At the turn of the 15th-16th centuries, serious problems arose in Russian Orthodoxy, which resulted in a confrontation between two religious and political groups, known under the names “non-covetous” and “Josephites.”

Between representatives of these branches of Russian Orthodoxy, a tough half-century discussion broke out about the right of monastics to own land and property in general, as well as about ways to combat heretics, of which there were more and more in Russia.

Dates, causes and consequences of occurrence

1479 – Joseph Volotsky founded his own Joseph-Volokolamsk monastery. The abbot received monks from other monasteries into his monastery. He also received the hungry, giving them bread. This same monastery was the starting point for future Josephites.

The reasons for the emergence of the church-political movement of the Josephites are two main factors:

- The emergence of the Judaizer heresy in Novgorod in 1470;

- The desire of Tsar Ivan III to limit or completely eliminate church land ownership.

The consequence of the struggle of the Josephites with the heretics (Judaizers) was the convening of the Council in 1504, where they were cursed (anathematized).

In the same 1504, at the Council, Ivan III Vasilyevich changed his point of view and supported the Josephites.

Cathedral of 1503

Unlike Nil (Maikov), whose ideal was a small group of prayer books united around a confessor on the basis of brotherly love, the monastery of Joseph (Sanin) was a disciplined detachment of spiritual warriors who fight sin under the leadership of the abbot. Joseph Volotsky did not consider the concentration of material wealth in the monastery a vice, believing that, subject to personal monastic asceticism, they help strengthen the authority of the church.

An open dispute between representatives of the two movements took place at the Council of 1503. Both the first and the second agreed in condemning personal money-grubbing in the church environment. At the same time, the “non-acquisitive” called on the monasteries to give up all property and lands and transfer them to the state treasury.

Supporters of the “acquisitors” defended the right to monastic property, arguing that a rich church could perform charitable functions in society, and also, if necessary, support state power. In essence, Joseph Volotsky was a man of statesmanship who believed that it would be useful to organize the entire Russian economy according to the church-monastic model.

Andrey Shishkin “Before the service”

Activities of the Josephites

The activities of the followers of St. Joseph were carried out in several directions. The main directions were the following:

- As abbots they served in the monastery of the Monastery of St. Joseph;

- They were abbots in a number of large Russian monasteries;

- They worked in the bishop's departments.

The internal routine of the Joseph-Volokolamsk Monastery was aimed at order and unity among the monks. All this, along with high standards of teaching, as well as corporate solidarity, contributed to the fact that people from this monastery, who occupied high spiritual positions, actively promoted graduates of the Joseph-Volokolamsk Monastery.

In the second half of the 16th century, the monastery took 19th place in terms of influence in Rus', according to the “Ladder of Spiritual Authorities”. Josephite abbots played an important role in church and zemstvo councils.

Examples:

- 1566 - signing, among other clergy, by Abbot Lawrence of a conciliar verdict on the continuation of the Livonian War;

- 1587 - Abbot Levkiy, among others, signed a letter of ascension to the throne of Boris Godunov;

- 1613 - Hegumen Arseny, among others, signed a letter of ascension to the throne of Mikhail Fedorovich Romanov.

The monastic monastery monastery's monks were frequent guests at the residence of the Tsar, as well as John IV Vasilyevich during his military campaigns.

According to the 1522 charter of Vasily III Ioannovich, matters related to the Joseph-Volokolamsk Monastery could be judged exclusively by the Grand Duke. This decree was canceled by Stoglav in 1551.

The charter of 1556 indicates that jurisdiction now belongs to the Volokolamsk brethren to the Moscow Metropolitan, His Holiness Macarius. In 1563 to the Archbishop of Novgorod. In 1578 to the royal court.

Throughout the 16th century, state authorities and the church sought to make studying at the Joseph-Volokolamsk Monastery a mandatory career step to the rank of abbot and archimandrite in many Russian monasteries.

The Josephites reached their highest point of influence in the period from 1542 to 1563. At this time, the position of metropolitan was held by Macarius, who revered the Monk Joseph of Volotsk.

By 1551, when the Council of the Hundred Heads was convened, people from the Joseph-Volokolamsk Monastery occupied 5 of the 10 posts of bishops' departments.

Ideology of movements

The ideological credo of the Josephites and the “Trans-Volga elders” was significantly different.

