Sophia of Constantinople

532–537. Istanbul

Sophia of Constantinople. 1910–1915 © Library of Congress Hagia Sophia is the main architectural creation of Byzantium, created by the Asia Minor mathematician Anthimius of Thrall and the architect Isidore of Miletus.

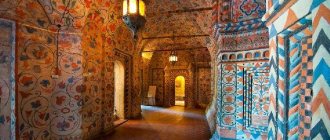

Not just the first temple of the empire, but the center of its church and political life, an integral part of the scrupulous, carefully thought-out court ceremonial, described, in particular, in the treatise “On Ceremonies” by Constantine Porphyrogenitus. Hagia Sophia became the highest achievement of Byzantine architecture, being the heir of ancient architecture. Its idea was formulated in the 15th century by the architect Donato Bramante Donato Bramante (1444–1514), an Italian architect who built St. Peter's Basilica in the Vatican: “The Dome of the Pantheon The Pantheon is a temple in Rome, built in 126 AD. It is a rotunda covered with a hemispherical dome., grew up on the Basilica of Maxentius The Basilica of Maxentius is a temple in Rome, built in 308–312 AD in the form of a basilica: a rectangular structure consisting of three longitudinal naves covered with a stone vault.” Indeed, the brilliant guess of the authors of Hagia Sophia was the idea of merging two architectural ideas of Antiquity: the longitudinal ship of the central nave Nave (from the Latin navis - “ship”) is an elongated rectangular part of the interior, limited by one or two rows of columns and/or a wall. The space of medieval western and eastern temples is often divided into naves, where they came from ancient Greek and Roman architecture. (80 meters long) and the sphere crowning it (a flat, low drum and incredibly wide dome with a diameter of 31 meters) became a single whole: the thrust of the giant dome is “damped” by half-domes resting on powerful, complexly shaped pillars, from which the stone mass falls onto the sails and arches. Thanks to this, the side walls of the building became fragile, completely cut by windows, and the entire interior of Sofia was flooded with light, transforming the stone mass, making it weightless and intangible.

The thin shell of the walls, neutral on the outside (the monotonous Plinth is a wide and flat baked brick), and precious on the inside (gold, natural stones, abundance of natural and artificial light), turned out to be the most important discovery of Byzantine architectural aesthetics and was embodied in a huge variety of forms. And the dome of Sophia became an idea fix of Byzantine and then Ottoman architecture, never repeated by anyone: the project of Justinian’s architects turned out to be too complex and ambitious.

Interior of Sophia of Constantinople. 2000s © De Agostini Picture Library / Getty Images

Immediately after the completion of Hagia Sophia, its dome cracked and then underwent several repairs (the first of which occurred after the earthquake in 557), during which it was strengthened by building buttresses and laying part drum windows. It is not surprising that over time, the appearance of Sofia has mutated greatly: its logical structural frame was hidden by powerful stone risalits - part of the facade protruding at full height beyond its main line, small turrets and all kinds of service premises.

Church of the Holy Apostles (Apostoleion) in Constantinople

VI century. Istanbul

Ascension. In the background is probably the Church of the Holy Apostles in Constantinople. Miniature from the homilies of Jacob Kokkinovathsky. 1125–1150 © Wikimedia Commons

The rulers of the Eastern Roman Empire were characterized by bold ambitions. They are eloquently evidenced by the first Christian building of Constantinople - the so-called Apostoleion, erected by Emperor Constantine I the Great (306-337) at the highest point of the city, at the Adrianople Gate (where the Fatih Mosque now stands). Dedicated to the twelve apostles, the church became the storage place for their relics, as well as the relics of the emperor-builder, whose sarcophagus was erected in the center of the interior - literally illustrating the idea of Constantine's equal-to-the-apostles.

Here is what the historian Eusebius of Caesarea writes about this:

“In this temple he prepared a place for himself in the event of his death, foreseeing with the extraordinary power of faith that after his death his relics would be honored with the names of apostles, and desiring, even after his death, to take part in the prayers that would be offered in this temple in honor of the apostles. So, having built twelve arks there, like twelve sacred monuments, in honor and glory of the face of the apostles, in the middle of them he placed a coffin for himself so that on both sides of this coffin stood six apostles.”

"The Life of Blessed Basileus Constantine"

Two centuries later, under Emperor Justinian, the Church of Constantine was rebuilt, but in general terms retained the original plan. The Apostoleion of the 6th century, a grandiose cruciform temple with five domes, appeared for Byzantium almost the same emblematic image of the temple as Hagia Sophia: for centuries throughout the empire, from Kalat Semana in Syria to San Marco in Venice, his architectural idea inspired Byzantine builders. Apparently, it is he who is depicted on the sheet with the Ascension scene in the manuscript of the homilies of Jacob Kokkinovathsky Around 1125–1150, Vatican..

In the mid-15th century, the Church of the Holy Apostles was demolished by order of Sultan Mehmet II Fatih. We nevertheless know it from many descriptions: Procopius of Caesarea (mid-6th century), Constantine Porphyrogenitus (mid-10th century), Constantine of Rhodes (mid-10th century) and Nicholas Mesarites (about 1200).

Byzantine art: characteristics, history 16 845 Section in the process of filling and correction

Between the edict of Emperor Constantine I in 313 recognizing Christianity as the official religion and the fall of Rome at the hands of the Visigoths in 476, measures were taken to divide the Roman Empire into a western half (ruled from Rome) and an eastern half (ruled from Byzantium). Thus, while Western Christendom fell into the cultural abyss of the barbarian Middle Ages, its religious, secular and artistic values were supported by its new eastern capital in Byzantium (later renamed Constantinople). Along with the transfer of imperial power to Byzantium, thousands of Roman and Greek artists and craftsmen began creating a new set of Eastern Christian imagery and icons known as Byzantine art. It was exclusively Christian art, although the style was borrowed (in particular) from the methods and forms of Greek and Egyptian art, it spread to all corners of the Byzantine Empire, where Orthodox Christianity flourished. Particular centers of early Christian art included Ravenna in Italy, Kyiv, Novgorod and Moscow in Russia. For more information, see also: Christian art, Byzantine period.

The evolution of visual art

For chronology and dates, see here: Timeline of Art History.

