Plot and meaning

The mystery of Easter is sacred and incomprehensible, therefore icon painters do not directly depict the Ascension of the Lord. Easter iconography indirectly points to the main event of the holiday with the help of previous scenes from the Gospel. One of the Easter images is the “Descent into Hell” icon. The image symbolizes the prophecy about the acquisition of immortality by righteous souls, repeatedly mentioned in the Old Testament.

The plot is based on apocryphal, patristic and liturgical works:

- "The Gospel of Nicodemus" of the 2nd century;

- “The Anchor Word”, composed by St. Epiphanius of Cyprus in the 6th century;

- sermons of Eusebius, Bishop of Alexandria, dated to the 5th-6th centuries.

The 12th century icon depicts Jesus and Adam emerging from the Underworld. Christ descends into the Darkness, holding a cross in his hand, and brings out the progenitor.

Later, the authors developed the plot. On a 15th-century Pskov icon, Christ stands at the broken gates of the underworld, with Adam to his right. Behind the back of the progenitor are depicted the figures of kings Solomon, David, other rulers and prophets mentioned in the Old Testament. On the left is Eve. The ancestress knelt before the Savior in repentance. The Old Testament wives follow her. John the Baptist is depicted at the top.

Rarely in icons of Christ's descent into hell are there three righteous wives standing around Eve. One of the righteous women stretches out her hand to the Savior. He reaches out his hand in response, calling to come out of the darkness of the underworld.

On Orthodox icons of the 16th century, angels in red robes appear, Satan defeated by them, and the righteous in white rising from their graves. Artists of the 7th century complicated the “Descent into Hell” icon with a series of marks corresponding to the main memorial days and holidays. A complex image of convergence was placed in the center.

An example of expanded iconography is the Murom Icon. In addition to the key figures of Jesus, Adam, Eve and John the Baptist, on the centerpiece there is an image of paradise, the righteous marching towards it, a prudent thief talking with the forefather Enoch and the prophet Elijah. Two angels with scrolls in their hands hover above.

Ancient icons with a complex plot and a large number of figures serve as models for painting temple images and church paintings.

Hall 4. Dionysius and the Moscow school of icon painting of the 16th century

N.G. Porfiridov. Old Russian art (from the book “State Russian Museum”)

The strengthening of the Russian state in the 16th century, the expansion of its borders, the growth and communication of cities, the revival of trade and political ties with foreign countries - all this contributed to the economic and cultural progress of the country. Interest in understanding the world grew, which was reflected in art. However, along with the approach to life, with some expansion of themes, the appearance of everyday details and entire genre scenes, sometimes even the reflection of advanced social-critical ideas in icon painting, the church-dogmatic, abstract theological side, which delayed the development of art, also intensified. Progressive trends in art were associated with the ideology of the democratic strata of society, whose influence in all areas of Russian life at this time noticeably increased.

The largest artist, almost as famous as Rublev, was Dionysius (c. 1440 - between 1502-1508); the Moscow school, of which he was a representative, had already acquired all-Russian significance.

Dionysius. Icon "Archangel Gabriel" From the Ferapontov Monastery. Around 1500 St. Petersburg, State Russian Museum.

The work of Dionysius differs in many ways from the art of Andrei Rublev. His images do not have such deep inner content; his saints are more refined, more graceful than Rublev’s, but at the same time, more monotonous than them. The art of Dionysius is characterized not so much by the philosophical depth of his ideas as by a tendency towards idealized beauty and external plot entertaining. Hence the greater diversity of scenes and complexity of composition than Rublev’s. The most important thing that is associated with the idea of Dionysius’s painting is the cheerfulness of the worldview manifested in it, the complete absence of a shade of ascetic churchliness. Dionysius's art is bright and joyful. The external expression of these properties was the extraordinary colorfulness of the works, a complex, subtly thought out and masterfully developed palette of colors.

Dionysius. Icon “Gregory the Theologian” From the Ferapontov Monastery. Around 1500 St. Petersburg, State Russian Museum.

the “Archangel Gabriel” belonging to Dionysius himself and his closest assistants.

and

“Gregory the Theologian”

, originating from the Ferapontov Monastery, where Dionysius and his sons around 1500 completed large paintings, including the famous wall painting of the Cathedral of the Nativity of the Virgin.

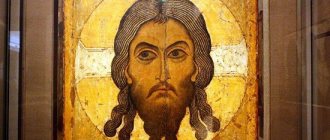

Dionisy's workshop. Icon “Descent into Hell” 1503 St. Petersburg, State Russian Museum.

