Historical sketch

In the Old Testament Church, the temple liturgical language was Hebrew, which united all the faithful and contributed to the identification of church unity with the unity of the Jewish people. The introduction of other languages was allowed only at an auxiliary level, in synagogues, after the Jews lost their ancient spoken language in the 6th century. BC. It is known that in synagogues the translation and interpretation of the Holy Scriptures began to be carried out in common speech - Aramaic and Greek; There was also a translation of the Scriptures into Syriac [1].

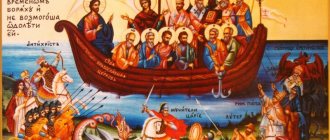

A striking distinctive feature of the New Testament Church was the multilingual unanimity, miraculously established by God during the descent of the Holy Spirit on the apostles and allowing the disciples of the Lord Jesus Christ to fulfill His commandment to teach “all nations” (Matthew 28:19). While maintaining Hebrew, Aramaic and Syriac in liturgical use, the Christian Church quickly made Greek the most common language of communication of the Roman Empire as the most common language of its worship. In the 3rd century, Tertullian writes about the existence of liturgical texts in Latin [2]. Evidence from centuries has been preserved of the translation of Christian liturgical texts into Coptic [3], Gothic [4] and Ethiopic [5] languages, and from centuries - of the creation of original liturgical texts in Armenian [6]. The appearance of the first liturgical translations into Georgian also dates back to centuries [7].

Subsequently, the Roman Church followed the path of universally imposing worship in Latin, so that by the century the Slavic first teachers, Equal-to-the-Apostles Cyril and Methodius, were forced to fight the “trilingual heresy” that was widespread there, according to which only three languages of the title from the Cross of the Lord - Hebrew, Greek and Latin - were acceptable for worship. In the East, the Orthodox Church retained a living consciousness of the multilingualism of church life and focused its apostolate on liturgical translation. In his denunciation of Western “trilingualism,” Equal-to-the-Apostles Cyril pointed out:

«

...we know many generations, know books well, and give glory to God with our own tongues. I am the essence of these: Ormeni, Piersi, Avazgi, Iverie, Sugdi, Goti, Obre, Tursi, Kozare, Arabians, Egyptians, Suri, and many

» [8].

The Equal-to-the-Apostles brothers themselves created Slavic writing, serving to introduce the Slavic language into worship, which quickly became the third richest literature in Europe.

In the subsequent era, the spread of Orthodoxy among peoples alienated from it was carried out primarily by the Russian Church, which over time continued to create new liturgical translations. In the 14th century, Saint Stephen of Perm, who preached to the Zyryans, created a written language for them and translated the main liturgical texts into their language. From the middle of the 18th century, the publication of liturgical texts in Ossetian began. In the 19th - early centuries, there was a surge in missionary activity in the Russian Church, organized since 1870 under the auspices of the All-Russian Orthodox Missionary Society. During this period, Orthodox worship was introduced in a number of languages of the peoples of the Russian Empire (including Aleutian by Saint Innocent (Veniaminov), Altai by Saint Macarius (Glukharev), Tatar by Saint Macarius (Nevsky), Yakut by Bishop Dionysius (Khitrov), and many others), and in foreign missions - also in Chinese, Japanese, Korean and English.

At the same time, among the peoples of Eastern Europe that had long been attached to the Church, there was a gradual replacement of Greek and Church Slavonic with modern languages. Thus, in the period from the 16th to the 19th centuries, the liturgy of the Romanian lands almost completely switched to Romanian. Since the 19th century, the process of introducing modern Bulgarian and Serbian into worship began, along with Slavic. Finally, in the first half of the century, along with the formation of the corresponding local Churches, the liturgical use of Albanian, Polish, Czech and Slovak was established.