General characteristics

The style characteristic of Byzantine art was almost entirely concerned with religious expression; especially with the translation of church theology into literary language. Byzantine architecture and painting (few sculptures were created during the Byzantine era) remained uniform and anonymous and developed within the framework of a rigid tradition. The result was a sophistication of style that little else in Western art could match.

Byzantine medieval art began with mosaics decorating the walls and domes of churches, as well as fresco painting. The effect of these mosaics was so beautiful that the form was adopted in Italy, especially in Rome and Ravenna. The form of public art in Constantinople was icons (from the Greek word "Eikon" meaning "image") - a holy image on a panel or painting - which were developed in the monasteries of the Eastern Church using encaustic, wax paints on portable wooden panels. (See: Icons and Icon Painting) The largest collection of this type of early biblical art is in the monastery of St. Catherine in Sinai, founded in the 6th century by Emperor Justinian. Also note the Byzantine-influenced Gospel of Harim (390-660), the world's oldest illustrated gospel manuscript (from Ethiopia).

Restoring Medieval Art

For more information on the art of Charlemagne and the Ottos, see: Carolingian art (750-900) and Ottonian art (900-1050).

Romanesque era

Romanesque art (1000–1200). For Italian-Byzantine styles, see: Romanesque painting in Italy. For more abstract, linear styles, see: Romanesque painting in France. For signs of Islamic influence, see: Romanesque painting in Spain.

During the period 1050–1200, tensions grew between the Eastern Roman Empire and the slowly resurgent city of Rome, whose popes managed (through careful diplomatic maneuvers) to maintain their power as the center of Western Christendom. At the same time, Italian city-states such as Venice were becoming wealthy through international trade. As a result, in 1204 Constantinople came under the influence of the Venetians.

This led to an exodus of famous artists from the city back to Rome - a reversal of what had happened 800 years earlier - and the beginning of the proto-Renaissance period, exemplified by the frescoes of the Scrovegni Chapel by Giotto di Bondone. However, even as it waned, Byzantine influence continued to be felt in the 13th and 14th centuries, in the Sienese school of painting and the International Gothic style (1375-1450), especially in international Gothic illuminations such as the Magnificent Book of Hours of the Duke of Berry, the brothers of Limburg. See also Byzantine-style panels and altarpieces, including Duccio's Stroganov Madonna (1300) and the Maesta Altarpiece (1311).

Note. For other important historical periods similar to the Byzantine era, see Art Movements, Periods, Schools (from about 100 BC).

Byzantine mosaics (circa 500-843)

Using early Christian adaptations of late Roman styles, the Byzantines developed a new visual language expressing the rituals and dogma of a united church and state. At first, variants flourished in Alexandria and Antioch, but the imperial bureaucracy increasingly took on large commissions and artists from the metropolis were sent to regions that needed them. Founded in Constantinople, the Byzantine style eventually spread far beyond the capital, from the Mediterranean to southern Italy, through the Balkans and into Russia.

Rome, occupied by the Visigoths in 410, was again sacked by the Vandals in 455, and by the end of the century Theodoric the Great had established Ostrogothic rule in Italy. However, in the sixth century, Emperor Justinian

(r. 527-65) restored imperial order in Constantinople, seizing the Ostrogothic capital

of Ravenna

(Italy) as his western administrative center.

Justinian was an excellent organizer and one of the most remarkable patrons of art in the history of art. He built and rebuilt on a huge scale throughout the Empire: his greatest work was the Hagia Sophia

in Constantinople, which employed some 10,000 artisans and workers. The cathedral is decorated with the richest materials the Empire could provide. It is still magnificent, but almost no of the earliest mosaics have survived, so it is in Ravenna that we now have the most impressive remains of Byzantine art from the sixth century. See: Mosaics of Ravenna (c. 400-600).

Inside the dry brick façade of the Church of San Vitale in Ravenna, the congregation is dazzled by a carefully controlled explosion of color blazing against glittering gold. Mosaic art and beautifully textured marble cover almost every wall surface, covering the architecture on which they sit. The gold that fills the background suggests an infinity taken from mortal time, in which supernatural images float. In the apse, shrouded in their distant mystery, Christ and the saints reign dispassionately. However, the two side panels of the mosaic, one depicting the Emperor Justinian with his retinue, and the other opposite his wife Theodora with her ladies of the court. There remains a clear attempt at naturalistic portraiture, especially in the faces of Justinian and Theodora. Even so, their bodies seem to float rather than stand within the tubular folds of their drapery.

In San Vitale and in Byzantine art in general, three-dimensional sculpture plays a minimal role. However, the marble capitals (dating to the period before Justinian) are carved with amazing delicacy, with purely oriental, highly stylized vine scrolls and mysterious animals. A rare example of Byzantine figurative sculpture is an impressionist head, possibly the head of Theodora, which preserves the Roman tradition of naturalistic portraiture.

In the east, the most important surviving work of Justinian is in the church (a little later the Church of San Vitale

)

Monastery of St. Catherine on Mount Sinai

. There, in the great Transfiguration, in the apse, the figures are again important beings, weightlessly suspended in the golden empyrean. The contours, however, are looser and less rigid than those of San Vitale, and the limbs of the figures are strangely articulated - almost an assembly of component parts. This was to become a characteristic and persistent feature of the Byzantine style.

There were other variations in mosaic styles in other places (especially Thessaloniki). Relatively little remains of the cheaper fresco and even less of the manuscripts. Very few 6th-century illuminated manuscripts on purple parchment show a comparable development from classical conventions to strict formality, although pen and ink generally allows greater freedom in structure and gesture. In the famous Raboul Gospel of 586 from Syria, the vivid intensity of the dense imagery may even recall Rouault's twentieth-century work. Relief panels made of ivory have survived; as a rule, these are the covers of consular diptychs. This type of diptych consisted of two interconnected ivory doors with inscriptions. The carvings on the outside, representing religious or imperial themes, have the clarity and detachment characteristic of the best mosaics, and are superbly executed.

In the 8th and 9th centuries, the development of the Byzantine style was catastrophically interrupted in all types of art. Things didn't just stop in their tracks: there was a complete and widespread destruction of existing objects across all Byzantine regions. The visual arts have long been attacked on the grounds that the Bible condemns the worship of images; around 725, the iconoclasts (those who wanted to destroy religious images) defeated those who thought they were justified by issuing the first of a series of imperial decrees targeting images. Heated debates raged on this issue, but iconoclasm

it was also an assertion of imperial power over the church, which was considered too rich and too powerful. It was undoubtedly thanks to the church that some tradition of art was preserved, which flourished again when the ban was lifted in 843.

