Hearing the phrase “Orthodox cathedral,” people immediately imagine a building where priests conduct services and there are icons from which the stern faces of saints look down. People also associate it with various church symbols: incense, censer, candlesticks, etc. It is probably impossible to get used to the splendor of the temple and treat it casually. For those who come to church for the first time, it is sometimes difficult to adapt to the words that are heard during services or rituals. Therefore, it is worth preparing in advance.

The meaning of the word omophorion

The great feast of the Intercession of the Blessed Virgin Mary is approaching. During the service glorifying the Mother of God, the clergyman repeats the phrase more than once: “Cover us with your omophorion.” For those unfamiliar with the Church Slavonic language, it is not clear what we are talking about.

Literally translated from Greek, “omophorion” means “carried on the shoulders.” In other words, it is a robe that is thrown over the shoulders. Remember the icons depicting the face of the Blessed Virgin. She always has her head covered; as a rule, it is a wide shawl that falls freely over her shoulders.

It is with the omophorion that the Mother of God covers people to protect them from troubles and troubles. If you look at the paintings of great artists who depicted women from the Far East or characters from the Bible, you can understand that this item of clothing was an integral part of girls’ attire.

More than two thousand years have passed, but Jewish women still wear a scarf over their heads. And Christian women will never cross the threshold of a temple with their hair uncovered. In Orthodoxy, only bishops can wear an omophorion.

| For Russians, such a word is unusual and hurts the ear, so we call the wide scarf “veil.” The name of the veil is inextricably linked with the holiday dedicated to the Mother of God. |

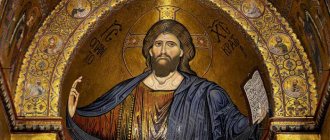

Image of the Mother of God “Hodegetria” (“Guide”)

On such relics, the Heavenly Queen holds Jesus in her arms, His face is turned to the viewer, one hand of the Son of God is folded in a blessing gesture, and in the second a scroll is clenched - a sign of His teaching. The hand of the Virgin Mary points to the Savior, calling on all believers to worship the Lord, who opened the way for people to deliverance from death. Both figures are captured frontally (turned towards the person looking at the image). Most often, such shrines are waist-length, but there are also shoulder-length and full-length versions.

The symbolism of these relics is radically different from the meaning of the “Tenderness” icon of the Mother of God. Here the center of the composition is Jesus Christ, appearing in the hypostasis of the Almighty (Pantocrator), Heavenly King and Judge. Such shrines remind of the righteous Christian path, help with personal or professional difficulties, and soothe melancholy and sadness. They bless newborns and newlyweds - it is believed that then grace will accompany them throughout their lives.

The Georgian, Iversky, Jerusalem, Kazan, Smolensk, Tikhvin and Czestochowa images of the Heavenly Queen, as well as the icons “Deliverer”, “Three-Handed”, “Quick to Hear” were painted in this manner.

What is the purpose of the omophorion?

What is this mysterious robe of the Omophorion of the Blessed Virgin Mary? Nowadays it is represented by two models: great and small. The first is a wide ribbon on which strips of a fabric other than the product itself are sewn. They wear it as follows: they put it around the bishop’s neck and one end is lowered from the left shoulder to the chest, and the other lies on the back.

The ends of the omophorion fall almost to the hem of the sakkos. This is a spacious robe of a bishop with wide sleeves. Only expensive fabrics are used to sew it. The ends of the ribbon are decorated with embroidery in the form of crosses. Symbolically, the omophorion means gifts of grace to the clergy. Bishops do not have the right to conduct the Divine Liturgy without this attire.

The ribbon is also a kind of reminder to the bishop that he must be attentive to his flock and take care of them. In other words, the same way Christ behaved with the lost sheep. If you don’t remember, he picked her up on his shoulders and carried her home.

The great (large) omophorion of the bishop is worn from the beginning of the Liturgy until the reading of the Apostles (epistles located in the New Testament). During the ascension of the Gospel, the bishop completely removes his robe. After finishing his reading, the clergyman is dressed in a small omophorion. It is practically no different from its older “brother”, only several times shorter.

