“Blessed is he who comes in the name of the Lord” (Matthew 21:9)

Holy Week begins with the remembrance of the Entry of the Lord into Jerusalem. Let's look at this event as the Evangelist Matthew describes it: “And when they drew near to Jerusalem and came to Bethany to the Mount of Olives, then Jesus sent two disciples, saying to them: go to the village that is right in front of you;

and immediately you will find a donkey tied and a colt with her; untie, bring him to Me; and if anyone says anything to you, answer that the Lord needs them; and he will send them forthwith. Nevertheless, this happened, so that it might be fulfilled which was spoken through the prophet, who says: “Say to the daughter of Zion: Behold, your king is coming to you, meek, sitting on a donkey and the colt of a donkey who has been yoked.”

The disciples went and did as Jesus commanded them: they brought a donkey and a colt and put their clothes on them, and He sat on top of them. Many people spread their clothes along the road, and others cut branches from trees and spread them along the road; The people preceding and accompanying exclaimed: Hosanna to the Son of David! Blessed is He who comes in the name of the Lord! Hosanna in the highest! And when he entered Jerusalem, the whole city began to stir, and they said: Who is this? And the people said: This is Jesus, the prophet of Nazareth of Galilee” (Matthew 21:1-11). Holy Week at Valaam Monastery

There is something mysterious in the Gospel, beyond linguistic description and logical definition. In fact, the One who reveals Himself here is the Eternal Son of God, before the creation of the world, abiding in the bosom of the Father. This means that from the very beginning He knows how His earthly journey will end. The Gospel texts repeatedly emphasize this consciousness of the Cross, the inevitability of which is revealed immediately after Peter's confession (Matt. 16:21). However, the Gospel is far removed from ancient fatalism, where the hero supposedly knows his fate. The category of fate itself cannot be applied to the life of Christ, for it is something external to the individual, causing his unfreedom. The Lord is absolutely free, His earthly path is rooted in this Divine freedom and, therefore, is the result of will, decision, and not abstract fate. But from the point of view of our human logic, this means that the Gospel and biblical events in general could have been different. And, indeed, freedom of choice means the potential for different developments of events. This is most clearly revealed in the Gethsemane prayer: “And he went away a little, fell on his face, prayed and said: My Father! if possible, let this cup pass from Me; however, not as I want, but as You"

(Matt. 25:39).

But this problem also extends to the people around Jesus. There is also a mysterious duality here. On the one hand, the ancient prophecies of the Old Testament in some way predetermine the course of events in the history of salvation: “Was it not necessary for Christ to suffer and enter into His glory? And beginning with Moses, he explained to them from among all the prophets what was spoken about Him in the Scriptures.”

(Luke 24:25-26).

On the other hand, they do not cancel human freedom and choice. The Savior Himself emphasizes this when speaking of Judas: “Nevertheless the Son of Man cometh, as it is written of Him;

but woe to that man by whom the Son of Man is betrayed: it would have been better for that man not to have been born” (Matthew 26:24). As we see, the Lord does not relieve the disciple who betrays Him of responsibility, which is possible only in the presence of freedom.

So, we have an obvious contradiction: biblical events appear to us as irreversible, on the one hand, but the doctrine of freedom expressed by Revelation suggests the possibility that these events could have been different, which means there is no predetermination. This is one of the main problems of theology, which the Church Fathers tried to solve. So, for example, St. Maximus the Confessor introduces here the concept of original sin: the irreversibility of the history of salvation is due precisely to the freedom of Adam’s tragic choice. Moreover, God’s love is such that the Incarnation would have taken place even in the absence of the fall of man, but then it would not have ended with Golgotha.

All these lines converge in the event of the Entry of the Lord into Jerusalem. There are only a few days left before the Cross, but now we see a jubilant people exclaiming: “Hosanna to the Son of David! Blessed is He who comes in the name of the Lord! Hosanna in the highest! For the first time, Jesus openly appears before Israel as the Christ: the Savior whom God's people have been waiting for for so many centuries. This moment of fulfillment of promises, the fullness of being, the divine power clearly felt here.

You can often hear the following interpretation of this Gospel passage: people who greet Christ so joyfully are inspired only because they see in him only an earthly political leader who will save them from Roman occupation and make Israel a powerful state again. And the moment the Lord reveals to them the true truth of God, they turn away from Him. Probably, this interpretation is indeed justified, but it is not the only one.

