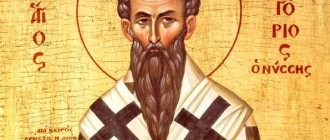

| St. Gregory Palamas. Icon last third of the 14th century Collection Pushkin Museum. |

Gregory Palamas

(Greek Παλαμα̃ζ; 1296 - 1359), Metropolitan of Thessalonica, saint, theologian of hesychasm, father and teacher of the Church Commemorated November 14, the week of the 2nd week of Great Lent, in the Councils of the Athos Saints and Vatopedi Saints (Greek), and also together with his holy family (on the first Sunday after November 14, as well as December 18) (Greek)

Born in 1296 in Constantinople into a wealthy family. The education and training of Gregory Palamas was led by the best teacher of his era - Theodore Metochites, a major political figure, philosopher and writer, a great logothete under Emperor Andronikos II Palaiologos [1].

Refusing the secular career of a dignitary offered to him, at the age of 20 he accepted monasticism in one of the Athos monasteries. He spent about three years with his spiritual mentor Nicodemus the Hesychast of Vatopedi, from whom he took monastic vows. Later, his spiritual mentor was St. Gregory of Byzantium. The teacher of Saint Gregory in hesychast practice was the Venerable Nicephorus the Solitary, who labored on Mount Athos. His teachers also became the Patriarchs of Constantinople Gregory II of Cypriot and Athanasius I, as well as Saint Theoliptus of Philadelphia [2].

In 1336, at the monastery of St. Sava, he began theological works, which he did not abandon until the end of his life.

His dispute with Barlaam of Calabria and Akindinos about the Tabor light is especially famous; In this dispute, Palamas defended the teaching of the Church that this light is not creation, but ever-present light (uncreated; see also hesychasm). On this occasion, in 1341, a Council was convened in the St. Sophia Church of Constantinople under the chairmanship of the Patriarch, at which Palamas exposed the error of Varlaam so that the latter decided to retire to Italy.

In 1344, Patriarch John XIV Cripple, an adherent of the teachings of Varlaam, excommunicated Saint Gregory from the Church and imprisoned him. In 1347, after the death of John XIV, the ascetic was freed and elevated to the rank of Archbishop of Thessalonica by Patriarch Isidore I Vukhir, his friend and comrade-in-arms. On one of his trips to Constantinople, a Byzantine galley fell into the hands of the Turks, and the saint was sold in various cities for a year. Only three years before his death, Saint Gregory returned to Thessaloniki.

Died peacefully on November 14, 1359.

| St. Gregory Palamas. Fresco approx. 1371 Painting of the Church of the Holy Unmercenaries of the Athos Vatopedi Monastery. |

Controversy with Varlaam

The Athonite monks were extremely agitated by Varlaam’s attacks and turned to one of the outstanding Byzantine ascetics and scientists, Gregory Palamas, with a request to talk with Varlaam and convince him to stop verbal and written attacks on them and not to insult the holy men who worship the divine fire.

Palamas, who had previously had reason to speak out against the theological and philosophical views of Varlaam, now with all the strength of his scientific talent and literary skill spoke out against the detractor of Byzantine monasticism and his harsh judgments about godly hesychia.

He wrote (during the period 1338-1340) nine words against Varlaam, dividing them into three triads. Varlaam responded to his literary opponent with the essay “Κατα ̀ μασαλιανω̃ν” (“Against the Messalians”). Other persons also intervened in the dispute: Palamas found sympathy for himself with the Ecumenical Patriarch Philotheus, Queen Anna and her son John Palaeologus, with the courtier, and later emperor, John Cantacuzene and, of course, among the Byzantine, especially the Athonite silent ones, and Varlaam had supporters in personified by the theologian and philosopher Gregory Akindinus and the historian Nikifor Grigora. Thus, two parties were formed - the Barlaamites and the Palamites - and the dispute flared up with great force.

The whole burning subject of the dispute was focused on the question of the being in the energy of the Divine (ή Θεία ουσία καὶ ὲνέργεια): whether energy is the very being of God or not. We came to the formulation of this question through another: what was the light of the Lord's Transfiguration on Tabor - the being of God or not.

