Brief biography of the saint

Daniil Savvovich Tuptalo, monk Demetrius, was born in 1651. The birthplace of the saint is Ukraine, Kiev region, the village of Makaryevo. His father, a military centurion, and his mother were pious people who honored the Law of God. Little Daniel grew up in an atmosphere of reverence and respect for God.

The early period of the saint's life

The future saint studied at the Brotherhood School, founded by Metropolitan of Kyiv Peter Mogila. Naturally diligent and purposeful, student Daniil won the favor of his teachers. He was good at languages - Greek, Polish, Hebrew and Latin. The boy also mastered the art of rhetoric and poetics. Brought up in Christian traditions, he studied the teachings of the Holy Fathers.

The diligent young man preferred the silence of the temple, solitude and prayer to student amusements.

In 1665, during the Cossack rebellion against the Polish authorities, the Brotherhood School and the monastery burned down. Daniel returned home and continued to study theology on his own: he read the Holy Scriptures, listened to the instructions of local shepherds and participated in church services. This is how his life choice gradually developed - monasticism.

Monastic period of life

At the age of 18, the young man, with the blessing of his parents, entered the Cyril Monastery in Kyiv. Having passed obedience, he took monastic vows with the name Demetrius in 1668. But monastic life did not last long. The young monk combined zealous service with humility and modesty. His efforts were appreciated and the next year he was elevated to hierodeacon.

Priestly ministry

Deacon Demetrius devoted 6 years to serving the Lord, with devotion similar to that of an angel. For his high personal and spiritual qualities, Metropolitan Lazar Baranovich granted Demetrius the rank of hieromonk and the position of preacher at his own pulpit.

The young shepherd inspired people with fiery sermons and spoke to them in an understandable language. The rumor about the sensitive and educated shepherd spread throughout Ukraine and reached Lithuania. But while teaching his flock about moral improvement, Hieromonk Demetrius was strict with himself. The Lord made sure that his faithful servant did not depart from the duty of a priest and monk, and sent him a dream about this.

For more than a year, Father Dimitri preached at the Slutsk Fraternal Transfiguration Monastery at the invitation of Bishop Theodosius of Belarus. After his death, the preacher, at the insistence of Hetman Samoilovich, returned to his homeland and lived in the Krutitsky Monastery in Nikolaev.

Many monasteries invited Demetrius to be their abbot, but he could not disobey the hetman; out of humility he considered himself unworthy of the responsible position of manager. But, by the will of the Lord, the humble monk had a hand in the arrangement of several monasteries and discovered a new talent in himself.

Hegumen ministry

In 1681, Demetrius became abbot of the Maksakov Monastery. He went to the Chernigov region at the request of the hetman, with the blessing of Archbishop Lazar and the monastery brethren. A year later, the hetman sent him to the Krutitsa monastery in Baturin. Dimitri lived there for a little over a year and a half and received a new offer - to compile the Lives of the saints in the Kiev Pechersk Lavra. The Lord approved the monk's undertaking, sending several Revelations.

After the Lavra of St. Dimitri managed the Baturinsky St. Nicholas Monastery and continued his writing. His works have been published. Writing captured Dimitri. He retired from leading the monastery, but continued to live there in a simple cell. But it was not possible to completely go into creative work.

Father Dimitri was found by Archbishop Feodosius of Chernigov. Having granted the talented preacher and writer the rank of archimandrite, he appointed him to manage the Glukhovsky Peter and Paul Monastery. From there he was transferred to the Trinity-Cyril Monastery in Kyiv. The holy father did not stay long in the monasteries. He served the longest, 2 years, in the Yeletsky Monastery in Chernigov. Then his path lay to the Seversk monastery of the All-Merciful Savior, to Novgorod.

Holy ministry

At the request of Tsar Peter the Great and the blessing of the Metropolitan of Kyiv, in 1700 Father Dimitri went to Moscow to later take up the post of manager of the Siberian department and educate the pagans. The holy father was already in poor health due to wandering from one monastery to another, and the cold of Siberia would have completely torn him down. And he did not see the opportunity to engage in writing in his new position.

Dimitri accepted the upcoming journey and destination humbly, but with sorrow.

He spent a year recovering his health in Moscow, met influential people and government reforms. During this time, the Siberian assignment was given to Bishop Filofei Leshchinsky. And Father Dimitri went to Rostov, to the Yakovlev monastery, where he replaced the deceased Metropolitan of Rostov Joasaph. Here he became closely involved in educational work. Many priests were unscrupulous in serving the Lord. The new metropolitan established discipline and increased literacy among ministers.