Icon "Descent into Hell"

, written for the same monastery, has all the advantages inherent in the brush of this master: it is characterized by graceful, slender figures of elongated proportions, with small heads, small hands and feet, and an incomparable “Dionysian” color. The icon delights with its extraordinary richness and variety of colors - blue, pink, golden yellow, pale green, purple, in the finest combination. At the same time, comparing this work with single-story icons of the 14th century, it is easy to notice how much interest in narration and storytelling developed in the work of 16th-century artists, which entailed multi-figure compositions, their complexity with various details and symbolism. The former simplicity and spontaneity (as, for example, in the icons of Novgorod masters) were replaced by verbosity, theatricality, spectacular beauty, and calculated ones. on the one hand, to admire the icon, on the other, to “read” it.

Icon “Cyril of Belozersky in the Life” Late 15th - early 16th centuries St. Petersburg, State Russian Museum.

The icon “Cyril of Belozersky” (on a stand near the window), depicting the founder of the famous largest and richest North Russian monastery, is extremely close to the work of Dionysius. The authentic portrait appearance of Kirill is preserved by an icon painted by his contemporary Dionysius Glushitsky and located in the Tretyakov Gallery. It depicts a simple, stocky, apparently business-like old man. The icon of the Russian Museum represents Cyril in the form of a tall, slender old monk, handsome, with a gentle and wise face. This portrait, idealized and poeticized in the spirit of Dionysius’s work, is distinguished by its exquisitely subtle painting, built on a combination of brown, green and olive tones.

On the large icon “Kirill Belozersky in the Life”

(late 15th - early 16th centuries) the same saint is presented surrounded by scenes depicting individual episodes of his life. The type of icons “in life” or “in deeds” gave special scope to artists inclined to narrative. In twenty small, in comparison with the central figure, pictures (stamps), very vividly arranged, there is a lot of specific content and everyday details: the birth and baptism of Cyril, his tonsure as a monk, the founding of the monastery, Cyril’s “miracles” and even hostile actions of peasants against the monastery who seized their lands.

The desire to depict the surrounding world, of course within the framework of church subjects, is characteristic of the art of the 16th century. Icon themes such as “Every creature rejoices in you, full of grace”, “Let every breath praise the Lord”, etc. are becoming widespread. On the icon “Rejoices in you”

in the center of a very slender, complex composition, in a blue-blue glow, there is an image of the Virgin and Child. Above, the sky is in the form of a blue arc, covering the “highest,” that is, the heavenly, world, with the trees of paradise and choirs of angels. Below is the earth, on it people and “every creature,” that is, every creation, everything living. The theme of the icon reflected an attempt to represent the universe using medieval church and philosophical symbols.

In a slightly different composition of the icon “Every Breath”

the same theme is implemented. Here the artist depicts the whole world as if merged in a pantheistic worldview: humanity - in the person of kings, boyars, ordinary people, men and women, young and old, and all other inhabitants of the earth - animals known and unknown to him: horses, cows, bears, hares , elephants, camels, echidnas, all sorts of plants and flowers, even heavenly bodies - the sun, moon, stars.

The artists' approach to moral and everyday themes was not always of a calm, contemplative nature. The basis of works of fine art were literary and edifying works, which took the form of “parables” and allegories. This kind of original visual “journalism”, in essence, were, for example, wonderful icon-parables: “The Vision of Eulogius”, “The Ladder”, “The Parable of the Blind and the Lame Man”

, which formed parts of a single suite, which has not completely reached us. These “illustrations” of edifying vision stories very clearly and impressively castigated greed, loose morals, and violation of pious vows among the clergy and monasticism. In the context of the vibrant and intense social life of the country in the 16th century, the intense struggle of townspeople and peasants for their rights, the struggle of progressive social thought against the claims of monasticism to own land and people, the responses of art to such topical issues were very relevant. In terms of purely artistic merit, the icons belong to the best examples of painting of the 16th century.

In addition to those mentioned, some more icons of the 16th century are exhibited in the hall, expanding the concept of the Moscow school to which they belong - “Pokrov”, “Andrei the Holy Fool in the Life”

and others.

Read further: Russian Museum. Hall 4. Regional centers of painting and icons of the 17th century

Orthodox depictions of Christ's descent into hell

Since the 10th century, the image of the “Descent into Hell” has been firmly rooted in Russian Orthodox painting and became part of Easter icons. Ancient samples are kept in the State Hermitage, the Moscow Kremlin Museum, the State Russian Museum and the Tretyakov Gallery.

