The question of the end of the world and the afterlife has always interested people, which explains the presence of various myths and ideas, many of which are similar to fairy tales. To describe the main idea, eschatology is used, which is characteristic of many religions and different historical movements.

What is eschatology?

The religious doctrine of the ultimate destinies of the world and humanity is called eschatology. There are individual and global directions. Ancient Egypt played a big role in the formation of the first, and Judaism played a big role in the second. Individual eschatology is part of a universal trend. Although the Bible does not say anything about the future life, in many religious teachings the ideas of posthumous reward are perfectly read. Examples include the Egyptian and Tibetan Book of the Dead, as well as Dante's Divine Comedy.

ESCHATOLOGY

(from the Greek ἔσχατος - last, final) - in religious ideological systems, the doctrine of the final destinies of the human person and all things in “eternity”, i.e.

in the most definitive perspective, beyond the boundaries of history, biography, and “this” world in general. One must distinguish between individual eschatology, i.e. the doctrine of the posthumous fate of the individual human soul

, and universal eschatology, i.e. the teaching about the purpose and purpose of cosmic and human history, about their exhaustion of their meaning, about their end and what will follow this end. Individual eschatology is usually more or less significantly correlated with the universal, but the degree and modality of this correlation in different systems is very different; The degree of attention to eschatological issues as a whole is also varied, sometimes pushed to the periphery and reserved for closed mystery communities as a subject of instruction for the “initiated,” as in classical Greek paganism, sometimes coming to the very center of the doctrine offered to all, as in Christianity.

The idea that the “soul” or “spirit” of a person has some kind of existence after death, either passing through one incarnation after another, or dragging out a ghostly existence that is flawed even in comparison with this life in some locus like the Greek Hades or Jewish Sheol, is widespread among a variety of peoples, in a variety of civilizations and sociocultural contexts, right up to the paramythology of modern times (spiritism, ghost stories, etc.). But motives of this kind in themselves do not constitute a sufficient sign of individual eschatology. In mythological, religious and mystical teachings, more or less fundamentally oriented towards the cyclical paradigm of world processes (from the rituals of the agricultural cycle that set the tone for the myth to the quite consciously articulated Brahmanistic and Pythagorean-Stoic doctrines of the world year and eternal return), one can speak of eschatology in general only in in an improper sense, for the very idea of an eternal cycle excludes anything final; the universe has neither a meaningful goal nor an absolute end, and worldwide catastrophes that rhythmically destroy the cosmos only clear the way for what follows. The naturalistic-hylozoistic interpretation of the cosmos in myth and doctrine, readily presenting it as a biological organism, speaks of the replacement of the decrepit world body by a young one. This also includes the doctrine of a periodic universal fire, “which kindles in measure and goes out in measure” (Heraclitus, B 30). Since the central formula of archaic thought in its Greek philosophical articulation (for which it is not difficult to find analogues in other religions) says “one and all,” the rhythm of being is interpreted in myths and doctrines as a change of “exhalation,” i.e. the transition of the “one” into “all” as its otherness - “inhalation”, i.e. the return of “everything” to the self-existence of the “one”

: examples include the Neoplatonic triad “abiding” - “protruding” - “return”, Indian doctrines about the emergence of the world from the self-existent

atman

and the catastrophic return of the world to its original beginning, etc. Although pictures of world catastrophes are sometimes depicted in very vivid colors - an example is the “Divination of the Velva” in the Elder Edda, which depicts the death of the gods - we are not talking about the irreversible fulfillment of world meaning, but only about a change of cycles.

Individual eschatology also easily dissolves in the eternal cycle: for different types of pagan thought, ideas about the grave as the maternal womb of the Earth, the true mother of all children, are extremely characteristic, due to which death and burial appear identical to conception and returning the deceased back to earthly life; funeral rites readily embrace sexual symbolism. In the primitive stages of culture, there was a widespread belief that the deceased returns to earth in the body of a newborn from his family (for example, his grandson); then this faith is formalized into religious and philosophical doctrines about the transmigration of souls (for example, in Buddhism, among the Orphics, in Pythagoreanism, Kabbalism, etc.). These ancient motifs are reinterpreted in Schopenhauer’s teaching about the indestructible volitional core of our “I”, which produces new life after each death, in Nietzsche’s mythology of the eternal return, not to mention the themes of the occultism of New and Contemporary times. Under the sign of wandering from one incarnation to another, the boundaries between “I” and “not-I” are erased, which creates a situation of some kind of general incest. “He squeezes the breast that once nourished him, overcome with passion. In the womb that once gave birth to him, he indulges in pleasure. ...So in the cycle of being... a person wanders” (Upanishads. M., 1967, p. 228). This continuous cycle of migrations of the soul, which does not resolve into any final decision of its destinies (in Orphic terminology, the “wheel of birth”) can be perceived as unbearable hopelessness. This gives rise to the idea, fundamental to Buddhism, that the soul can break through the vicious circle of rebirths only by extinguishing itself (cf. Schopenhauer’s teaching on the conscious overcoming of the will to live). Only such an outcome can be final and absolute; Although Mahayana Buddhism develops ideas about heavenly and hellish spaces for souls, these decisions about the fate of the soul do not remove it from the power of the “law of karma.” nirvana can do the latter

, which turns out to be the only possible final, absolute deliverance.