Saint Demetrius opened a school for future priests. The training took place at his chambers in the monastery. The Metropolitan himself was involved in the moral education of his students, instructed them, and demanded that they attend services. At the same time, Saint Demetrius fought against schismatics, ignorance and superstitions of the parishioners, held solemn services, continued to write and completed essays on the Lives of the Saints. In 1705, Metropolitan Dimitry of Rostov went to Moscow on call to help fight sects and preach the word of God. After 2 years, he returned to Rostov and continued his pastoral ministry and creative work, despite his serious illness. St. Demetrius reposed on October 28, 1709.

In 1684, Varlaam Yasinsky was appointed archimandrite of the Kiev-Pechersk Lavra. From his predecessors, along with the title of archimandrite, he inherited the idea of the great work of compiling the lives of the saints. This work was all the more necessary because, as a result of Tatar raids, Lithuanian and Polish devastation, the Church lost many precious spiritual books. Looking for a capable person, Varlaam focused his attention on Demetrius, who had already become famous for his zeal for soul-saving works. His choice was approved by the unanimous consent of the other fathers and brethren of the Lavra. Then Varlaam turned to Demetrius with a request to move to the Kyiv Lavra and take upon himself the work of correcting and compiling the lives of the saints. Thus, by the Providence of God, Saint Demetrius was called to the great task of compiling the Chetiih-Menya and brought the greatest benefit to all the people.

Placing hope on the help of God and on the prayers of the Most Pure Mother of God and all the saints, Demetrius began his feat and with great diligence began to undergo the obedience entrusted to him.

The work continued intermittently for 20 years. The Chetii-Minea were written by Demetrius in four books containing lives for three months, and begin according to the church calendar in September.

The first book was printed in Kyiv in 1689.

While Saint Demetrius was working on the second book of the Menaion-Chetei, the new Moscow Patriarch Adrian sent him a letter of commendation. “God himself,” wrote the patriarch, “will reward you, brother, with every blessed blessing, writing you in the book of the eternal life, for your godly labors in writing, correcting and publishing the book of soul-helping lives of the saints for the first three months, Septemvri, Octovr and Noemri: The same one will continue to bless, strengthen and hasten to work for you even for the whole year and other such books of the lives of the saints have been completely corrected and depicted in type.”

The second book was completed in 1690, printed in 1695.

The third book is from 1700. After its printing, Demetrius wrote a small book, “Martyrology in Brief,” containing in it an abbreviated version of the lives of the saints for the year.

In the same 1700, Archimandrite Dimitri was summoned to Moscow. Here on March 23, 1701, his consecration took place with his elevation to the rank of Metropolitan of Siberia and Tobolsk.

The saint met this high appointment with sadness: he was not in good health, and the Siberian climate was destructive for him. But, most importantly, he was burdened by the thought that in order to complete his work “Cheti-Minea” there would be no favorable conditions in Siberia, remote from the centers of education, and there was still a whole quarter of unfinished work. Out of excitement, he went to bed. Tsar Peter allowed him to stay in Moscow and Demetrius continues his painstaking work on the Lives of the Saints, and also often preaches.

In January 1702, Dimitri was named Metropolitan of Rostov and Yaroslavl. The appointment is all the more important because this diocese was at that time greatly shaken by the false teaching of the Bryn schismatics.

Arriving in Rostov, he first of all visited the Spaso-Yakovlevsky monastery. Entering the Cathedral of the Conception of the Mother of God, where the relics of St. James of Rostov rest, the new archpastor performed the usual prayer and at the same time, having learned by a special revelation from above that in Rostov he was destined to end his arduous and useful life, he appointed a grave for himself in the right corner of the cathedral and said to those around him: “Behold my peace: here I will dwell forever and ever.”

Great troubles appeared before the archpastor: vices and ignorance reigned not only among the flock, but also among the clergy. “Our damned time!” - he said in one of his teachings, “I don’t know who is more necessary to take on: the sowers or the land; for the priests or for the hearts of men?.. The sower does not sow, and the earth does not receive. The priests are not careful, but people are mistaken... It’s bad on all sides...”

