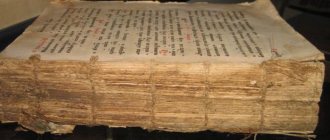

Four Menaions

(cheti - other Russian: for reading, menaia - from the Greek μήν: month) - collections containing, unlike menaia, not liturgical texts, but texts for reading, also arranged by months and days of the year and intended primarily for non-liturgical use.

The Menaion Chetia contain enormous hagiographical and church teaching material, covering a significant part of the reading circle of Ancient Rus'.

The beginning of the formation of the Chetya Menaion in Rus' dates back to pre-Mongol times; the first Chetya Menaion contain mainly translated material, although, apparently, it was also possible to include Russian works (in the Assumption Collection, a manuscript of the 12th century, which can be considered as the Chetya Menaion for May month, the Legend of Boris and Gleb and the Life of Theodosius of Pechersk are placed). A certain processing of the mines was carried out at the end of the century. (this stage has not yet been sufficiently studied).

Great Fourth Menaion

In the middle of the 16th century. The Great Menaion of the Chapel of Metropolitan Macarius appears, a kind of collection of all the literature of Ancient Rus', in which the author, even when he was Archbishop of Novgorod, “collected all the books of the Russian land,” i.e. almost all works of church-narrative and spiritual-educational literature of ancient Rus'; Almost every life or legend is followed by “teachings” or words adapted for reading on the day of remembrance of this or that saint, and entire collections of the words of St. fathers, as well as works of a secular nature, for example, the Old Russian translation of Kozma Indikoplov and others. These additional parts may include entire collections of patristic works, for example, on the day of remembrance of St. Dionysius the Areopagite (October 3) provides the entire corpus of Areopagite writings in the translation of the Serbian monk Isaiah.

The Great Menaions of the Chetya are known hitherto in four lists: a) from the Moscow Assumption Cathedral, now stored in the Moscow Synodal Library (the only complete list); b) the so-called “royal” list, written for Tsar John IV, without March and April. Description of them by Gorsky and Nevostruev with additions by E.V. Barsov, in “Readings of the Moscow History Society”, 1884; c) the list of the Sofia Library and d) the list of the Chudov Monastery - both are incomplete. The publication of these M. was undertaken by the Imperial Archaeographic Commission, but so far only the months of September and October have been published (through the works of P. I. Savvaitov and M. O. Koyalovich).

Chetya Menaion of German Tulupov and priest. Ioanna Milyutin

In the 17th century The chety-menaia were compiled by German Tulupov (in 1627-1632) and priest John Milyutin (in 1646-1654) - manuscripts, the first in the library of the Sergius Lavra, the second in the synodal library in Moscow [1]. Detailed description of M. Milyutin in “Readings in the Society of Lovers of Spiritual Enlightenment”, 1868, book. IV.

Chety Menaion of St. Dimitry of Rostov

At the end of the 17th century. The compilation of four menaia is undertaken by St. Dimitry Rostovsky. His Menaion Chetia were published in quarters from 1689 to 1705. They included only the lives of saints and were compiled on the basis of the Great Menaion Chetia of Metropolitan Macarius, the Acta Sanctorum published by the Bollandists, and a number of other sources. This work has the beginnings of historical criticism.

For three hundred years after the creation of the Chetyih-Menya, St. Demetrius, Met. Rostovsky, a whole series of ancient handwritten lives and chronicles were discovered and introduced into scientific circulation, the existence of which at the turn of the 17th-18th centuries. was not known. Already in the 1st half. XIX century St. Filaret (Drozdov), Metropolitan. Moskovsky, raised the question of the need for significant additions, and in a number of cases, the compilation of new texts for the Chety-Menya lives of those saints, information about which was enriched thanks to hagiographic and historical research. It is important to note that the tradition of adding Chetyih-Menya has always existed in Russian hagiography. Finishing the last, fourth volume in three summer months, St. Demetrius was already preparing corrections and additions to the second edition of the first volume. In a remarkable study dedicated to St. Demetrius, Rev. Alexander Derzhavin wrote that “the saint had the intention to take a rather broad approach to correcting and adding to his books,” but due to illness and death, he only managed to make additions to the first volume of the Chetyi-Menya [2]. After the death of St. Demetrius Chetya-Minea were supplemented by the life of St. himself. Demetrius, and the lives of Saints Equal-to-the-Apostles Constantine and Helena - information from such an important primary source as the book of Eusebius Pamphilus “The Life of Blessed Basileus Constantine”. A number of texts in the Chetya-Minea were subjected to similar modifications.

