What are the main approaches to organizing volunteer activities within the framework of social service and diaconal practices of modern Orthodoxy? This was discussed at the next scientific seminar of the Center for Research of Civil Society and the Non-Profit Sector (CIGOiNS) of the National Research University Higher School of Economics, held under the leadership of the first vice-rector of the National Research University Higher School of Economics, scientific director of the Center for Civil Society and Non-Profit Sector Studies (CIGOiNS) Professor Lev Yakobson.

The speaker, Associate Professor of the Faculty of Humanities at the National Research University Higher School of Economics, Candidate of Philosophy Boris Knorre, focused the audience’s attention on the main types of religious volunteer associations, charitable organizations and parent church structures that actively attract volunteers to their activities. It was also noted that in the Russian Orthodox Church itself there is a process of institutionalization and analytical understanding of social service.

Analyzing the mechanisms for attracting volunteers and the peculiarities of their motivation, Boris Knorre identifies (with a certain degree of convention) two main models of organizing Orthodox communities and social groups: authoritarian-mystical and socially open. The emergence of the latter model shows the dynamics of changes in religiosity and sociocultural priorities in modern Orthodoxy. The analysis is based on empirical data obtained through interviews with parish priests and organizers of church diaconal initiatives over a number of years.

Various types of help needed

Since the involvement of volunteers in the social activities of the Russian Orthodox Church is mainly associated with the development of social service in the church, the speaker recalled the main steps of the church leadership, aimed 7-8 years ago at making Orthodox social service more systematic, comprehensive and integral from the church- parish life. He also drew special attention to the fact that the Department for Church Charity and Social Service of the Russian Orthodox Church (hereinafter referred to as OCBSS) formed a special Database of Social Service, which began to monitor Orthodox social service by dioceses. The database partially covers even some church social services organized in foreign dioceses, but the main body of data (95%) relates to Russia.

The speaker presented a table compiled on the basis of the Database, which listed various types of assistance provided by church social centers and services. Such assistance today is quite varied: it can be medical, rehabilitation, social, psychological, counseling, spiritual, but at least half of the types of assistance provided by church social services are aimed at satisfying minimal material needs and making up for the lack of well-being among socially vulnerable categories of the population. For example, 1018 organizations are involved in the distribution of clothing aid, and 967 organizations are involved in the supply of food. Volunteers are mainly involved in the implementation of this type of assistance. In addition, there are volunteers in centers that supply people with clothing, medicine, food and help replenish the resources they lack for their lives (this also includes assistance in arranging overnight accommodation, purchasing tickets to their place of residence for people in distress, assistance with home, including repairs and home improvement, transport assistance).

In total, today in Russian dioceses social assistance is provided by 4,302 church social services and organizations, more than 90% of them are organized at churches and monasteries. Organizers of church social services, who have accumulated relevant experience, publish special manuals on long-term rehabilitation of categories of socially excluded citizens.

Among the weaknesses of this systematization process, according to the speaker, is the inability to administer all kinds of social services, since they sometimes arise spontaneously, at the behest of the hearts of enthusiasts, and accordingly, helping one’s neighbor cannot be fully integrated into any centralized and regulated system. As noted in the study by Zabaeva I.V., Oreshina D.A., Prutskova E.V. “Specifics of social work in the parishes of the Russian Orthodox Church: the problem of conceptualization”, informal, non-professional social activity “does not lend itself well to recording and presentation in reporting documents”, accordingly, “church social life may become skewed towards types of activities that fit within the framework of formal reporting. As a consequence, the most simple, productive and, apparently, the most profitable level of non-specialized social work may turn out to be undervalued and uncultivated in parishes.”

Nevertheless, according to the speaker, the Russian Orthodox Church has some success in this field. Church social activities have become more systematic; we can talk about its institutionalization and widespread volunteer participation in social service.