The product is draped around the bishop's neck, with both ends of the ribbon falling onto his chest. The small omophorion is no less significant in Orthodox services and priestly vestments. But it has a different mysterious meaning. Such a ribbon symbolizes that the bishop is the bearer of grace-filled gifts. For this reason, a metropolitan, bishop or patriarch cannot conduct the Liturgy without an omophorion.

Iconography of the Blessed Virgin Mary

Images of the Mother of God occupy an exceptional place in Christian iconography, testifying to Her significance in the life of the Church. The veneration of the Mother of God is based on the dogma of the Incarnation: “The indescribable word of the Father, from you the Mother of God is described incarnate...” (kontakion of the 1st week of Lent), therefore, for the first time, Her image appears in such scenes as “The Nativity of Christ” and “The Adoration of the Magi.” From here other iconographic themes subsequently develop, reflecting the dogmatic, liturgical and historical aspects of the veneration of the Mother of God. The dogmatic significance of the image of the Mother of God is evidenced by Her image in the altar apses, since She symbolizes the Church. The history of the Church from the prophet Moses to the Nativity of Christ appears as the action of Providence about the birth of She through whom the salvation of the world will be realized, therefore the image of the Mother of God occupies a central place in the prophetic row of the iconostasis. The development of the historical theme is the creation of hagiographic cycles of the Virgin Mary. The most important aspect of the veneration of the Mother of God, as evidenced by many miraculous icons, is the belief in Her intercession for the human race “all the days.” The main directions of veneration of the Mother of God appeared in various forms. Temples are dedicated to her. Her images occupy the most important place in the system of temple decoration, largely determining its symbolism. The iconography of the Mother of God is distinguished by the variety of types; icons and objects of plastic art, including decorations of the Mother of God images, are widespread. Icons of the Mother of God and their liturgical veneration contributed to the formation of developed liturgical rites, gave impetus to hymnographic creativity, and created a whole layer of literature - legends about icons, which in turn was the source of further development of iconography.

The veneration of the Mother of God developed primarily in Palestine. The most important events in the life of the Mother of God were associated with the cities of Nazareth, Bethlehem and Jerusalem; Her relics and Her first icons were kept there. In these memorable places, churches were built in honor of the Annunciation and the Nativity of Christ. A significant center of veneration of the Mother of God was Constantinople, where the most ancient icons and shrines of the Mother of God were collected, churches were built in Her honor, and the city was conceived under the protection of the Blessed Virgin. After the Third Ecumenical Council, the veneration of the Mother of God became widespread throughout the Christian world. From the 6th century Icons of the Mother of God play an important role in the veneration of the Mother of God. The main types of images of the Virgin Mary developed already in the pre-iconoclastic period, the earliest are found in the paintings of the Roman catacombs: the image of a seated woman with a naked baby in her arms in the Velato cubicle of Priscilla’s catacombs (2nd half of the 2nd century – 1st half of the 3rd century) interpreted as an image of the Virgin Mary; Also in the catacombs of Priscilla, a fresco representing the Virgin Mary on the throne in the scene of the “Adoration of the Magi” (IV century) has been preserved. The determining role in the formation of the iconographic type “Virgin on the Throne” was played by the paintings of the Church of Santa Maria Maggiore in Rome (432–440), where for the first time in Christian art this image was presented in the apse concha (not preserved). The image of the Virgin Mary on the throne, placed from the 5th century. in the conchs of the altar apses, replaced the images of Jesus Christ located there in an earlier era (Cathedral of St. Euphrasian in Porec (Croatia), 543–553; Church of Panagia Kanakarias in Lythrangomi (Cyprus), 2nd quarter of the 6th century). Images of the Virgin and Child enthroned are also found on the walls of the central naves of basilicas (Sant'Apollinare Nuovo in Ravenna, 6th century; Martyr Demetrius in Thessalonica, 6th century; Felix and Adauctus in the catacombs of Priscilla in Rome, 6th century), on icons (for example, from the monastery of the Great Church of Catherine on Sinai, 6th century), as well as in works of small plastic art (for example, ampoules of Monza (treasury of the Cathedral of St. John the Baptist in Monza in Italy), diptychs (avory , VI century, State Museums of Berlin)).