The turmoil that befell the homelands of the original Orthodox peoples in the century, especially the rise and fall of communist regimes, as well as the growing pressure on Christians in the Middle East, contributed to the emergence of a large Orthodox diaspora around the world. Together with the shaking of the previous foundations of Western countries and a certain openness to Orthodoxy, this played a decisive role in the introduction of the most important Western European languages into the worship of the Orthodox Church. Since the second half of the century, a new missionary movement in the Greek Churches began to gain strength, manifesting itself with particular brightness in Africa, where by the beginning of the 21st century translations of Orthodox worship into more than 50 local languages appeared. Finally, the revival of the Russian Church made it possible to resume the extinct liturgical languages of the post-Soviet space and begin worship in a number of previously unused ones.

Which Christians are the most

Who are Catholics? These are representatives of Catholicism (from the Greek word “universal”, “ecumenical”) - one of the three main movements of Christianity along with Orthodoxy and Protestantism. Catholics are the largest Christian denomination: today there are more than 1.3 billion people.

“As soon as this incorrect wisdom had time to appear in the West, that the Holy Spirit also proceeds from the Son, it... little by little introduced with it other novelties, for the most part contradicting the commandments of our Savior clearly depicted in the Gospel, such as: sprinkling instead of immersion in The Sacrament of Baptism, the taking away of the divine Chalice from the laity and the use of unleavened bread instead of leavened bread, the exclusion of the invocation of the Holy Spirit from the Liturgy. It also introduced innovations that violated the ancient apostolic rites of the Catholic Church, such as: the exclusion of baptized infants from Confirmation, the exclusion of married men from the priesthood, and so on” (Reverend Ambrose of Optina).

Cathedral of Santa Maria del Fiore (Florence) - one of the most famous Catholic churches

Current state

In the modern use of the Orthodox Church there are dozens of languages in which the main divine service of the Church, the Divine Liturgy, is performed at least occasionally. Only seven of them - Albanian, English, Arabic, Greek, Georgian, Romanian and Church Slavonic - can clearly be called the main languages of the autocephalous Churches, but the total number of liturgical languages has increased significantly in recent years and continues to increase. The Orthodox liturgical languages now include:

- Albanian

- Aleutian

- Altaic:

- The main liturgical language in the parishes of the Gorno-Altai diocese, where Altaians predominate among the believers (now the parishes of the Ulagansky district of the Altai Republic in Russia); It is also used in other parishes of the diocese.

- It was introduced into worship by the Monk Macarius (Glukharev), his assistants and students, as part of the Altai spiritual mission, from the middle of the 19th century. By 1865, the Divine Liturgy of St. John Chrysostom was translated and printed in Altai, and permission was received from the Holy Synod to perform divine services in the Altai language. Divine services were conducted in Altai until the defeat of the mission at the beginning of the century. The resumption of services in Altai for the Altai people was one of the first blessings of Bishop Kallistrat (Romanenko) upon his elevation to the newly established Gorno-Altai See in 2013. As of 2015, “services are performed entirely in the Altai language only in the Ulagansky district,” and part of the language is also used in other parishes [9].

- The main liturgical language of the Antiochian Orthodox Church; used in the Alexandria and Jerusalem Orthodox Churches - in those dioceses and parishes where the majority of the flock are Arabic-speaking believers.

- After the conquest by the Arabs in the 7th-8th centuries of almost the entire canonical territory of the Alexandria, Antioch and Jerusalem Orthodox Churches, the use of the Arabic language began to expand here, which soon began to be introduced into worship, along with Greek and Syriac. The translation of basic Christian texts, including liturgical texts, from Greek and Syriac into Arabic began first in such monasteries of the Jerusalem Church as the Lavra of Saint Sava, the Faran Lavra and the Sinai Catherine Monastery - the earliest translations are believed to date back to the 770s [10 ]. In the Alexandrian Church, the transition of the majority of Orthodox Christians to Arabic in everyday life, literature and worship occurred towards the end of the century [11]; in the Antiochian Church, Arabic gradually became the main liturgical language in the 13th century [12]. At the same time, in the Churches of Alexandria and Jerusalem, Greek retained a dominant position among the clergy, so that only in the Patriarchate of Antioch did Arabic become the main liturgical language.