The saint did not find good moral education among many of the clergy. On the contrary, he had to notice with grief that the fathers of families were not attentive to the fulfillment of the main Christian duties by their household. With the zeal of Elijah, he devoted himself to vigilant concerns about the improvement of the church and the salvation of human souls. As a true shepherd, following the words of the Gospel: “So let your light shine before people, so that they may see your good deeds and glorify your Father in heaven” (Matthew 5:16), the saint himself was a model of piety in everything. At the same time, he tried to eradicate evil morals, envy, lies and other vices in people of all ranks. Saint Demetrius realized that the most effective means for this was good teaching and upbringing. He often said: “What else can enlighten a person if not teaching?” Therefore, he opened a school at his bishop’s house.

However, no matter how burdened the saint was with numerous worries and affairs, even in his new ministry he did not abandon his work on the Lives of the saints. The Chetyi-Minei were his special concern during the first three years of his stay in Rostov.

The last, fourth, book was written almost entirely in Rostov. Compared to the first three, it is noticeably different. Living in Ukraine, the saint almost did not include the lives of Russian saints in his Menaions, only those who were well known in Little Russia. He made only a brief mention of little-known saints, and almost all the ascetics of the north-east of Rus' belonged to them in his monthly book. For example, in the first book of the Menaion (September - November) he placed only eight lives of Great Russian saints, and, moreover, in short editions. Others celebrated during these months are only mentioned in the monthly book. It can be assumed that the saint could not find material for them. But, for example, in the Prologue there are lives and legends about some, but they were not included in the Chetia-Minea. On the other hand, here are the lives of all the Pechersk saints, many of whom were completely unknown in Great Russia.

Having spent a year in Moscow, living in Rostov, the second city in the northeastern region for the abundance of saints after Moscow, the saint could not help but notice that his work suffered from incompleteness. He begins to collect information about the Great Russian saints, and especially those of Rostov. This is evident from his correspondence with friends, to whom he turns with requests for help. The saint searches for and collects the lives of saints and other monuments of ancient writing in his diocese. His manuscripts contain, for example, the life of St. Abraham of Rostov, copied “from the notebooks of the deacon of the Epiphany Monastery.” In Uglich he found a “little book” with the life of St. Tsarevich Demetrius and, supplementing it with information from other sources, placed the life of the prince in the last part of the Chetiih-Minea. In Yaroslavl, in the Church of St. Nicholas Nadein, he found some collection of lives, which in his drafts he calls the “Yaroslavl Chapter”. The saint collected a lot of other material, since he was interested not only in the local saints of God, but also in the shrines of this region in general, intending to write a separate work dedicated to this. The fourth book of the Chetiih-Menai, completed in Rostov, bears clear features of the new views of St. Dimitri. “Among the hagiological material that fills it, we find not only a significant number of lives of Great Russian saints, but also a whole series of stories and legends that are interesting and important only for Moscow and the inhabitants of the northeastern region.”

In the Chronicle of the Bishops of Rostov, the saint himself probably wrote: “In the summer of the incarnation of God the Word 1705, the month of Fevruarius, on the 9th day in memory of St. Martyr Nicephorus, the predicate Victorious, on the occasion of the feast of the Presentation of the Lord, I spoke to St. To Simeon the God-Receiver your prayer: now you release your servant, Master, on the day of the Lord's suffering on Friday, in which Christ said on the cross: it is accomplished, - before the Saturday of remembrance of the dead and before the week of the Last Judgment, with the help of God and the Most Pure Mother of God, and all saints with the prayers, month August peed. Amen".

In 1705, the last book of the Chetiyh-Menai was printed in the Kiev-Pechersk Lavra and thus the Lives of the Saints for a whole year, with twenty years of work by St. Demetrius compiled and published during his lifetime for the benefit of Orthodox Christianity and for the eternal glory of the saint himself.

The Chetiya-Minea of St. Demetrius of Rostov, created by him at the end of the 17th - beginning of the 18th century, is a monument of hagiographic literature that has not lost its significance to this day. Translated from Church Slavonic into Russian, they were reprinted several times during the 18th and 19th centuries and are the favorite reading of the Russian Orthodox people.

Bibliography

The writer Dimitry Rostovsky brought spiritual literature closer to the understanding of the common reader. Before him, all books were written in Old Church Slavonic. In the description of the saint, the martyrs appear before the reader’s inner gaze as if alive. Some of the holy father's works are dedicated to the Passion of Christ and the Mother of God. In his work, the author instructs how to fight unclean thoughts, maintain the purity of the soul and get closer to the Kingdom of God.