Volunteers in the Orthodox Diaconate: Encouraged Volunteering and Monastically Oriented Rules

According to Boris Knorre, volunteering is integral to social service, because the social activities of the church to one degree or another imply a moment of sacrifice and charity. Even those employees of social centers who receive payment for their work can still act as volunteers to some extent, since this payment is usually lower than that required in the corresponding secular organizations. But in general, the activities of church social centers are based on the work of enthusiasts who help suffering people absolutely free of charge.

Knorre notes that over the years of research on this topic, he has encountered different attitudes towards the concept of volunteering in the church. There is even a negative attitude towards the word volunteer. Those who take this position explain their attitude by saying that, in general, service to one’s neighbor in Christianity cannot be a subject of personal arbitrary choice, but must be determined by a unique ethics of duty, remembering that helping one’s neighbor is the duty of a Christian, and no one has the right to evade this duty .

In addition, the speaker noted that there are church social centers, both parish and monastic, where priest-leaders insist that not only the decision to serve one’s neighbor, but also the choice of the type of social service itself should be determined by the priest, and not by the volunteer. The priest offers to perform this or that service as an act of obedience. And an enthusiast who has come with the initiative to show himself in a specific diaconal practice may encounter mistrust or even some doubt on the part of the priest. The latter may invite the potential volunteer to undertake a completely different type of activity than he would like to offer.

Examples when a person is offered to help not out of his own whim, but also due to certain values, the internal culture of organizations, ethical requirements, are actually integrated into a broader phenomenon - “incentivized volunteering”

The speaker gave examples of interviews obtained during the study of the topic in 2015–2017. Among the illustrative examples of a distrustful attitude towards volunteering was a situation told by a nun working in one of the social church centers in Kaluga, who was transferred there against her will from a provincial rural monastery. She said that she provided various assistance to lonely old people living next to this monastery, but at some point they decided against her will to transfer the nun to a large urban center (in church language, they gave her a special “obedience”). At first this shocked her, but at some point the nun not only felt natural in the new place, but also became convinced that priority should be given “not to the work to which your soul lies, but to the one for which you will be blessed.” and do the latter as obedience.”

As the speaker said, this position is not excluded, however, for the laity. For example, the chairman of the Synodal Department for Church Charity and Social Service, Bishop Panteleimon (States), while still a “white” priest named Fr. Arkady, addressing the sisters of mercy from the St. Demetrius sisterhood, expressed the point of view that works of mercy should be devoid of any admixture of personal passions, for example, “passion for novelty.” He noted that people who strive to help on impulse, following only their own spiritual impulses inevitably cool down when a person is faced with reality, and not with the picture that he imagined.

In his meetings and publications devoted to the burnout syndrome that occurs among the “sisters of mercy,” Shatov noted that the loss of inspiration and enthusiasm should even be perceived as a necessary and somewhat normative stage on a person’s spiritual path, since it helps to overcome sin and passionate nature of man. Father Arkady emphasized the importance of “obedience” and “blessing,” saying that “it is very important to learn such obedience in order to do not in your own way, not according to your own desire, but to do as you will be blessed.”

At the same time, we note that it was Shatov, despite the many psychological problems that arose among his wards, who managed to create a completely unique and very effective comprehensive social service service “Mercy”, which today allows for a diverse experience in organizing social service with the active involvement of volunteers.

Boris Knorre nevertheless believes that these examples clearly characterize a paradigm that can be called authoritarian-mystical. It allows us to explain those authoritarian principles that are characteristic of individual church communities when organizing the provision of social assistance and are based on the monastically understood principles of obedience and renunciation of one’s will. According to the speaker, the principles he illustrated, of course, do not fully reproduce the monastic ascetic model, but only demonstrate cultural attitudes arising from monastic experience and which received their local reception in the Russian church tradition in particular.