Varlaam's main idea was that divine insight is science and knowledge, which is given to those who are pure in heart and fulfill the commandments of God. Such was precisely the illumination of the disciples by the light of the Lord during the awakening on Mount Tabor; it had the purpose of communicating the highest knowledge to the apostles and was not by its nature something immaterial or an outpouring of the very essence of God, but only a ghost, a mental image created precisely for this purpose.

Palamas and the Athonite monks defended the opinion that the light that shone on Tabor, according to the teachings of the Fathers of the Church, although it is not the very essence of God, is not a mental image: it is an inseparably inherent manifestation and realization of the Divine being, otherwise it is a natural property and energy (φυσικη ̀χάριζ καί ένέργεια) of the Deity.

Varlaam objected to this: if the illumination of the disciples on Tabor was the effect of the communication of the Divine being to them, then we must conclude that this light is identical with the being of God and that the being of God can be communicated to man and is accessible to human feelings.

Not a being, answered Palamas, but Divine energy, grace and glory, given from the essence of God to the saints. Moreover, Divine energy is inseparable from the essence of God, just as the Son is inseparable from the Father or the Holy Spirit, or as a ray is inseparable from the sun and heat from fire; This means that in such a teaching there is no thought of bitheism. And just as the being of the sun, i.e. His disk is indivisible above the rays and radiance sent by the human eye, in the same way, according to the teachings of the church, the divine being is indivisible and invisible above the radiances, energies and goodness sent to him, which is communicated to the saints by the Most Holy Trinity.

Varlaam and his supporters objected to this understanding of the relationship between the essence of the Divine and His energy and in further polemics came to pantheistic views.

Varlaam's teaching as heretical caused condemnation by the Church. Councils were convened about him in 1341, 1347, 1351, 1352 and 1368. At these councils, the teaching of Palamas and his supporters was recognized as being in agreement with the teaching of the church, and Varlaam and his disciples were anathematized. In 1351, the saint himself, following Patriarch Callistos, signed the Council Tomos against like-minded people Varlaam and Akindinus [3].

| Icon of St. Gregory Palamas |

The results of the conciliar decisions were expressed in the following articles of the Synodik, proclaimed on the Week of the Triumph of Orthodoxy, which were included in its composition in 1352:

- Anathema to those who accept the light that shone from the Lord during His Divine Transfiguration, either as an image or a creature or a ghost, or as the very being of God, and who do not confess that that Divine light is neither a being of God nor a creature, but an uncreated and physical grace and the radiance and energy that always comes from the very being of God.

- Anathema to those who accept that God has no physical energy, but only one being, and that there is no difference between the being of God and energy, who does not want to think that just as the union of the Divine being and energy is unmerged, so the difference is immutable.

- Anathema to those who accept that every physical possibility and energy of the Divine is a creation.

- Anathema to those who say that if we allow differences in the essence and energy of the Divine, then it means thinking of God as a complex being.

- Anathema to those who think that only the being of God is characterized by the name of God, and not by energy.

- Anathema to those who accept that the being of God can be communicated (i.e. to people), and who do not want to admit that communion is characteristic of grace and energy.

- Eternal memory to His Holiness Metropolitan Gregory Palamas of Thessaloniki, who overthrew the heretics Barlaam and Akindinus, who dared to call the physical and indivisible energy and possibility of the Divine, as well as all the physical properties of the Holy Trinity, created, and also to introduce the doctrine of Platonic ideas and Hellenic myths.

| Cancer with the relics of St. Gregory Palamas. The Thessalonian Council in the name of St. Gregory Palamas. |

The path to monasticism

Saint Gregory Palamas came from a famous aristocratic family (at the end of the 12th century the saint's ancestors moved to Constantinople from the territory of Asia Minor). The approximate date of his birth is considered to be 1296.

Gregory's father, Constantine Palamas, an influential senator, was one of the nobility close to the imperial court. On his deathbed, having repented of his sins, he took monastic vows. After his death in 1301, the reigning emperor, Andronikos II, took his son, Gregory Palamas, under his personal guardianship and protection.

During that period of time, friendly relations began between the orphaned Gregory and Andronikos III, the future emperor, as close as the rules of subordination allowed. Subsequently, Andronik repeatedly provided him with help and assistance.

