lit torches, and made torchlight processions to the temples. Fire drove out evil forces, winter cold, and in summer - all kinds of evil spirits. In the Christian church the meaning of fire has changed; it is considered an additional symbol of Jesus' importance as the Light of the World.

Easter holidays and paganism

During pagan holidays, many ancient tribes decorated trees in winter. Christianity, represented by the monk Saint Boniface, made the spruce its sacred symbol. Trying to lure the Druids to the Christian faith, Boniface claimed in his sermons that the oak tree, sacred to the Druids, managed, by falling, to destroy all the trees except spruce. Therefore, Christianity declared not the oak, but the spruce as a sacred tree. After the pagan Christmastide (transformed by Christianity into Christmas) and the spring festival of Maslenitsa, a new significant period for the Slavs began. Village residents gathered for prayer addressed to Beregina. The women stood in a round dance, one of the participants held bread in one hand and a red egg in the other, which symbolized the vital energy that the sun gave to people and all living things. In ancient times, eggs were painted only red - this was the color of fire, revered by all tribes. In addition, among the Russians, the color red was the personification of beauty; Christian priests timed the holiday of Great Easter to coincide with this time. At the same time, the Red Hill holiday was also celebrated. The Slavs gathered on the hills and slides and welcomed spring. Many ancient peoples had their own sacred mountains, hills and steep slopes, on which bonfires were lit, sacred rites and prayers were held. One of the ancient covenants addressed to the newlyweds sounded like this: “Vyu, asshole, give back our eggs!” In response, the young people presented those present with colored eggs, Easter cakes, and gave them beer and wine. On Red Hill, red eggs were rolled on the graves of relatives, later distributing them to the poor. Krasnaya Gorka was considered in Rus' the most suitable time for weddings (the second such period came after the harvest).

In early spring, when the ground was cleared of snow and the fields were ready to receive seeds, ancient man performed rituals dedicated to his ancestors, who also lay in the ground. Peasants in families went to cemeteries and brought ritual funeral dishes to the “grandfathers”: kutya made from millet porridge with honey, chicken eggs. By appeasing their deceased ancestors, people seemed to ask them to help the future harvest. The Slavs called these days Radunitsa (from the word “to rejoice”). People, remembering the dead, believed that they were enjoying the spring and the sun with them. Red-painted eggs were a symbol of the connection between the dead and the living; some people even buried the eggs in small holes next to the grave. This custom was found among the Greeks and Romans in the pre-Christian period, when colored eggs were left on the graves of relatives as a special gift to the dead. Brides and grooms also left colored eggs on the graves of relatives, thus asking them for blessings for marriage. Remembering their relatives, they drank a lot of wine and beer, which is where the saying even came from; “We drank beer about Shrovetide, and had a hangover after Shrovetide.”

In the northern Russian provinces, people walked on Radunitsa, singing, under the windows of their neighbors, songs that resembled Christmas carols, sounded differently in each province, but everywhere in the same way, in response to them, the singers were presented with colored eggs, gingerbread, wine and pancakes.

On July 20, the ancient Slavs especially revered the thunder god Perun, while the Christian religion declared this day Elijah's day. It was one of the darkest days of the whole year - no songs were sung, no people even spoke loudly. Perun demanded bloody sacrifices and was considered a formidable deity, as did his Christian successor later. And although the people began to call July 20 Elijah’s Day, pagan traditions were preserved for a long time: peasants collected “thunder arrows” that did not hit the devil and remained on the ground; they did not allow cats or dogs into the house on this day, since there was a fear that God can incarnate in these animals. And the priests had to announce, in accordance with the ancient traditions of the people, that on Elijah’s day it was impossible to work in the field.