The plot was embroidered on the festive bishop's attire. Among the icons and elements of wall painting, the most famous are four ancient Russian monuments.

Fresco "Anastasis" in St. Sophia Cathedral

The paintings on the walls of the Kyiv Cathedral have partially lost their original appearance. The artists restored the frescoes without a clear idea of the location of the details. The figures of Adam and Jesus, as well as the left side of the image, are painted in oil. In general, the fresco displays the main features of iconography:

- Jesus steps through the ruined gates of hell;

- with his right hand the Savior supports Adam rising from the underworld;

- a cross is depicted in Christ's left hand.

The figures of the prophets Isaiah and Simeon were presumably added to the left during the restoration. Soviet art critic V.N. Lazarev suggested that initially only Eve and the figure of the righteous man were depicted next to Adam.

On the right side of the fragment of the painting, the biblical kings David and Solomon are depicted rising from the sarcophagus. They predicted the coming of Christ, and repeated the prediction while in the underworld. John the Baptist is depicted next to the kings. He points to Jesus as a sign of confirmation of his prediction about the appearance of the Savior in hell.

The iconography of the Sofia fresco is close to the plot of the 12th century icon from the Hermitage. The painting is full of solemnity, especially emphasized in the writing of Jesus Christ.

Prokhor from Gorodets

The icon is located in the Annunciation Cathedral of the Moscow Kremlin and dates back to the end of the 14th century. The author is considered the teacher of the famous Moscow icon painter Andrei Rublev.

Little is known about Prokhor's life. Historians suggest that he was from the Volga city of Gorodets. The characteristic features of his icon painting are sharp transitions from shadow to light. In general, the artist adhered to the styles of the Byzantine and Greek schools of icon painting.

Prokhor participated in painting the walls of the Annunciation Cathedral and, presumably, painted icons for the first iconostasis. The images were lost due to the reconstruction of the cathedral and the fire of 1547. The icons that now stand on the iconostasis are made using the technique of Prokhor from Gorodets, which is why he is called the author.

The Russian master succinctly depicted the convergence:

- under the feet of Jesus there is a crack in the gates of hell and a black abyss;

- Adam is kneeling on the left;

- The Savior and the progenitor reach out to each other;

- on the right, Eva in a red robe is kneeling and also extending her hands;

- Biblical prophets and kings lined up in the background.

Jesus took a step and leaned slightly towards Adam. The appearance of the Savior expresses mercy and forgiveness. Adam is filled with repentance and reverence.

Andrey Rublev

The icon from the Trinity-Sergius Lavra resembles the work of the teacher of the Moscow icon painter, Prokhor from Gorodets.

Features of “Descent into Hell” by Andrei Rublev:

- Christ stretches out his hands to Adam and Eve, standing on the right side of the icon;

- Eve is depicted standing, and Adam kneeling.

Andrey Rublev slightly changed the composition. On the icon of Prokhor, the figure of Adam is traditionally located to the right of Christ, on the left side of the image. The frontal image of the savior is also considered traditional.

On the icon of Andrei Rublev, Jesus Christ is facing to the left, with his back to King Solomon. The biblical king points to the Savior to David. Solomon triumphs - his prophecy has come true.

Dionysius

A follower of the icon painting tradition, Andrei Rublev, depicted the descent of Christ into hell in a cycle of paintings on the walls of the Church of the Nativity of the Virgin Mary at the Feropontov Monastery. The complete cycle is illustrated by an akathist to the Most Holy Theotokos.

The fresco corresponds to the 12th kontakion and literally conveys its meaning: the Savior came to the righteous souls in the underworld and tore the handwriting, wanting to give the Grace of God.

In the performance of Dionysius, Jesus stands on the crossed fragments of the gates of the underworld. Adam and Eve knelt on either side of the Savior. Christ holds their hands. Behind the first parents stand the prophets and kings. Below, under the gate, two angels and Satan, defeated by them, are depicted in the darkness, as well as righteous men in white robes.

5th diary about the Russian Museum.

The reflections of windows and chandeliers - glare - in the Mikhailovsky Palace did not allow me to photograph interesting things as I would have liked. Ancient icons in glass, of course, are preserved in the mode they need, but even viewing them is not so easy. And a regime is definitely needed, both security and inspections. Many of us, of course, would like to have icons in churches, but time and conditions of detention can mercilessly respond to such selfishness. Preserving treasures for posterity is important for believers, and Soviet atheists also lived by this. Just as it is not a hindrance to God whether people love him or not, so it makes no difference to an icon where it is located - this does not diminish its holiness in the least.