Eschatology in its proper sense develops where a meaningful solution to personal and universal destinies becomes conceivable in a certain absolute perspective. A special role in the development of the influential tradition of individual eschatology belongs to ancient Egypt, and in the creation of the paradigm of universal eschatology - to ancient Israel and then Judaism.

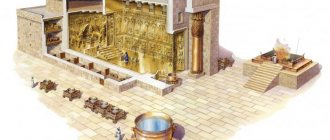

Ancient Egyptian thought, which worked hard on the problem of death and personal immortality, understood the afterlife as a positive existence, in its concrete fullness in no way inferior to earthly life, but unlike it, standing under the sign of final stability and therefore incomparably more important. Life in time should only serve as preparation for life in eternity. The irrevocable decision of the fate of the soul (“ka”, the incorporeal-corporeal double) is conceptualized in moral and religious terms as a trial of it before the throne of the afterlife god Osiris: a person must bring an account for his entire life, and his heart is weighed on the scales along with the “truth” as a standard. The condemned is devoured by a special monster (cf. the image of the “mouth of Hell” in the symbolic language of Christian eschatology), and the justified is forever installed in the resting places of the blessed, uniting and merging with Osiris (cf. the Christian formula “dormition in Christ”). The afterlife, with its impartiality, makes up for all the disharmonies of earthly life: “there is no difference between the poor and the rich.” In parallel with the moral emphasis on faith in a righteous court, interest develops in the possibilities of ensuring one’s destiny in the next world with the help of rituals or correct knowledge of what awaits the deceased, how to behave, how to answer questions, etc. (“books of the dead”, having parallels, for example, in the Tibetan tradition).

Biblical thinking takes a different path, focused not on the destinies of the individual, but on the destinies of the “people of God” and all humanity, on the religious understanding of world history as a process guided by the personal will of the one God. The historical catastrophes that befell the Jewish people (the so-called Babylonian captivity in 586 BC, the destruction of Jerusalem by the Romans in 70, the suppression of the Bar Kochba rebellion and the bloody repression of the Jewish faith under Hadrian) increase interest in eschatology; history pre-established from above must transcend itself in the coming of “a new heaven and a new earth” (Isaiah 65, 17), in the advent of the “future age” (this term, characteristic of Jewish apocalypticism, was included in the formula of the Christian Creed: “I tea... the life of the future century"). The individual eschatology articulated later fits completely into the context of universal eschatology, for the advent of the “future age” will be the time of the resurrection of the previously dead righteous, who will receive a “share in the future age.” Having absorbed the traditions of the understanding of history in Zoroastrianism that developed parallel to the biblical worldview, the post-biblical apocalypticism of the Qumran-Essene type interprets eschatological time as the final division between good and evil and the victory of the first over the second (cf. Amusin I.D.

Dead Sea Manuscripts. L., 1960, p. 117). As the solution to all disputes between men and spirits, the fulfillment of all the promises of God, and the fulfillment of the meaning of all things, eschatological time is referred to in Jewish religious literature simply as “the end”; the center of gravity moves decisively from the present to the future. The Lord and Finisher of the “end” will be God, but also his human-superhuman messenger and “anointed one” (msjh, in the Greekized Aramaic accent “Messiah”, in the Greek translation “Christ”); he will put an end to the times of “darkness”, gather the “people of God” scattered across the face of the earth, “make those who sleep in the earth flourish” (Pirge R., Eliezer 32, 61) and unite in himself the dignity of the king and the high priest. The tragic collapse of Jewish civilization in Spain after the so-called The reconquest and other catastrophes of European Jewry stimulated the actualization of the paradoxical teaching that the Messiah will come only after the extreme aggravation of disasters (the so-called “birth pangs of the coming of the Messiah”), so that the historical process should be treated according to the formula “the worse, the better” ; for example, in Hasidic legends, miracle workers (“tzaddikim”), who deliver people from troubles with their theurgic power, often receive the reproach that by doing this they are delaying the coming of the Messiah.