Byzantine art: revival and development (843-1450)

The end of iconoclasm - a destructive campaign against images and those who believed in them - occurred in 843. The subsequent revival of religious art was based on clearly stated principles: images were perceived as valuable not for worship, but as channels through which believers could channel their prayer and somehow anchor the presence of divinity in their daily lives. Unlike the later Western Gothic Revival, Byzantine art rarely had a didactic or narrative function, but was essentially impersonal, ceremonial and symbolic: it was an element in the performance of religious ritual. The arrangement of images in churches was codified, like the liturgy, and generally adhered to established canons: the great mosaic cycles were deployed around the Pantocrator

(Christ in the role of ruler and judge) is in the center of the main dome, and

the Virgin and Child

are in the apse. Below are the locations for the main events of the Christian year - from the Annunciation to the Crucifixion and Resurrection. Below, again, the hieratic figures of saints, martyrs and bishops lined up in order.

The end of iconoclasm ushered in an era of great activity, the so-called Macedonian Renaissance

. It lasted from 867, when Basil I, the founder of the Macedonian dynasty, became absolute ruler of what was now a purely Greek monarchy, until almost 1204, when Constantinople was sacked. Throughout the empire, and especially in its capital, the decoration of churches was renewed: in the Hagia Sophia in Constantinople, mosaics of enormous size reflected old themes, sometimes with great delicacy and sophistication.

Despite the constant erosion of its territory, Byzantium was viewed by Europe as the light of civilization, an almost legendary city of gold. Literature, learning, and sophisticated etiquette surrounded the Macedonian court; Emperor

In the 10th century

, Constantine VII Porphyrogenitos

sculpted and himself illuminated the manuscripts he wrote. Although his power continued to decline, the emperor enjoyed enormous prestige, and the Byzantine style proved irresistible to the rest of Europe. Even under regimes politically and militarily hostile to Constantinople, Byzantine art was embraced and its medieval artists welcomed.

In Greece, the Church of the Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary at Daphne, near Athens, built around 1100, features some of the finest mosaics of the period: the Crucifixion has a classical sense of great delicacy, and the domed Pantocrator mosaic is one of the most formidable in Byzantine history. churches. In Venice, the vast expanse of San Marco (beginning 1063) was decorated by artists imported from the East, but their work was largely destroyed by fire in 1106, and later work by Venetian masters is in a less pure style. In Sicily, the first Norman king Roger II (reigned 1130–1154) was actively hostile to the Byzantine Empire, but he brought Greek artists who created one of the best cycles of mosaics in the apse and presbytery to Cefalu. The penetration of Byzantine art into Russia began in 989 with the accession of Vladimir of Kiev

marriage to the Byzantine princess Anna and his conversion to Eastern Christianity. Byzantine mosaicists were working at the Hagia Sophia in Kyiv by the 1040s, and Byzantine influence on Russian medieval painting remained decisive long after the fall of Constantinople.

Note: Goldsmithing and precious metals were another Byzantine specialization, especially in Kyiv (c. 950–1237), where Eastern Orthodox goldsmiths took cloisonné (septate) style enamel and enamelling to a new level.

Secular paintings and mosaics of the Macedonian revival have survived little - their most striking manifestation was lost when the legendary Great Palace in Constantinople was burned during the sack of 1204. The remaining works retain distinct classical features - the ivory panels of the Veroli Caskets are an example - such features can also be found in religious manuscripts and in some ivory reliefs (three-dimensional sculptures were banned as a concession to iconoclasts). The Joshua Scroll celebrates the military prowess of the heroes of the Old Testament, reflecting the subjects of Roman columns with relief sculpture, such as Trajan's Column in Rome; the famous Paris Psalter of about 950 is remarkably Roman in both sentiment and iconography: in one illustration the young David, as a music-playing shepherd, is virtually indistinguishable from the pagan Orpheus, and is even accompanied by an allegorical nymph called Melody.

Note: The importance of Byzantine frescoes in the development of Western medieval painting should not be underestimated. See, for example, the very realistic wall paintings in the Byzantine monastery church of St. Panteleimon in Gorno Nerezi, Republic of Macedonia.

In 1204, Constantinople was sacked by the Latin Crusaders and they ruled the city until 1261, when the Byzantine emperors returned. Meanwhile, the craftsmen migrated to other places. In Macedonia and Serbia, fresco painting had already been created and this tradition continued steadily. About 15 main cycles of frescoes, mostly by Greek artists, have survived. The frescoes undoubtedly encouraged a fluency of expression and emotional feelings that are not often displayed in mosaics.

The last two centuries of Byzantium, in its decline, were troubled and war-torn, but surprisingly led to a third great artistic flowering. The fragmentary but still impressive Deisis in the Hagia Sophia in Constantinople may have been built after Latin rule rather than in the 12th century. He acquired a new tenderness and humanity, which was continued - for example, in the magnificent cycle of the early 14th century of the monastery church of Christ in Chora. A distinctive style has developed in Russia, reflected not only in such masterpieces as Rublev’s icons, but also in individual interpretations of traditional themes by Theophanes the Greek. Byzantine emigrant who worked in a dashing, almost impressionistic style in the 1370s in Novgorod. Although the central source of the Byzantine style was extinguished by the Turkish conquest of Constantinople in 1453, its influence continued in Russia and the Balkans, while in Italy the Byzantine style (mixed with Gothic) survived into the era of pre-Renaissance painting (c.1300-1400) , discovered by the works of Duccio di Buoninsegna (c. 1255-1319) and Giotto (1270-1337).

Byzantine icons

Icons, generally small and easily transportable, are the most famous form of Byzantine art. There is a belief that the first icon was painted by St. Luke the Evangelist; it depicts the Virgin pointing to the Child on her left hand. However, no examples are known to date from before the 6th century. Icons became increasingly popular in Byzantium in the 6th and 7th centuries, to some extent accelerating the iconoclasm reaction. Although iconoclasts claimed that icons were worshiped, their true function was to aid in meditation; through a visible image the believer could comprehend invisible spirituality. Concentrated in a small iconostasis, they served the same function in the home as the mosaic decorations of churches - signaling the presence of divinity. The production of icons for Orthodox churches has never stopped.