Another common type of depiction of the Blessed Virgin is the Oranta, where the Virgin Mary is represented without the Child with her hands raised in prayer (for example, on ampoules from the treasury of the Cathedral of Bobbio) (Italy), on the relief of the door of the Church of Santa Sabina in Rome, c. 430, on a miniature from the Gospel of Rabbi (Laurent. Plut. I.56. Fol. 277, 586), on the frescoes of the apse of the monastery of St. Apollonius in Bauita (Egypt, 6th century) and the San Venanzio Chapel in Rome (c. 642), as well as on the bottoms of glass vessels (see: Kondakov, pp. 76–81)).

One of the most common is the image of the Mother of God Hodegetria, named after the Constantinople temple in which this revered icon was located. According to legend, it was written by the Evangelist Luke and sent from Jerusalem to the Emperor. Evdokia. The earliest image of Hodegetria has been preserved in miniature from the Gospel of Ravbula (Fol. 289 - full-length). In icons of this type, the Mother of God holds the Child in her left hand, with her right hand extended to Him in prayer.

During the period of iconoclastic persecution, the miraculous image of the Mother of God, according to legend, which appeared during the life of the Blessed Virgin on the pillar of the temple built by the apostles in Lydda, became widely known. A copy of the miraculous image, brought from Palestine by Patriarch Herman, is revered as the miraculous Lydda (Roman) icon of the Mother of God (an image of Hodegetria with the Child on her right hand).

The image of the Mother of God of Nikopeia, holding with both hands, like a shield, a medallion with the image of the Infant Christ, was especially revered in Constantinople. This image is first found on the seals of the Emperor. Mauritius (582–602), whom, according to legend, the icon accompanied in wars. The establishment of the feast of the Dormition of the Virgin Mary is also associated with the Emperor Mauritius. Images of the Mother of God with an oval icon of Christ in her hands are known in the paintings of the monastery of St. Apollonia in Bauita and the church of Santa Maria Antiqua in Rome (8th century). In the East during this period, the image of the Virgin Mammal was widespread (frescoes of the monasteries of St. Jeremiah in Saqqara (5th century) and St. Apollonius in Bauita), emphasizing the theme of motherhood and the incarnation of God.

The types of images of the Virgin Mary that appeared in early Christian art received further distribution and development in the art of Byzantium, the Balkans, and Ancient Rus'. Some iconographic versions have been preserved almost unchanged, for example, the image of the Mother of God on the throne with the Infant Christ sitting frontally on the Mother’s lap. She holds Him with her right hand at the shoulder and with her left at the leg. Such an image is most often presented in the conch of the altar apse (in the churches of St. Sophia of Constantinople, 876; in the katholikon of the Hosios Loukas monastery in Phokis (Greece), 30s of the 11th century; in the church of Martyr George in Staro Nagorichino (Macedonia ), 1317–1318; in the Church of the Nativity of the Virgin Mary in the Ferapontov Monastery, 1502, etc.). A repetition of the ancient pattern is the image in the altar of the church of St. Sophia in Ohrid (30s of the 11th century) of the Mother of God Nikopeia, holding the image of the Child in a medallion, however, in the post-iconoclast period, the type of Mother of God Nikopeia (full length) with the Child depicted not in the medallion became widespread (for example, in Church of the Assumption of the Virgin Mary in Nicaea, 787 (not preserved); in Hagia Sophia of Constantinople, 1118; in the cathedral of the Gelati Monastery, ca. 1130). The type of the Virgin Mary with the image of the Child in a medallion is known in several variants: with the image in front of the chest, in the height of Oranta, Blachernitissa (Great Panagia) (marble relief of the 12th century from the church of Santa Maria Mater Domini in Venice; icon of the Mother of God with the prophet Moses and the Patriarch Euthymius (XIII century, monastery of the Martyr Catherine on Sinai), the icon “Yaroslavl Oranta” (XII century, Tretyakov Gallery); painting of the Church of the Savior on Nereditsa, 1199 (image not preserved)), and a half-length image (known in Russian tradition like the “Sign”, for example, the icon of the Mother of God from the St. Sophia Cathedral in Novgorod, around 1160; mosaic of the narthex of the Chora Monastery (Kakhrie-Jami) in Constantinople, 1316–1321). Numerous iconographic variants were given by the Hodegetria type, which includes such miraculous icons as Smolensk, Tikhvin, Kazan and others. In the post-iconoclastic period, images of the Mother of God Eleusa (Merciful), Glycophilus (Sweet kiss; in the Russian tradition Tenderness), also known under the name Blachernitissa (12th century icon, monastery of Martyr Catherine on Sinai), where the Mother of God and the Child are depicted in mutual caress, spread ( fresco of the church of Tokaly-kilise, Cappadocia (10th century), Vladimir, Tolga, Don icons of the Mother of God, etc.). This type of image emphasizes the theme of motherhood and the future suffering of the Infant God, most clearly expressed in Pelagonitis, a miraculous image from the Pelagonian diocese in Macedonia. In the Russian tradition, this icon was called “Leaping” (fresco of the monastery of the Church of Martyr George in Staro-Nagorichino (Macedonia), 1317–1318; icon from the Monastery of the Transfiguration in Zrze (Macedonia), XIV century), since the Baby on it is depicted breaking out from the hands of the Mother of God. The theme of Christ's suffering is also expressed in the iconography of the Passionate Virgin Mary, usually presented in the type of Hodegetria (fresco of the Church of Panagia Arakos in Lagoudera) or Tenderness (Russian icon of the 13th century, TGOM; icon of the 15th century (Byzantine Museum)), with angels on the sides, which holding the instruments of passions.