For the spiritual leader of the “elders” Nil Sorsky, faith in the Lord was an exclusively personal matter for each believer, because everything important happens not in the material world, but in the soul. Hence the call to non-covetousness as a way to achieve complete inner freedom for impeccable service to God.

The “Trans-Volga elders,” including Maxim the Greek and Vassian, did not recognize the nationalization of the Church, reducing the role of monasticism to:

- the ceaseless struggle for the soul of man;

- prayers for the flock and clergy.

Managing the lands and the laity is the task of earthly rulers. In the first years of the reign of Ivan IV, this concept was approved on his part, and in the closest circle of Grozny, the “Chosen Rada,” the main roles were played by priest Sylvester, boyar Adashev and Prince Kurbsky, who sympathized with the views of the Nile.

At the turn of the 15th-16th centuries, the Josephites had difficulty finding agreement with Ivan III, who in those years was more inclined to listen to Elder Nile and was hatching plans to return monastic landholdings to the state.

Dissatisfied with the possibility of secularization, as well as with the condescending attitude of the Grand Duke towards heretical “Judaizers”, for example, towards his close associates, clerk Fyodor Kuritsyn and Archpriest Alexei, Joseph created a theory according to which the ruler is, first of all, a man, although appointed to “divine service” .

In his work “The Enlightener,” Volotsky pointed out that a worldly prince may make mistakes that could destroy not only the ruler himself, but also all his subjects. According to Josephus, which was later modified, a secular ruler should be revered; but princes have power only over the body, and they should be obeyed “bodily, not mentally.”

In addition, at that time Joseph believed that spiritual power was higher than secular power, and the church needed to “worship more” than the sovereign.

Nevertheless, the Josephites, based on the postulate of the responsibility of the worldly ruler for the inhabitants of his state before the Lord, saw his prerogative in caring for both the temporal and spiritual care of people, the protection of the true faith, and the protection of his subjects, including from the influence of heretics. Heretics corrupt the souls of people, and, therefore, are worse than robbers who encroach only on the “body”; This means that they need to be “burned and hanged,” as Archbishop Gennady of Novgorod put it.

Over time, the views of the Josephites on the relationship in the triad “Church - government - people” underwent changes, and they began to consider the position of worldly power not lower, but on an equal footing with church power. Joseph's followers proclaimed that it was a sin to disobey a worldly ruler, and even called for them to serve him as a Lord rather than as a man.

Non-acquisitive people recognized the idea of the government’s responsibility to the people, believing that the duty of the government is to “judge and protect.” For them, a real ruler chosen by God must be aware of his highest responsibility to the Lord and people, and observe moral principles in accordance with his status as God’s anointed.

On the contrary, according to the teachings of the Josephites, rulers are not just chosen by Heaven, they themselves are almost sacred personalities.

Therefore, their ideas were liked by the Russian princes and tsars to such an extent that they abandoned the gigantic land holdings of the church, receiving in return inaccessibility to control public institutions, that is, they became absolute monarchs.

Already under Ivan the Terrible, a discussion began on the issue of books. Being supporters of printed books that appeared in Rus' at that time, the non-covetous people pointed out a lot of mistakes made by copyists, which led to discord and “disorder” in church service and worldly life.

The Josephites perceived printing as another “Latin” heresy, arguing that for ordinary people “the honor of the Apostle and the Gospel” was a sin.

Josephites and non-possessors

The Josephites waged an irreconcilable war with the so-called non-covetous people. Their movement was led by Nil Sorsky. The position of the non-acquisitive people was a return to the period of primitive Christianity, which was expressed in the position of collectivism and asceticism. This led to the abandonment of monastery property.

Initially, Tsar Ivan III Vasilyevich supported the non-covetous people, but in 1504 he changed his position. The Council of 1504 passed a resolution condemning the Judaizers and anathematized them.

Who has won?

Formally, at the council of 1503, the model proposed by Joseph Volotsky was adopted. However, considering the process in historical development, one can evaluate it somewhat differently. There is an opinion that both Nil Sorsky and Joseph Volotsky lost. Neil died five years after the completion of the cathedral, and the monasteries he founded were destroyed. Joseph survived him by seven years, and spent his last years in disgrace with Tsar Vasily III.

The truly victorious were the followers of the Volokolamsk abbot, the so-called Josephites, who began to use the monastic wealth not for the benefit of Russia and the church, but for their own purposes.