Christian eschatology grew on the basis of a biblical-messianic, dynamic understanding of sacred history moving towards the end, which turned out to be derived from the ethnopolitical context of the “people of God according to the flesh” to the horizons of “universal”, pan-human, and enriched with motives of Hellenistic intercultural synthesis (characteristic of the significance of prophecies for early Christianity about world renewal in such Greek and Latin texts as the so-called Sibylline Book or Virgil’s 4th Eclogue). The starting point of the new faith was the conviction of the first Christian “evangelists”, according to which the eschatological accomplishment had already essentially begun, since Jesus Christ (i.e. the Messiah) came in the “last times” (1st Apostle Peter, 1, 20) and “he has overcome the world” (Gospel of John, 16, 33). However, the image of the eschaton was doubled from the very beginning. Christ came for the first time “in the form of a servant” to teach, heal and redeem with his sufferings, and not judge people (Gospel of Matt. 18:11); the second coming of Christ will be “with glory,” for the final judgment of the living and the dead (cf. the text of the Nicene-Constantinople Creed). In the first coming, history was overcome only invisibly, for the faith of believers, empirically continuing to move on, although already under the sign of the end. At the end of the Apocalypse, the last and most eschatological book of the New Testament canon, it is said: “Let the unrighteous still do injustice; let the unclean one still become unclean; let the righteous still do righteousness, and let the holy one still be sanctified. Behold, I come quickly, and My reward is with Me...” (Rev. John 22:11-12). Only the second coming will reveal the hidden reality of the first, but it should come unexpectedly, at a time about which believers are forbidden to guess and speculate, catching people in the routine of their everyday behavior (an incentive to bring severity to themselves precisely in this routine). Because of this, the imperative of eschatology is noticeably interiorized, as if transferred to the spiritual world of man and his religiously motivated relationships with other people (“The Kingdom of God is within you.” - Luke 17, 21 - words that in the Greek original and taking into account the Semitic lexical the substrate can also be understood “between you”, in the righteousness of your interpersonal communication); however, through the doctrine of the second coming, the significance of universal, worldwide eschatology is also preserved. At the same time, the first and second comings of Christ express the polar relationship between two properties of God - mercy and judging justice (cf. the symbolism of the right and left hands, for example, in the Gospel of Matthew 25, 33 ff.).

This complex eschatology of the New Testament could express itself only in polysemantic parables and symbols, avoiding excessive visualization. However, medieval Christianity, in countless apocrypha, legends and visions, creates a detailed picture of the other world (cf. the Byzantine apocrypha “The Virgin Mary’s Walk through the Torment”, very popular in Rus'). At the level of sensory-presentable myth, the topic of eschatology often turns out to be de facto interreligious (for example, Islamic ideas indirectly influence the imagery of Dante’s “Divine Comedy”, the houris of the Islamic paradise are similar to the apsaras of Buddhism, etc.); Currents of folk myth-making cross all religious and ethnic boundaries. In Christianity, there is a reception of motifs of individual eschatology of Egyptian and Greco-Roman origin (for example, the motif of Osiris weighing the heart of the deceased was reworked into the motif of the same weighing in the face of the Archangel Michael). Similar processes are noticeable in the more mental area, where the ancient concept of “immortality of the soul” crowds out the concept of “resurrection of the dead” articulated in the Christian Creed. The more acute the problem of reconciling such motives with biblical and early Christian all-human eschatology becomes. If the fate of each individual soul is decided by its weighing on the scales of Michael and its placement in heaven or hell, the place of the motive of the general resurrection and judgment of humanity in the context of the end of the world is unclear. The most common solution to this problem (known from the Divine Comedy, but which arose much earlier) proceeded from the fact that the joys of heaven and the torments of hell are experienced by souls separated from their bodies only in anticipation of receiving their definitive fullness after the bodily resurrection and the Last Judgment . By this, individual eschatology no longer combined not two, but three logically distinguishable points: if the righteous 1) already in earthly life, through his spiritual meeting with Christ who revealed Himself, secretly has an eschatological “new life”, and 2) after death receives “eternal life” in paradise ", then both of these events are fully realized only in 3) the final event of the resurrection and enlightenment of his flesh at the end of the world.

The latter was often interpreted by mysticism as the restoration of the entire created universe to its original perfection: man as a microcosm and a mediator between nature and God (see: Thunberg L.

Microcosm and Mediator: The Theological Anthropology of Maximus the Confessor.