All chety-menaia of the 18th-19th centuries. are cheti-menaions of St. supplemented with one material or another. Dimitri. The book was reprinted and revised many times, enjoying enormous popularity among the Orthodox population of Russia.

General information

The Old Russian collection is a monthly book (chetya - readings, menaion - a book for worship for the month) and consists of 12 books (a book for each month). The starting point is September 8th. The collection includes patristic teachings, apocrypha and descriptions of the lives of saints for every day.

“The Great Fourth Menaion” accumulates almost all church works of a narrative and spiritual-educational nature. The materials for the collection were translations of Greek church books (the lives of the saints by Symeon Metaphrastus), as well as Limonari, Patericon, and Fatherland. The books of the “Great Menaions” were collected in various cities and monasteries of Ancient Rus' and are presented in four lists: Assumption, Tsar, Sophia and the list of the Chudov Monastery.

Orthodox Electronic Library

“GREAT MINEA-CHETIA” - a collection of patericons, lives of saints, works of church writers, helmsman books, acts, charters, etc. Compiled in the 30-40s. 16th century in Moscow under the leadership of Metropolitan Macarius. 12 volumes, 27 thousand handwritten pages with ornaments. The Great Menaion of Chetiya of Metropolitan Macarius, a kind of collection of all the literature of Ancient Rus', in which the author, even when he was Archbishop of Novgorod, “collected all the books of the Russian land,” i.e. almost all works of church-narrative and spiritual-educational literature of ancient Rus'; Almost every life or legend is followed by “teachings” or words adapted for reading on the day of remembrance of this or that saint, and entire collections of the words of St. fathers, as well as works of a secular nature, for example, the Old Russian translation of Kozma Indikoplov and others. These additional parts may include entire collections of patristic works, for example, on the day of remembrance of St. Dionysius the Areopagite (October 3) provides the entire corpus of Areopagite writings in the translation of the Serbian monk Isaiah.

There are known 3 “fine”, fully completed lists of the Great Mena of the Four, which actually represent 3 independent editions or, more precisely, three 12-volume book collections: Sophia, Uspensky and Tsarsky (the names of the lists are given according to the place of their original storage). The Assumption list of the Great Menaia of the Four is the only one of all three preserved in its entirety on the shelves of the Patriarchal Library (before the revolution). The formation of three white lists of the Great Minyas of the Four lasted approx. 25 years. A general idea of the progress of this process can be formed on the basis of the prefaces (“Chronicles”) by Metropolitan. Macarius, opening the volume of the Great Menaion of the Four. The creation of the Sophia Code of the Great Mena of the Four began in Novgorod in 1529-30 and lasted for 12 years. As evidenced by the insert notes, 12 books of the Sophia list were invested by Macarius in the Novgorod Sophia Cathedral “for the commemoration of the souls” of his parents in 1541. The Metropolitan contributed 12 volumes of the Assumption Great Menaions of the Four as a contribution “for the memory of his soul and for his parents in eternal remembrance” in Assumption Kremlin Cathedral in 1552. Work on the Tsar's List, intended for Tsar Ivan IV, continued as early as 1554. In the 17th century. this list was kept in the royal chambers: on its December book there was a note from clerk Ivan Arbenev about its ownership by Tsar Fyodor Alekseevich and the Order of Books of the Printing House...

The re-release of the Great Mena of the Four was undertaken by the Imperial Archaeographic Commission, but the revolution of 1917 did not allow the re-release to be completed. Only September, October, November, December, January, April were published (through the works of P. I. Savvaitov and M. O. Koyalovich).