In 1551, the Council of the Hundred Heads took place, which was possible without the Nile, and without Joseph, and without Vasily III, whose place was taken by the young Ivan the Terrible. As a result of the decisions taken there, the church's holdings almost doubled and began to account for almost a third of state revenues.

Andrey Shishkin “Tsar Ivan”

Joseph Volotsky

Joseph Volotsky, real name Ivan Sanin. Born in 1440 into a noble family.

At the age of 20, he became a monk and went to the monastery of Paphnutius Borovsky. The monastery was distinguished by great wealth. Stayed there for 18 years.

After the death of Paphnutius in 1477, he was appointed abbot. However, he quickly resigned from this post due to serious disagreements with the spiritual brethren.

In 1479 he founded his own Joseph-Volokolamsk monastery, which from the first days was under the protectorate of the appanage prince Boris Volotsky.

Joseph Volotsky was an active supporter of land ownership by monasteries, the need to decorate churches with paintings, as well as rich iconostases and images. He was an irreconcilable enemy of the Judaizers and demanded their death penalty.

At the end of the 15th - beginning of the 16th centuries. The authority of the Joseph-Volokolamsk monastery reached such significance that famous missionaries, preachers, publicists and church hierarchs came from its monastery. In the middle of the 16th century, representatives and people from the monastery began to be called “Josephites.”

Many did not like the views of the Monk Joseph. He was criticized from a position of mercy and non-covetousness. The elder himself was called “the teacher of lawlessness,” “the lawbreaker,” and “the Antichrist.”

The Monk Joseph died on September 9, 1515 after a long, serious illness.

About spiritual “comrades” - St. Joseph of Volotsky and Nil of Sorsky

Saint Reverend Joseph of Volotsky. Icon painting workshop of Ekaterina Ilyinskaya

The Monk Joseph (in the world Ioann Sanin; 1439/40–1515) already at the age of eight was sent by his parents for education and spiritual education to the Holy Cross Monastery in the town of Volok on Lama. At the age of twelve he was returned home, but soon he secretly went first to the desert near Tver, and then, on the advice of an experienced elder, he moved to the Monk Paphnutius of Borovsky, then known for his spiritual strictness, who tonsured him as a monk in 1460.

On his monastic path, Joseph initially showed himself to be a firm monk, prone to emphasized statutory piety and a consistently ascetic monk.

However, with all his inner concentration on monastic asceticism, Joseph was by no means deprived of a living human feeling of love for his neighbors, the manifestation of which in all aspects of Christian life he always recognized as a personal moral duty. First of all, it is in this that one should look for the origins of his constant aspiration, following the Monk Paphnutius, towards public service - to help the orphaned, the poor, the sick, or the peasants who were starving during crop failures.

And what is not at all typical for monks, who most often sought to completely cut off all their ties with their past, worldly life, including with family and friends, the Monk Joseph, judging by his “life,” for some time was clearly tormented by thoughts about his lonely and old age helpless parents. In the end, unable to bear this mental anxiety, he turned to the Monk Paphnutius for advice. He, seeing that his student had “great zeal according to God and a strong and unshakable mind” and that “his mother’s love does not harm him” - as was usually the case with “those who are weak” - “commanded him to take care of them, for the sake of old age and weakness, he ordered his father to take him to the monastery”[1]. As a result, Joseph’s mother, on his advice, accepted monasticism in the neighboring Vlasievsky monastery, and he took his father to his cell, tonsured him as a monk with the name Ioannikiy and looked after him, “feeding him with his own hand,” since he was “in great weakness and in the weakening of the arms and legs”[2]. Joseph became for his father an elder, a teacher, a servant, and a “support,” “comforting from despondency, honoring the Divine Scriptures”[3].

As one of the compilers of the Volokolamsk Patericon, an elderly parent, recalls with gratitude to the “verb” Joseph: “What will I repay you, child, God will repay you for the sake of your labors; “I am not your father, but you are my father, both in the physical and in the spiritual.”[4] In a modest monastic cell one could see with one’s own eyes “the fulfillment of God’s love: the son working, and the father helping with tears and prayer. And so she lived for 15 years, serving her father, and the elders (that is, the Monk Paphnutius. - Dr. G.M.

) without breaking our word

in

everything”[5].

Observing Joseph’s hard work and real manifestations of his love and obedience, Paphnutius once remarked: “...this one will build his own monastery after us, no less than ours”[6].

In a similar way, Joseph remained in obedience to the elder Paphnutius for 18 years. Before his death, the elder commanded the brethren “to ask the sovereign sovereign for elder Joseph to become abbess”[7]. Grand Duke Ivan III granted the monks' request.