Lund, 1965) overcomes its split into two sexes (an ancient motif known from Plato’s “Symposium”), then overcomes the split of the world into earthly and angelic being, transforming earth into paradise, then reconciles the sensual and intelligible in its essence and completes its mediation service in that, having reunited all levels of existence within himself, through love he gives them to God and thereby fulfills their purpose. Ideas about the transfiguration and thereby the “deification” of the flesh are especially characteristic of Orthodox mysticism (Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite, Maximus the Confessor, hesychasts); in the West they are most clearly represented in the eschatology of John Scotus Eriugena, which is atypical for the Western context (see Brilliantov A. The influence of Eastern theology on Western in the works of John Scotus Eriugena. St. Petersburg, 1898, pp. 407–414). Already Origen had the idea of the so-called. “apokatastasis” (Greek “restoration”, here - comprehensive enlightenment and return to the primordial good state) was brought to extreme conclusions about the necessary final salvation of all personal beings, including Satan, and, consequently, about the temporary nature of the torments of hell, which only last for purifying - pedagogical, but not actually punitive purpose. This extreme eschatological optimism (quite popular in today's theology, especially Western, in the context of the struggle against "repressive" tendencies of thought) is not easy to reconcile with both the Christian belief in the final nature of eschatological judgments and with the theistic belief in free will

(for in order to to postulate the inevitable salvation of the soul, one has to deny it freedom, arbitrarily reject the mercy of God and thereby perpetuate one’s condemnation).

Therefore, Origen's doctrine of apocatastasis was recognized as heretical at the 5th Ecumenical Council in 553, although it continued to find echoes in the history of Christian thought from Gregory of Nyssa and Eriugena to the theologians of modern times. However, the very idea of the place of temporary purgative torment (characteristic, by the way, of Greco-Roman eschatology, cf. the 6th book of Virgil’s Aeneid) was retained in Catholic theology in the form of the concept of purgatory and, along with the doctrine of the eternity of torment in hell as another otherworldly locus. The dogma of purgatory in its Catholic development was rejected by the Orthodox doctrine, which, however, also speaks of the so-called. "ordeals", i.e. temporary torments, trials and wanderings of the soul separated from the body. Meanwhile, the practice of prayers “for the repose of the souls” of the dead, equally important for Orthodoxy and Catholicism, itself suggests the possibility of some temporary afterlife states that have not yet been terminated by a definitive sentence immediately after death; radical trends of Protestantism, rejecting the idea of “purgatory” or “ordeals,” quite logically also abolished prayers for the dead. Orthodox eschatology, having many common premises with Catholic eschatology, is generally comparatively less dogmatically fixed and expresses itself to a greater extent in the language of polysemantic symbolism (liturgical texts and chants, iconography), which allows some Orthodox theologians to leave the door ajar for the doctrine of apocatastasis (Fr. P. Florensky, Father S. Bulgakov, etc.), resorting to deliberately “antinomic” formulations: “If... you ask me: “Well, will there be eternal torment?”, then I will say: “Yes.” But if you still ask me: “Will there be a universal restoration in bliss?”, then again I will say: “Yes”” ( Florensky P.A.

The Pillar and the Statement of Truth. M., 1990, p. 255).

In the doctrines and “heresies” of European Christianity at the end of the Middle Ages and on the threshold of the New Age, there was a noticeable transfer of interest from individual eschatology to universal eschatology. Here we should note first of all the doctrine of the coming after the successive eras of the Father (Old Testament) and the Son (New Testament) of the third era of the Holy Spirit, developed by Joachim of Flora (d. 1202) and which found supporters for centuries until the mystics of the 20th century. (in particular, Russian symbolists). Unrest of an eschatological nature is easily combined with anguish of disappointment in the idea of theocracy, as can be seen in the example of the Russian Old Believers: if the Russian kingdom ceases to be perceived as an “icon” of the Kingdom of God, it is easily identified as the kingdom of the Antichrist. One can note the role of secularized “chiliasm” (i.e., going back to the mysterious place of the Apocalypse [20, 2–7], not accepted by church teaching, but an influential eschatological doctrine about the coming thousand-year kingdom of the righteous) in the formation of a number of ideologies of the New and modern times - Puritan Americanism, utopian and Marxist communism (cf. recognition and analysis of this connection of ideas from a Marxist point of view in the acclaimed book: Bloch E.

Das Prinzip Hoffnung, Bd.

1–3. V., 1954–59), the Nazi mythology of the “thousand-year” Third Reich (in German the same word as the biblical “kingdom”), etc. Eschatology as “metahistory”, i.e. self-transcendence of the noticeably accelerating course of history is one of the leading themes of religious thought of the 20th century, undergoing not only all kinds of non-religious processing of a utopian or, on the contrary, “dystopian” and “alarmist” character, but, especially at the end of the century, everyday vulgarization, including n. totalitarian sects, as well as in completely secular media and the most trivial forms of art: “apocalypse” is today a hackneyed newspaper metaphor, and “Armageddon” is a normal motif in a horror film. Issues of individual eschatology are subject to the same vulgarization (cf. for the 19th century, spiritualism, for the 20th century, bestsellers about “life after death” like R. Moody’s book “Life after Life,” 1975, etc.). The eudaimonism of the “consumer society” has long given rise to a relaxed attitude towards eschatology and forms of trivialized discourse, for which “the next world” is a continuation of emotional comfort “here” (cf. Kagramanov Yu.