Publisher: Printing house of the Imperial Academy of Sciences, Synodal printing house. Language: Russian (pre-reform) / Church Slavonic Format: DjVu Quality: Scanned pages Number of pages: 7341

[124 MB] [10 MB]

List history

The first list was brought from the Moscow Assumption Monastery. Until 1917, it was kept in the synodal library of the capital. This is the only complete list that has survived to this day in handwritten form.

The second list, called the “royal” list, was created specifically for Ivan IV (the Terrible). It contains all months except March and April.

The last two lists have reached us incomplete. Sophia was brought from the library of the cathedral of the same name (Novgorod).

“The Great Fourth Menaion” contains words of praise to the saints, articles of religious and didactic content (Solemnists, Prologues, Breviaries) and works by Basil the Great and Gregory the Theologian. Several collections were included in the Menaion in their entirety. These are “Zlatoust”, “Margarit” and “Golden Chain”. Without preliminary editing, the tome included “The History of the Jewish War” by Josephus, “The Walking of Abbot Daniel” and other monuments of ancient Russian literature. And the value of the collection is all the higher now that the original source materials have not reached the present day. And now it is the most complete set of religious texts, a spiritual encyclopedia of the 16th century.

A century later, the creations of the “Great Four Menaions” formed the basis for other collections: “Menai” by G. Tulupov (1632) and I. Milyutin (1654). They became a favorite reading among literate Christians and were especially popular among Old Believers.

about the author

The “Great Four Menaions” were compiled under the leadership of Macarius, Archbishop of Novgorod, later the All-Russian Metropolitan. At first the collection was called “Makaryev Minaions”. And only later was it presented as the now famous monument of the Orthodox Church.

The creation of the “Great Four Menaions” became one of the most important deeds of Archbishop Macarius on his religious path. Together with his assistants, he collected church and didactic material for about 25 years. And only in 1541 12 books of the month were published and transferred to the library of the St. Sophia Cathedral. The team of compilers included translators, scribes, writers, and publicists. Among them were theologian Zinovy Otensky, writer Vasily Tuchkov-Morozov, clerk Dmitry Gerasimov, priest-hagiographer Vasily-Varlaam and others. The scribes processed the works of all the Novgorod and Pskov libraries that were under the control of Metropolitan Macarius.

In general, the figure of the clergyman was very significant in Ancient Rus'. He had a great influence on the policies of Ivan the Terrible and opposed the Shuisky princes. Under him, new churches were built in Novgorod (St. Nicholas Cathedral, Stoglavy Local). The archbishop paid great attention to the restoration of ancient icons and frescoes. He also contributed to the development of book printing in Rus'. The first printing house was built to publish theological books.

Metropolitan Macarius is the only clergyman who was not persecuted after the fall of the Chosen Rada (the unofficial government of Ivan the Terrible). He died on December 31, 1563 and was canonized as a saint of the Orthodox Church.

Great chetyi-minaia

Known in four lists:

- List of the Moscow Assumption Cathedral. Completely preserved. Before the Revolution of 1917, it was kept in the Moscow Synodal Library.

- Royal list. Written for Tsar Ivan the Terrible. Without March and April. Incomplete.

- List of the Sofia Library. Incomplete.

- List of the Chudov Monastery. Unfinished.

A description of the first two lists was given by A.V. Gorsky and K.I. Nevostruev with additions by E.V. Barsov in 1884.

The Sofia (Novgorod), Uspensky and Tsarsky lists are “fine”, completely completed. In fact, they represent three independent editions, three 12-volume book collections (“cycles”). To date, of the 12 books of the Sofia list, 8 have survived (copies for December, January, March and April have been lost). The Assumption List is the only one of all three that has been preserved in its entirety[5]. From the Tsar's list, 10 volumes have survived (the books for March and April are missing)[6][4].

The collection was compiled under the leadership of Archbishop Macarius of Novgorod, later Metropolitan of Moscow and All Rus' in 1530-1541[2].