Hagiographical and liturgical works

Laudatory works of the saint:

- “The Irrigated Fleece” is about the miracles of the icons of the Mother of God;

- “The Psalter of the Mother of God” is a posthumous collection, psalms from which were published in other collections;

- “Psalms or spiritual cants” - eight praises to the Lord Jesus Christ;

- “Prayers of five” are composed in memory of the sorrows of the Virgin Mary.

From the works of Father Demetrius one can judge the theological views of saints of different eras and the attitude of ordinary people towards religion.

Sermons and Teachings

Metropolitan of Rostov embodied his talent as a preacher and rich managerial experience in the following works:

- “Teachings and Words” - for church holidays, days of remembrance of martyrs;

- “Teachings and sermons” - for the pre-holiday, fast weeks;

- “Teachings to the Priests” - about the duty of a clergyman;

- “Preparation of Priests for Divine Communion” - exposing the blasphemous attitude of priests towards the Holy Gifts and other church attributes;

- “Memory of the spiritual father, how to guide a protege” - rules for a clergyman when elevating a novice to the clergy.

The work “The Word on Drunkenness,” which describes ten corrupting bunches of grapes, is instructive.

Historical and polemical writings

“The Cell Chronicler” is a historical work that describes biblical events before the birth of Christ in chronological order. In it, the saint collected from other works all the information that he considered useful. “Search for the schismatic Bryn faith” is a polemical work proving the falsity of the religion preached by sectarians.

Letters

22 letters were written by the saint during his work in Rostov. Most of the messages are dated 1708-1709 and addressed to the monk Feologus, a friend and Moscow editor.

Treatises

The saint's works are written in a simple style, convey the essence of his thoughts and are distinguished by their brevity. Compared to one-page works, the treatise “Mirror of the Orthodox Confession” can be considered voluminous. It consists of three parts dedicated to faith, hope and love. These components consist of faith in the Lord and virtue, which are necessary for gaining eternal life.

Edifying essays

Brief essays:

- “God-inspired Christian instruction”;

- “Apology for quenching the sadness of a person in trouble, persecution and suffering”;

- “What is it appropriate to thank God for?”;

- "A Brief Christian Moral Teaching."

In a simple form, the author writes about how to be in harmony with the Lord with your soul.

Poetic texts

“Poems on the Passion of Christ” resembles a play and tells about the suffering of Christ. The work includes a poetic appeal from a sinner to Mary Magdalene.

Other works

The saint composed prayers:

- the everyday confession of a person entering the path of salvation;

- prayer verses;

- a brief recollection of the passion of Christ.

The Metropolitan also composed his own “Prayer for his damnation.”

Collections

Two collections are known:

- “The Life and Works of Saint Demetrius”;

- "Symphony of Creations".

The books contain already published edifications, teachings and statements of the Metropolitan.

Attributed writings

The book “The Spiritual Alphabet” was first published in the 18th century. Each letter of the alphabet has a short lesson. The original title of the book is “The Spiritual Ladder”, and the author is Metropolitan Isaiah Kopinsky. There is a version that the printing house made a mistake, since the essay was included with the works of Dmitry of Rostov.

Before “The Alphabet,” “The Ladder” was read by Seraphim of Sarov; the manuscript was found in his personal belongings under that title. Saint Demetrius probably also learned spiritual laws from the manuscript of Isaiah, which the editors turned into the “Alphabet.”

Collected works

“The Lives of the Saints. Twelve Books" tells about the life of Orthodox ascetics, saints, and martyrs. Each book corresponds to a month. Every day there is a biography of a revered saint. The complete “Collected Works” includes 5 volumes. In the multi-volume volume you can find the “Spiritual Alphabet”, the life of the saint, his cell notes and letters.

Lives of the Saints (all months) - Rostov Dimitri

Lives of the Saints. Old Testament forefathers

Preface

In the publication offered to the reader, the lives of the saints are presented in chronological order. The first volume tells about the Old Testament righteous men and prophets, subsequent volumes will reveal the history of the New Testament Church right up to the ascetics of our time.

As a rule, collections of the lives of saints are built according to the calendar principle. In such publications, the biographies of ascetics are given in the sequence in which the memory of saints is celebrated in the Orthodox liturgical circle. This presentation has a deep meaning, for the church’s memory of a particular moment in sacred history is not a story about the long past, but a living experience of participation in the event. From year to year we honor the memory of the saints on the same days, we return to the same stories and lives, for this experience of participation is inexhaustible and eternal.