It must be admitted that the speaker was not clear in his assessment of the authoritarian-mystical model of organizing volunteer groups. He cited as a “Pro” argument the study of Western scientists Agata Ladikovskaya and Detelina Tocheva, “Women teachers of religion in Russia: gendered authority in the Orthodox Church,” published in Archives de Sciences Sociales des Religions, 162, 2013, pp. 55–74. According to him, researchers convincingly show that the principles of obedience, submission, strict authoritarian subordination and control by clergy, traditional for patriarchal hierarchical cultures, do not always work unambiguously to limit human self-realization. The authors cite the example of Orthodox women teachers who, thanks to the blessing of the clergy, receive “new breath” in their profession. Accepting the system of church ethos, including in the form of that same authoritarian-mystical paradigm, they do not feel at all any suppression or discrimination, but on the contrary, in the person of the priests who bless them, they feel additional strength, empowerment in terms of defending their ideological and professional principles in secular education and even in academic science.

The presenter of the seminar, first vice-rector of the National Research University Higher School of Economics, scientific director of the Center for Research on Civil Society and the Non-Profit Sector of the National Research University Higher School of Economics Lev Yakobson gave his assessment of the presented model. He noted that the examples given, when a person is offered to help not out of his own whim, but also due to certain values, the internal culture of organizations, and ethical requirements, are actually integrated into a broader phenomenon - “incentivized volunteering.” It doesn't exist only in the church. For example, parallels can be drawn with volunteering in educational institutions. According to him, Soviet practice provides vivid examples of incentivized volunteerism, and those who lived at that time understand that this was real volunteerism. There's a lot to explore here and it's interesting.

Lev Yakobson’s idea was supported by Daria Dubovka, an analyst at the Center for Basic Research at the National Research University Higher School of Economics. She cited as an example of incentivized volunteering the activities of volunteers from the All-Russian Society for the Protection of Historical and Cultural Monuments (VOOPiK), which operated during the last 25 years of Soviet power. In her opinion, some of the principles that guided the VOOPiK volunteers were similar to the principles voiced by the speaker.

The example of the St. Demetrius sisterhood, which the speaker gave in his speech, however, caused a discussion at the seminar. The editor-in-chief of the Internet portal “Miloserdie.ru” Yulia Danilova spoke out in favor of the fact that it is not very legitimate to classify the sisters of mercy from the St. Demetrius Sisterhood as volunteers, since this is a completely special category, with a very special type of behavior. “If they are classified as volunteers, then this is a very specific category of volunteers, close to monastic service.” As it turned out, sisters of mercy even take special vows. According to Danilova, the activities of the sisterhood deserve more detailed scientific study.

In the field of church social ministry today there is definitely a much greater difference in approaches to organizing volunteer activities than before

Speaking at the seminar, the head of the volunteer movement “Danilovtsy” Yuri Belanovsky (the Movement was created 8.5 years ago as one of the projects of the Patriarchal Center for the Spiritual Development of Children and Youth at the Danilov Monastery) noted that during his numerous trips to Russian regions he makes in order to exchange experience, he is very often asked to help organize volunteer groups precisely according to the “obedience volunteering” model. This model is seen by many as attractive from the point of view of its apparent simplicity - with its help, the organizers hope to quickly direct human resources to the implementation of specific tasks. At the same time, in reality it turns out that this model works much worse, and we have to move away from “obedience” and be guided by completely different principles, based on a person’s individual choice. According to the leader of the Danilovites, this leads to a kind of duality, when the ideal is retained by the ascetic model of “volunteering by obedience,” but in practice one has to choose a socially oriented model in order for something to actually be done.

How to pass a test without a C

In our free time from singing, we are ordinary volunteers. For me, volunteering is a tool on the path to God. It is very important not to perceive this as a “party” and then the Lord will help in other matters. When the relics of St. Nicholas were brought, we were also volunteers (part of the relics of St. Nicholas the Wonderworker from the Italian city of Bari was in Moscow from May 21 to July 13, 2017 - Ed).

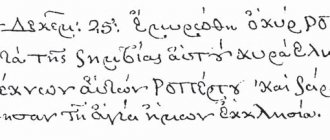

To the relics of St. Nicholas. Photo of the priest. Igor Palkin

My task was to organize the choirs so that they would sing five prayers a day for a month and a half in a row. It was quite difficult: I was in the Cathedral of Christ the Savior almost from morning to night and at the same time I was taking a test at MEPhI.