The creation of the “Great Four Men” was preceded by large-scale compilation and editorial work: selection of material and distribution of it among volumes and within each volume according to the days of the month; a continuous and significant ideological and stylistic processing of all diverse material, which was carried out in order to maintain presentation in a single solemn and eloquent style of the “second monumentalism”. As a rule, the inclusion of a monument in the “Great Cheti-Minea” led to the creation of its new edition. This is especially evident in the example of lives. When collecting material, often copied from later, damaged copies, corrections were made to “ancient proverbs”: new editions were written based on the oldest ones, new translations were made, or translated biblical, hagiographic and other works were verified and corrected according to their Greek originals. Thus, V.P. Adrianova-Peretz identified corrections to the Greek original in the text of the Life of Alexei the Man of God, included in the text under November 10.

The formation of three white lists lasted about 25 years. Information about the sequence of compilation is provided by the insert notes and prefaces of Archbishop Macarius (“Chronicles”), which precede the volumes. The creation of the Sophia arch of the “Great Chetykh-Menya” began in Novgorod in 1529/1530 and lasted for 12 years. According to the testimony of the insert records, 12 books of the Sofia list were invested by Macarius in the Novgorod St. Sophia Cathedral “for the commemoration of the souls” of his parents in 1541. Macarius deposited 12 books of the Assumption List “in memory of his soul and for his parents in eternal remembrance” in the Assumption Kremlin Cathedral in 1552. Work on the Tsar's List, intended for Ivan IV, continued as early as 1554. The Sophia list was compiled at the Novgorod archbishop's house of Macarius through the labors of “many different clerks” and scribes, who not only copied works, but also remade them and carried out new translations and “corrections” based on the Greek originals, “translating from foreign and ancient proverbs into Russian speech,” - as Macarius wrote about this in the preface.

To form the initial composition of the “Great Mennay”, materials from all Novgorod and Pskov libraries subject to Archbishop Macarius (Sofia, Vyazhitskaya, Otenskaya, etc.) were involved. Work on the Assumption and Tsar's lists was also partially carried out in Novgorod (for example, copying the texts of the Sophia list). Having become Metropolitan of All Rus', Macarius could already attract scribes and scribes from various cities and monasteries from all over Russia to work. The final preparation of these lists probably took place under his supervision in Moscow, in his metropolitan scriptorium. Scribes worked not only in the metropolitan’s book-writing workshops in Novgorod and Moscow, but also, at the behest of the tsar, copied books in other cities of Russia.

According to preliminary observations of V. A. Kuchkin on the November book, the Sophia, Assumption and Tsar lists have complex textual relationships. In the copy taken around 1542 from the Sophia copy of the November Menaion, additional texts (for example, the Explanatory Gospel) were added over the course of 5 years (from 1542 to 1547). The Assumption List of Menaia for November was finally compiled only around 1550. Work on the latest, the Tsar's, list for November was carried out by Novgorod and Moscow masters in two stages, using materials from the Sophia and Assumption lists[7]. E.V. Barsov noted significant differences between the Sofia list and the composition of both Moscow lists. The latter are almost twice as large in volume, thanks to the addition of the lives of Russian saints created in connection with the canonization at the councils of 1547 and 1549 (the Life of Joseph of Volotsky, etc.), the introductory “Chronicles” that set out the content and history of the creation of the “Great Four- Menaion”, in the words of Gregory Tsamblak, “The Revelation of Methodius of Patara[en]”, collections of works by individual authors or biblical books, the Golden Chain, the Bee, etc.[8]

In addition to the three main lists (Sofia, Uspensky and Tsarsky), a later abridged edition of the May book of the “Great Men of Men” of 1569 is known [9], early draft lists of the “Great Men of Men”, for example, the December book [10], as well as editions of the 17th-18th centuries[4].

Editions

The main work of Metropolitan Macarius, “The Great Fourth Menaion,” has undergone several reprints. So, in the 17th century in Kyiv, Bishop Dimitri of Rostov was engaged in this. He significantly shortened the collection and rewrote the hagiographic data in his presentation. The bishop also partially supplemented the “Great Four Menaions” with materials from Latin and Greek books, excluding some Russian apocrypha.