However, the temporal sequence of sacred history should not be ignored by the Christian. Christianity is a religion that recognizes the value of history, its purposefulness, professing its deep meaning and the action of God's Providence in it. In a temporal perspective, God's plan for humanity is revealed, that is, “childhood” (“pedagogy”), thanks to which the possibility of salvation is open to everyone. It is this attitude to history that determines the logic of the publication offered to the reader.

On the second Sunday before the Feast of the Nativity of Christ, the Sunday of the Holy Forefathers, the Holy Church prayerfully remembers those who “prepared the way for the Lord” (cf. Is. 40:3) in His earthly ministry, who preserved the true faith in the darkness of human ignorance, preserved as a precious gift to Christ, who came to save the lost

(Matthew 18, I). These are people who lived in hope, these are the souls by which the world, doomed to submission to vanity, was held together (see: Rom. 8:20) - the righteous of the Old Testament.

The word “Old Testament” has in our minds a significant echo of the concept of “old [man]” (cf. Rom. 6:6) and is associated with impermanence, closeness to destruction. This is largely due to the fact that the word “dilapidated” itself has become unambiguous in our eyes, having lost the diversity of its originally inherent meanings. Its related Latin word “vetus” speaks of antiquity and old age. These two dimensions define a space of holiness before Christ unknown to us: exemplary, “paradigmatic,” immutability, determined by antiquity and originality, and youth – beautiful, inexperienced and transitory, which became old age in the face of the New Testament. Both dimensions exist simultaneously, and it is no coincidence that we read the hymn of the Apostle Paul, dedicated to the Old Testament ascetics (see: Heb. 11:4-40), on All Saints’ Day, speaking about holiness in general. It is also no coincidence that many of the actions of the ancient righteous people have to be specially explained, and we have no right to repeat them. We cannot imitate the actions of the saints, which are entirely related to the customs of spiritually immature, young humanity - their polygamy and sometimes attitude towards children (see: Gen. 25, 6). We cannot follow their boldness, similar to the power of blooming youth, and together with Moses ask for the appearance of the face of God (see: Exodus 33:18), which St. Athanasius the Great warned about in his preface to the psalms.

In the “antiquity” and “old age” of the Old Testament - its strength and its weakness, from which all the tension of waiting for the Redeemer is formed - the strength of endless hope from the multiplication of insurmountable weakness.

The Old Testament saints provide us with an example of faithfulness to the promise. They can be called genuine Christians in the sense that their entire lives were filled with the expectation of Christ. Among the harsh laws of the Old Testament, which protected from sin human nature that was not yet perfect, not perfected by Christ, we gain insights into the coming spirituality of the New Testament. Among the brief remarks of the Old Testament we find the light of deep, intense spiritual experiences.

We know the righteous Abraham, whom the Lord, in order to show the world the fullness of his faith, commanded to sacrifice his son. Scripture says that Abraham unquestioningly decided to fulfill the commandment, but is silent about the experiences of the righteous man. However, the narrative does not miss one detail, insignificant at first glance: it was three days’ journey to Mount Moriah (see: Gen. 22: 3-4). How should a father feel as he led the most dear person in his life to the slaughter? But this did not happen right away: day succeeded day, and the morning brought the righteous not the joy of a new light, but a painful reminder that a terrible sacrifice lay ahead. And could sleep bring peace to Abraham? Rather, his condition can be described by the words of Job: When I think: my bed will comfort me, my bed will take away my sorrow,

dreams scare me and visions scare me (cf. Job 7:13-14). Three days of travel, when fatigue brought closer not rest, but an inevitable outcome. Three days of painful thought - and at any moment Abraham could refuse. Three days of travel - behind a brief biblical remark lies the power of faith and the severity of the suffering of the righteous.

Aaron, brother of Moses. His name is lost among the many biblical righteous people known to us, obscured by the image of his illustrious brother, with whom not a single Old Testament prophet can be compared (see: Deut. 34:10). We are hardly able to say much about him, and this applies not only to us, but also to the people of Old Testament antiquity: Aaron himself, in the eyes of the people, always retreated before Moses, and the people themselves did not treat him with the love and respect with which they treated their teacher . To remain in the shadow of a great brother, to humbly carry out one’s service, although great, is not so noticeable to others, to serve a righteous man without envying his glory - isn’t this a Christian feat already revealed in the Old Testament?