Easter after Nikon's reforms

Before the reforms of Patriarch Nikon, Easter looked more like a great pagan festival than a celebration of Christ's victory over death. During Holy Week, Monday was considered a men's day, guys doused girls with water, and it was believed that if a girl remained dry, she was not beautiful and good enough for suitors. On Tuesday, the girls took revenge on the guys by dousing them in retaliation - it was women's day. On Wednesday and Thursday, the whole family carefully cleaned the house and outbuildings, put things in order, and threw out old trash. Maundy Thursday was also called clean, because on this day, according to ancient pagan traditions, one should swim in a river, lake or bathhouse at dawn. Christian traditions adopted these rituals, and on every “Clean” Thursday, all believers not only washed in baths and ponds, but also cleaned all living and courtyard areas. In the northern regions of Rus', they collected juniper or fir branches, burned them, and used smoke to fumigate their homes, barns, and stables. It was believed that juniper smoke was a talisman against evil spirits and diseases. On Friday it was impossible to do anything except the most necessary things. On this day, eggs were painted and dough was placed on Easter cakes, and married women delivered food for the Easter table to poor houses. On Saturday, services continued all day, Easter cakes, colored eggs and Easter were blessed in churches. The common people, in addition to the fires, lit tar barrels, the boys placed torches and bowls with burning oil everywhere. The bravest ones placed lanterns on the dome of the church. The remaining coals from the fires were then stored under the eaves of the roof to prevent a fire.

During the Holy Week following Easter, believers sang songs and went home in crowds. They called this crowd a bully, and its leader - a leader. The first song was addressed to the owner and mistress, it glorified the construction of the house, wealth, and piety. It was also mentioned that Saint George protects cows, Saint Nicholas protects horses, Saint Ilya protects the fields, the Most Pure Mother sows, and the Intercession reaps the harvest. After each line, the chorus was certainly sung: “Christ is Risen.” These songs had deep pagan roots; they were performed back in the days when no one knew about Christianity. Farmers in their songs expressed concern about the future harvest and were worried about the safety of their livestock. In the Polish lands, the Slavs carried a live rooster with them during the procession, which was seen as a symbol of the resurrection.

All week long, bonfires burned in high places as a symbol of the victory of spring over winter. Priests walked around the courtyards with icons, accompanied by the so-called God-bearers (usually pious old women and men). God-bearers carried candles with them to sell and mugs to collect donations for the construction of churches. The priest's retinue certainly dressed in festive clothes and girded with white towels, and elderly women tied their heads with white scarves. First, everyone gathered at the church, the priest blessed the Easter cakes with burning candles and made a religious procession around the temple. After this, the Easter procession began through houses and courtyards. The start of the move was announced by the ringing of a bell. The hosts were waiting for the guests - they lit candles near the icons, covered the table with a new white tablecloth and placed a round rug and two loaves of bread on it, and hid “Thursday” salt under one of the corners of the tablecloth. The host, without a headdress, greeted the dear guests and, while the prayer service was going on, stood in front of the priest and his retinue. At the same time, the woman was holding in her hands the icon of the Mother of God. The men quietly counted out loud how many times the priest would say the words: “Jesus, son of God.” This was done less than twelve times; they asked in chorus to repeat the prayer service. In the courtyards, a prayer service was served separately for the cattle. The tables were set and “Easter Easter” cakes were placed on them. After the prayer service, the Easter cakes were divided into pieces and fed to livestock so that they would be healthy and fertile throughout the year. The priest, upon special request, could bless the water in the well. In some villages, during this ritual, men took off their nail crosses and blessed them in water, while nursing women washed their breasts with holy water, and sick children were sprinkled so that they would recover.

Source

How is Easter celebrated today?

At all times, right up to the end of the first quarter of the 20th century, Easter remained not only the main spring holiday, but also the most central event in the calendar. This was the case until the early twenties, when atheism became government policy. The authorities banned Easter liturgies, contrasting the Resurrection of Christ with its counterpart - Workers' Solidarity Day.

But already in the early nineties of the last century, all prohibitions were lifted and several red days in the spring again appeared on the calendar. As in the old days, Easter occupies a dominant place among all religious events. Even the head of state attends a service on this day in the Cathedral of Christ the Savior in Moscow.