- It is used to nourish the local Aramaic-speaking population in several churches and monasteries of the Antiochian Church, as well as in individual communities in the diaspora (one Assyrian parish with Aramaic worship is known in the village of Old Kanda (Dzveli Kanda) of the Mtskheta municipality of Georgia under the omophorion of the Georgian Church).

- The Aramaic language, spoken by the Lord Jesus Christ Himself, was one of the auxiliary liturgical languages of the Church already in the Old Testament era. The New Testament Church inherited and expanded its liturgical use, primarily in the Middle East. The massive apostasy of local Christians from Orthodoxy after the condemnation of Nestorianism and Monophysitism in the century, and then the gradual transition of the region to the Arabic language after the Arab conquest of the 7th-8th centuries led to the extinction of Aramaic worship in the Orthodox Church. However, isolated islands of Aramaic liturgical life were preserved over subsequent centuries under the omophorion of the Antiochian Orthodox Patriarch. Thus, at the beginning of the 21st century, Orthodox services in Aramaic were held in churches in Maaloula and Saydnaya in Syria. The dispersion of Christians from the Middle East led to the use of Aramaic worship in places of their compact residence - in particular, as of 2015, services were performed in Aramaic for Assyrians in the village of Dzveli Kanda (Old Kanda) of the Mtskheta municipality of Georgia under the omophorion of the Georgian Church [13].

- It is used in a number of parishes of the Jerusalem Orthodox Church for the care of Hebrew-speaking believers.

- The language of worship of the Old Testament Church, Hebrew remained in the liturgical use of Jewish Christian communities in the first centuries of the New Testament era, but gradually assimilation with neighboring peoples led to the extinction of this tradition. After a centuries-long break, a big step towards the revival of Orthodox worship in Hebrew was made in the Russian Church - in 1841 Vasily Levison translated the liturgy of St. John Chrysostom in biblical Hebrew for the Russian spiritual mission in Jerusalem [14]. With the revival of Hebrew as the dominant language in Israel, the question of caring for Hebrew speakers gradually arose in the Jerusalem Orthodox Church and since the early 1980s, largely thanks to the efforts of the Jewish priest Fr. Elijah Shmain, Hebrew began to gradually return to Orthodox worship [15].

- It is used in a number of parishes of the Mari Metropolis for the care of the Mari.

- The introduction of the Mari language into worship took place within the framework of a project of the Missionary Department of the Yoshkar-Ola Diocese, which received support from the “Orthodox Initiative” grant competition of the Russian Orthodox Church. The project provided for the translation of the Divine Liturgy into the Mari language, the publication of music collections with liturgical chants and the performance of missionary visiting services in 15 villages in the north-east of the republic of the diocese populated mainly by Mari. The implementation of the project began on May 1, 2014, the chants of the Divine Liturgy in the Mari language were set to everyday chants. The first liturgy in the Mari language was celebrated on June 5 of that year in the house church of the Yoshkar-Ola diocesan administration in honor of the “Three-Handed” icon of the Mother of God. This service was attended by all project participants, as well as Archbishop of Yoshkar-Olinsky John (Timofeev). Mobile services were held in three summer months. In subsequent years, the performance of divine services in Mari began to spread in a number of parishes of the diocese (from 2021 - the Mari Metropolis) [16].

- Used in the parishes of the Kryashen deanery of the Tatarstan Metropolitanate and by the Tatar Orthodox community at the Moscow St. Thomas Church on Kantemirovskaya.