This moment can be understood as the action of the Spirit of God, which reveals to people the coming King of Glory. Here Heaven descends to earth so clearly and clearly that those “who preceded and accompanied” feel it with their whole being. There are no philosophical reflections or interpretations of Scripture; on the contrary, the scene is full of immediate childish joy about the Lord ascending to the Holy City. Such an enthusiastic acceptance of divine grace excludes all earthly logic. At the same time, those who doubt and do not trust Christ find themselves excluded from this universal joy: “When the high priests and scribes saw the miracles that He performed, and the children shouting in the temple and saying:

“Hosanna to the Son of David!”, they were indignant and said to Him : Do you hear what they say?

Jesus says to them: Yes! Have you never read: “From the mouths of babes and sucklings you have given praise”?” (Matt. 21:15-16).

So, during the entry into Jerusalem, the people, albeit for a short time, recognize in Jesus their Messiah-Christ. This good news is revealed by the Spirit of God, filling the hearts of people with great joy. In the same way, some time ago Peter saw God in His Teacher: “Simon Peter answered and said: You are the Christ, the Son of the Living God. Then Jesus answered and said to him, “Blessed are you, Simon son of Jonah, for it was not flesh and blood that revealed this to you, but My Father who is in heaven.”

(Matt. 16:16-17).

Here the question inevitably arises: how did the same people who saw the Savior in Jesus, after some time in the Sanhedrin begin to demand His execution? And here again the problem we posed above arises: the relationship between human freedom and divine providence.

During the Western Reformation, some theologians tried to resolve it by simply removing the concept of freedom from reasoning: man is a kind of instrument in the hands of God, which is used to save the elect. Such an understanding is deeply alien to Orthodoxy, which has always defended freedom as an integral part of personal existence. God does not break human will, but interacts, expecting a voluntary response from it: “Behold, I stand at the door and knock: if anyone hears My voice and opens the door, I will come in to him and will dine with him, and he with Me.”

(Rev. 3:20). Therefore, the event of the entry into Jerusalem should be understood in this light.

God reveals Himself to people, not as a political leader and an earthly king, but as mercy and love, meekly ascending to the Holy City, “sitting on the colt of a donkey, the son of the yoke.” He is not surrounded by a brilliant army; hosanna comes from the mouths of children. Nevertheless, the action of the Power of God is so powerful and visible that people cannot help but notice it. This is God's Gift to Israel, which can be accepted or rejected.

And further gospel events show that the moment of delight and joy quickly changes to disappointment. Human logic seems to push the Savior away when, in the temple, into the space of general rejoicing, doubt suddenly sneaks in: the high priests again demand evidence and signs. They did not believe Christ at the moment of the resurrection of Lazarus; on the contrary, it was after this that they began to directly develop a plan for His murder, and they did not believe it now. In just a few days, they will be able to poison the souls of people who are now sincerely rejoicing with this poisonous doubt. Therefore, in Matthew this chapter ends with the parable of the evil vinedressers.

Holy Week and the Colored Triodion

Thus, the event of the Entry of the Lord into Jerusalem is filled with an important theological meaning: this is the moment when the world was given the last chance to accept Christ. God's foreknowledge of His suffering does not mean the loss of freedom and responsibility for man. Moreover, this foreknowledge guarantees them. This is especially clearly noticeable in the scene of the arrest of the Savior: “And behold, one of those who were with Jesus, stretching out his hand, drew his sword and, striking the servant of the high priest, cut off his ear. Then Jesus said to him: Return your sword to its place, for all who take the sword will perish by the sword; or do you think that I cannot now pray to My Father, and He will present to Me more than twelve legions of Angels?”

(Matt. 26:51-52). It is precisely the fact that the Lord, knowing what awaits Him in Jerusalem, voluntarily renounces all “protection” and saves human freedom, even in its most disastrous and monstrous fall.

This is important for us to remember as we now enter the holy time of Holy Week. Remembering the Entry of the Lord into Jerusalem, we must remove destructive doubt from our hearts and, together with our children, sing hosanna to the Passion and Resurrection of Christ.

About the history of the holiday

The entry of the Lord into Jerusalem is one of the main events of the last days of the earthly life of Jesus Christ. His solemn arrival in the Holy City on the eve of Easter preceded His Passion and was the fulfillment of Old Testament prophecies. The people greeted the Savior as a king - with palm branches, spreading clothes under the hooves of a donkey. Therefore, the great twelve moving [1] feast of the Entry of the Lord into Jerusalem is also called the Week of Vaiya (branches) or Palm Sunday.