After this, the publication of the collection of monthly words ceased. The name of Metropolitan Macarius and his assistant compilers was forgotten, and Demetrius of Rostov began to be considered the author of the “Great Four Menaions”. Since the 18th century, the collection itself was simply called “The Lives of the Saints of Demetrius of Rostov.”

During the imperial archaeographic commission in 1863-1916, a scientific re-edition of the handwritten volume was made. Collections were published only from September to April. Pavel Savvoitov and Mikhail Koyalovich were in charge of the books.

About the meaning of the Chetyi-Menaion of St. Demetrius for the Russian people

From the earliest times of the Church of Christ, there have been records of the life and work of St. ascetics and confessors. These stories began with St. Evangelist Luke according to the will of St. Paul, who said: “Remember your teachers, who preached the word of God to you, and, considering the end of their lives, imitate their faith” (Heb. 13:7). Following this instruction, Christians have always carefully preserved and preserve information about the lives and deeds of saints. During the period of persecution of the first Christians, records and legends were collected about the holy martyrs, which later became known as acts of martyrdom. With the end of the persecution, a new series of church stories about the saints of God appeared. The collection of these stories received such names as Limonar, Spiritual Meadow, Patericon, Fatherland, etc.

All this served as the basis for the compilation of monthly books, synaxarions and Chetyih-Menya, i.e. arranged by month of readings about the lives and exploits of saints. At the end of the 8th century, 12 books of the Chetyih-Menya already existed in the Church. Not without reason, there is an assumption that in the 10th-11th centuries there already existed a Slavic translation of the Chetyih-Menya for all 12 months. In parallel with this, biographies of the saints of the Russian Church appear and multiply. These lives at first had predominantly the character of a dry and condensed story. But with the proliferation of translations of Greek Lives, especially those revised by Simeon Metaphrast from the 15th century, the lives of Russian saints take on a new look. This new direction is clearly visible in the lives of Stephen of Perm and Sergius of Radonezh compiled by the monk Epiphanius. A new era in the history of hagiography was marked by the activities of Metropolitan. Macarius, whose main business was the Great Menaion-Cheti. It was a complete encyclopedia of Russian spiritual education of that time. A century later, the Chetya-Minea of Russian saints of the monk German Tulupov appeared.

But while similar books existed in Northern Rus', the Southern Russian Church had to be content with Western martyrologies that largely disagreed with the spirit of Orthodoxy. Therefore, the Kiev Metropolitan Peter Mogila decided to make a new translation of the Greek Lives.

But I didn’t have time. Archimandrite was going to implement his idea. Kiev-Pechersk Lavra Innokenty, but also could not due to the military unrest of that time. His successor, Archimandrite Varlaam blessed the monk of the Baturinsky Krupitsky Monastery, Dimitri (Tuptalo), who by that time was already famous as a gifted preacher of Western Rus', to compile new lives.

To his work St. Demetrius began in 1684 and finished in 1705. When writing his Chetya-Menai, St. Demetrius used the Makaryevsky and Greek Chetya-Menaias, the works of the most famous fathers and teachers of the Church, ancient church historians, patericons, and synaxariums. He was engaged in improving his work until the end of his days.