In addition to the frontal position, images of the Mother of God in prayer can represent a figure in a 3/4 turn. Such images have been known since pre-iconoclast times. The hands of the Mother of God are stretched out prayerfully to Christ, for example, in the images of the Mother of God of Agiosoritissa (Chalcopratia) (mosaic in the Church of the Great Martyr Demetrius in Thessalonica, 6th century (not preserved), miniature from the Christian topography of Cosmas Indicopleus (Vat. gr. 699 . Fol. 76, 9th century); icon of the 12th century (monastery of the Martyr Catherine on Sinai); icon from the Assumption Cathedral of the Moscow Kremlin, 14th century) and in the compositions of the Deesis, as well as the Mother of God Paraklisis (Intercessor), holding holding a scroll with the text of a prayer addressed to Christ (mosaic of the church of Martyr Demetrius, 7th century; Bogolyubskaya Icon of the Mother of God (Assumption Cathedral of the Princess Monastery in Vladimir, mid-12th century); icon from the cathedral in Spoleto (Italy); 12th century ., fresco of the cathedral of the Mirozhsky monastery in Pskov, XII century; mosaic of the Church of Martorana in Palermo (Sicily), XII century).

Often the names of certain iconographic types are identified with epithets of the Mother of God or are toponyms indicating the place where the revered image is located (in the Russian tradition they received their name, which does not always literally convey the original), and can be found on icons of various versions. The mentioned icon of the Eleusa type from the VMC monastery. Catherine in Sinai (XII century) is accompanied by the inscription “Blachernitissa”, which is associated with the existence of a revered image of this type in the Blachernae Temple of Constantinople. On a mosaic icon of the same type from the Byzantine Museum (12th century) it is written guarantor, intercessor or patroness; images of Hodegetria may have the inscriptions “Eleusa” (Khilandar Monastery, Athos, XIV century), “Beautiful” and “Soul Savior” (both - XIV century, museum in Ohrid (Macedonia)); “The Most Graceful” and “The Tsarina of All” (both – 16th century, STsAM), etc.; on the icon of the Mother of God Oranta with the image of the Child in front of the chest there is the inscription “Guide” (XV century?, TsAK MDA).