So Joseph became the abbot of the Borovsky monastery. In an effort to establish a communal life there, he soon visited the Kirillo-Belozersky monastery to familiarize himself with the strict “dormitory” regulations in force there. And yet, Joseph failed to introduce the Cyril Rule in the Borovsky Monastery: many monks wanted to live here “especially.” Then in 1479, near Volokolamsk, as if fulfilling the prediction of the Monk Paphnutius, he founded his own monastery - similar to Belozerskaya - with a wooden church in honor of the Dormition of the Mother of God.

Over time, the Joseph-Volotsky Monastery became exemplary not only spiritually, but also culturally, gradually turning into a kind of church academy of that time: books and chronicles were copied here, icons were painted, and the local library was considered one of the richest in Rus'. In 1485–1487, Joseph erected a white-stone Assumption Cathedral in the monastery, which, unfortunately, has not survived; in its place now stands an elegant cathedral from the late 17th century[8].

The monastery was patronized by the local prince, the Grand Duke of Moscow, and Archbishop Gennady of Novgorod († 1505), since the appanage Volokolamsk was then still subordinate to the Novgorod saints. All this contributed not only to the further establishment of normal monastic life in the monastery and its relatively calm and orderly course, but also helped its economic prosperity. The latter made it possible for the Volotsk abbot to pay special attention to Christian charity. As mentioned above, in lean years, the Monk Joseph invariably, continuing the tradition of Elder Paphnutius, helped the hungry: up to 600–700 people were fed daily in the monastery refectory.

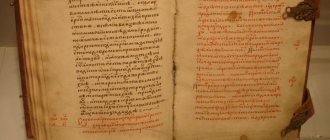

The Monk Joseph was distinguished not only by his unusually strong-willed character and sober, practical mind, but also by his penchant for “book wisdom,” due to which he often amazed his listeners with his great erudition for those times. As Dosifei Toporkov, the author of the funeral eulogy dedicated to the Volotsk ascetic, says, Joseph “kept the Holy Scripture in memory at the edge of his tongue”[9], which was especially evident in his sermons and when writing his own literary and theological works. The monk entered the history of ancient Russian religious thought as the author of the famous “Enlightener” [10] - a book in the genre of words, dedicated mainly to denouncing the so-called “heresy of the Judaizers” that spread at the turn of the 15th–16th centuries in Novgorod and Moscow (that is, taking into account the then vocabulary and, in modern language, “Judaizers”).

The adherents of this movement recognized only the Old Testament part of the Bible, in accordance with the doctrine of Judaism, rejecting the entire system of Christian New Testament values: the Gospel teaching about God the Trinity, the Church itself, the priesthood, divine services, church sacraments and icons. They replaced true knowledge of God with the “evil zodia” - astrology.

Not only did the heretics (at times, albeit rightly denouncing the individual vices of some unworthy Christians) corrupted ancient Russian society as a whole, sweeping aside the inner truth of the Christian worldview, at the same time they also allowed unprecedented blasphemy, cynically trampling on the religious shrines of the people.

According to literary sources, “the Novgorod heretics not only destroyed crosses and icons, but invented various ways to insult these sacred objects: they bit them, threw them into bad places, slept on icons and washed on them, doused them with sewage, tied crosses on the tails of crows.” [eleven]. After some time, the heresy penetrated into Moscow, receiving a certain amount of support there even at the court of the Grand Duke. Moreover, the then Metropolitan of Moscow Zosima began to secretly profess this heretical teaching, until in the end he was convicted of unorthodoxy, deprived of the priesthood, “like a vicious wolf.”

The people's living sense of reverence for the holiness of Orthodoxy was deeply wounded and humiliated by all this, and therefore it is understandable that in those very tough times, society dealt with heretics quite harshly. After their condemnation by the Moscow Council of 1503, some of them were even executed.

In the “ideological-theoretical” and theological sense, the heresy was completely destroyed precisely on the pages of “The Enlightener,” where the Monk Joseph examined in detail the main errors of the Judaizers and answered many of the questions of a purely theological nature that arose among them.

He was constantly supported in the fight against heretics by Archbishop Gennady of Novgorod, also a fairly enlightened monk for his time, known to us as the compiler of the complete Russian copy of the so-called Gennadian Bible, whose text subsequently formed the basis of the printed Ostrog Bible (1581) by the famous “pioneer” printer. Ivan Fedorov.