According to his social status, Gregory received an excellent education. Having the opportunity to study at the Imperial University, he mastered such disciplines as grammar, rhetoric, physics, and logic. Considering the position in society in which Gregory was located, an enviable career could have opened up before him, but he preferred spiritual life to secular well-being.

It is difficult to say when exactly he began to think seriously about monasticism. It is only known that during his studies he had contact with Svyatogorsk monks. This communication affected him in the most positive way: he changed his attitude towards life and rebuilt his behavior pattern.

Quotes

“Just as the separation of the soul from the body is the death of the body, so the separation of God from the soul is the death of the soul. And this is mainly death, the death of the soul. God pointed to it, and when, giving the commandment in paradise, he said to Adam: “On the day you eat from the forbidden tree, you will die” (Genesis 2:17). For then his soul died, having been separated from God through a crime; in body he continued to live from that hour onwards until he was nine hundred and thirty years old.”

“The Apostle Paul said well that “the sorrow of this world makes death” (2 Cor. 7:10). For if the true life of the soul is the divine light that comes from crying for God, as said above in the words of the fathers, then the death of the soul will be the evil darkness that comes upon the soul from the sadness of this world.”

“This is why God created this life for us, to give room for repentance. If this had not happened, then the person who sinned would immediately lose this life. ... Since the time of life is thus the time of repentance, then the very fact that the sinner is still alive serves for him, if he wishes to turn to God, as a guarantee that he will be mercifully accepted by Him. For in real life, autocracy is always in force...everyone always has the opportunity, if they want, to acquire eternal life.”

“Who will not confess grace and give thanks to the Deliverer from death and the Giver of life? – And He also promises to give a reward and an inexpressible reward. “I am”, he says, “I am dead, but I have stomach, and I have more to spare” (John 10:10). What's more? Not only to abide and live by His power, but also to be His brothers and joint heirs. This superfluity is a reward given to those who flow to the life-giving vine and are born on it, who work on themselves and cultivate themselves.”

“After the resurrection of the soul, which is its return to God through the fulfillment of the Divine commandments, the resurrection of the body will follow when it is again united with the soul; This resurrection will be followed by true immortality and co-eternity with God.”

Angelic image

According to various estimates, by the age of 18–20, Gregory, having decided to abandon secular temptations and connect his life with ascetic deeds, went to Athos.

At the same time, he renounced the property inherited from his father and convinced his mother and other family members, as well as some servants, to leave meaningless vanity, renounce the blessings of this world and enter the monasteries of Constantinople.

The emperor looked at Gregory's plan without much joy or sympathy. Either not fully realizing the seriousness of his intentions, or not wanting to lose a loyal and promising subject, he did not want to let Gregory go. But he was persistent and eventually achieved his goal.

On the way to Athos, where Gregory went with two brothers, Theodosius and Macarius, all three stopped on Mount Papikon. By God's providence they spent several months in those places. There is a legend that when Gregory entered into a controversy with the local Bogomils (about prayer), he was almost poisoned.

Having finally reached Athos, Gregory stood under the spiritual guidance of the wise and experienced ascetic, the Monk Nicodemus of Vatopedi. After a two-year test of obedience, monastic difficulties, and temptations, he took monastic vows.

After the blessed death of his mentor, St. Nicodemus, Gregory, with the blessing of his superiors, entered the Lavra of St. Athanasius. The abbot of the monastery assigned him to the singers. In this Lavra, in fasting, obedience and prayer, he labored for three years, and then, guided by the best considerations, retired to the Glossia desert for his labors. Here his spiritual mentor was the famous saint of God, Gregory Drimis.

A couple of years later (around 1325), in order to avoid the consequences of Turkish robbery, Gregory, along with eleven other monks, moved to Thessalonica. From there the brethren planned to move to Jerusalem. But the Lord intervened: the friends were kept in place by the appearance of the patron saint of Thessalonica, the Great Martyr Demetrius.

Priestly ministry

Remaining in place, Gregory, to the joy of the brethren, was awarded the elevation to the rank of priest.