I remember standing for a long time in the Moscow Tretyakov Gallery in front of Rublev’s icon “The Descent into Hell.” How else? This is Rublev HIMSELF! And here in front of me is another icon with the same name. There are some things in common, but there are also differences. I remember that Rublev’s style is, as it were, chopped up or something. Strict. Clear. Laconic. And the icon from the workshop of Dionysius (from the Ferapontiev Monastery), who is considered a successor of Rublev and is even called a student - it is softer, the lines are not so sharp, and it seemed to me (I could be wrong) there are more details. The workshop of Dionysius is approximately 1500. This is Dionysius himself and his two sons. Icons and frescoes are their “role”.

The scene of Christ's stay in hell is not described in any of the four Gospels. This is understandable. Mark, Matthew, Luke and John wrote only what they knew. They described what they saw. The memories of witnesses were recorded. How could they know that Jesus visited hell and brought out the righteous and believers? Yes, then they will see Christ again, but this meeting will be short-lived, not long enough for Him to tell them the details. Therefore, only Peter in his epistle briefly mentions that the Savior was in hell. This testimony of the Apostle Peter is enough to see and be convinced that many Old Testament prophecies have come true.

However, the theme of the descent into hell is widespread in Orthodox teaching. What does she rely on? On the recommendation of the Church to know the apocryphal “Gospel of Nicodemus.” By the way, from a Pharisee.)

In the icon, Jesus in a golden vestment brings with him our ancestors - Adam and Eve. Many people will follow - kings and beggars, prophets and harbingers... In the icon they are already higher than hell, but they are still in line. Take a closer look at those to the left and right of Jesus. Look at those who toil in the black abyss. After all, not everyone came out of there, not by a long shot. Many will languish there until the Second Coming, then everyone will come out.

An angel and an archangel bound Satan. They tied, but did not win. The human enemy is still alive, although his strength has become less. The time will come, and there will be a final victory over the devil. It will happen, but we have to wait. It will happen because we believe in it. And we believe because the Lord said so through John. How can you not believe the words of God?

Many passions lead to hell. The icon painter lists them: death, grief, despair, hatred, decline, badness, foolishness, crookedness, enmity, grandeur, sorrow. This is not a complete list; there are more in other sources. By the way, I did not find eight from Orthodox asceticism: gluttony, fornication, love of money, anger, sadness, despondency, vanity, pride. Similar in meaning to passion, but not quite.

Catholics have a slightly different list, but it is also interesting: pride, stinginess, envy, anger, lust, gluttony, laziness or despondency

Wide is the road and great is the gate to hell.

But these passions are overcome by angels in blue robes (there are many of them around Christ) with red spears. The angels hold powers with a list of virtues: happiness, rebellion, love, truth, joy, wisdom, humility, sweetness, reason, belly, purity.

Controversial list? What do you want? The year 1500 after all. As they knew, so they said. Catholics also list virtues:

- Prudence (lat. Prudentia)

- Courage (lat. Fortitudo)

- Justice (lat. Justitia)

- Moderation (lat. Temperantia)

- Diligence (Latin: Industry)

- Patience (lat. Patientia)

- Kindness (lat. Humanitas)

- Humility (lat. Humilitas)

- Faith (lat. Fides)

- Hope (lat. Spes)

- Love (lat. Caritas)

This sequence seemed strange to me. And you? Well, how can faith, hope and love complete the list? How?! Orthodox Christians have no other benefactors except FAITH, HOPE AND LOVE. All the rest just make up these three main ones. However, among Catholics, for example, the same justice may well exist without separate faith, hope, and love. Is that possible? It's more likely that I don't understand it.

This is clearly and specifically stated in the New Testament, in the First Epistle to the Corinthians: “And now these three remain: faith, hope, love; but love is the greatest of these.”

I clearly and for sure know that Faith, Hope and Love - these three can well replace the entire list painted by Dionysius on this icon. Though…

However, I realized that I had a reason to go to the Russian Museum again. I want to take a closer look at which of the virtues (in the opinion of the icon painter) pierces which passion. It’s a pity that I didn’t think of this right away, and the reproduction of the icon is not of sufficient quality to answer my question.

Download icon: link

I would be glad if one of the Aveshniks writes suggestions about which virtue from the icon pierces which of the vices with a spear.