"The Enlightener" St. Joseph Volotsky. Handwritten book pages

Joseph’s “Enlightener” also entered the history of Orthodox culture - as the first attempt in the theology of Ancient Rus' to systematize for the domestic reader the Orthodox teaching about the icon and the veneration of holy objects: in this book Joseph included the famous “Message to the Icon Painter” (in three Words about the veneration of holy icons) [12].

Simultaneously with his denunciation of the adherents of the Novgorod-Moscow heresy, the Monk Joseph expressed in the “Illuminator” (in his seventh word) his basic life principles, in which he was raised by the elder Paphnutius and which reflected the ideal spiritual image of a Christian in general - as it was understood then in Rus' .

Here are some of the simple and clear lines of the Volotsk ascetic: “Be righteous, wise, comforter of the sad, feeder of the poor, receiver of strangers, champion of the offended, tender to God, friendly to people, patient in adversity, unkind, generous, merciful, sweet in answers, meek, do not strive for glory, be unhypocritical, child of the Gospel... not loving gold... be humble, bowing down, stretching your mind to heaven... speak little, and think more... work with your hands, give thanks for everything, endure in sorrows, have humility towards everyone, protect heart from evil thoughts, do not test the life of the lazy, but be jealous of the life of the saints... turn away from the human heretic... When talking with a beggar, do not offend him...” [13] Or: “To everyone created in the image of God, do not be ashamed to worship your head, do not honor your elder be lazy and try to put his old age to rest, meet your peers peacefully, accept your lesser ones with love... have quiet havens, monasteries and houses of saints, resort to them, grieve with them, comfort them in poverty; If you have anything you need in your house, bring it to them, for you put it all in the hand of God.”[14]

Of course, all these teachings did not remain just abstract didactics for Joseph himself - similar traits of a spiritually harmonious human personality may well be applied to himself - let us at least remember his Christian attitude towards his own parents.

Being politically a supporter of the strong autocratic power of the Moscow princes, Joseph at the same time sought to strengthen the independence of the Church, one of the necessary conditions for which was its economic independence. Therefore, unlike the famous “Trans-Volga” elders, he consistently advocated for the possibility of church monasteries owning their own villages and land, which was quite natural for the medieval economic system.

If the “trans-Volga residents” of that time, led by another great ascetic, the Venerable Nil of Sorsky (1433–1508), preferred to lead a quiet hermit life in small northern hermitages, trying to avoid unnecessary economic worries, then the supporters of the Venerable Joseph sought an active social role for monasteries - to implementation of large social assistance programs, and active educational activities. The disciples and followers of the Volotsk abbot were more drawn to the broadest strata of ancient Russian society, to the “world”, for which, to the best of their ability, they tried to become a Christian light.

Life in the monastery of St. Joseph was incredibly difficult. As one of the famous Russian bishop-preachers of the second half of the 20th century, Metropolitan Anthony (Bloom), characterized it at one time, “the monastery, where about a thousand monks lived, was located in a cold region, but was never heated. Monks were not allowed to wear anything other than a hair shirt and a robe thrown over it. Daily worship lasted ten hours, and work in the fields or in the monastery took seven to eight hours. Sometimes they grumbled and complained: “We are starving, although our granaries are full... and you do not let us eat; we are thirsty and we have water, but you do not allow us to drink.” Their holy and stern abbot answered: “You do not work to satisfy your needs, not to ensure an easy life for yourself; you should not live in warmth, in peace. Look at the surrounding peasants: they are hungry - we must work for them; they endure the cold - we must prepare firewood for them; Among them there are many orphans - you arrange a shelter for them; they are ignorant - for them you keep a school; Their old people are homeless - you must maintain an almshouse for them.” And this unfortunate thousand monks, some of whom strived with all their might for holiness, grumbled and grumbled... And yet, under the strong hand of their abbot, they led a life that was all love. It happened that they rebelled when the flesh could not stand it, but among them there was their conscience - the Monk Joseph, who did not allow them to fall as low as they were ready to fall. In more modern terms, he could be said to be a collective “super-ego.” He stood among them with his absolute demands... And if you read the works and life of the Monk Joseph, you will undoubtedly see that there was nothing there but love, because he did not care about anything else. He didn’t care about the consequences, it didn’t matter what people thought about his “crazy” practices. He only said that these people are hungry and need help, and we, who know Christ, who know who He is, must bring Him to these people. If you have to lay down your life for this, well, you will lay down your life! In his writings you will find only rare words about the rest that awaits the monks and many more places where the monks are warned: if they do not work as hard as they can, hellfire awaits them! "[15]