Around 1326 he retired to a mountain located near Verria. There he lived the life of an ascetic, engaged in prayer, devoted himself to labor, vigil and fasting; on Saturdays and Sundays he went out to the local hermits.

The death of his mother prompted Gregory to break his solitude. In 1331 he left for Constantinople. Arriving in the capital, meeting with the sisters - nuns - he had a serious conversation with them, and then, to everyone’s joy, he took them with him to Verria. After some time, the eldest of the sisters, Epicharida, died.

It is likely that even before leaving for the Byzantine capital, Father Gregory met Akindinus, a grammar teacher. There is reason to believe that for some time Father Gregory was his mentor, and that it was he who encouraged him to make a choice in favor of monasticism.

In 1331, Gregory Palamas returned to the Holy Mountain and settled in the desert of St. Sava. During this period he was engaged in writing.

There is evidence that for some time Father Gregory served as abbot at the monastery of Esphigmen.

Prayers

Troparion, tone 8

Lamp of Orthodoxy, / Confirmation of the Church and teacher, / goodness of monks, invincible champion of theologians, / Gregory the wonderworker, Thessalonite praise, / preacher of grace, // praying save our souls.

Troparion, tone 8

Teacher of Orthodoxy, adornment of the saint, / invincible champion of theology, Gregory the miracle worker, / Great praise to Thessaloniki, preacher of grace, // pray to Christ God for the salvation of our souls.

Kontakion, tone 8

Wisdom, the Holy and Divine organ, / of theology the bright trumpet, / we sing to you, Gregory the God-speaker: / but as the mind stands before the mind first, / to Him, instruct our mind, let us call : // Rejoice, preacher of grace.

| St. Gregory Palamas. Icon |

Controversy over Divine Light

In the second half of the 30s of the 14th century, the Orthodox Church was faced with yet another false teaching. Its authorship belonged to Barlaam of Calabria. The immediate reason that pushed him to form the heresy were conversations with the Thessalonian hesychast monks, who testified that during deep concentrated prayer it is possible to contemplate the Divine light.

Varlaam, who had never experienced anything like this (which was quite consistent with the level of his spiritual age), treated these testimonies with distrust and even ridicule. He accused the monks of the heresy of Messalianism, not realizing that he had encroached on the most valuable thing in their ascetic experience: the experience of meetings and communication with God (supporters of Messalianism also contemplated visions, but not of a Divine, but of a demonic nature).

Not limiting himself to criticizing the monks, Varlaam began to criticize some patristic writings. The heated disputes reached the Patriarch, and he, in order to avoid disturbing church order, ordered Varlaam not to bother the monks with his “denunciations.”

In 1337, Gregory Palamas, who arrived in Thessalonica, tried in personal communication to reason with Varlaam and encourage him to renounce blasphemy. But Varlaam did not even think of refusing. On the contrary, he began to express his thoughts in written treatises, wanting to dedicate as many people as possible to them.

The result of the development of this false teaching was the denial of the indisputable fact that in God there are different essences and energies. Since the Divine essence is invisible, and no creature can unite with God in essence, according to the heretics, it turned out that God cannot be contemplated either in the light or in any other way, and that union with Him is impossible in principle. And this despite the fact that union with God in the Kingdom of Heaven is the main subject of Christian hope.

Not wanting to put up with this state of affairs, Father Gregory wrote a number of response essays against the teachings of Varlaam. In these works he proved the rightness of the contemplatives of the Divine Light and exposed the heretic.

In 1341, a Council was held on this occasion in Constantinople. Gregory Palamas, who was present at the Council, revealed and substantiated his point of view. His teaching was recognized as correct, and the teaching of Barlaam was condemned (although he himself was not anathematized).

Soon another Council meeting was held in Constantinople, at which Gregory Akindinus was present. At first, he participated in the heated disputes as a conciliator, but then took Varlaam’s side. At the Council he was present as an accused. Despite his resistance and allegations of violence against conscience, he was convicted.

After these events, Father Gregory remained in the capital for some time. This was due to the difficulties that arose in the sphere of public administration after the death of Andronikos III. In addition to dignitaries, representatives of the highest clergy were drawn into this situation, including Patriarch John Kaleka.