Symbolic epithets of the Mother of God can be the name of a certain iconographic type. Such icons include, for example, the image of the Mother of God “Life-Giving Source,” which was located in the temple of the same name near Constantinople. The Mother of God is depicted waist-deep in a phial (a bowl with a fountain), without the Child, with her hands raised in prayer (mosaic of the Chora Monastery in Constantinople; Church of the Holy Archangels in Lesnov (Macedonia), 1347–1348) or with the Child, whom She holds with both hands (fresco of the monastery of St. Paul on Athos, 1423; Russian icon 1675, Central Museum of Art and Culture). Icons based on literary epithets of the Mother of God, such as “The Unfading Flower”, “Blessed Womb”, “Seeking the Lost”, “Joy of All Who Sorrow”, “Support of Sinners”, “Burning Bush”, “Mountain”, were especially widespread in the Russian environment. not hand-cut”, “Impenetrable Door”, etc.

The richest source of the Mother of God iconography are liturgical texts, primarily hymnographic ones. The heyday of this type of iconography occurs at the end. XIII-XVI centuries Lengthy poetic cycles dedicated to the Mother of God are illustrated, both the Akathist of the Mother of God, and individual hymns, the central image of which is the Mother of God, for example, the stichera “What shall we bring to Thee, O Christ” (“Cathedral of Our Lady” - fresco of the Church of the Savior of the Žiča monastery (Serbia), 13th century .; fresco of the Church of the Virgin Mary Perivelept in Ohrid, 1295; icon of the late XIV - early XV centuries, Tretyakov Gallery); honoree of the liturgy of St. Basil the Great “Rejoices in You” (late 15th century icon, Tretyakov Gallery); fresco of the Nativity Cathedral of Ferapontov Monastery, 1502); the verse “It is worthy to eat” (icon of the mid-16th century, Assumption Cathedral of the Moscow Kremlin), the Mother of God of the 1st hour “What shall we call Thee” (icon of the 17th century, Central Museum of Art and Culture). The liturgical images also include “Praise of the Mother of God,” based on the chant “Above the prophets foretell Thee” (14th-century icon and 15th-century fresco from the Assumption Cathedral of the Moscow Kremlin; 16th-century icon, Russian Museum). The theme of the icons is the events celebrated by the Church, associated with the veneration of the Mother of God and shrines - “Protection of the Most Holy. Mother of God" (stamp of the west gate of the Cathedral of the Nativity of the Virgin in Suzdal, XII century; icon of the XIV century, NGOMZ; icon of the XIV century, Tretyakov Gallery), "Position of the robe of the Most Holy. Mother of God" (XV century, TsMiAR).

In addition to liturgical texts, the basis of the Mother of God icons can be historical narratives. For example, the miraculous Pskov-Pokrovskaya Icon of the Mother of God depicts the events of the siege of Pskov by the troops of Stefan Batory in 1581 (comes from the Church of the Intercession of Prolom, stolen during the Great Patriotic War, from September 7, 2001 in the Trinity Cathedral of Pskov.

In close connection with the formation of the iconography of the feasts of the Mother of God is the development of the life cycle of the Mother of God; its images are based on the apocryphal Proto-Gospel of James, the Word of the Apostle John the Theologian on the Dormition, the Word of St. John of Thessalonica and a number of other texts telling about the events of the life of the Mother of God from Her conception by the barren Anna to the Assumption. Individual images of apocryphal subjects were known already in the pre-iconoclastic period, for example, a plate with scenes of the Annunciation and the Trial of Conviction by Water (VI century, GMVI). In the painting of the Kyzylchukur church (Cappadocia; 850–860), the earliest life cycle of the Virgin Mary is preserved, including 10 scenes from the Annunciation to Anna to the Entry of the Virgin Mary into the temple. The same subjects are presented in the miniatures of the Minology of Basil II (Vat. gr. 1613, 976–1025) and the mosaics of the Church of the Assumption of the Virgin in Daphne (c. 1100). In the painting of the Cathedral of St. Sophia of Kyiv (30s of the 11th century), the proto-Gospel cycle, ending with the scene of “The Meeting of Mary and Elizabeth,” is presented in the southern apse, to the right of the central altar; in the cathedral of the Mirozhsky Monastery in Pskov (40s of the 12th century) a cycle located in the southwest. compartment, included more than 20 compositions (16 saved); in the Novgorod churches of the Nativity of the Virgin Mary at the Antoniev Monastery (1125), the Annunciation in Arkazhi (80s of the 12th century), the Savior on Nereditsa (1199, frescoes not preserved), St. George in St. Ladoga (2nd half of the 12th century) the hagiographic cycle of the Mother of God is in the altar. The proto-evangelical cycle may include compositions: the bringing of gifts by the righteous Joachim and Anna, the rejection of gifts, the crying of Joachim and Anna, the prayer of Anna, the prayer of Joachim, the test of the scriptures, the gospel to Anna, the gospel to Joachim, the meeting of Joachim and Anna at the Golden Gate, the Nativity of the Most Holy One. Mother of God, caressing Mary, feeding Mary, the first seven steps of the Most Holy. Theotokos, presentation to the elders, introduction to the temple, prayer for the rods, presentation of Mary to Joseph, Joseph leading Mary to his house, Annunciation at the well, meeting of Mary and Elizabeth, Joseph's reproaches, Joseph's dream, trial of reproof by water.