Ill.2. The entrance to Jerusalem (above) and the prophets who proclaimed it (below). Miniature of the Syriac Gospel of the 6th century. Duomo Museum in Rossano, Italy.

The beginning of the celebration apparently dates back to the second half of the 3rd century. From this time, the teaching on the Entry into Jerusalem by Bishop Methodius of Patara (313) [2] has been preserved. Saint Epiphanius of Cyprus (403) already speaks about the celebrations on this day [3]. The fact is that in Jerusalem on holidays “it was customary to hold mobile services with a tour of the shrines” [4]. Pilgrim of the 4th century Etheria (Sylvia of Aquitaine) in her Letters testifies to such a procession: “then everyone walks from the top of the Mount of Olives. And all the people go... with hymns and antiphons, constantly chanting: “Blessed is he who comes in the name of the Lord.” And all the children, how many of them there are in these places... are holding branches - some palm trees, others olive trees" [5]. IV-V centuries The teachings on the Entry into Jerusalem of many holy fathers date back, that is, the holiday became widespread in all local churches. In the VII-IX centuries. Saints Andrew of Crete, Cosmas of Maium, John of Damascus, Theodore and Joseph the Studites, as well as Emperor Leo the Philosopher and others composed hymns and canons for it, which became part of the liturgical tradition.

Interpretations of the Holy Fathers

At the same time, the symbolism of the Entry into Jerusalem is full of internal contradictions. On the one hand, Christ enters as a triumphant King, on the other hand, he rides in not on a horse, but on a young donkey, a symbol of meekness, and then voluntarily surrenders himself to the unrighteous court of the Sanhedrin, going to a shameful death on the cross. The entrance to the earthly city of Jerusalem became the beginning of the way of the cross and at the same time the beginning of the path to the Heavenly City. The day chosen by the Savior itself testifies to the atoning sacrifice. Saint Ambrose of Milan says that the Entry of the Lord Jesus Christ into Jerusalem took place on the tenth day of the month of Nisan (Ex. 12:3-6), when the Passover lamb was chosen, which was slaughtered on the fourteenth day (the first day of Passover). Consequently, Christ, as the true Lamb who was to suffer crucifixion on Friday, entered Jerusalem precisely when the representative lamb was being chosen [8].

Saint Epiphanius of Cyprus reflects on the complex symbolism of events in his word for the week Vaiy. “Why did Christ, having previously walked on foot, now and only now sit on an animal? In order to show that He will ascend to the Cross and be glorified on it. What does “opposite everything” mean? The obstinate disposition of the spirit of a man expelled from paradise, to whom Christ sent two disciples, that is, two Testaments, Old and New. Who does donkey mean? Without a doubt, a synagogue, which under a heavy burden carried life and on the back of which Christ will one day sit. Who does the foal mean? An unbridled pagan people, on whom no one sat, that is, neither law, nor fear, nor Angel, nor Prophet, nor Scripture, but only one God the Word” [9].

Mount of Olives, palm tree and Holy City

As iconography develops, complex compositions depicting solemn processions appear (Ill. 3). Such monuments were created primarily in the capital of the empire - Rome, where they sought to surround the Lord Jesus Christ with an aura of grandeur and splendor, including elements of triumphal themes in Christian iconography. Apparently, Rome was the place where this process took place most intensively. It received its continuation in Constantinople with its extensive court ceremonial. The composition of the Entry of the Lord into Jerusalem has something in common with the ancient triumphal processions of emperors [15].

Il. 6. Carved ivory plaque. Constantinople. X century Museum of Byzantine Art, Berlin.

By the middle of the 10th century, the iconography of the holiday had already been formed. An important element is the image of the Mount of Olives, which often serves as a background to highlight the central image, as on an ivory plaque of the 10th century. from the Berlin Museum (Fig. 6). In the mosaic of the Palatine Chapel in Palermo, Christ on a donkey and the apostles behind him are depicted descending from the mountain (Ill. 3). The artist directly followed the text of the Evangelist Luke: “And when He approached the descent from the Mount of Olives, the whole multitude of disciples began to praise God with great joy and loud voices for all the miracles that they saw” (Luke 19, 37) [16]. Saint Epiphanius of Cyprus gives his interpretation of this Gospel image: “What is the descent of Christ from the Mount of Olives? Without a doubt, nothing other than the descent from heaven to us of God the Word” [17].