“...And I will repay.” About the fear of God in the past and present .– “Continent”, No. 84, pp. 376–396). In the field of professional theology, on the contrary, recently there has been a decline in interest in the topics of eschatology, which is increasingly becoming a specialty of fundamentalist and generally more or less “marginal” religious groups and individuals. The situation of serious eschatology, which finds itself in a threatening space between aggression from both secularism and the sectarian spirit, is a problem for today’s religious thinker, whatever his confessional (or non-confessional) affiliation.

Literature:

- Sakharov V.

Eschatological works and legends in ancient Russian writing and their influence on folk spiritual poetry. Tula, 1879; - Kulakovsky Yu.A.

Death and immortality in the ideas of the ancient Greeks. K., 1899; - Davydenko V.F.

Patristic idea of the human soul. Kharkov, 1909; - Zelinsky Φ.Φ.

First light show.

– In the book: He is the same.

From the life of ideas, 3rd ed., vol. 1. Pg., 1916, p. 185–236; - It's him.

Homer – Virgil – Dante. – Ibid., vol. 4, no. 1. Pg., 1922, p. 58–79; - Mashkin N.A.

Eschatology and messianism in the last period of the Roman Republic. – “Izvestia of the USSR Academy of Sciences”, series of history and philosophy, 1946, vol. 3, no. 5; - Vasiliev AA

Medieval Ideas of the End of the World: West and East. – “Byzantion”, 1944, XVI, p. 462–502; - Florovsicy G.

The Patristic Age and Eschatology: An Introduction. – “Stadia Patristica”, II. V., 1956, S. 235–250; - Bultmann R.

History and Eschatology. Edinburgh, 1957; - Ladd GE

Jesus and the Kingdom. The Eschatology of Biblical Realism. NY, 1964.

S.S. Averintsev

Eschatology in philosophy

The presented teaching not only talks about the end of the world and life, but also about the future, which is possible after the disappearance of imperfect existence. Eschatology in philosophy is an important movement that considers the end of history, as the completion of a person’s unsuccessful experience or illusions. The collapse of the world simultaneously implies the entry of a person into an area that combines the spiritual, earthly and divine parts. The philosophy of history cannot be separated from eschatological motives.

The eschatological concept of the development of society has become widespread in the philosophy of Europe to a greater extent thanks to the special European thinking, which considers everything that exists in the world by analogy with human activity, that is, everything is in motion, has a beginning, development and end, after which the result can be assessed . The main problems of philosophy that are solved with the help of eschatology include: understanding history, the essence of man and methods of improvement, freedom and opportunity, as well as various ethical problems.

Eschatology in Christianity

When compared with other religious movements, Christians, like Jews, refute the assumption that time is cyclical and claim that there will be no future after the end of the world. Orthodox eschatology has a direct connection with chiliasm (the doctrine of the coming thousand-year reign of the Lord and the righteous on earth) and messianism (the doctrine of the future coming of God's messenger). All believers are confident that soon the Messiah will come to earth for the second time and the end of the world will come.

At its inception, Christianity developed as an eschatological religion. In the letters of the apostles and in the book of Revelation one can read the idea that the end of the world cannot be avoided, but when it will happen is known only to the Lord. Christian eschatology (the doctrine of the end of the world) includes dispensationalism (ideas that view the historical process as a sequential distribution of divine Revelation) and the doctrine of the rapture of the church.

Eschatological ideas in the pagan world

Ideas about the afterlife - languor in the underground kingdom of the dead, torment, wanderings in a ghostly world or peace and bliss in the land of gods and heroes - are widespread, and this is clear evidence that these ideas did not arise from human imagination, but originate from the Divine revelations. Although they apparently have deep psychological roots, this can also be considered as evidence that the soul remembers its immortality.

As religion penetrates with moral ideas, ideas about afterlife judgment and retribution also appear, although religion seeks to provide the believer with afterlife bliss in addition to his moral merits - through spells or other religious means, as we see among the Egyptians, and later among the Greeks or Gnostics.

Along with the question of the fate of an individual human personality, a question may also arise about the final fate of all humanity and the whole world - about the “end of the world”, for example among the ancient Germans (twilight of the gods), or in Parsism (although it is difficult to determine the time of the emergence of its eschatology).

Eschatology in Islam

In this religion, eschatological prophecies concerning the end of the world are of great importance. It is worth noting that discussions on this topic are contradictory, and sometimes even incomprehensible and ambiguous. Muslim eschatology is based on the injunctions of the Koran, and the picture of the end of the world looks something like this:

- Before the great event occurs, there will come an era of terrible wickedness and unbelief. People will betray all the values of Islam and they will wallow in sins.