Thus, the dating of the icons is rather speculative. A recent discovery at the Monastery of St. Catherine on Mount Sinai is a series of icons that could be arranged chronologically with some confidence. There are many different styles available. Early Saint Peter is distinguished by its frontal simplicity, the direct gaze of wide-open eyes, which is found again and again in single-figure icons. He also has an almost suave elegance and dignity combined with a painterly energy that gives the figure a distinct tension. There is a similar emotional quality in the well-preserved Madonna and Saints, despite the symmetry and rather rough sculpting. Both were probably from Constantinople.

Immediately after the iconoclastic period, religious images made of richer materials, ivory, mosaics or even precious metals, were perhaps more popular than painted ones. From the 12th century icons began to appear frequently and one great masterpiece can be dated to 1131 or shortly before. Known as the "Vladimir Mother of God", it was sent to Russia shortly after it was painted in Constantinople. The Virgin still points to the Child as the embodiment of the divine in human form, but the tenderness of the pose, cheek to cheek, is an illustration of the new humanism.

Since the 12th century, the subject matter of icons has expanded significantly, although long-established themes and formulas important for the convenience of believers have been preserved. The heads of Christ, the Virgin and the patron saints continued, but action scenes appeared - especially the Annunciation and the Crucifixion. Later, composite panels containing many subject scenes were painted for iconostases, or choir screens. Long after production ceased in Constantinople with the Turkish conquest, it continued and developed in Greece and (with clearly distinguishable regional styles) in Russia, as well as in Serbia, Romania and Bulgaria.

In Russia, individual masters appeared even before the fall of Constantinople, along with such important centers as the Novgorod school of icon painting. The most famous Russian icon painter was the monk Andrei Rublev (c. 1370-1430), whose famous masterpiece, the Icon of the Holy Trinity (1411-25), is the best of all Russian icons. He surpassed the Byzantine formulas and manners of the Novgorod school, founded by the Byzantine refugee Theophanes the Greek. Rublev's icons are unique for their cool colors, soft shapes and quiet radiance.

The last of the great Russian icon painters of the Novgorod school was Dionysius (c. 1440–1502), famous for his icons for the Volokolamsk Monastery and the Deesis for the Assumption Cathedral in Moscow. In fact, he was the first known figure of the Moscow school of painting (circa 1500-1700), whose Byzantine icons were created by such masters as Nicephorus Savinus, Procopius Cyrinus and the great Simon Ushakov (1626-1686).

We gratefully acknowledge the use of material in the above article from David Piper's outstanding book, An Illustrated History of Art.

- Photobookfest will take part in Cosmosow

- The architecture of Byzantium is a reflection of divine beauty

- The emergence of icon painting

Church of Simeon the Stylite (Kalat-Seman)

475 Aleppo

Basilica of the Church of Simeon the Stylite. Syria, first half of the 20th century © Library of Congress

In the 5th century in Eastern Syria, near Aleppo, lived Saint Simeon, who discovered a special type of asceticism - standing on a pillar. Renouncing the worldly in every possible way and caring about the mortification of the flesh, the monk was subjected to countless temptations, partially described in Luis Buñuel’s film “Simeon the Hermit.” Having spent several decades at an altitude of 16 meters, Simeon was honored by Christians from all over the world, including Persians, Armenians and the British.

Around that same pillar, which exists to this day (Byzantine miniaturists loved to depict Simeon’s pillar as a column with a capital, completed with an elegant balustrade, inside which the saint himself was located; sometimes a ladder was attached to the column), in the 80-90s of the 5th century there was A monastery complex was erected, the grandiose design of which found its equal only among the imperial ensembles of late Rome.

The octagonal core of Kalat Semana (translated from Arabic as “Simeon’s fortress”) is surrounded by three arms. Together they form a spatial cross, almost the same as in the Church of the Holy Apostles in Constantinople. Now the temple is in ruins, and what it exactly looked like immediately after construction is unknown, but thanks to the testimony of Evagrius Scholasticus, we know that the central core, which contained the pillar of Simeon, remained open.

Following Kalat-Seman, a whole architectural movement of the 5th–6th centuries arose, represented by the churches of Simeon the Stylite the Younger on the Wondrous Mountain, John in Ephesus and the Prophets, Apostles and Martyrs in Gerasa.

Barberini diptych

VI century. Louvre, Paris

© Marie-Lan Nguyen / Wikimedia Commons

The late antique imperial diptych originally consisted of two ivory tablets, on one side polished and covered with wax (they were marked with a steel stick, style), and on the other, decorated with an ivory relief inlaid pearls. Only one panel of the Barberini diptych (named after its 17th-century owner) has survived. It represents the triumph of an emperor (which one is unknown: possible contenders are the emperors Justinian, Anastasius I or Zeno), whose head is crowned with a palm branch by an allegorical figurine of Nike, the goddess of victory. The Emperor sits on a horse and raises a spear, and at his feet lies the generous, fruit-bearing Earth (in the figure of which art historian Andre Grabar Andre Grabar (1896–1990), a Byzantineist, one of the founders of the French school of Byzantine art history, saw a hint of the universal role of Byzantine art. emperors).

According to imperial iconographers and panegyrists, the enemies of the basileus were like wild animals. Therefore, in the Barberini diptych, trampled barbarians, dressed in exotic clothes, march in the same column with elephants, lions and tigers to present their gifts to the triumphant. Absolutely antique iconography, which has adopted the only sign of the new era - the image of Christ crowning the scene of the imperial triumph.

The Barberini diptych is one of the most brilliant and technically advanced works of art of the 6th century. After Emperor Justinian, such diptychs ceased to be in use, but even among the surviving objects there is hardly a copy as luxurious, intricate and finely executed.

Vienna Genesis

First half of the 6th century. Austrian National Library, Vienna

Rebekah and Eliezer at the well. Miniature from Vienna Genesis. 6th century © De Agostini Picture Library / Getty Images

In addition, the oldest well-preserved illustrated manuscript of the Bible dates back to the 6th century. It contains a fragment of the text of the Book of Genesis written on purple with silver ink - an expensive rarity, clearly indicating the royal origin of its owner.