Participation in what was happening did not correspond to the monastic aspirations of Gregory Palamas. At the end of the year, he distanced himself from these political events and retired to the monastery of St. Michael of Sosthenes.

The Patriarch, annoyed by Gregory’s reluctance to support his political ambitions, began to act against the “offender.” As if in revenge, he changed his attitude towards Akindinos and gave him the opportunity to spread the teaching condemned at the Council.

In 1342, John the Cripple convened a Synod against Saint Gregory. This meeting did not have serious consequences, however, the clouds were gathering. A few months later, Gregory Palamas was taken to Constantinople, where he was taken into custody in a monastery. The imprisonment did not last long, and soon the sufferer was transferred to another monastery.

Some time later, Gregory left the monastery. Arriving at the Church of Hagia Sophia, he used it as a more or less safe refuge, remaining there, along with his disciples, for two months. Then the Patriarch nevertheless forced Gregory to leave the temple, after which he was imprisoned in the palace dungeon.

In 1344, the Synod convened by the Patriarch decided to excommunicate Saint Gregory from the Church. This definition was confirmed by the heads of the Jerusalem and Antioch Local Churches.

In the same year, despite the condemnation of Akindinos (in 1341), the Patriarch, to the surprise of many, ordained him to the rank of deacon, and then elevated him to the priesthood. Inspired by high support and belonging to a hierarchical rank, Akindinus began to oppose Gregory Palamas in the fight against heresy with even greater bitterness.

Soon the Patriarch fell under the disgrace of the imperial court, and he was reminded of the consecration of the heretic. In 1347, a Council was held that deposed him from the patriarchal throne. The Council dropped the charges against Gregory Palamas and condemned his ideological opponents. Soon the decision to condemn Akindinus was supported by the authority of the imperial power.

Elected to the patriarchal see, Isidore ordained several bishops from among the supporters of Gregory Palamas, and he himself was elevated to the metropolitan see in Thessalonica.

Life

We know about the exploits and trials that befell the saint from the “Eulogy of St. Gregory,” a kind of hagiography that was written by his contemporary, friend and closest disciple, St. Philotheus (Kokkin), Patriarch of Constantinople, author of many theological texts, prayers, lives, and polemical works. Perhaps he was also a co-author of the final form in the works of St. Gregory Palamas' teaching on hesychia.

Saint Gregory Palamas belongs to the galaxy of the highest minds of the thirteenth century. By birth, he was a Byzantine aristocrat - the first child in the family of Senator Constantine Palamas. Gregory's father was distinguished by his piety, practiced mental prayer, took monastic vows before his death, and shortly before that he prayerfully handed over the children to the Mother of God. After the death of his parent, Gregory’s upbringing was taken over by his highest patron and comrade, Emperor Andronikos II. Young Gregory began to live at the court of Constantinople.

Education

Thanks to his high position, he received an excellent education; at the university, one of his teachers was the famous Greek philosopher and theologian Theodore Metochites.

Useful materials

Gregory was considered the pearl of the imperial palace - he has a high intellect, loves science, and once gave such a brilliant lecture on Aristotle’s categories that he received the highest praise. At the same time, the religious young man, seeking the Lord, was burdened by the secular environment, striving for solitude and prayer. Perhaps, while still in Constantinople, he came into contact with Athonite monks who often visited the imperial chambers.

Gregory begins to practice abstinence, first of all, giving up the luxurious court life.

Departure for Athos

At the age of twenty (according to other sources, eighteen), despite some opposition from his guardian, Emperor Andronikos II, after much persuasion, he leaves the palace. St. Gregory decides to devote himself to God. His departure to Athos, together with his two younger brothers, Macarius and Theodosius, occurs in 1316. He managed to influence the remaining family members and some “smart slaves” who also decided to enter the monasteries of Constantinople. Gregory's mother, Kali (Kallonis), sisters Epicharis and Theodotia take monastic vows.

Upon arrival at the monastery, the young man falls under the command of the Monk Nicodemus, whose cell was located not far from the Vatopedi monastery, where the future saint lived for the next two years, learning to pray, and there he received and was tonsured by his teacher.

