ROMA LOCUTA EST – CAUSA FINITA EST?

On June 16, 1054, the legates (specially authorized ambassadors) of Pope Leo IX, led by his secretary, Cardinal Humbert, entered the altar of the Church of Hagia Sophia in Constantinople. But they did not pray. Humbert placed a document with approximately the following content on the altar of the church. They, the legates, arrived in Constantinople just as God had once gone there before the destruction of Sodom to assess the moral state of its inhabitants. It turned out that “the pillars of the empire and wise citizens are completely Orthodox.” And then followed the accusations against the then Patriarch of Constantinople Michael Cerullarius and, as the document says, “the defenders of his stupidity.” These accusations were very different, starting with the fact that Michael appoints eunuchs as bishops and ending with the fact that he dares to call himself the Ecumenical Patriarch.

The letter ended with these words: “...By the authority of the Holy and indivisible Trinity, the Apostolic See, of which we are ambassadors, [the authority of] all the holy Orthodox fathers of the Seven [Ecumenical] Councils and the entire Catholic Church, we sign against Michael and his adherents - an anathema, which our The Most Reverend Pope spoke against them if they do not come to their senses.”

Text of the anathema cit. by: Vasechko V.N. Comparative theology. Course of lectures.—M.: PSTBI, 2000.—p.8.

Formally, excommunication from the Church (anathema) was pronounced only against the Patriarch of Constantinople, but in reality the entire Eastern Church fell under the streamlined expression: “and his followers.” The ambiguity of this excommunication was further completed by the fact that while the legates were in Constantinople, Leo IX died, and his ambassadors pronounced an anathema on his behalf, when the Pope had already been in the other world for three months.

Pope Leo IX. It was his legates who proclaimed the anathema of 1054 in Constantinople. True, by that time dad himself had already died.

Mikhail Kerullariy did not remain in debt. Less than three weeks later, at a meeting of the Synod of Constantinople, the legates were also anathematized. And neither the Pope nor the Latin Church were affected. And, nevertheless, in the Eastern Christian consciousness, excommunication spread to the entire Western Church, and in their consciousness - to the entire Eastern Church. A long era of divided Churches began, an era of mutual alienation and hostility, not only church, but also political.

We can say that the year 1054 shapes today's world, at least determines the relationship between the Orthodox and Catholic Churches. Therefore, historians unanimously call this division “great,” although nothing great happened for the Christians of the 11th century. This was an “ordinary”, ordinary break in communication between the Eastern and Western Churches, of which there were many during the first millennium of Christianity. At the end of the 19th century, professor, Church historian, V.V. Bolotov counted the years of “war and peace” between the Western and Eastern parts of the still United Church at that time. The numbers are impressive. It turned out that from 313 (the Edict of Milan by Emperor Constantine the Great, which stopped the persecution of Christianity) until the middle of the 9th century, that is, five and a half centuries, relations between the Churches were normal for only 300 years. And for more than 200 years, for one reason or another, they were torn apart (Bolotov V.V. Lectures on the history of the Ancient Church.—T.3.—M.: 1994.—p. 313.).

What do these numbers mean? Not only individual people, but also entire Churches, unfortunately, knew how to quarrel. But then they had the courage to make peace and sincerely ask each other for forgiveness. Why did this particular quarrel, this breakup turn out to be fatal? Was it really impossible to make peace in ten centuries?

Papal ambitions

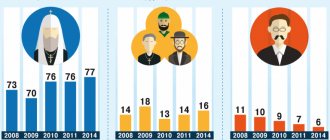

From the 6th century, Roman priests assumed the title of head of the church - pope. At the same time, Western theologians referred to St. Peter, who was the first bishop. Taking advantage of the absence of strong secular power in the West, the popes became independent ecclesiastical and secular rulers in Rome and its surroundings.

The papacy strengthened its power over the episcopate and the entire church hierarchy. Already Gregory I (590-604) called himself the ecumenical head of the church, refusing the Patriarch of Constantinople a similar title. Papal ambitions met resistance both within the church hierarchy and from the head of the Eastern Church and the Byzantine emperor.