Over time, unfortunately, the high moral pathos, so inherent in Joseph himself and so clearly expressed in his desire to “enlighten” everyone and help everyone, turned out to be somewhat reduced in the circle of his later followers (the so-called Josephites), for whom monastic possessions sometimes began to mean much more than they deserved. This sometimes seemed to cast - completely unfairly - a certain “worldly” shadow on the effectively living, sincere, invariably disinterested and spiritually sublime image of the Monk Joseph. To some extent, this was due to ordinary human weakness, which was completely alien to the

to the Volotsk abbot: “Joseph’s truth,” while remaining itself, only significantly, alas, “dimmed due to the cowardice and pliability of his successors”[16].

***

Venerable Neil of Sorsky

No less than the Venerable Joseph of Volotsky, a pupil of the Kirillo-Belozersk monastery, the already mentioned Venerable Nil of Sorsky, from the Moscow boyar family of the Maykovs, is also known in the history of Russian monasticism of that time.

He had a fairly good education and was a copyist of books in the monastery for some time. With the blessing of the wise elder Paisius Yaroslavov, Nil, together with his constant “fellow”, the boyar’s son, monk Innocent (Okhlyabenin), left Kirillov for Athos. Here, as well as in the monasteries of Constantinople, he spent several years, mastering to finesse “the path of internal purification and unceasing prayer performed with the mind in the heart,” sometimes achieving in it the highest “luminous insights” of the Holy Spirit[17]. In other words, he brought to Rus' an experienced knowledge of the highest degree of hesychast “monastic work”, that is, a “silent”, contemplative and prayerful state of the soul - as a permanent way of life of a real mystic monk.

Returning to the Belozersky monastery, Nil, however, did not stay in it for long and soon built a chapel and a cell 15 versts from it in the forest, on the swampy river Sora, and then - with the monks who joined him - he cut down the wooden Sretenskaya Church here, creating gradually another modest desert-dwelling northern monastery. In it, the Monk Nil continued his monastic feat - “as a spiritual man in word, life and reasoning” [18] - according to the strictest monastic rules, which demanded an extremely solitary, hermitic life in labor, in complete rejection of earthly goods, in complete rejection of any forms ownership of any property or land.

Nowhere, perhaps, in Rus' were church services performed with such completeness, rigor and a fiery spirit of prayer as in the wretched monastery of St. Nile. In contrast to the also rather harsh “dormitory” rules of St. Joseph, two guides to spiritual life compiled by Neil - “Tradition to his disciples about living in the monastery” and “The monastery rules” - are more aimed at the internal improvement of the human personality; they are also characterized by

greater development of the teaching about the ways for a monk to achieve the grace-filled state of his soul, completely rooted in Christ. The writings of the great teacher of monastic asceticism that have reached us still represent a precious guide for monastics; they, moreover, are significant monuments of ancient Russian teaching literature.

In the first four chapters of the “Charter” (there are 11 in total), St. Neil “speaks generally about the essence of internal asceticism or about our internal struggle with thoughts and passions and how to conduct this struggle, how to strengthen ourselves in it, how to achieve victory. In the fifth chapter, the most important and extensive, he shows, in particular, how to wage an internal battle against each of the eight sinful thoughts and passions from which all others are born, namely: against gluttony, against the thought of fornication, against the passion of the love of money, against the passion of anger. , against the spirit of sadness, against the spirit of despondency, against the passion of vanity, against proud thoughts. In the remaining six chapters, he sets out the general means necessary for the successful conduct of spiritual warfare, which are: prayer to God and calling on His holy name, remembrance of death and the Last Judgment, internal contrition and tears, protecting oneself from evil thoughts, removing oneself from all cares , silence and, finally, observing a decent time and manner for each of the listed activities and actions”[19].