Therefore, not everything turned out as well as we would like. Despite being completely busy at the temple, this was the only time during the summer session that I did not receive a single “C”.

Photo from Anna Golik’s archive and from the Orthodox Volunteers website.

Volunteering in a socially open model

Having finished the conversation about church social centers of the mystical-authoritarian model, the speaker noted that today this model, however, is by no means the only one. Moreover, some volunteer Orthodox organizations even criticize it. In this regard, the speaker cited the words of Yuri Belanovsky: “A volunteer and a volunteer, based on the very definition of this word, is a person who undertakes to help others of his own free will, of his own free will, and not because of anyone’s instructions and manipulations. Unfortunately, in some church parishes a person is often encouraged to engage in social work contrary to his inner motivation. He can be manipulated, he can be put under psychological pressure, including by speculating that he must fulfill obedience.”

According to Belanovsky, the latter case is a substitution, a kind of surrogate for volunteering.

As Knorre further noted, during the second half of the period of the post-Soviet revival of Orthodoxy in Russia, self-reflection about subcultural traditions, church ethics and ascetic monastic principles became characteristic of many Orthodox believers. Parishes began to focus more on social openness, on giving a greater share of responsibility to parishioners (although this share greatly depends on the diocese and on the parish).

By the same logic, church centers organizing social service began to rebuild the principles of organizing volunteers and offering more complex motivation for their involvement in works of mercy. The speaker cited the following characteristic statements of priests: “Young people today cannot be attracted to social activities by talking about obedience and cutting off their will. By doing good deeds, volunteers must realize themselves, justifying their ideas about life and internal ideals” (Priest Alexey Alekseev, Vysoko-Petrovsky Monastery).

“As volunteers on whom you can rely, only adults with established principles should be involved in works of mercy, and if young people are involved, then not so much for works of mercy, but in order to provide an opportunity for personal search and self-determination for the youth themselves.” (Front Alexander Sandyrev, Chairman of the Youth Department of the Ekaterinburg Diocese)

“Volunteers are not only altruists, they work to gain experience, special skills and knowledge, and establish personal contacts.” (Volunteering - general issues. Published by the Synodal Youth Department of the Russian Orthodox Church. Tver, 2014).

That is, from this point of view, volunteering is perceived as a kind of springboard for the possibility of self-realization or even choosing a life path, and not at all as a path of monastically understood obedience. Obviously, there can be no talk of authoritarian-mystical principles here. The model of organizing church social service, presented in the examples given, can be characterized as a model of a socially open type, because it allows volunteers to more individually and freely choose the type of social service. Thus, using specific examples, we can see a radically different approach to volunteering.

In addition, Knorre noted that changes towards a socially open approach can also take place within the same church structure, in particular, this is happening in the above-mentioned “Mercy” service, whose employees demonstrate sufficient flexibility and variability. In the field of church social ministry today there is certainly a much greater difference in approaches to organizing volunteer activities than before.

Gift from God

We regularly sing at services in one pre-trial detention center (pretrial detention center). When you are in his home temple, even after passing all the necessary checks, it is difficult to understand that you are in prison. I remember we were talking with a girl with whom we had just completed our service. Everything is so easy, we even joke with her, we smile and it feels like this is my old friend whom we unexpectedly met and decided to chat with. After this conversation, a friend told me that the day before this girl had a trial and was given nine and a half years. She is now 17 years old, and she will only be released at 26. It is impossible to understand this. Temple, services, church sacraments - all this changes people, the atmosphere between us all. This is even noticeable in the faces of the prisoners before and after the service - they are completely different. They leave the temple more joyful and bright. In general, the temple in the pre-trial detention center is an amazing place that combines the incongruous. It happens that you come and ask the prisoners how they are doing, and they answer: “Good!” Just think about it. And we, free people, still have some problems.

My friends and I call these services “virtue on a silver platter.” This opportunity came to us on its own - one day a priest we knew called us and now we go constantly. I believe that this is a real gift to us from the Lord - to directly fulfill His commandment to visit prisoners in prison.