Opposite the mountain, usually on the right, a city is depicted. The architecture of Jerusalem is represented by many quaint buildings behind a wall with towers. The Temple of Jerusalem is usually depicted in the center. From the 12th century In Byzantine and then Russian icon painting, a rotunda with a dome, topped with a cross, is depicted in the center of Jerusalem, reminiscent of the rotunda of the Resurrection in the Church of the Holy Sepulchre. Thus, earthly Jerusalem prefigures the Heavenly City and Temple, in which Christ eternally resides as God and High Priest [18].

An important place is given to the image of a palm tree and palm branches - fronds. In the Greek tradition, the holiday is called Κυριακή των Βαΐων (vai holiday), in Rus' - Flower Week or Palm Sunday. Palm tree is a symbol of victory, triumph, abundance. Notable persons were greeted with palm branches in their hands and were awarded to the winners. In Christian iconography, the palm tree becomes a symbol of martyrdom and victory over death. In the iconography of the Entrance to Jerusalem, the palm tree is a multi-valued symbol. Located between the mountain (a symbol of spiritual perfection) and Jerusalem (a symbol of the Heavenly City), it points to the heavenly and at the same time the Tree of the Cross, which the Savior will soon ascend.

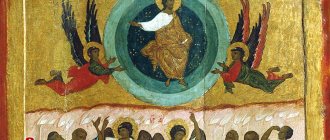

Il. 7. Andrey Rublev (?). Icon from the festive rite of the iconostasis. Annunciation Cathedral of the Moscow Kremlin. 1405-1410s(?)

In the Palaiologan era, new iconography appears. If earlier the Savior was depicted sitting on a donkey with his feet towards the viewer and facing the city, now He is most often presented in a complex perspective. Christ turns back to the apostles, His feet are not visible. This version became widespread in Russian art of the 15th century. (icons from the festive rows of the iconostasis of the St. Sophia Cathedral in Novgorod, ca. 1341; Annunciation Cathedral of the Moscow Kremlin, early 15th century (Ill. 7); Trinity Cathedral of the Trinity-Sergius Lavra, 1425–1427; Assumption Cathedral of the St. Kirill Belozersky Monastery, 1497) .

In icons of the 15th–16th centuries. There is one common feature that is consistent with liturgical texts. The Lord, moving in humility “to the city of Jerusalem to fulfill the scripture” (stichera on the stichera), is shown to be precisely the Meek King about whom Zechariah prophesied. Entering Jerusalem is an act of His good will. It will be followed by the atonement of human sins with the great sacrifice of the cross, which will open people's entrance to a new life - to the Heavenly City of Christ. The light of the general resurrection shines from the icons of the Lord entering Jerusalem for our salvation. [19].

Early iconography

With the beginning of the celebration of the Entry into Jerusalem, its first images appear. These are reliefs of Roman sarcophagi of the 4th century, which have a simple compositional scheme, but differ in details. Sometimes the Lord sits on a donkey (Il. 1), as it is said in the gospels of Mark, Luke and John, and sometimes on a donkey with a colt, as it is said, in confirmation of the prophecy of Zechariah (Zechariah 9, 9), by the Evangelist Matthew. It can be encountered by children breaking tree branches and spreading clothes, or by children and adults. He may be young and beardless or medieval [10].

In monuments of the V-VII centuries. We see new details that can be fixed in the iconography. On the carved plate of the frame of the Milanese Gospel of the 5th century. The Lord blesses those who spread clothes. On the plaque from the pulpit of Maximian (Ravenna, 545-556) He blesses with his right hand and holds a cross in his left; A woman spreads clothes before Him (Ill. 4). Perhaps this is the “daughter of Zion” - a symbolic image of Jerusalem. In the miniature of the red-backed Syriac Gospel of the 6th century, which is kept in the Rossano Cathedral (Ill. 2), you can see a very developed composition. The Lord, sitting on a donkey, is depicted almost frontally, with his feet towards the viewer, in a slight turn towards the inhabitants of Jerusalem, whom he blesses. They, in large numbers - children and adults - gathered at the city gates with palm branches. Two youths place blue and purple clothes under the donkey's hooves - in commemoration of the two natures of Christ. The Lord is accompanied by two disciples, a young one and a gray-haired one - these are the two He sent for the donkey. Nearby, two children climbed a tree and cut branches. This pairing of characters emphasizes the dual nature of the holiday, and also points to the two Testaments that formed the basis of the Church of Christ. A rare iconographic detail is people with palm branches greeting the King and Lord from the windows of a building outside the city wall.

Il. 5. Entrance to Jerusalem. Mosaic of the Church of the Assumption in the Daphne Monastery. Greece. XI century