In the XIII-XIV centuries. The life cycle of the Mother of God is expanded by the narrative of the Dormition of the Mother of God, which includes scenes: farewell to the women of Jerusalem, farewell to the apostles, the ascension of the Mother of God and the presentation of the belt, the transfer of the body of the Mother of God to the burial place, the cutting off of the hands of the wicked Authonia by an angel, the apostles at the empty tomb of the Mother of God. One example of such a lengthy cycle is the painting of the Church of the Virgin Mary Periveleptus (St. Clement) in Ohrid (1395). Scenes from the Proto-Gospel and Assumption cycles occupy the middle register of the southern wall and the western wall (for example, in the Church of Joachim and Anna (Kraleva) of the Studenica Monastery (Serbia), 1314). In the church of the Chora Monastery, 20 compositions of the proto-Gospel cycle are presented on the vaults and walls of the exonarthex.

In the XV-XVI centuries. In Russian art, icons of the Mother of God with scenes of life in stamps are becoming widespread. Similar images were known in Byzantine art (diptych of the 12th century, State Museum of Berlin). On Russian icons, among the subjects of the Assumption cycle, the following stand out: The Prayer of the Mother of God on the Mount of Olives, the Annunciation of Death, The Position of the Robe and Belt of the Mother of God (Tikhvin Icon of the Mother of God with the marks of the Life, 15th century, NGOMZ; Smolensk Icon of the Mother of God, 16th century, Tretyakov Gallery). Hagiographic icons of the Mother of God were the basis for the development of a fundamentally new type of icon with a legend of miracles. This iconographic type, known in Byzantine art, was developed in Rus' in the 2nd half. XVI-XVII centuries, which is associated with the liturgical veneration of miraculous icons and the compilation of special services for them. The development of the text of the legend was directly reflected in the monuments of the iconography of the Mother of God, based on various editions of the text (“Vladimir icon with the marks of the legend of Temir-Aksak”, XVI century, PGKhG; “Vladimir icon with 64 marks of the Legend of her miracles”, XVII century. , TsMiAR; Tikhvin icon, XVI century, Annunciation Cathedral of the Moscow Kremlin; Tikhvin icon from Balakhna with scenes of the siege of the monastery by the Swedes, XVII century, TsMiAR; Tikhvin icon with life and miracles in 99 stamps, XVII century, Assumption Cathedral of the Moscow Kremlin; Kazan Icon, 17th century, SIHM; Tolga Icon, 17th century, YAHM cf.: Theodorovskaya Icon, 2001, Pakhomiev Nerekhta Convent of the Kostroma Diocese).

Often the subject of a separate icon was an episode from the legend of the miracles of another image of the Mother of God. For example, the Besednaya Icon depicts the miracle of the appearance of the Mother of God to sexton George, the story of which is contained in the legend of the Tikhvin Icon; The plot of the icon “The Presentation of the Vladimir Icon of the Mother of God” (XVI century, Central Museum of Art and Culture) is an episode from “The Tale of the Miracles of the Vladimir Icon of the Mother of God.”