The significance of his work was felt even during his lifetime. After printing the first two parts of the Chetyi-Menya, he received a letter of commendation from Patriarch Adrian. As history has shown, for 200 years, literate Rus' read religiously, and illiterate Russia listened to the Chetyi-Minea of St. Demetrius of Rostov, finding in them an inexhaustible source of moral edification. “The lives of the saints,” according to one of the writers of ancient Russian lives, “instill the fear of God in the soul and introduce good people into acceptance: those of God see their lives, come to a sense of their deeds, and think about the cessation of the evil ones.” Fyodor Mikhailovich Dostoevsky in his article “On the infallible knowledge of the most important essence of the Eastern Question by the uneducated and illiterate Russian people” gives a striking example of the fact that, without reading the Chetya-Minea, without knowing literacy, ordinary Russian people know the lives: “throughout the whole Russian land ... widespread the spirit of Chetya-Minea... because there are extremely many storytellers and storytellers about the lives of saints. They tell stories from Chetya-Minea beautifully, accurately, without inserting a single extra word from themselves, and they are listened to... I myself heard such stories in childhood... I later heard these stories even in the prisons of the robbers, and the robbers listened and sighed... In these stories lies for the Russian people... something repentant and cleansing. Even thin, crappy people often received a strange, uncontrollable desire to go wandering, to purify themselves through labor, feat... Nekrasov, creating his “Vlas”, like a great artist, could not imagine him otherwise than in chains, in penitential wandering... Penitential sorrow, self-accusation, the search for something better, something holy - this is a historical feature of the life of our people.”26 E. Poselyanin in his work “The Russian Church and Russian Ascetics of the 18th Century” states that “after the Gospel, the Lives of the Saints were, perhaps, the book that had a huge influence on believing Russian society. The lives of the Saints represent an inexhaustible treasure of moral creation, a living, convincing, vibrant school of what to look for in life, how to build earthly life.” Indeed, everyone can find something that suits themselves, for in the Cheti-Minea there are biographies of people who held various positions and led different lifestyles, so that everyone can find their own example to follow and follow the established path according to proven rules.

Moreover, the creations of St. Demetrius not only delighted and evoked a desire to imitate the lives of saints of the Church, but also amazed readers with the precision and sophistication of their high style. L.N. Tolstoy, in a letter to Archimandrite Leonid, wrote: “in general, in terms of language, I prefer simplicity and ease of understanding, and I would allow the complexity of the language only when it is picturesque and beautiful, as it is often the case with Demetrius of Rostov.”

A.S. Pushkin o. Based on the Lives of Saints Nicholas Salos of Pskov and John the Great Cap, the poet creates the image of the holy fool in the tragedy “Boris Godunov”. Plots and motifs from the Chetyi-Menya of St. Demetrius also penetrate into the lyrics of A.S. Pushkin. His unfinished poem “The Monk,” written in 1813, is a “sarcastic periphrasis” of the life of John of Novgorod, who managed to defeat the demon with the sign of the cross and, riding it, reached Jerusalem and returned to Novgorod. This is how the poet's work ends:

Fly, old man, sitting on Milk's shoulders, Push him in the back and sides, Fly, hurry to the sacred city of the east, But remember that you did not place your venerable feet on a hinny. Hold on, always stay on the straight road, Because the road to dark hell is wide.

The same episode is uniquely reflected in “The Night Before Christmas” by N.V. Gogol, where the blacksmith Vakula also easily travels on the line to St. Petersburg and back. The writer’s attitude to patristic literature is completely different in the later period of his work, when he will greedily seek readings of the Chetyih-Menya, “The Search for the Bryn Faith,” prayers and other works of Dmitry of Rostov. “My soul now needs more,” he wrote in 1844, “what is written by the Holy Hierarch of our Church than what can be read in French.”

N.I. Kostomarov O. And this is because all the work of Chrysostom of Russia was imbued with God’s grace. The works from his pen were healing and represented the Providence of the Lord. Is this why they, still filled with pure joy and deep wisdom, find a response in the hearts of people?

https://www.russned.ru/stats.php?ID=422

Language and style

Actually, the genre of menaion began to take shape back in the 10th century in Byzantium. There were two types: service (for clergy) and general (for a wider range of readers of spiritual literature).

The “Great Four Menaions” of Metropolitan Macarius combined both types. They were written in Old Russian. Their decoration is in a ceremonial style. The size of each volume of the book compendium corresponds to the name “great”, as it contains 1500-2000 sheets of “Alexandrian” format (approximately equivalent to A4).

The style of presentation of the collections is considered sophisticated and ornate. The pomp and splendor of the words of the “spiritually beneficial to read” texts were not chosen by chance. The style had to correspond to the growing political importance of the Moscow Orthodox kingdom. As for the external monumentality of the tome, it is connected with the idea that Moscow is the heir of Byzantium in world history, that is, the “third Rome.”