Each page of Genesis is decorated with miniatures. Some of them have the form of friezes (the plots on them are not chronologically connected), while others are built like a picture and are framed: if there was no need for compositionally independent miniatures in the scroll, it arose during the transition to the codex book.

Like the Barberini diptych, the painting of the Viennese Genesis is full of ancient allusions and is reminiscent of the paintings of Pompeii: this is served by graceful columns, porticoes and airy velums Velum (from the Latin velum - sail) - a curtain, bedspread, usually depicted as arched. Images of velums are common in icon painting, but go back to Antiquity, allegorical figures of sources and bucolic motifs. Early Christian painting was in no hurry to part with its Roman past.

Icon of the Mother of God with Saints

VI–VII centuries. Monastery of Saint Catherine, Sinai

© Wikimedia Commons

Antique ideas about the image also dominate early icons, for example, the icon with images of the Mother of God and Child and holy martyrs from the collection of the Sinai monastery. The images of Mary seated on the throne, Christ and two angels are still sensual and spatially reliable in the ancient way, and their faces (or rather, faces) are emotionally neutral and filled with calm.

On the contrary, the martyrs (possibly the holy warriors Theodore and George - based on the typical similarity with their later codified portraits) with golden crosses in their hands (as a sign of their martyrdom and posthumous glory) are painted in such a way that very soon, when the iconoclastic disputes are completed, they will decide in the East -Christian icon painters and theologians. Hidden by luxurious mantles, their figures resemble appliqués; small symbolic legs are placed as if the bodies were suspended in the air, and the faces (already faces, not faces) are stern, motionless and numbly looking forward: what for life-loving Antiquity is sheer boredom, for Byzantium is a spiritual ideal based on self-renunciation.

The icon was painted with wax paints (like the few other surviving contemporaries from the collection of the Sinai monastery and the National Museum of Art named after Varvara and Bogdan Khanenko in Kyiv). Painting with wax paints, which had disappeared from the practice of icon painters by the 8th century, made it possible to paint “hot” (when the next layer of paint was applied to the already dried lower one). Thanks to this, the paint surface kept the strokes visible, essentially conveying the movement of the brush, the handwriting and manner of the artist. Such spontaneity subsequently turned out to be inappropriate for developed theological ideas about the iconographic image.

Byzantium

The oldest mosaic of Byzantium dates back to the 3rd-4th centuries. AD The golden age of this technology falls on the VI-VII and IX-XIV centuries. AD Given the high cost of materials and work, the main customer of Byzantine mosaics was the Catholic Church. Magnificent ancient mosaics have been preserved in churches in Italy (in Ravenna, Montreal, Cefalu) and Turkey (in the Hagia Sophia in Istanbul). The main motives are biblical stories.

Byzantine mosaic is a standard, it is characterized by high artistic skill. The images are accurate, preference is given to large canvases, the effect of scale is taken into account: the distance of the viewer, his location. A distinctive feature of the drawing is the presence of a contour for each depicted object. The purpose of the technique is to visually highlight an element against a general, often golden, background when viewed from a long distance.

Mosaic "Christ Pantocrator". Cathedral of the diocese of Cefalu (Italy, Sicily). 1145-1148

What does smalt look like?

The craftsmen used smalt - colored glass - in their work. The technology is based on adding metal oxides to glass, which give the tiles the required color. The workshops produced up to several hundred different shades. Material for mosaics in Byzantium was very expensive. To create panels, they resorted to smalt with the addition of gold leaf, and mixed in copper and mercury. The technology is characterized by the density of the arrangement of plates (small squares, less often of a different shape) and the use of a direct set when laying them. The finished canvas has an uneven surface and a characteristic shine.

Khludov Psalter

Mid-9th century. State Historical Museum, Moscow

Iconoclasts John the Grammar and Bishop Anthony of Silea. Khludov Psalter. Byzantium, approximately 850 © rijksmuseumamsterdam.blogspot.ru

The Khludov psalter, named after Alexei Ivanovich Khludov, who owned the manuscript in the 19th century, is one of three surviving psalters created in the Studite monastery of Constantinople shortly after the restoration of icon veneration (after two centuries of literal oblivion of the pictorial art, during the years 726–843, anthropomorphic images of Christ and saints remained illegal). This manuscript (the so-called monastic edition of the psalter with illustrations in the margins) is the most complete of the three and the most abundantly illustrated.

The most telling feature of her miniatures is the artistic response to recent events. The illustration for Psalm 68:22, “And they gave me gall for food, and in my thirst they gave me vinegar to drink,” depicts two iconoclasts dipping the sponges at the ends of their spears into lime to smear the face of Christ with them. Their long, standing hair brings to mind medieval depictions of the devil, who traditionally wore a similar hairstyle. On the same page there is an explicit comparison of the iconoclasts with those who crucified Christ (the same movements and objects in their hands), which leaves no chance for rehabilitation for the former - their faces, so hated by the medieval reader of the manuscript, were scraped out.

Minology of Vasily II

Beginning of the 11th century. Vatican Library

20 thousand martyrs of Nicomedia. Miniature from the Minology of Basil II. The beginning of the 11th century © Wikimedia Commons

The 10th–11th centuries in Byzantium became the time of great hagiographic hagiography - a set of lives of saints and other genres dedicated to the life and work of saints, such as miracles, martyrdoms, etc. projects like minology Minologies are a collection of the lives of saints, arranged in the order of their commemoration during the liturgical year (September to August). Symeon Metaphrastus, stylistic unification of hagiographic texts and compilation of collections free from pre-iconoclast marginal subjects.

The manuscript, now kept in the Vatican, was intended as a luxurious illustrated collection of the lives of saints, presented to Emperor Basil II the Bulgarian Slayer (976–1025). Each life takes up only 16 lines per page, while the rest of the page is devoted to miniatures. This is a unique case for Byzantine book writing of the subordination of text to image: the miniatures were written first (on several pages the text area remained empty). The code preserved the names of eight artists who worked on the creation of 430 illustrations - unprecedented material for analyzing not only the handwriting of the masters, but also the question of their cooperation within the artel.

The Minology of Basil II is a brilliant example of mature Byzantine art: in miniatures with portraits of saints and scenes of their martyrdom, a delicate balance was found between the imitation of reality, characteristic of Antiquity, and medieval convention and asceticism. Natural forms characteristic of nature turn into geometric ones; soft halftones - in golden assist Assist - lines applied in gold over the paint layer. Symbolizes divine light.; faces with individually specific features - into frozen symmetrical faces.