On Athos, Gregory indulged in that very ascetic monastic life that he dreamed of at court, he delved into asceticism, and also began to practice “hesychia” (from the Greek - silence, silence), a special kind of prayer and spiritual exercises necessary to achieve internal “silence”, calmness of consciousness from any worldly impressions, preservation of the strong-willed part of the soul from excuses sown by the devil.

Doing Smart

The center of the practice is prayerful “mental doing” (returning or immersing the mind in the heart), - repeated repetition of the prayer text, which may vary slightly, its basis is the “Jesus Prayer”, known to everyone - the invocation of God, the Second Person of the Holy Trinity, the Son of God .

The most common option: “Lord Jesus Christ, Son of God, have mercy on me a sinner.” The constant call, repetition of these words, combined with the practice of sobriety (constant awareness of one’s thoughts and feelings, their control), cleansing the soul and spiritual eyes from sinful thoughts common to fallen man, gradually leads him to the fulfillment of Adam’s destiny - becoming like the Lord, deification , and, ultimately, to the vision of the Uncreated Light of Tabor.

For Orthodox anthropology, mind and reason are completely different concepts. Reason or rationality is a quality that allows one to navigate in worldly existence, make decisions, learn, and experience the world. The mind (or spirit) is a special divine property of the human soul, an organ through which a person can communicate with God. Everyone must go through the path of an active spiritual life in order to purify themselves, especially the most important part of their psyche - the strong-willed and desirable (the one where aspirations, actions are born, where we say “I want, I wish”). The Lord teaches:

“For where your treasure is, there your heart will be also” (Matt. 6:21).

Almost two years St. Gregory managed to live away from the world, the contemplative life he desired, but the time was turbulent for Byzantium, and in 1325, fearing Turkish raids, the holy ascetic with a group of monks was forced to leave Athos.

Philotheus writes that he arrived in Thessalonica, whose patron was the Great Martyr Demetrius of Thessalonica, whose miraculous appearance “kept them in the city.” Here St. Gregory takes the priesthood and gathers a community of hermit monks around the local Church. Around 1326, he made another attempt to retire and moved from the city to Mount Veria, where, according to legend, the Apostle Peter preached. The saint indulges in severe monastic asceticism and the practice of hesychia, going out to the monks only on Saturdays and Sundays to perform divine services.

Around 1330, Stefan Dušan, the Serbian kraal (king), conquered most of Byzantium, which was increasingly turning from an empire into a weak state subject to constant raids. The Serb even calls himself the title of Emperor Romei. Events known as the “Slavic invasion” force St. Gregory will again move to Athos, where he lives in the hermitage of St. Sava, nearby the holy mountain. This place has survived to this day. He is elected abbot of the Efsigmen monastery in the northern part of the Athos isthmus. But his privacy is violated again. The saint enters into perhaps the second most famous controversy in the history of theology.

Controversy with Varlaam

Around the same time, in Constantinople, at the imperial court, a new, very difficult personality appeared, a Greek of southern Italian origin, like Palamas, who had excellent command of the powerful apparatus of ancient philosophy. He belonged to the Order of Basil the Great, apparently was a Uniate, his name was Barlaam the Calabrian (came from the province of Calabria), thanks to his intelligence and erudition, he quickly found access to the domestic (viceroy) of Emperor Andronicus III, John Cantacuzene, mentored his children, and often visited palace

Interesting fact

Apparently, Varlaam hid his Uniate roots, he demonstratively entered into theological debates with representatives of Rome, even wrote several treatises refuting the Catholic teaching about the “filioque” (the hypostatic properties of the Trinity, the procession of the Holy Spirit not only from the Father, but also from the Son).

Saint Gregory, of course, read them; at the same time he created his “Propaedeutic Chapters” - also in refutation of the Latin dogma. A theological clash arises: Western rationalism, scholasticism, which, in general, had a good background - the defense of dogmas with the help of reason and logic. However, the Catholic enthusiasm for scholasticism made it the main principle of Western theology, while forgetting about the revealed nature of dogma. St. spoke out against this approach. Gregory Palamas.

In his work “Triads in Defense of the Sacredly Silent,” he postulates that dogma cannot be proven by the arguments of reason, “for it is the revelation of God.” He writes his creations in full accordance with the patristic tradition - the teachings of the Cappadocians.