- In 1846, Emperor Nicholas I Pavlovich ordered the translation of church services into the Tatar language. Translations, which were originally desk work, began to quickly be replenished and put into practice in the 1860s in connection with the opening of Nikolai Ilminsky’s Baptized Tatar school in Kazan, followed by other schools in different villages. Thanks to the work of Saint Macarius (Nevsky), it became possible to celebrate the first Divine Liturgy in Tatar (Kryashen) for students of the Kazan Epiphany Tatar school on the day of the Triumph of Orthodoxy on March 9, 1869. Subsequently, worship in the popular language spread to a number of Kryashen parishes and continued until the suppression of church life after the revolution [17]. Patriarch Alexy I of Moscow blessed the use of the mother language of the Kryashens in their parishes [18], but a full resumption of church life became possible only at the end of the century. A special Kryashen parish was re-established with the blessing of Bishop Anastasy (Metkin) of Kazan and began its liturgical life on December 23, 1989, when the Kryashen liturgy was again celebrated in the Kazan Intercession Church. Subsequently, the Kazan parish was joined by others, united in the Kryashen deanery of the Kazan diocese with its center in the Kazan Tikhvin Church [19]. As the work of translating the Holy Scriptures and liturgical texts developed, the question arose about the distinction between the church-Kryashen and modern Tatar liturgical languages. No later than 2014, the Moscow community of Orthodox Tatars undertook a new translation of the prayer book [20]. As of 2015, Church Kryashen was the main liturgical language in eight parishes of the Tatarstan Metropolis [21].

- It is used regularly at the services of the Peter and Paul Udmurt parish of the St. Nicholas Church at the Izhevsk Alexander Nevsky Cathedral and the Kosmodamian parish in the village of Nyrya, Kukmorsky district of Tatarstan; away services are held in a number of parishes of the Udmurt and Tatarstan metropolises for the care of the Udmurts.

- The translation of liturgical texts into Udmurt (at that time known as “votsky” or “votyatsky”) and their implementation in life in the second half of the 19th century are associated with the works of the translation commission under the leadership of Nikolai Ilminsky, but these undertakings were interrupted by revolutionary upheavals and the destruction of church life after 1917. During the Soviet period, only isolated pockets of Udmurt were preserved in the Church’s worship - thus, in the middle of the century, the tradition of performing services in Udmurt was preserved in the Izhevsk Assumption Church [22]. With the fall of the atheistic system, in the 1990s the publication of liturgical books and the improvement of liturgical translations in Udmurt began again. The first divine liturgy in Udmurt in the new period was celebrated on December 25, 2005 in the Izhevsk Church of the Exaltation of the Cross [22]. Since the fall of 2006, regular services in Udmurt began to be held in Izhevsk at the newly formed Udmurt parish, which met at different times in different churches of the city [23]. As of 2006-2007, in addition to Izhevsk, regular services in Udmurt were also held at one parish of the Kazan diocese - Kosmodamianovsky in the village of Nyrya, Kukmorsky district [24]. To care for the Udmurt-speaking believers, regular visiting services of the clergy and activists of the Izhevsk Udmurt community began to be held at the parishes of the Udmurt and Tatarstan metropolises at the invitation of local abbots [25].

- It is used as a liturgical language in the Bac diocese of the Serbian Church for the care of the Roma; also, if necessary, it is occasionally used in other parishes of the Serbian and Romanian Churches.

- The translation of the Divine Liturgy into Romani was carried out with the blessing of Bishop Irinej (Bulovich) of Bac in Novi Sad, Serbia, in 1993 [26]. Since that time, the Liturgy in Gypsy began to be celebrated occasionally in the Bac diocese and in other parts of the Serbian Church. Subsequently, the Gypsy language was also introduced into use by the Romanian Church - in 2006, a prayer book in Gypsy was published here, and on December 23, 2008, Bishop Barsanuphius (Gojescu) of Prachovo celebrated the Gypsy liturgy for the first time in the Bucharest Radu Vodă monastery [27].

- It is used in a number of parishes of the Chuvash Metropolis, as well as in some churches in Samara and Kazan, to nourish the Chuvash.

- The comprehensive introduction of the Chuvash language into liturgical use began by the end of the 1870s, thanks to the work of the translation commission under the leadership of Nikolai Ilminsky [28]. Divine services in Chuvash were widespread until the destruction of church life in the 1920s-1930s, and began to be performed again in the predominantly Chuvash parishes of the Cheboksary diocese in the second half of the century. By the end of the Soviet period, most churches in the diocese conducted services in Chuvash [29].