ANTIQUE MAGNETS

By the time of the Nativity of Christ, Rome had created a huge empire, which included almost the entire inhabited earth and dozens of peoples. But there were two main ethnic groups - the Romans (Latins) and the Greeks (Hellenes). Moreover, the traditions and culture of these two peoples were so different that it becomes surprising how they were able to create a state, the analogue of which history still does not know. Apparently, this is an illustration of that paradoxical law of nature when magnets with opposite poles attract each other...

The actual culture of the empire was created by the Greeks. The philosopher Socrates, back in the 5th century BC, without knowing it, gave this culture the motto: “Know thyself.” Indeed, man was the focus of any cultural area of the Hellenes, be it sculpture, painting, theater, literature and, especially, philosophy. Personalities such as, for example, Plato or Aristotle were “products” of the ancient Greek mentality, which devoted most of its intellectual energy to speculation and abstract questions of existence. And Greek was the language that any inhabitant of the empire who claimed to be an intellectual knew.

However, the Romans found another “living space” for themselves. They possessed an unrivaled state and legal genius. For example, it’s already the 21st century, and the subject “Roman law” is still studied in law schools. Indeed, it was the Latin ethnos that created the state-legal machine, the system of socio-political and government institutions, which, with some changes and additions, continues to operate to this day. And under the pen of Roman writers, Greek philosophy, abstracted from the realities of life, turned into the practice of social relations and administrative management.

Great Western Schism

Although by that time everything that could have been split was already split, it is worth remembering one more schism, since we have devoted the article to this word, which is not quite familiar to us.

An equally great, but exclusively Western schism occurred, in turn, after the death of Pope Gregory XI, and it continued in the Western Church itself from 1378 to 1417. Then three contenders for this high post declared themselves to be true or real popes.

Their relationship was complex, contradictory and, as we see, lasting for more than one year. We will not now analyze in detail all these matters of long-gone days. Let us only designate the fact of religious strife among the rulers as perhaps the main cause of all these Great and Minor schisms. Which led, in general, to the separation of two Christian churches, close in essence, but now so distant in content.

Yes, the human factor has never been canceled in history...

GROWING DISEASES

Starting from the second half of the 1st century A.D. Christianity begins to win the hearts of the inhabitants of the empire. And in 313, with the Edict of Milan on freedom of religion, Emperor Constantine the Great de jure recognized the right of the Church to exist. But Constantine does not stop there, and in the political space of the pagan empire he begins to create a Christian empire. But the ethnocultural differences between the Eastern and Western parts of the empire do not disappear. Faith in Christ is not born in a vacuum, but in the hearts of specific people raised in a particular cultural tradition. Therefore, the spiritual development of the Eastern and Western parts of the united Church also went completely differently.

The East, with its inquisitive philosophical mind, accepted the Gospel as a long-awaited opportunity to know God, an opportunity that was closed to ancient man. Therefore, it is not surprising that the East fell ill... Saint Gregory of Nyssa (IV century), walking through the streets of Constantinople, describes this disease with surprise and irony: “Some, yesterday or the day before yesterday, took time off from menial work, suddenly became professors of theology. Others, it seems servants, who have been beaten more than once, who have escaped from slave service, philosophize with importance about the Incomprehensible. Everything is full of this kind of people: streets, markets, squares, crossroads. These are clothing merchants, money changers, and food sellers. You ask them about obols (kopecks - R.M.), and they philosophize about the Born and the Unborn. If you want to know the price of bread, they answer: “The Father is greater than the Son.” Can you handle it: is the bathhouse ready? They say: “The son came from nothing.”

This happened not only in Constantinople, but throughout the East. And the disease was not that money changers, salesmen or bathhouse attendants became theologians, but that they theologized contrary to Christian tradition. That is, this disease of the church body developed according to the logic of any other disease of a living organism: some organ ceases to perform its function and begins to work incorrectly. And then the body throws all its strength into restoring order within itself. The five centuries following the Edict of Milan in church history are usually called the era of the Ecumenical Councils. With them the church body healed itself from heresies. This is how dogmas—the truths of faith—appear. And although the East was ill for a long time and seriously, the Christian doctrine was crystallized and formulated at the Councils.