At the same time, Varlaam becomes acquainted with monastic hesychast practices. Of course, as a scientist and rationalist, he subjects them to criticism and even ridicule.

Thus, the initial dispute arose due to the saint’s refutation of Barlaam’s ideas regarding issues of knowledge of God. The Italian philosopher professed a rather strict rational approach to knowledge; his theories were based more on the arguments of human logic than on experience. In particular, he believed that God is incomprehensible, judgments about Him are unprovable, therefore, it is impossible to know exactly what relationships occur between the Persons of the Holy Trinity. It was this peculiar agnosticism that St. analyzed. Grigory.

This was followed by an accusation of heresy, but this time from Varlaam, who, being familiar with the teaching of “mental prayer,” found it unorthodox. According to the Calabrian, the vision of the Light of Tabor, and the entire teaching about it, was the product of a state of delusion, self-delusion. He admitted the possibility that the Gospel story about the Light that transformed the Lord on Mount Tabor was in this part of a symbolic nature.

It must be said that hesychia is a fairly ancient, but spontaneous practice for monastics, and St. Gregory Palamas streamlined and substantiated it, giving it the appearance of a doctrine.

The Athonite hesychast (silent) monks, shocked by Varlaam’s attacks, turned for help to the saint, who practiced this type of prayer; he, of course, stood up for his brothers. He writes the essay “Triads in Defense of the Sacredly Silent” as a theological treatise, directed not only against the rationalistic scholasticism of Varlaam. Palamas creates the key doctrine for Christian soteriology - about human salvation. Its main, dogmatic part can be reduced to three points:

- The non-participation of God in essence and the participation in energies. The Being of God is incomprehensible and invisible.

- The light that the Lord’s chosen disciples saw on Mount Tabor was not symbolic, but real—uncreated and energetic. This is God Himself.

- It is possible to comprehend and commune with the energies of God through transformed human feelings.

14

November

1359

After a long illness, Saint Gregory died at the age of 63 (or 61). His last words were: “To the heights!”

Saintly activity

Saint Gregory arrived in Thessalonica only a few years later, after the suppression of the rebellious unrest that flared up there and the restoration of proper administrative order.

Meanwhile, in the highest circles of the clergy, dissatisfaction was brewing with the installation of Isidore to the Patriarchal See and the rehabilitation of Gregory Palamas. Accusations began to fall on the saint again.

As a precaution, the opposition distanced itself from Akindina, but did not abandon his false ideas. Controversy broke out again. This time, the role of the leading polemicist on the part of the opponents of Gregory Palamas went to Nikifor Grigora. He composed a rather harsh essay against the saint, but the saint skillfully exposed his arguments.

In 1351, another Council was convened, confirming the orthodoxy of Gregory Palamas. The result of the work of the Council was the final approval of the dogmatic teaching about the difference in God's essence and energies, about the uncreated origin of the Divine light; signed by Patriarch Callistos of Constantinople and (then metropolitans) Gregory Palamas and Philotheus Kokkin “Conciliar Tomos against like-minded people Varlaam and Akindinus.” The “Synodik of the Triumph of Orthodoxy” was also replenished.

In the autumn of the same year, Gregory Palamas reached his department, but did not rule it for long. Contributing to the settlement of the internal political struggle that had broken out, he left for Constantinople. Along the way, he and those accompanying him were captured by the Turks. He remained in captivity for several months (according to some sources, about a year) until he was released for a ransom.

In the period from 1355 to 1357, Saint Gregory was engaged in affairs in the diocese entrusted to him. It is reported that through his prayers God performed healings.

The blessed death of the saint occurred on November 14, 1357 (according to other sources, 1359), when he was 63 years old. His glorification took place in 1368, less than ten years after his death.

History of the relics of the saint

The saint died on November 14, 1357 (or 1359) in Thessalonica, with the rank of metropolitan. He was buried in the Hagia Sophia. When the Byzantine Empire was captured by the Ottoman Turks (1523), the Orthodox church was turned into a mosque. The relics of the saint were transferred to the Vlatadon Monastery (Thessaloniki), from where they were soon moved to the city cathedral.