If the Monk Joseph sought, as already noted, to give monasticism itself, preferably the greatest social significance - and therefore his ideal of church life was the widespread creation of large, economically organized and influential “coenobitic” monasteries with almost military order and discipline, then the Monk Nil leaned toward a different type monastic life - skete - and turned primarily to the other side of the monastic, as they said in the old days, “doing”: he was an adherent of a more intellectually meaningful and prayerful and contemplative hesychast practice of a purely personal, desert (or at least semi-desert) monastic “feat”. To accomplish this kind of feat, as Neil believed, is much more convenient in the conditions of a very small monastic community-skete - with three or four monks, including an experienced elder leader. Only in this case was ensured, in his opinion, a more careful and attentive personal approach of the elder to each student during spiritual education and teaching him the “art of arts” - the constant “creation” of the Jesus Prayer.

Entering into the struggle with the enemy of salvation, go alone, still inexperienced, a monk into the desert prayer silence - “here and

yu" is extremely dangerous and spiritually harmful. This has long been known from the history of Orthodox monasticism, and therefore Neil strongly pointed out in his “Charter” (we present here an excerpt from it - not only as evidence of the spiritual and pedagogical experience of the great elder, but also as a generally characteristic example of ancient Russian teaching literature in the field of Christian asceticism ):

“It is extremely dangerous for a warrior unskilled in single combat to separate from his numerous militia in order to take up arms against the enemy alone; It is extremely dangerous for a monk to enter into silence before he has gained experience and knows his spiritual passions: he perishes physically, this one - spiritually. For the path of true silence is the path of the wise and those only who have acquired Divine consolation in this difficult feat and help from above during times of internal warfare.

Whoever wants to retire into silence ahead of time, the common enemy will prepare for him much more confusion than peace, and will bring him to the point where he says: It would be better for me not to have been born.

The reason for this collapse is the height and inaccessibility of mental prayer.

Remembrance of God, that is, mental prayer, is above all else in monastic activity, just as the love of God is the head of all virtues. And the one who shamelessly and boldly strives to come to God in order to converse with Him and purely infuse Him into himself with compulsion, he, I say, from the demons, if allowed, is caught in death, because proudly and boldly rushes to the heights ahead of time this. Only the strong and perfect are able to privately confront demons and draw the sword against them, which is the word of God...

Those who struggle with carnal passions can go into a solitary life, and not just as it happens, but in due time and with the guidance of a mentor - for solitude requires angelic strength. Let those who are chilled by spiritual passions not even dare to see traces of silence, lest they fall into frenzy.”[20]

A wise elder “schoolmaster” (this is how the Greek word “teacher” is translated) to Christ, leading his few spiritual children on the path to salvation, their common, constantly deep in prayer, outwardly meager life without any worldly blessings - all this could well exist and in the farthest hermitage-hermitage. And in such difficult conditions, these few people could fully feed themselves by personal labor, moreover, without burdening themselves, like the Josephites, with managing peasants and monastic lands, and therefore without distracting their souls from the only important, in Neil’s opinion, monastic work - complete “dying.” world" for the utmost achievable communication with God in prayer, spiritual sobriety and worship. Therefore, the monk never supported any active “acquisition” (that is, simply speaking, acquisition; and it should be emphasized that in ancient times this word did not have the current negative connotation) by the monasteries of any (and above all, land) property. This, however, does not mean at all that Neil opposed all church property as such. He only called for moderation in this area of religious and social life, recognizing the only wealth of a monk as the spiritual gifts of “smart” prayer, and the only acquisition important for a Christian is the acquisition of the gifts of the Holy Spirit.

As Metropolitan Anthony (Bloom), already mentioned above, writes, “in his “Charter” Nil Sorsky indicated that a monk should be so poor that he could not offer even material alms, except for a piece of bread. But he must love a traveler, or a vagabond, or a fugitive robber, or a heretic who has broken away from the Church - he must love them so much that he is ready to share with him all his spiritual experience, the entire content of his soul. Here is a man who sought to know only Christ, Christ crucified; a man who renounced everything material and could not give anything, because he possessed nothing - except God who took possession of him. After all, God is not owned—God takes possession of man, filling him with His breath and His presence.”[21]

And yet, the Monk Neil, despite all his extreme “heritage,” did not at all isolate himself in some kind of purely individualistic solitude, looking indifferently at the troubles and disorders of the world around him, including those that took place within the Church itself. For example, he participated in the meetings of the Council of 1491 against heretics. It was the monks Paisius and Nil who were the first advisers to the Novgorod ruler Gennady in his fight against the Judaizers; It was they who insisted on the need for the speedy publication of the full text of the Bible, which resulted in the preparation of a corpus (albeit still handwritten) of the books of the already mentioned Gennadian Bible. Neil was also involved in church history: in particular, he compiled and edited a new version of the collection of lives of saints - the two-volume Chetya-Minea.