Catholic churches

The Universal Catholic Church is divided into Latin Rite Catholicism and Eastern Rite Catholicism. The head of the Catholic Church is the Pope, who heads the Vatican City State in Rome. The classification position of Apostolic and Liberal Catholics is uncertain - various religious scholars classify them as non-Roman Catholicism, fringe Catholicism, Pentecostalism, or the syncretic New Age movement.

| Roman Catholicism | Non-Roman Catholicism | Marginal Catholicism |

| Latin Rite Catholicism | Old Catholicism : Old Catholic Church of Germany, Old Catholic Church of Austria, Old Catholic Church of the Netherlands, Christian Catholic Church of Switzerland, Polish National Catholic Church, Polish National Catholic Church of America | Apostolic Catholicism : Catholic Apostolic Church (Germany and England), New Apostolic Church (Germany, South Africa, etc.) |

| Eastern Rite Catholicism : Greek Catholics (particularly Ukrainian), Maronites, Syro-Catholics, Syro-Malabarians, Coptic Catholics, Ethiopian Catholics, Armenian Catholics, Chaldeans | Conservative Catholicism : Brazilian Catholic Apostolic Church, Catholic American Orthodox Church, Mexican Orthodox Catholic Apostolic Church, Catholic Apostolic Gallican Church, Old Romanesque Catholic Church of France, Old Catholic Mariavite Church of Poland, African Legion of Mary (Kenya), National Catholic Apostolic Church | Liberal Catholicism : Orthodox Catholic Church, Autocephalous Gallican Catholic Church, Apostolic Gnostic Church (all 3 in France), Liberal Catholic Church USA |

| Reformed Catholicism : Philippine Independent Church, Czech Hussite Church | ||

| Anglo-Roman Catholicism (Anglo-Catholicism) : Free Protestant Episcopal Church of Great Britain, Free Protestant Episcopal Church of Nigeria, African Orthodox Church of Zimbabwe, African Orthodox Church of South Africa | ||

| Catholic churches headed by independent bishops (“epissori vagantes”) : Catholic Apostolic Orthodox Church of the East (Alouette-Pessac, Gironde, France), Mixed independent main parish East-West (Beham Missionary Abbey, France) |

Literature

- Collinge, William J. Historical Dictionary of Catholicism. 1997

- McBrien, Richard P., ed. The HarperCollins Encyclopedia of Catholicism. 1995

- Yuri Tabak. Orthodoxy and Catholicism. Major dogmatic and ritual differences

- E. N. Tsimbaeva. Russian Catholicism. The forgotten past of Russian liberalism

- Coleman, Lisa M., et al. Basics of the Catholic Faith. 2000

- Froehle, Bryan T., Mary L. Catholicism USA: A Portrait of the Catholic Church in the United States. 2000

- Burns, Robert A. Roman Catholicism after Vatican II. 2001

And also: Christian prayer “Creed” in Latin:

Prayer Pater noster in Latin

PATER NOSTER, qui es in caelis, sanctificetur nomen tuum. Adveniat regnum tuum. Fiat voluntas tua, sicut in caelo et in terra. Panem nostrum quotidianum da nobis hodie, et dimitte nobis debita nostra sicut et nos dimittimus debitoribus nostris. Et ne nos inducas in tentationem, sed libera nos a malo.

Song Credo in Latin

Circulus Latinus Panormitanus is one of the best sites dedicated to modern Latin.

Latin: Catchphrases, Aphorisms and Expressions - an authoritative collection of aphorisms, catchphrases and sayings in Latin.

Catholic art

A special, Catholic style of fine art developed during the Renaissance and received its most perfect expression in the Roman Baroque, also called the “art of the Counter-Reformation.” The school of Roman classicism, which developed under the influence of the work of Raphael, was close to this direction. The most prominent representative of the Catholic style of this time was the painter, the Dominican monk Fra Bartolommeo della Porta (1475-1517), the author of large altar paintings, the beauty and three-dimensionality of which was improved by the artists of the Florentine school, especially Fra Angelico (1387-1455). The aesthetics of Catholicism were also embodied in the French Renaissance and Mannerism, the styles of Flemish, Spanish and South German Baroque and in the art of Latin America.