In 1890, there was a fire in the cathedral, but the relics of the saint were not damaged by the fire. The relics found rest in the restored cathedral, which was consecrated in his honor in 1914.

Finding

After his death, the body of the saint was laid in the Cathedral of Hagia Sophia in Thessaloniki. The miraculous power of the relics of Gregory Palamas manifested itself immediately, which was reflected in the Eulogy on the life of the saint, compiled by Patriarch Philotheus Kokkin of Constantinople.

Current location

Particles of the saint’s relics, in addition to the cathedrals in Thessalonica, are kept in the monasteries of Athos:

- Esphigmensky;

- Xenophon;

- St. Dionysius;

- Great Martyr Panteleimon.

You can venerate the holy relics of Gregory Palamas in the Lavra of St. Sava the Sanctified in Israel.

Miraculous power

During the life of Gregory Palamas, it was known that through his prayer God healed the suffering. The messages date back to 1355-1357. After the death of the Metropolitan, the miraculous power did not disappear. People began to receive relief from illnesses after praying and touching the silver shrine where Palamas’ remains rested. The fame of the power of the holy relics reached the Patriarch of Constantinople Callista I, who made a request for miraculous healings.

Creative heritage

Saint Gregory left an extensive legacy for the edification of believers. He is rightly considered a theologian of the uncreated light. Meanwhile, the palette of his works is much more extensive. Traditionally they are divided into the following groups.

Dogmatic-polemical: Svyatogorsk tomos in defense of the sacredly silent, Treatise [On the fact that] Varlaam and Akindinus truly impiously and godlessly divide the one Divinity into two unequal deities, Triads in defense of the sacredly silent, On Divine energies and their communion, On Divine union and division, Confession of the Orthodox Faith, Interview of the Orthodox with the Barlaamites, Antirrhetics against Akindinus, One hundred and fifty chapters devoted to questions of natural science, theology and morality, Interview of the Orthodox Theophan with Theotimos, who returned from the Barlaamites, On the Divine and deifying Communion, or on Divine and supernatural simplicity, Dispute with Chions, Omilia, etc.

Moral and ascetic: Explanation of the Ten Commandments, About the fact that all Christians in general should pray unceasingly, To Xenia about the passions and virtues, Decalogue on the Christian Law, Word on the Life of St. Peter of Athos, Reply to Pavel Asen, etc.

Letters: Letter to his Church, Letter to Akindinus, sent from Thessalonica before the conciliar condemnation of Varlaam and Akindinus, etc.

Prayers: Prayer to the Most Holy Theotokos.

Prayer

O truly blessed and honorable and most beloved head, the power of silence, the glory of monastics, the common adornment of theologians and fathers and teachers, the apostles' companions, confessors and martyrs, the bloodless zealot and crowner of words and deeds and piety, the champion and chosen commander of divine dogmas, the high expounder and teacher, the delights of various heresies to the consumer, the representative, guardian, and deliverer of the whole Church of Christ! You have reposed in Christ, and now you watch over your flock and the whole Church from above, healing various diseases and governing all your words, and driving out heresies, and delivering manifold passions. Accept our this prayer and deliver us from passions and temptations, and worries, and troubles, and grant us weakness and peace and prosperity, in Christ Jesus our Lord, to Him be glory and power, together with His beginningless Father and the Life-giving Spirit, now and ever and ever. Amen.

Prayer to Saint Gregory Palamas, Archbishop of Thessalonica

Oh, all-praiseworthy saint of Christ and wonderworker Gregory! Accept this small prayer from us sinners who come running to you and with your warm intercession beg the Lord our God Jesus Christ, that, having looked upon us mercifully, He will grant us forgiveness of our voluntary and involuntary sins, and by His great mercy He will deliver us from troubles, sorrows, sorrows and illnesses, mental and physical, that beset us; May the land bear fruit and everything that is needed for the benefit of our present life; May He grant us the end of this temporary life in repentance, and may He grant us sinners and unworthy of His Heavenly Kingdom to glorify His endless mercy with all the saints, with His Beginningless Father and His Holy and Life-giving Spirit, forever and ever. Amen.