First Ecumenical Council

While the eastern part of the Christian empire was shaken by “theological fever,” the western part was striking, in this regard, with its calm. Having accepted the Gospel, the Latins did not cease to be the most governmental people in the world, did not forget that they were the creators of exemplary law, and, as Professor Bolotov aptly noted, “understood Christianity as a divinely revealed program of social order.” They had little interest in the theological disputes of the East. All the attention of Rome was directed to solving practical issues of Christian life - rituals, discipline, governance, and the creation of the institution of the Church. By the 6th century, the Roman See subjugated almost all the Western Churches, with which a “dialogue” was established according to the famous formula - Roma locuta est - causa finita est? (Rome said - and the matter is over).

Already in the 4th century, a unique teaching about the Bishop of Rome began to develop in Rome. The essence of this doctrine is that Popes are the successors of the Apostle Peter, who founded the Roman See. In turn, Peter received authority over all the other apostles, over the entire Church from Christ Himself. And now the successors of the “prince of the apostles” are also the successors of his power. Those Churches that do not recognize this fact are not true. The heretical worries of the East, which never recognized the doctrine of papal primacy, and the calm of the West, which was under the Roman omophorion, only added to the popes' confidence in their own rightness.

The East has always respected the Roman See. Even when Emperor Constantine the Great moved the capital to the shores of the Bosphorus, to the city of Byzantium, the Bishop of Rome came first in all church documents. But, from the point of view of the East, this was a primacy of honor, not power. However, the Roman legal spirit drew its own conclusions from this first passage. And, besides, the doctrine of the power of the Pope over the Church grew in Rome with the permission and, one might say, even with the help of the Eastern Church itself.

Firstly, in the East they were strikingly indifferent to the claims of the Roman bishops. Moreover, when the Easterners needed the support of Rome against heretics (or, conversely, heretics against the Orthodox), they ingratiatingly turned to the Pope. Of course, this was nothing more than a play on words, but for the West it meant that the East recognized the authority of the Roman see and its bishop over itself. Here, for example, are lines from the message of the IV Ecumenical Council to Pope Leo I: “You came to us as the interpreter of the voice of blessed Peter and extended the blessing of his faith to everyone. We could declare the truth to the children of the Church in a community of one spirit and one joy, participating, as at a royal feast, in the spiritual joys that Christ prepared for us through your letters. We were there (at the Council - R.M.), about 520 bishops, whom you led, as the head leads the members.”

Over the first millennium of the history of the Church, dozens of similar pearls came from Eastern pens. And when the East woke up and seriously paid attention to the claims of the Roman bishops, it was already too late. The West presented all this florid rhetoric and rightly remarked: “Written by you? Why are you now retracting your words?” The Eastern Church tried to justify itself, which does not give the rhetoric a precise legal meaning. But in vain. From the point of view of Rome, the East turned out to be an unholy apostate from the faith of the fathers, who wrote that “Rome is the interpreter of the voice of blessed Peter.” This conflict was reflected in a complete misunderstanding of each other’s psychology and ethno-cultural realities.

Secondly, the East, busy with its dogmatic disputes, paid almost no attention to the church life of the West. It is impossible to name a single decision made there under the influence of the Eastern Church. For example, the emperor, convening the Ecumenical Council, invited bishops from the smallest and most insignificant dioceses of the East. But he communicated with Western dioceses exclusively through the mediation of Rome. And this also elevated the former capital in the eyes of Western bishops, and, of course, in their own eyes.

Finally, another reality that influenced the final break is geopolitical. It should be noted here that the inhabitants of the eastern part of the Roman Empire themselves never called themselves Byzantines (this name appeared only after the Great Schism). After the West fell victim to the Great Migration in the 5th century, the East became the sole successor to the Roman Empire, so its inhabitants called themselves not Byzantines, but Romans (Romans). The idea of a Christian empire involved three components - the Christian faith, imperial power and Greek culture. All these three components presupposed the idea of universality. Moreover, this concerned the Roman Emperor. The very idea of a single Christian empire assumed that there could only be one emperor. All kings and rulers are subject to him.