Orthodox prayers

The celebration of Jesus' descent into hell is celebrated on Holy Saturday. Holiday services are held in churches. On the eve of Easter Resurrection, hymns are remembered, announcing the descent of Christ into the underworld. The clergy read the stichera of John of Damascus and the prophecy of Jonah, who perished in the belly of the whale and came out again.

Prayer and troparion are intended for the private glorification of the Resurrection of the Savior.

Prayer to Holy Easter

O Most Sacred and Greatest Light of Christ, Who shone forth more than the sun throughout the whole world in Your Resurrection! In this bright and glorious and saving laziness of Holy Pascha, all the angels in heaven rejoice and every creature rejoices and rejoices on earth and every breath glorifies Thee, its Creator. Today the gates of heaven have opened, and I, having died, have been freed into hell by Your descent. Now everything is filled with light, the heavens are the earth and the underworld. May Your light come into our dark souls and hearts and may it enlighten our present night of sin, and may we also shine with the light of truth and purity in the bright days of Your Resurrection, like a new creation about You. And thus, enlightened by You, we will go forth in luminosity at the meeting of You, who comes to You from the tomb, like the Bridegroom. And as Thou didst rejoice on this bright day by Thy appearance of the holy virgins who came from the world to Thy grave in the morning, so now enlighten the deep night of our passions and dawn upon us the morning of passionlessness and purity, so that we may see Thee with our hearts, redder than the sun of our Bridegroom, and may we hear once again Your longed-for voice: Rejoice! And having thus tasted the Divine joys of the Holy Pascha while still here on earth, may we be partakers of Your eternal and great Pascha in heaven in the unevening days of Your Kingdom, where there will be unspeakable joy and those celebrating the unceasing voice and ineffable sweetness of those who behold Your ineffable kindness. For You are the True Light, enlightening and illuminating all things, Christ our God, and glory befits You forever and ever. Amen.

Icons of the “Descent into Hell” (“Anastasis”) and “Resurrection”

History of the holiday Two iconographic examples related to the theme of the Resurrection of Christ, “The Descent into Hell” and “The Resurrection,” are illustrations of two successive greatest events in gospel history. The first image depicts an event that occurred on the second day of Christ’s stay in the tomb and is remembered by the Church during the service of Holy Saturday, and the second icon directly depicts the very triumph of the Resurrection.

The descent of Christ into hell is one of the most mysterious episodes of New Testament history, which has ambiguous interpretations in modern Christian theology. The essence of this event is that after the crucifixion, Jesus Christ descended into hell, crushing its gates, and, after preaching the Gospel in the underworld, freed the souls of those who listened to Him imprisoned there.

In early Christian writing, the mystery of Christ's descent into hell was reflected, first of all, in the apostolic letters and acts (1), as well as in many apocryphal sources (2). In the Gospel itself, the only mention of the event in question is the words of Christ addressed to the disciples: “As Jonah was in the belly of the whale for three days and three nights, so the Son of Man will be in the heart of the earth for three days and three nights” (Matthew 12:40) .

In modern theology, there are two different points of view on such a fundamental moment of the event under consideration, as the question of who exactly Christ brought out of hell, which can be traced in the Orthodox and Catholic traditions of interpretation of the descent into hell. Orthodox doctrine believes that Christ was followed by all the righteous prisoners in hell, led by Adam, and then by other people who responded to His gospel preaching. Traditional Catholic dogma, on the contrary, insists that Christ, after His death on the cross, descended into hell solely in order to bring out the Old Testament righteous from there (3). It should be noted that this opinion is quite widespread among Orthodox Christians, although this approach is far from the ancient Eastern Christian understanding (4).

The descent of Christ into hell for theologians, poets and mystics of the Eastern Church remains, first of all, a mystery about which nothing can be said definitely and definitively. That is why this topic has received relatively little attention in theological treatises, but it occupies an exceptionally important place in liturgical texts (5).

The event of the descent into hell was followed by the Resurrection of Christ, which occurred early in the morning on the first day of the week. According to the Gospel, the triumph of Christ's Resurrection was accompanied by a great earthquake. The stone from the door of the Holy Sepulcher was rolled away by an Angel, whose appearance was like lightning, and whose clothes were white as snow. The soldiers who stood guard and guarded the tomb, so that none of the disciples would steal the body of Christ, fled in fear. All four canonical Gospels narrate the event of the Resurrection of Christ (Matthew 28:1-15; Mark 16:1-14; Luke 24:1-48; John 20:1-31), since this sacrament is the meaning and basis our faith, in the words of the Apostle: “If Christ has not been raised, our preaching is in vain, and your faith is also in vain” (1 Cor. 15:14).