- After this, the reign of the Antichrist will come, and it will last 40 days. When this period ends, the Messiah will come and the Fall will end. As a result, within 40 years there will be an idyll on earth.

- At the next stage, a signal will be given about the onset of the Last Judgment, which will be carried out by Allah himself. He will interrogate everyone, both living and dead. Sinners will go to Hell, and the righteous will go to Paradise, but for this they will have to cross a bridge through which they can be transferred by animals that they sacrificed to Allah during their lifetime.

- It is worth noting that Christian eschatology was the basis for Islam, but there are also some significant additions, for example, it is indicated that the Prophet Muhammad will be present at the Last Judgment, who will be able to mitigate the fate of sinners and will pray to Allah to forgive their sins.

The meaning of the word Eschatology according to the Brockhaus and Efron dictionary:

Eschatology - the doctrine of last things, about the ultimate fate of the world and man - has occupied religious thought from time immemorial. Ideas about the afterlife - languishing in the underground kingdom of the dead, torment, wandering in a ghostly world, or peace and bliss in the land of gods and heroes - are widespread and apparently have deep psychological roots. As religion penetrates with moral ideas, ideas about afterlife judgment and retribution also appear, although religion seeks to provide the believer with afterlife bliss in addition to his moral merits - through spells or other religious means, as we see among the Egyptians, and later among the Greeks or Gnostics. Along with the question about the fate of an individual human personality, the question may also arise about the final fate of all humanity and the whole world - about the “end of the world,” for example, among the ancient Germans (twilight of the gods), or in Parsism (although it is difficult to determine the time of the emergence of its eschatology), or finally, among Jews, Muslims and Christianity. Among the Old Testament Jews, individual E., i.e., the set of ideas about the afterlife existence of an individual, is displaced from the area of religious interest proper, which focuses on national or universal E., i.e., on ideas about the final fate of Israel, the people of God, and therefore, the works of God on earth. In popular beliefs, such an end, naturally, was the exaltation of Israel and its national kingdom as the kingdom of Yahweh himself, the God of Israel, and His Anointed One or Son - the people of Israel, personified in the king, prophets, leaders, and priests. The prophets invested the highest spiritual content into the idea of the kingdom of God. This kingdom cannot have exclusively national significance: its implementation - the final realization of God's holy will on earth - has universal significance for the whole world, for all peoples. It is defined primarily negatively

, as judgment and condemnation, exposure and overthrow of all godless pagan kingdoms and at the same time all human untruth and lawlessness.

This judgment, in its universality, concerns not only the pagans, the enemies of Israel: it begins with the house of Israel, and, from this point of view, all historical catastrophes that befall the people of God seem to be signs of the judgment of God, which is justified by the very faith of Israel, is divine- necessary. On the other hand, the ultimate realization of the kingdom is defined positively

as

salvation

and

life

, as renewal, concerning the spiritual nature of man and the outer nature itself.

During the Babylonian captivity and after it, the religion of the Jews received a particularly deep and rich development, along with messianic aspirations.

From the 2nd century

in apocalyptic literature it is combined with beliefs and ideas about personal immortality and afterlife retribution. The various monuments of this period are distinguished by their variety of representations. we can talk about apocalyptic legends

, and not about apocalyptic tradition.

Some monuments speak of a personal Messiah, of the resurrection of the dead, of a prophet of the last times. others are silent about it. Nevertheless, gradually, right up to Christian times (and subsequently), a certain set of apocalyptic ideas was developed, which were included in Christian Elements. Studying systematically, starting from the 2nd century. BC, the ideas of the Jews about the “last things”, one can generally accept the following scheme: 1) tribulations and executions, disasters and signs of the last times, the visible triumph of the pagans, the wicked and lawless, the extreme tension of evil and untruth preceding the “end "(certainly a common feature of all apocalypses). 2) in wide circles there is a widespread expectation of the prophet, the forerunner of the great “day of the Lord,” Elijah (Malachi. Deuteronomy, 18, 15. Matt., 16, 14. John, 6, 14). 3) the appearance of the Messiah himself (not in all monuments), the last struggle of the enemy forces against the kingdom of God and the victory over them by the right hand of the Messiah or God himself. At the head of the enemy forces is sometimes placed the ungodly king (later the Antichrist) or Belial himself. 4) judgment and salvation, the renewal of Jerusalem, the miraculous gathering of the scattered sons of Israel and the beginning of the blessed kingdom in Palestine, which will last 1000 (sometimes 400) years - the so-called chiliasm

(see).