Charlemagne, the first barbarian king who encroached on the right to be called Emperor and thereby oust Byzantium

And so, in the 8th century, the Frankish king Charles I created a huge state on the territory of the western part of the Roman Empire. Its borders extended from the Pyrenees and the Atlantic Ocean in the west to the Adriatic Sea and the Danube in the East. From the coast of the North and Baltic Seas in the north to Sicily in the south. Moreover, Charlemagne did not want to obey Constantinople at all. In fact, it was a completely different empire. But, as already mentioned, the ancient worldview could not tolerate the existence of two empires. And we must pay tribute to the Popes - they stood for Constantinople to the end, feeling the thousand-year tradition of the Romano-Hellenic community.

Unfortunately, with its then policy, Constantinople with its own hands pushed Rome into the arms of the Frankish kings. And in 800, Pope Leo III crowned Charlemagne as “Emperor of the Romans,” thereby recognizing that the real empire was here in the West. All this happened against the backdrop of a catastrophic reduction in the territory subject to the Emperor of Constantinople (in fact, in the 9th century, as a result of the Arab conquests, it became limited to the outskirts of Constantinople). And Karl gave his state a slightly wonderful name: “The Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation,” which survived until the beginning of the 19th century.

All these events served to further alienate Constantinople and Rome. Although fragile church unity continued to persist over the next two centuries. The thousand-year-old cultural and state community of the Greeks and Romans had an impact here. The relations between the Greeks and the Germans (Franks) were different. Yesterday's pagans and barbarians absolutely did not value the theological heritage of the Hellenes, subconsciously understanding their gigantic superiority not only in culture, but also in churching. Both Emperor Henry III, Pope Leo IX (a relative of the emperor), and Cardinal Humbert, who led the schism, were Germans. This is probably why it turned out to be easier for them to destroy the fragile peace between the Churches...

Many church historians come across the idea that the West deliberately made a break with the East. What is this statement based on? By the 11th century, it became obvious to the West that, while agreeing with the historical primacy of the honor of the Pope before his four patriarchs, the East would never agree with the primacy of the Pope’s power over the Universal Church and would never recognize his autocracy as a Divine institution. Therefore, Rome, according to the logic of the doctrine of papal primacy, had only one thing left to do - to declare that all the Churches obedient to the Pope are the true Church. The rest excommunicated themselves from it, not listening to the “divine voice of the successor of the Apostle Peter.” “The rest” are all the Eastern Churches...

It’s a shame that even at the critical moment of the rupture and several centuries after it, the Eastern Church could not understand its real cause. What came first was not the Pope's claims to autocracy in the Church, but ritual differences. The Easterners accused the Westerners of fasting on Saturday, celebrating the Liturgy not on leavened bread, but on unleavened bread, etc. All this testified to the deep ignorance and decline of Byzantine Orthodoxy at the turn of the millennium. There were no people in the East at that time who could remind us that the Church has never been and cannot be divided by culture, traditions, or even rituals.

So, the main reason for the division was precisely the doctrine of the power of the Pope over the Church. And then events followed their own internal logic. Confident in his absolute power, the Roman bishop, alone, without a Council, makes a change to the Christian Creed (“filioque” - the doctrine of the procession of the Holy Spirit not only from God the Father, but also from the Son). This is where theological differences between West and East begin.

But even in 1054 the Schism did not become self-evident. The last thread between West and East was broken in 1204, when the Crusaders barbarously sacked and destroyed Constantinople. And the word “barbaric” is not an epithet here. In the minds of both the crusaders and the Roman high priests who blessed these campaigns, the East was no longer Christian. In the eastern lands, in cities where episcopal sees existed, the Latins established their own parallel hierarchy. Anything could be done with the shrines of the East: destroy its icons, burn books, trample on the “Eastern crucifix”, and take the most valuable things to the West. Very soon the East began to pay the West in the same coin. It was after the era of the Crusades that the Great Schism became irreversible.