Mosaics and frescoes of the monastery of Hosios Loukas in Phokis

Around 1040. Greece

Baptism. Mosaic of the nave in the monastery of Hosios Loukas. Phokis, 11th century © Wikimedia Commons

This artistic movement reached its apogee in the ensemble of the monastery of Hosios Loukas (St. Luke) in Phokis. Its katholikon (main temple) and crypt (underground room) have preserved amazing mosaics and frescoes from the 40s of the 11th century - the time of the so-called ascetic style, popular not only in monasteries, but also among provincial princes (the mosaics and frescoes of St. Sophia of Kyiv were made in that same manner). It can be assumed that this aesthetics was formed in the artistic circles of Constantinople: this is indirectly indicated by the exceptional quality of performance of the Greek ensemble.

On the shining golden background of the dome of the Hosios Loukas katholikon, the descent of the Holy Spirit on the apostles is represented - quite rare iconography in Byzantium, glorified in the descriptions of the Apostoleion of Constantinople.

The descent of the Holy Spirit on the apostles. Mosaic in the monastery of Hosios Loukas. Phocis, 11th century © Wikimedia Commons

Not following nature, the mosaicists of Hosios-Lukas reduce the figures of saints almost to symbols, emphasizing only the most significant details - the characters’ gestures and their huge identical frozen eyes. The skillful marble cladding of the walls demonstrates the Byzantine understanding of the hierarchy of architecture: evangelical scenes and images of saints on a golden background hover at the level of the vaults, while the lower planes of the walls are occupied by an abstract pattern of natural stone.

Among the rarities of Hosios Loukas is the crypt under the katholikon, the burial place of St. Luke, painted simultaneously with the katholikon itself with frescoes depicting the feasts and passion of Christ. A significant place in the paintings of the entire ensemble is occupied by images of saints, many of whom are monks, including locally revered ones (Luke Gurnikiot, Nikon Metanoit, Luke Styriot). The monastic and local character of the temple's decoration program is combined with a high-born capital order: the founder of the monastery was Emperor Romanus II (died 963).

Grandiose for its time, the Hosios-Lukas project is an example of the Middle Byzantine synthesis of architecture, painting and sculpture, creating the ideal iconographic scheme of a cross-domed temple.

Historical information

Ancient people became famous for their ability to put together a whole image from individual colored pieces. Such art appeared in many countries and developed to perfection. In Rome, mosaics were used to decorate the floors and walls of public buildings, baths and palaces. Pebbles and smalt were used to create paintings . This material is a mixture of glass and metals - copper, gold, mercury. Thanks to them, different shades of smalt were obtained.

But the masters of the Byzantine Empire were more skillful than the Roman ones. She created her own technology for laying out mosaics. At first, they used much smaller pieces, which made the work more sophisticated. Later the composition of smalt was changed. Glass began to be mixed not only with metals, but also with other substances. This made it possible to obtain a larger range of colors. The quality of the work was so high that to this day the mosaics have been preserved in their original form.

Roman and Byzantine masters performed works on different themes. The first depicted everyday scenes, the second focused on biblical scenes and religious stories. This type of art in Byzantium was used mainly for decorating temples. Each panel was huge, monumental.

Emperor Roman's Chalice

10th century Treasury of the Cathedral of San Marco, Venice

© De Agostini Picture Library / Getty Images

The chalice (a liturgical vessel used to consecrate wine and receive the sacrament) was one of the treasures brought from Constantinople to Venice by the Fourth Crusade in 1204. Made of sardonyx, gilded silver, pearls and cloisonné enamel, this chalice was the contribution of a certain Byzantine emperor to one of the capital's churches: on the base of its stem is engraved an inscription asking for God's help to the emperor, described in the epithets “faithful” and “orthodox”. This emperor is believed to have been Romanus I Lecapinus (920–944), who ascended the throne after Leo VI (886–912).

In the upper part of the vessel there are fifteen enamel plates framed with pearl threads. They feature half-figures of Christ, John the Baptist, the Mother of God, the evangelists and the Fathers of the Church - in essence, a painting of the church in miniature - preserving both its central images and their hierarchical structure.

Holy Crown of Hungary

1074–1077. Parliament Palace, Budapest

1 / 3

© Wikimedia Commons

2 / 3

© Wikimedia Commons

3 / 3

© Wikimedia Commons

The compositional center of the crown is decorated with enamel plates with images of Christ and Emperor Michael VII Duca (probably intended for another, unknown object presented by the Byzantine basileus to the ruler of Hungary and later incorporated into the crown). On one side of the crown sits Christ, surrounded by the archangels Michael and Gabriel and several saints (George and Dmitry, Kozma and Damian), with their faces turned to the King of Heaven. On the other side of the crown, as if reflecting its frontal part, on either side of the Byzantine autocrat sit his son Constantine and King Geza I of Hungary. They look at the basileus with the same kind of humility and submission as the saints look at the Supreme Judge.

According to Byzantine panegyrists, the appearance and regalia of the Roman emperor were visible proof of his greatness and merits, just as his figure and movements embodied the ideal of brilliant beauty. It is curious that, in addition to Michael VII himself, the archangels are dressed in the imperial dress on the Hungarian crown - this is a visual continuation of the oratorical tradition of likening emperors to angels (for example, Michael Psellus in his panegyric to Constantine IX Monomachus compares the essence of the emperor with the immortal forces of heaven, and Michael Italik in one of in his speeches he calls John II Komnenos “an angel of the Lord, sent down to pave the way against the enemy”).

The Byzantines' ideas about the two courts, the earthly one of Constantinople and the imaginary heavenly one, were not mirrored: the emperor is compared not with Christ, but with angels, and only Christ sits on the throne, while the emperor and all his overlords are depicted shoulder-length. The clear expression of the hierarchy of power, given by the Byzantine artist, fixed the idea of the position of the Byzantine monarch exactly in the middle between Christ and other earthly rulers.