From childhood, this righteous man learned humility. His younger brother, saved from death, was taken to the palace of the pharaoh and received a royal education, surrounded by all the honors of the Egyptian court. When Moses is called by God to serve, Aaron must retell his words to the people; Scripture itself says that Moses was like a god for Aaron and Aaron was a prophet for Moses (see: Ex. 7: 1). But we can imagine what enormous advantages an older brother must have had in biblical times. And here is a complete renunciation of all advantages, complete submission to the younger brother for the sake of the will of God.

His submission to the will of the Lord was so great that even sorrow for his beloved sons receded before her. When the fire of God burned Aaron's two sons for carelessness in worship, Aaron accepts the instruction and humbly agrees with everything; he was even forbidden to mourn his sons (Lev. 10:1-7). Scripture conveys to us only one small detail, from which the heart is filled with tenderness and sorrow: Aaron was silent

(Lev. 10:3).

We have heard about Job, endowed with all the blessings of the earth. Can we appreciate the fullness of his suffering? Fortunately, we do not know from experience what leprosy is, but in the eyes of superstitious pagans it meant much more than just a disease: leprosy was considered a sign that God had abandoned man. And we see Job alone, abandoned by his people (after all, Tradition says that Job was a king): we are afraid of losing one friend - can we imagine what it’s like to lose a people?

But the worst thing is that Job did not understand why he was suffering. A person who suffers for Christ or even for his homeland gains strength in his suffering; he knows its meaning, reaching eternity. Job suffered more than any martyr, but he was not given the opportunity to understand the meaning of his own suffering. This is his greatest sorrow, this is his unbearable cry, which Scripture does not hide from us, does not soften, does not smooth out, does not bury it under the reasoning of Eliphaz, Bildad and Zophar, which, at first glance, are completely pious. The answer is given only at the end, and this is the answer of Job’s humility, which bows before the incomprehensibility of God’s destinies. And only Job could appreciate the sweetness of this humility. This infinite sweetness is contained in one phrase, which for us has become a prerequisite for true theology: I have heard of You by the hearing of the ear; now my eyes see You; so I renounce and repent in dust and ashes

(Job 42:5-6).

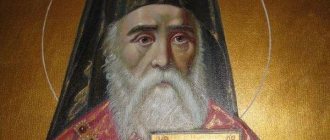

Iconography

The Metropolitan of Rostov is depicted to the waist and in full height in the solemn vestments of a bishop. In the left hand of the saint is the bishop's staff. On the head is a miter or hood. He is often depicted with books. Icon painters took lifetime portraits as a basis. Therefore, the saint appears either against the background of the temple, or next to the lectern. The Vatopedi Icon of the Mother of God hung in the metropolitan’s cell. The image was located at the saint’s tomb and became part of his iconography.

Quotes from his writings are added to the icons of St. Demetrius, often from the Cell Chronicler. There are also images with the text of the troparion to the saint.

Reverence

Christians have glorified the saint since the second half of the 18th century, after the spread of rumors about his miraculous relics. The society of that time did not believe in the emergence of new saints.

A stream of pilgrims poured to the relics of the Metropolitan of Rostov. By order of Empress Elizabeth Petrovna, they were placed in a silver shrine. And Catherine the Second donated to the Yakovlevsky Monastery an icon by the Italian artist Rotary, which was later lost. Until the beginning of the 20th century, the laity received spiritual education from the Lives of the Saints and printed sermons of the saint. The books of St. Demetrius were respected by classical writers - Dostoevsky, Gogol, Turgenev.

A friend of A. S. Pushkin, the poet V. Kuchelbecker, was even healed of an eye disease thanks to prayers to the saint and dedicated a poem and a poetic prayer to him. There is also a dedication to Demetrius of Rostov in the works of I. Bunin, written after visiting the Yakovlevsky Monastery.

Day of Remembrance

The saint is commemorated on May 3, at the Cathedral of Rostov Saints, and on October 28, the day of his death.

Finding the relics

The date of the discovery of the incorruptible relics of the saint is September 21/October 4. On this day in 1752, during the repair of a log house at the grave of the Metropolitan of Rostov, it was discovered that his body had not decomposed. The manuscripts lying nearby had become dilapidated, but the relics and clothing remained unchanged.