before the beginning of this “millennial kingdom” the righteous are resurrected in order to take part in its bliss (in some apocalypses the Messiah dies, and the last episode of God’s struggle with the enemy’s power is played out). 5) after the end of history, after the passing of time, some talk about the end of the world - the renewal of the universe. The “last trumpet” heralds the general resurrection and general judgment, followed by the eternal bliss of the righteous and the eternal torment of the condemned. Others imagined eternity itself by analogy with time and dreamed of a universal Jewish kingdom, with its capital in Jerusalem. Others thought of the coming kingdom of glory as a complete renewal of heaven and earth, as the realization of the divine order, the abolition of evil and death, preceded by the fiery baptism of the universe. Connected with this is the idea of a double resurrection

: the first resurrection of the righteous, at the beginning of the thousand-year kingdom - the seventh millennium, the seventh cosmic day, the Sabbath of the Lord, with which

history

.

the second judgment and the second general

resurrection are the end, the goal

of the cosmic

process.

A study of the Christian

apocalypse shows how these ideas of Jewish apocalypse were adopted and reworked by the first century church.

The “Gospel of the Kingdom” is directly adjacent to the preaching of John the Baptist, in whom they saw Elijah, the forerunner of the day of the Lord. “Repent, for the kingdom of heaven is at hand” - this is what John taught, and this is what the apostles taught during the life of Jesus. In both sermons, the kingdom of God, as the perfect

implementation of God’s will on earth (“as in heaven”), is recognized primarily as

judgment

, but at the same time as salvation.

It approached, it came, although without any visible catastrophe. it is already among people, in the person of Jesus, who recognizes himself as the only begotten Son of God, anointed by the Spirit, and is called the “Son of Man” (as in Daniel or in the book of Enoch), i.e. the Messiah, Christ. The Messiah contains the kingdom within himself, is its focus, bearer, sower. In it the New Testament is realized - the internal, perfect union of the divine with the human, the guarantee of which is that unique in history intimate, direct union of personal self-consciousness with God-consciousness, which we find in Jesus Christ and only in Him. The inner spiritual side of the kingdom of God in humanity finds its full realization here: in this sense, the kingdom of God has come

, although it has not yet appeared in the fullness of its glory.

Jesus Christ is “the judgment of this world” - that world that “did not know” and did not accept Him. and together He is “salvation” and “life” for those who “know”, accept Him and “do the will of the Father” revealed in Him, that is, become a “son of the kingdom.” This internal union with God in Christ, this spiritual creation of the kingdom of God does not, however, abolish faith in the final realization of this kingdom, its “appearance” or coming “in power and glory.” The last word of Jesus to the Sanhedrin, the word for which He was condemned to death, was a solemn testimony of this faith: “I am (the son of the Blessed One), and you will see the Son of Man sitting at the right hand of the Power and coming with the clouds of heaven” (Mark 14: 62). Conscious of Himself as the focus of the “kingdom,” Jesus could not help but feel its immediate proximity

(Mark 13:21 et seq.), although He recognized the date of its coming as known to the Father alone (ib., cf. Acts 1:7).

but the consciousness of the immediate proximity of the kingdom, or the “messianic self-consciousness” of Christ had for Him the practical consequence of the conscious necessity of suffering and death - for the redemption of many, for saving them from judgment and rejection associated with the immediate onset of the kingdom from which they, in their internal attitude, to him, they exclude themselves. The Father's commandment is not to judge, but to save the world. Not the appearance in glory among legions of angels, but death on the cross - this is the path to inner victory over the world and man. And yet, this death on the cross also does not abolish the Eternal kingdom: it only gives it a new meaning. The first generation of Christians was completely imbued with the idea of the nearness of the kingdom: you will not have time to go around the cities of Israel before the Son of Man comes (Matt. 10:23). This generation (generation, γενέα.) will not pass away until all these things happen (Mark 13:30). Christ's beloved disciple will not die before the coming of the kingdom. The fall of Jerusalem is a sign of the imminent coming (Mark 13, 24. Luke 21, 27), and if during the siege and storming of Jerusalem the Jews were every minute expecting the glorious and miraculous appearance of the Messiah, then among Christians of the first century these expectations are felt with no less force , being a consolation in sorrow and persecution and at the same time an expression of living faith in the immediate proximity of Christ. The last times are approaching (James 5:8; 1 Pet. 4:7; 1 John 2:18); the Lord will come soon

(Rev. 22:9 et seq.).