Icon "Ladder"

End of the 12th century. Monastery of Saint Catherine, Sinai

© Wikimedia Commons

One of the most popular books among the Byzantines was the instructive work of the 7th century “The Ladder” by John Climacus: describing monastic virtues and vices in his words of instruction, John painted an image of the monk’s spiritual ascent to God. The text of “The Ladder” served as the basis for the iconography of the same name, which developed in the 11th century and became extremely popular in the Middle Byzantine period. Its most famous example is the Sinai icon from the late 12th century. Thirty steps of the ladder (according to the number of words of instruction) form the semantic center of the composition: the monks, led by John Climacus and Archbishop Anthony (possibly the head of the Sinai monastery, for which the icon was painted), ascend to Christ, while some members of the brethren, unable to withstand the temptation , fall into the black mouth of hell. An icon of exceptionally high quality could have been created both in Sinai and in Constantinople. Its local origin is evidenced by its reverse, decorated with crosses placed in a circle and the inscription “Jesus Christnik” (from Greek - “Jesus Christ conquers”) - similar images are present on several other 12th-century monuments from the monastery’s collection.

An ideally balanced composition (two diagonals formed by a staircase on one side and monks and angels with covered hands, witnesses of a monastic feat, looking at each other, on the other), subtlety of writing (the “gold on gold” technique, in which the golden background is enlivened by shimmering, as if halos and disks were bathed in mystical light), the image of ascetic righteousness and difficult ascent to eternal life embodied in the icon make the “Ladder” one of the perfect creations of mature Byzantine art.

Modern Art

Byzantine masters set a worthy example to their contemporaries. Their creative journey continues today. The mosaic technique has become not just a calling card of the state, but also an example of classical art.

Many famous artists of the 21st century rely on the knowledge of ancient masters. They use the same names and definitions, techniques for mixing smalt and laying out glass. Some Orthodox churches are decorated according to the canons of the Middle Ages. And in one of the centers for the study of ancient cultures - the Art Academy of Ravenna - there is a class on the ancient art of mosaics. Experts from all over the world come here to listen to lectures and participate in seminars. Graduates are able to make copies of famous Byzantine paintings and restore images.

Today you can see ancient examples in Istanbul and Italy. Local cathedrals and mausoleums are decorated inside with magnificent mosaics. The oldest examples of Byzantine images are found in Ravenna and Hagia Sophia. And you can also find panels in some churches in Kyiv; the masters of Rus' also borrowed ideas from the Byzantines.

Frescoes of the Church of St. George

1191 Village Kurbinovo, Macedonia

1 / 3

Archangel Gabriel. Fresco of the Church of St. George. 12th century © Wikimedia Commons

2 / 3

Our Lady. Fresco of the Church of St. George. 12th century © Wikimedia Commons

3 / 3

Saint George. Fresco of the Church of St. George. 12th century © Wikimedia Commons

The frescoes of a small rural church on Lake Prespa reveal qualities that unexpectedly became leading in Byzantine painting of the end of the Komnenian era (more precisely, the time of the dynasty of Angels, 1185–1204): emphasized dynamics, tension, excitement of images and at the same time - subtle psychologism and a variety of emotional states . These purposes are served by the violent, impulsive movements of the characters, their active gestures, and the foaming folds of their clothes. Some distortion of features is noticeable in the faces: small strokes, light and shadow tints, elongated, slightly narrowed ovals, low foreheads and long noses, creating the impression of melting plasticity. The exaggerated antique principle, based on the desire to imitate nature, is also manifested in the abundance of profile images, the oversaturation of compositions with staffage figures .

This style, called Byzantine mannerism, constituted an exceptional phenomenon of Byzantine painting. The complex artistic searches of the late Komninov period reached their exhaustive expression in the frescoes of Kurbinovo.

Already in the 1190s, this art coexisted with a completely different imagery, much more typical and familiar to Byzantium: with a classical structure and an artistic language operating with the concepts of harmony, balance and pure forms. This style would become leading throughout the 13th century.

The use of frescoes in a modern interior

Fresco nowadays is a rather expensive and therefore “elite” way of interior decoration. A room with painted walls can resemble an ancient villa, palace, or the possessions of rich and prominent people of the Renaissance. At the same time, however, modern fresco does not experience restrictions either in the choice of subject, or in style, or even in execution technique. The image can be futuristic, humorous, or can imitate classical forms.

1 / 4

An interesting example of contemporary art is the Denver murals. The mural at this city's airport, created by Leo Tanguma, shows scary images. These works were written to warn humanity; you can understand them as a certain form of social advertising.

Frescoes of the Church of the Ascension

Until 1228. Milesevo Monastery, Serbia

1 / 2

White angel. Fragment of a fresco from the Mileshevo monastery. Early 13th century © Wikimedia Commons

2 / 2

Sava I of Serbia. Fragment of a fresco from the Mileshevo monastery. Early 13th century © Wikimedia Commons

When the Byzantine Empire was under the rule of the Latins, alternative artistic centers grew on its outskirts, among which the Serbian state turned out to be very significant, willingly recruiting Byzantine artists who were left out of work in their homeland. The frescoes of the Mileshevo monastery were probably created by one of these artels - craftsmen invited by King Vladislav to Serbia from the devastated Byzantium. Imitating the Constantinople models, Mileshevo artists imitated the effect of a mosaic: on the golden backgrounds of the frescoes they created a pattern of squares reminiscent of smalt cubes.

Mileshevo’s absolute masterpiece is the so-called white angel in the scene of “The Myrrh-Bearing Women at the Holy Sepulcher,” captivating with her physical beauty, softness of features and natural resemblance. His face is painted in thick strokes, with a bright blush and large, regular features. A three-quarter turn of the head in contrast to the position of the body creates the effect of energetic, spontaneous movement.

Compared to the dramatic late Komnenian painting, the art of Mileshevo is perceived as chamber-like, subtly spiritual and lyrical. Less concerned with detail, such painting is based on the obvious role of the protagonist, subordinating the chorus of secondary characters. Statuary and emphasized on a large scale, the angel of Mileshevo is addressed directly to the viewer, pointing him to the miracle of resurrection that has occurred.

Mosaic technology

The main achievement of the Byzantines in mosaic technology was that they learned to give glass pieces any shape . But most often we tried to use squares and rectangles. Circles and ovals are rarely found in images.

Direct set is a feature of the Byzantine mosaic technique. The smalt cubes were not polished; they were laid out in a row close to each other. The origin of small parts is associated with an increase in the level of craftsmanship. Small cubes allow you to accurately depict facial features, make the picture more elegant and achieve a soft transition of colors. Artists of Italian nationality created rough panels; Byzantine ones are distinguished by the refined laying of faces, clothing, and skillful depiction of the play of light and shadow.