Establishment of a holiday

Mention of the event of Christ's descent into hell is found in Greek authors of the 2nd-3rd centuries, such as Polycarp of Smyrna, Ignatius the God-Bearer, Justin the Philosopher, Melito of Sardis, Hippolytus of Rome, Irenaeus of Lyons (6), Clement of Alexandria (7) and Origen (8). It should be noted that all the major writers of the “golden age of patristic writing” that followed them (IV century) in one way or another touched on the topic of Christ’s descent into hell, revealing it, first of all, in the context of the doctrine of atonement (Athanasius of Alexandria, Basil the Great, John Chrysostom, etc.).

The Holy Saturday service, which commemorates the event of Christ's Descent into Hell, has retained a number of characteristic features of early Christian worship: the liturgical features of the celebration of this day can be traced back to the 4th century written monument called the “Pilgrimage of Egeria.”

The “Feast of Holidays” and the “Triumph of Triumphs”, the bright Resurrection of Christ (Easter), began in the days of the Apostles. In the letter to the Philippians, a contemporary of the apostles, Ignatius the God-Bearer, there is a mention of the Easter holiday as common in his time. In it, he gives instructions about the prohibition of celebrating it together with the Jews. Evidence has been preserved that initially the Resurrection of Christ was celebrated weekly, and only from the 2nd century did its celebration acquire the character of an annual event.

The Easter service itself took shape in subsequent centuries of Christianity, and its beautiful crown - the inspired Easter canon, sung at Matins, was compiled in the 8th century by St. John of Damascus.

The spiritual meaning of the holiday

In addition to the fact that the teaching about the descent of Christ into hell is one of the most important themes of Orthodox Christology, interpreted as the last stage of kenosis (diminution) that the Lord performed for us, it also has an undoubted timeless, universal significance. The fruits of this event extend not only to those who were there at the time of Christ’s descent into hell, but also to subsequent generations of people.

Quite often in the hymns of the Octoechos one comes across the identification of the entire Church or, even more broadly, all of humanity with those to whom the saving work of Christ at one time extended at the time of His descent into hell. In particular, when it is said that Christ resurrected and brought the primordial Adam out of hell, the name of the forefather here does not mean a specific person, but a symbol of all fallen humanity: “Thou hast risen today from the grave of the Generous One, and thou hast raised us up from the gates of mortals, today Adam rejoices, and Eve rejoices, and together the prophets from the patriarch unceasingly sing of the divine power of Thy power” (Sunday kontakion 3 voices).

Iconography

In the Orthodox iconographic tradition, there was a peculiar mixture of the names of various iconographic types, which can conventionally be called “Anastasis” (Greek “Aνάστασις”), “Descent into Hell” (Latin “Descensus ad inferos”) and “Resurrection of Christ” (the latest iconographic excerpt of the image of the Resurrection).

The iconography of the image of “Anastasis” developed by the 10th century (9). In the 11th century, this version takes its final form in a number of Byzantine mosaics (mosaics of the monasteries of Hosios Loukas (early 11th century), Nea Moni on Chios (1042-1056), Daphne (late 11th century), mosaics of the Hagia Sophia in Kiev (1043-1046). In the center of these mosaic images is Christ with a large cross in his hand, standing on the crossed doors of hell (or the personification of the devil in the form of a pagan god in chains). With his free hand, he extorts Adam from the tomb, behind whom he stands foremother Eve. In the mosaics under consideration, images of kings David and Solomon are necessarily present. In some cases (for example, the Daphne mosaics) a more expanded group of forefathers is represented, led by John the Baptist.

In the 11th century, in Western European art (in miniatures, frescoes, monuments of applied art), the image “Descensus ad inferos” (Descent into Hell) appeared, created precisely as an image of Christ’s descent into hell. In all these images, Christ goes to meet the monster and extends his hand to the people in the monster’s mouth.

In subsequent centuries, in ancient Russian art, under the influence of Western European models, a special iconography of the descent of Christ into hell took place, in general terms reminiscent of the Anastasis editions, but differing from them in a more expanded image of hell and emphasizing the very moment of Christ’s descent. This iconography was later given the name “Descent into Hell.”

There are various versions of this image with the same semantic content. Depending on the location of the figure of Christ in relation to Adam, researchers conventionally identify three main compositional options for this image.