The iconography of the Mother of God images was significantly enriched in later times. In the XIX-XX centuries. the icons of the Mother of God “Tenderness” of Seraphim-Diveyevo (the cell of St. Seraphim of Sarov) became famous, on which the Mother of God without the Child is represented with her arms crossed on her chest, with a halo surrounded by fiery tongues, “The Spreader of the Loaves” (the name was given by St. Ambrose of Optina), where the appearance in the heavens of the Mother of God blessing the fields, found in the village of Kolomenskoye “Derzhavnaya”, is captured. The attitude of the Russian Church to the images of the Mother of God is deeply and accurately expressed in the words of the hymn to the Mother of God: “And to this day with mercy.”

Literature:

Snessorev. Earthly life of the Blessed Virgin Mary; Bukharev I. Icons; Likhachev N.P. Materials for Russian history. iconography. St. Petersburg, 1906; aka. Historical significance of Italo-Greek painting: The image of the Mother of God in the works of Italo-Greek icon painters and their influence on the compositions of some famous Russian icons. St. Petersburg, 1911; Villager E. Mother of God; Kondakov. Iconography of the Mother of God; Maria. Etudes sur la Saint Vierge. P., 1949–1961. 1–5; Lexikon der Marienkunde. Regensburg, 1957; Lafontaine-Dosogne J. Iconographie de l'enfance de la Vierge dans l'Empire byzantin et en Occident. Brux., 1964–1965. Vol. 1–2; Grabar A. Christian Iconography: A Study of Its Origins. Princeton, 1968; idem. Les images de la Vierge de Tendressë type iconographique et theme (a propos de deux icones de Decani) // Zograf. Beograd, 1975. P. 25–30; idem. Remarques sur 1'iconographie byzantine de la Vierge // Cah. Arch. P., 1977. Vol. 26. P. 169–178; Lazarev V.N. Sketches on the iconography of the Mother of God // aka. Byzantine painting. M., 1971. S. 275–329; aka. Sketches on the iconography of the Mother of God // Byzantine and Old Russian. art: Articles and materials. M., 1978. S. 00; Grabar A. L'Hodigitria et l'Eleousa // ZLU. 1974. T. 10. P. 3–4; Sevcenko NP Types of the Virgin Mary // The Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium. NY; Oxf., 1991. Vol. 3. P. 2175–2176; Mouriki D. Variants of the Hodegetria on two thirteenth-century Sinai icons // Can. Arhc. 1991. Vol. 39. P. 153–182; Smirnova E. S. Icon of Our Lady of Maximovskaya: Revival of Russian. artistic tradition at the end of the 13th century. // DRI. M., 1993. [Issue:] Problems and attributions. pp. 72–93; she is the same. Novgorod icon “Our Lady of the Sign”: some issues of the Mother of God iconography of the 12th century. // DRI. St. Petersburg, 1995. [Issue:] Balkans, Rus'. pp. 288–309; Miraculous icon in Byzantium and others. Rus' / Ed.-comp. A. M. Lidov. M., 1996; LCI. Bde. 3. S. 154–233 (Bibliography); Etingof O. E. Image of the Mother of God: Very good. Byzantine iconography of the 11th-13th centuries. M., 2000.

Great Worship

Liturgy is considered one of the most terrible and mysterious services, which carries particles of eternity. All believers know that during the Eucharist, bread miraculously turns into the body of Jesus, and wine into his pure blood. At these moments, parishioners receive communion with trepidation and reverence. Moments like these remain in memory for a lifetime.

| During the divine service, the bishop represents the Savior of mankind. With his attire, he demonstrates to parishioners that, like Christ, he takes lost souls under his protection. |

In ancient times, to create an omophorion, they took snow-white woolen fabric, the ends of which were embroidered with a pattern in the form of crosses. Later, brocade, silk and other expensive materials were used to make ribbons. The fabric must be chosen in rich and bright colors; for each service there is a cover of a certain color.

The ancient ephod is a prototype of the modern cover

Some historians claim that the progenitor of the omophorion was the ephod. It was worn in ancient times by Jewish clergy. The robe is mentioned in the Old Testament. According to legend, it was worn by Aaron. The ephod was a sleeveless cape that was secured to the shoulders with straps.

A couple of precious stones placed in a gold frame were pinned on the straps. The names of the twelve sons of the patriarch Jacob were engraved on them. Nowadays, instead of them, an image of the crucifixion is applied.