Just as the Monk Nile lived humbly, he died just as humbly, bequeathing to his disciples: “I, unworthy Nile, of my lords and brothers, who are the essence of my character, I pray: at the end of my death, cast my body into the desert, so that the animals and birds may eat it. , because it has sinned to eat much to God and is unworthy to eat burial. If you don’t do this, then dig a ditch in the place where we live and bury me with all dishonor. Fear the word that the great Arseny bequeathed to his disciples, saying: at the trial I will stand with you if you give my body to anyone. For I too had this diligence, great in my strength, so that I would not be worthy of any honor and glory of this age, just as in this life, so also after my death. I pray to everyone to pray for my sinful soul, and I ask forgiveness from everyone, and may there be forgiveness from me. May God forgive us all.”[22].

About the property side, the will says only in a small postscript: “The cross is large, that it contains the stone of the Passion of the Lord, and that I wrote books myself, then - Mr.

for mine and my brethren, who will learn to endure in this place. Small Books, John of Damascus, Potrebnik... - to the Cyril Monastery. And other books and things from the Kirillov Monastery, which were given to me for the love of God; give whatever you have to him, or to the poor, or to the monastery, or to someone who is a lover of Christ, to him, to him.”[23]

And subsequently its deserts remained one of the poorest in the North; the relics of the monk were not opened and were kept buried in a wretched chapel.

***

Venerable Joseph of Volotsky and Nil of Sorsky

To sum up what has been said, it should be noted that if the Monk Joseph at the turn of the 15th–16th centuries headed primarily the Moscow, socially definitely more active branch of Russian monasticism, then the Monk Nil was the main exponent of primarily the internal contemplative ideals of North Russian monasticism.

In essence, both directions in ancient Russian monasticism (relatively speaking, Joseph of Volotsky and Nil of Sorsky) only expressed two sides of the generally unified position of the Russian Church in its relation to the world - simultaneous

recognition of the need for in-depth prayer for him (as the most important task of Orthodox monasticism) and active concern for his real (spiritual and even material) needs. It is not without reason that both saints—Joseph and Nil—have always been equally revered, as they are to this day, by all Orthodox Russia, for each of them played an outstanding role in the development of monastic life in Rus'.

The period of extinction of the activities of the Josephites

In the last quarter of the 16th century, people from the Joseph-Volokolamsk monastery began to rarely be elevated to the rank of bishops of various all-Russian sees. A conflict with the tsar occurred during the years of the oprichnina, when the Monk Herman renounced his metropolitan position and sharply condemned the tsar’s activities during this period. Soon he was killed.

As a result, Tsar John IV Vasilyevich stopped visiting the monastery. The influence of the monastery decreased significantly.

The practice of large-scale ownership of land by the church and the policy of inalienability of church property resonated deeply with the ideology of the formation of autocratic power.

Finally, the Joseph-Volokolamsk Monastery lost its influence as an ecclesiastical and administrative center after the Time of Troubles.

The last and only hierarch in the period after 1613 became Archimandrite Alexander in 1685. He was elevated to the rank of Bishop of Veliky Ustyug.

Assessment of the activities of the Josephites in historiography

At different periods of history, the church and political influence on Rus' was assessed ambiguously by the Josephites.

During the period of power of the USSR, the activities of the Josephites were assessed from a class point of view, considering them essentially controlled by the power of the Grand Duke. It was believed that the position of the Josephites was permeated with feudal interests.

Russian writers abroad considered the victory of the Josephites over non-covetous people as a deep tragedy in the entire spiritual life of Rus'. They believed that the Josephites were far from a state of spiritual freedom and did not think in terms of mystical life.

In foreign literature, the activities of the Josephites were assessed as a catalyst for the emergence of theocratic absolutism.

Results of the dispute

The dispute between supporters of Joseph Volotsky and Nil Sorsky resulted, in essence, into a discussion of the problem of what the church should be in relation to the state. Both the first and the second put forward ideal models.

The “non-covetous” saw her as exclusively prayerful, uninvolved in any earthly goals. They believed that only such a church could have authority among all levels of society and lead Russia forward to high ideals.

The “acquisitors” represented a church organization that stood firmly on its feet, possessed significant property, and therefore did not depend on the authorities. Such a church combines a prayerful attitude with obedience. Ultimately, it may become a spiritually formative force in Russia.