In the first two versions, which are influenced by Roman triumphal images, the figure of Christ is turned towards or away from the ancestors. In the third compositional version, which appeared later, the figures of Adam and Eve are located on either side of Christ, and the Lord stretches out his hands to them. It is this last excerpt in its compositional structure that most closely resembles the image of the Transfiguration of the Lord, which emphasizes the moment of the deification of man. Christ seems to attract Adam and Eve to Himself, drawing them inside the mandorla, which visually expresses the idea of the transformation of human nature, which became possible after the Resurrection of Christ.

In addition to Adam and Eve, the images of the “Descent into Hell” necessarily include King David and King Solomon, as well as John the Baptist, the first New Testament prophet who preached the gospel of Christ in hell. The edition with a frontal image of Christ also has an image of a cross supported by angels in the upper part of the composition, which also introduces an eschatological moment into the ideological content of the image.

Another main idea inherent in this image of the “Descent into Hell” is the idea of the transition from hell to heaven, which is symbolized by the bright contrast of the black abyss below and the golden radiance above. In addition, in some later versions of this excerpt, which appeared in the 15th century, the prophet Moses is depicted in the abyss under the feet of Christ, leading a group of righteous people from hell. In patristic literature, Moses' passage through the Black Sea is interpreted as a departure from slavery to sin to a life of grace in the Promised Land.

Researchers have also noted such a unique feature of the images of the “Descent into Hell” as the rapid movement of Christ, who at the same moment both descends into hell and takes off from it, carrying with him the liberated forefathers. This impression is conveyed by the contrast between the movement of the folds of Christ’s himation, which rose as if during a rapid fall, and the uncontrollable upward rush of the figure of the Savior itself. This seemingly insignificant feature of the compositional structure carries enormous semantic implications. It conveys the idea of the already approaching Resurrection of Christ, which occurred after His descent into the depths of hell.

Finally, the latest image, dedicated to the Resurrection of Christ, is the image of the Savior’s very exit from the tomb. In these images, which appeared in Western European art in the 14th century, Christ is represented with a banner in his hand, standing in the air above an open tomb, near which there are two warriors. In ancient Russian art, this image has been known since the 17th century, where it is most often included in complex compositions of the Resurrection, in which the “Descent into Hell” is presented in the lower part, and “The Descent from the Tomb” in the upper part.

Troparion

Christ is risen from the dead, trampling down death through death, and giving life to those in the tombs.

Kontakion, tone 8

Even though you descended into the grave, O Immortal One, / but you destroyed the power of hell, / and you rose again as the Victor, O Christ God, / saying to the myrrh-bearing women: Rejoice! / and grant peace to your apostles, // grant resurrection to the fallen.

Greatness

We magnify You, / Life-giving Christ, / for our sake, who descended into hell, // and raised everything with you.

Prayer

O Most Sacred and Greatest Light Christ, Who shone forth more than the sun throughout the whole world in Your Resurrection! On this bright, glorious and saving day of Holy Easter, all the angels in heaven rejoice and every creature on earth rejoices and rejoices, and every breath glorifies Thee, its Creator. Today the gates of heaven have opened and the dead have been freed into hell by Your descent. Now everything is filled with light, the heavens and the earth and the underworld. May Your light come into our dark souls and hearts and enlighten our present night of sin, so that we too will shine with the light of truth and purity in the bright days of Your Resurrection, like a new creation about You. And thus, enlightened by You, we will go forth in sacred service to meet You, I will come to You from the grave like a Bridegroom. And just as Thou didst rejoice on this bright day with Thy appearance of the holy virgins, who came from the world to Thy tomb early in the morning, so now enlighten the deep night of our passions and dawn on us the morning of passionlessness and purity, so that we may see Thee with our hearts, the hair redr than the sun of our Bridegroom and yes Let us again hear Your longed-for voice: Rejoice! And having thus tasted the Divine joys of the Holy Pascha while still here on earth, may we be partakers of Your eternal and great Pascha in heaven in the unevening days of Your Kingdom, where there will be unspeakable joy and those celebrating the unceasing voice and ineffable sweetness of those who behold Your ineffable kindness. For You are the True Light, enlighten and illuminate all things, Christ our God, and to You we send glory now and ever and unto the ages of ages. Amen.

Notes

1. In particular, a particularly clear indication of the event of the Savior’s descent into hell is contained in the letters of the Apostle Peter: “For Christ also, in order to lead us to God, suffered once for our sins, the righteous for the unjust, being put to death in the flesh, but made alive in the Spirit , to whom He went and preached to the spirits in prison" (1 Pet. III: 19-20). "For this purpose was preached also to the dead, that they, having been judged according to man in the flesh, might live according to God in the Spirit" (1 Pet. IV:6).