Orthodox and Catholics

Why do I think that it was the Roman Church that fell away from Orthodoxy, and not vice versa? The answer is simple, Christianity spread precisely from east to west. All theological life arose and flourished in the east. Yes, Rome did not fall into heresy until the schism of 1054, but this was partly dictated by the low level of development of theology (it began to develop later, in the 11th century with the advent of scholasticism). This was an objective consequence of the decline that dominated the West with the collapse of the Western Roman Empire for several centuries. Gradually, Rome separated itself from all other eastern churches, creating a new church order in the west, the center of which was Rome. As a result, this led to a conflict with the “old” churches, which were not characterized by this new teaching.

The history of the split of the Christian world into Orthodoxy and Catholicism is a tragedy that has not been overcome for almost 1000 years. I don't claim to have covered all the reasons. But, I just wanted to draw attention to the fact that behind any tragedy lies a long story in which many factors are closely intertwined. People often become only victims of circumstances and the big game of politicians.

Author: priest Alexander Danilov

RETURN ATTEMPT

Subsequent history sees attempts to overcome the Schism. These are the so-called unions: Lyon and Ferraro-Florentine. And here, too, there was a complete misunderstanding of each other’s psychology. For the Latins, the question was simple: you can leave your liturgical rite, language and even the creed to be sung without the filioque. The only requirement is complete submission to the Bishop of Rome. For the Greeks, in both cases it was about saving Constantinople from the Turks, and, having concluded a union, they immediately abandoned them upon arrival in the capital.

Pope Gregory the Great (540-604) is revered by the Eastern Church as the guardian of the Orthodox faith and its canons. Gregorian chants are named after him.

How does the Orthodox Church relate to the Great Schism? Is it possible to overcome it? Despite centuries of misunderstanding and strife between Orthodox and Catholics, in fact, there is only one answer - it is a tragedy. And overcoming it is possible. But the paradox is that for centuries almost no one felt any particular tragedy in the Great Schism, and almost no one wanted to overcome it either. In this sense, the words of the Orthodox priest Alexander Schmemann, the famous theologian of the Russian emigration, are very true:

“The horror of the division of Churches is that over the centuries we have not encountered almost a single manifestation of suffering from division, longing for unity, consciousness of abnormality, sin, the horror of this schism in Christianity! It is dominated not by the consciousness of the impossibility of choosing unity over Truth, of separating unity from Truth, but by almost satisfaction with separation, the desire to find more and more dark sides in the opposite camp. This is the era of division of Churches, not only in the sense of their actual separation, but also in the sense of the constant deepening and widening of this ditch in the consciousness of church society” (Archpriest Alexander Shmeman. The historical path of Orthodoxy. - M.: 1993. - P. 298).

The paradox is that formally the Orthodox and Catholic Churches have long been reconciled. This happened on December 7, 1965, when the Patriarch of Constantinople and the Pope met in Istanbul and lifted the anathemas of 1054. The Roman Catholic and Orthodox Churches were proclaimed "Sister Churches". Did all this reconcile them? No. Yes, and could not reconcile. The handshake of churches and the handshake of people are somewhat different things. When people shake hands with each other, then in their hearts they may well be enemies. This cannot happen in the Church. Because it is not external things that unite the Churches: the identity of rituals, priestly vestments, the duration of services, church architecture, etc. Truth unites the Churches. And if it is not there, the handshake turns into a lie, which gives nothing to either side. Such a lie only fetters the search for real, internal unity, reassuring the eyes that peace and harmony have already been found.

Background to the Great Schism

Thus, the so-called Acacian schism (484-519) lasted for 35 years, which arose due to religious discrepancies in the Henotikon, a special religious message that the Byzantine emperor Zeno sent to believers with a call to unite and stop conflicting. However, some people thought differently from the fathers mentioned in the Henotikon...

Further, from 863 to 867, the next Photius schism lasted between the Roman Papacy and the Patriarchate of Constantinople, which arose as a result of an ambiguous interpretation of the legality of the accession to the throne of Patriarch Photius...

And when the Christian Church began to transform from a persecuted sect into a rich and prosperous religious system, the disagreements between its parishioners not only did not disappear, but only multiplied many times over.