Another difference from the masters of other countries is the golden background. Thanks to this technique, the paintings lie a little unevenly, which gives them a specific sheen. At the same time, the proportions of the figures are respected, although all faces are made according to the same standard. It can still be seen today on icons and other images of saints.

Mosaics and frescoes of the Chora Monastery (Kahrie-Jami)

Around 1315 - 1321. Istanbul

1 / 5

Facade of the Church of Christ the Savior in the Fields. Photo from the 1990s © Wikimedia Commons

2 / 5

Dormition of the Virgin Mary. Mosaic in the Chora Monastery © De Agostini Picture Library / Getty Images

3 / 5

Dome of the parekklesion in the Church of Christ the Savior in the Fields © Wikimedia Commons

4 / 5

Southern dome of the esonarthex. Genealogy of Jesus Christ and Christ Pantocrator. Fresco from the Chora Monastery © Wikimedia Commons

5 / 5

Detail of the Last Judgment fresco in Chora © Wikimedia Commons / Vladimir Lukic

The Chora is perhaps the most studied monument of Byzantium - the last grandiose ensemble of the Byzantine capital, created through the efforts of the great logothete. The great logothete is the highest official of the royal office, the head of Byzantine diplomacy, in fact, the prime minister of the empire. Theodore Metochites. At the expense of this nobleman, the dome of the main building was restored, and the narthex was also erected. The narthex is a room at the entrance to the temple, adjacent to its western wall . and parekklesion Parekklesion is a chapel attached to the temple.. His portrait with an exact model of the building in his hands is located in front of the entrance to the temple - kneeling, dressed in oriental costume in the fashion of that time, the customer stands before the image of Christ, accompanied by the epithet “Hora ton zonton” (that is "Land of the Living")

The mosaics of the Chora have survived only partially, but they eloquently testify to the theological education and sophistication of the compiler of their program. The main volume of paintings is presented in the narthex, where the story of the Mother of God is told, and the exonarthex, where the story of the birth of Christ is depicted. In the vaults of the same rooms there is a third cycle of mosaics, depicting the earthly ministry of the Savior - miracles and parables (for example, the Miracle in Cana of Galilee and the Multiplication of the Loaves). Finally, the main theme of the parekklesion, which preserved the fresco cycle with the famous image of the Descent into Hell in Vima Vima - the eastern part of the temple, in which the altar is located, is the image of the Resurrection and the Last Judgment: the sarcophagi of Theodore Metochites himself and his contemporaries - the Conostavl Conostavl - were to be placed here - commander of the troops. Mikhail Tornik with his wife.

The mosaics and frescoes of Chora are a brilliant example of the art of the era of the so-called Palaiologan Renaissance - a cultural rise that occurred during the last dynasty of Byzantine emperors, who ruled in the mid-13th - mid-14th centuries. Each scene is decorated with exquisite architectural backdrops with porticos, columns, velums and airy canopies thrown over them, and landscape motifs such as a lonely tree. The compositions abound in moving, tightly draped figures, often in contrapposto poses and bold turns, and staff elements, the diversity of which adds an element of genre to the scenes. At the same time, each detail serves a special organization of the composition, establishing a rhythm within it, immediately fixing the viewer’s attention on the key moment of the plot.

For example, the scene in which Mary and Joseph appeared before King Herod at the time of the census. Its main characters are obvious thanks to the architectural verticals of the background. At the same time, the eye immediately grasps the image of Mary, because it is to her that the characters on the left are turned, arranged at skillfully selected intervals; An additional accent is brought by the tree in the background, its outline repeating the slope of Mary’s body.

Stages of creating a fresco

Before creating a piece, it is necessary to prepare the surface. The standard number of layers of plaster is two. The basis of plaster for frescoes is slaked lime mixed with sand in a certain proportion. An additional layer is applied to the main layer; this is a very thin layer - 3 - 5 millimeters. As long as the top layer remains wet, you can write on it.

You need to prepare a template in advance. This could be a regular drawing. The template is applied to the surface and the contours are pressed in (graphics) - this can be done, for example, with a pencil. Another option was also used: tracing paper with cut holes was removed from the template, and contours were drawn through them with charcoal directly onto the wall. Italian Renaissance masters sometimes enhanced contours with sanguine, a special rimless pencil.

1 / 3

Now you can start painting. Often, the artist first applies the so-called underpainting, that is, paints over certain areas with gray color. This is necessary so that the base color applied on top of it acquires a special shade.

Gray underpainting allows you to achieve an interesting optical effect. The most orthodox color palette includes only a few colors; the remaining colors are obtained by layering. To get a brown color, for example, you need to apply red paint to a gray base.

When the image is ready, the plaster is allowed to dry. This is the main way to create frescoes. In certain cases, they resorted to supplementing and clarifying the work already on a dry surface.

Icon "Archangel Michael"

Second half of the 14th century. Byzantine Museum, Athens

© National Gallery of Art

Large icon (110 × 80 cm), probably painted in Constantinople, depicts the Archangel Michael the Great Taxiarch (Officer) with a scepter and the sphere of the world, crowned with a cross, the initials Χ Δ Κ (“Christ the Righteous Judge”) and image of a lion. This image represents one of the perfect examples of the Palaiologan Renaissance. The basis of its content was the ancient model, which Byzantine artists never completely forgot, but at certain historical moments they turned to it as the leading one. The archangel's clothes are speckled with golden assist - a reflection of the same divine light that, according to Gregory Palamas, is communicated to man. The face of the archangel (interpreted very individually, almost portrait-style) is snatched from the shadows by an even and deep glow, spiritualizing and transforming matter. The image of the archangel emphasizes both his royalty (his attributes are the same as those of the autocrat who embodied the supreme power on earth) and his impressive monumentality.

First experiments

The history of mosaics begins during the Sumerian kingdom. The most ancient mosaics were assembled from pieces of baked clay. Unfired clay was used as a base.

The first mosaic was assembled from conical clay parts, the ends of which were painted. The colors commonly used were red, black and white. Mesopotamia, Uruk, 3 thousand years BC. e.

Simple geometric patterns were made from rosettes, triangles, and zigzags. In addition to decorative benefits, the mosaic here protects the supporting structure from moisture and weathering.