2. In much more detail than in the texts included in the New Testament, the theme of Christ’s descent into hell is revealed in early Christian apocrypha, such as “The Ascension of Isaiah”, “The Testament of Usher”, “The Testaments of the Twelve Patriarchs”, “The Gospel of Peter”, “The Letter of the Apostles” ", "The Shepherd" of Hermas, "The Questions of Bartholomew" (or "The Gospel of Bartholomew"). The most detailed narrative is the text of the “Gospel of Nicodemus,” which contains the entire complex of ideas and images used in Christian literature of subsequent centuries to depict the descent of Christ into hell. According to Nicodemus, Christ does not just descend into the abysses of hell, He invades there, overcoming the resistance of the devil and demons, crushing the gates and tearing off the locks and bolts from them. All these images are intended to illustrate the main idea: Christ descends into hell not as another victim of death, but as the Conqueror of death and hell, before whom the forces of evil are powerless. It is this understanding that will be characteristic of monuments of liturgical poetry devoted to this topic, as well as of Eastern Christian patristic literature.

3. In its commentary on the Apostles' Creed, the Catechism of the Catholic Church says: “The frequent statements in the New Testament that Jesus “rose from the dead” imply that before He rose again He visited where the dead are... Jesus did not descend into hell to not to free the damned from it, or to destroy the hell of condemnation, but to free the righteous who preceded Him.”

In Latin Rite worship, the theme of Christ's descent into hell is used during the Easter period. In the hymn of the proclamation of Easter, which concludes the Liturgy of Light, the first part of the service for the eve of Easter, it is sung: This is the night when, having destroyed the bonds of death, Christ rose from hell victorious (from the rite of the Mass of the Easter period).

4. The teaching that Christ, having descended into hell, “brought out part and left part” is not found either in early Latin or Eastern Christian authors. Both Greek and Latin patristics said either that Christ brought everyone out of hell, or that He brought some (the righteous, saints, patriarchs and prophets, the “elect,” Adam and Eve, etc.), but at the same time, it was not specified whom He did not lead from hell. Indeed, if Christ saved only those to whom salvation rightfully belonged, this would not be an act of mercy, but only the fulfillment of duty.

The liturgical texts dedicated to this event say that Christ’s victory over hell meant the “depletion” of hell, that is, that after Christ descended there, hell was empty, since not a single dead person remained in it. Thus, the authors of liturgical texts perceived the descent of Christ into hell as an event of a universal nature that had significance for all people without exception.

5. The theme of the descent into hell of Christ the Savior is especially often found in the texts of the Octoechos, which contains hymns for weekday and Sunday services, where it is one of the central ones. This theme in the Octoechos is intertwined with the themes of the Savior’s death on the cross and His resurrection, which conveys the idea of the victory of Christ over hell, death and the devil, the “abolition” of the power of the devil and the deliverance of people from the power of death and hell by the power of the Risen One from the dead.

6. Essays “Proof of the Apostolic Preaching” and “Against Heresies.” In it St. Irenaeus says that Christ’s descent into hell “was for the salvation of the dead.”

7. The essay “Stromata”, in which St. Clement expresses confidence that the preaching of Christ was addressed to all who, being in hell, were able to believe in Him.

8. In one of his books “Against Celsus,” Origen writes that when the soul of Christ was freed from the body, he turned his preaching “to those souls who were freed from the body, in order to lead from them to faith in Himself those souls who themselves desired [this conversion], and likewise those to whom He Himself turned His gaze for reasons known only to Him.”

9. The oldest known in our time monuments of the iconographic type “Anastasis” is the high relief of one of the columns of the ciborium in the Cathedral of St. Mark in Venice (VI century). Early examples of images of this type also include, for example, miniatures of the Khludov Psalter of the 9th century.

10. Similar images are presented on the frescoes of the temple in Great Tew (1290, Oxfordshire, England), Danish churches in Kirkerup (1350), Hjembæk (1475), Östruplund (1542). The list can be supplemented by works of famous Western European medieval artists, such as the stamp of Duccio’s Maesta, paintings by Giotto, Sebastiano del Piombo, Jacopo Bellini, Fra Beato Angelico. It should be noted that in Western art history, the term “Christ in Limbo” is usually used in relation to these works, which accurately designates the specific circle of hell where Jesus descended. In these paintings, Jesus is either bending over a hole in the ground, or (in early works, as well as medieval miniatures), hell is depicted as the mouth of a giant leviathan, filled with people.

https://www.portal-slovo.ru/art/46407.php