salvation is closer than at the beginning of the sermon, the night passes and dawn comes (Rom. 13, 11, 12). The Resurrection of Christ, as the first victory over death, served as a guarantee of the final victory, the general resurrection, the liberation of all creation from slavery to corruption. “manifestations of the Spirit” serve as a guarantee of the final triumph of the Spirit, the spiritualization of the universe. “The hope of the future and the resurrection of the dead” - this is how the Apostle Paul sums up his confession and doctrine (Acts 23:6). Within the framework of traditional E. (Antichrist, the gathering of Israel, judgment, resurrection, the reign of the Messiah, paradise, etc.), the apostle puts the basic Christian thought: in the resurrection and glorious realization of the kingdom, the final union of God with man is accomplished, and through him with all by nature, which is completely transformed and freed from corruption. God will be all in all (1 Cor. 15). From the end of the 1st century. perplexities arise, as evidenced by the monuments of the post-apostolic age, for example the epistle of Clement, and the later writings of the New Testament, such as the epistle to the Hebrews or the second epistle of Peter. The first Christians and apostles died without waiting for “salvation.” Jerusalem is destroyed. pagan Rome continues to reign - and this is in doubt. Scoffers appear who ask, where are the promises about the coming of Christ? Since the fathers died, everything remains the same as it was from the beginning of creation. In response to these ridicule, the second letter of Peter points out that just as the former world was once destroyed by the flood, so the present heaven and earth are reserved for fire, reserved for the day of judgment and destruction of the wicked. One thing you need to know is that “with the Lord one day is like a thousand years, and a thousand years like one day” (Ps. 90:4) - why the delay in the fulfillment of the promise should not be explained by slowness, but by long-suffering (chap. 3) . This text, in connection with the legend of chiliasm, has given rise to numerous interpretations. by the way, it caused anticipation of the end of the world around the year 1000, and then in the 14th century, since the “millennial kingdom” began to be considered to have come from the time of Constantine. E. in general is perhaps one of the first dogmas of Christianity. the first century was its heyday. Subsequent centuries lived on the traditions of early Christian and partly Jewish E., and over time, some ancient traditions fell away (for example, the sensual idea of chiliasm, which played a significant role in Jewish apocalypticism and was borrowed by Christians of the first centuries: see, for example, fragments of Papias) . Among the later appendages, we note the idea of ordeals, which once played an important role among the Gnostics, but was also adopted by the Orthodox. The history of the Western Church has been enriched by the doctrine of purgatory. Medieval dogmatics scholastically developed all particular questions about “last things.” in the “Summa Theologiae” of Thomas Aquinas one can find detailed information about the various parts of the afterlife, about the location of forefathers, children who died before baptism, about the womb of Abraham, about the fate of the soul after death, about the fire of purgatory, about the resurrection of bodies, etc. Fiction We find the expression of these views in Dante’s “Divine Comedy”, and in our country - in apocryphal literature about heaven and hell, walks through torment, etc., which lasts for many centuries and the beginnings of which should be sought in the early apocryphal apocalypses. Modern thought treats E. indifferently or negatively. those preachers of Christianity who strive to adapt it to the requirements of modern thought in order to open it wide access to the circle of the intelligentsia, often quite sincerely try to present Christianity as an accidental appendage of Christianity, as a temporary and transitory moment, as something brought into it from the outside by that historical environment , in which it arose. Already for the Greek intelligentsia, E. of the Apostle Paul served as a temptation, as we see from the impression made by his speech before the Areopagus: “when they heard about the resurrection of the dead, they began to mock, and others said: we will listen to you about this at another time” ( Acts 17, 32, cf. 24, 25). Nevertheless, even now every conscientious historian who scientifically studies the history of Christianity is forced to admit that Christianity as such, that is, as faith in Christ, the Messiah

Jesus, was necessarily from the beginning associated with E., which was not an accidental appendage, but an essential element of the gospel of the kingdom.

Without renouncing itself, Christianity cannot renounce faith in God-manhood and in the kingdom of God, in the final, perfect victory, the realization of God on earth - the belief expressed by the Apostle in 1 Corinthians (15, 13 et seq.). Individual images of Christian Elements can be explained historically, but its main idea, testified by the life and death of Christ

Jesus and the entire New Testament, starting with the Lord’s Prayer, still represents the vital question of Christianity - faith “in One God, the Father Almighty.”

Is there a world process, beginningless, endless, aimless and meaningless, a purely spontaneous process, or does it have a rational final goal, an absolute (i.e., in religious language, divine) end? Does such a goal or absolute good exist (i.e. God) and is this good realizable “ in everything

” (the kingdom of heaven - God is all in all) or does nature represent

the eternal

limit for its implementation and it itself is only a subjective, illusory ideal ?

Christianity has only one answer to this. Book S.T.

Eschatology in Judaism

Unlike other religions, in Judaism there is a paradox of Creation, which implies the creation of a “perfect” world and man, and then they go through a stage of fall, reaching the brink of extinction, but this is not the end, because by the will of the creator, they again come to perfection. The eschatology of Judaism is based on the fact that evil will end and good will ultimately win. The book of Amos states that the world will exist for 6 thousand years, and the destruction will last 1 thousand years. Humanity and its history can be divided into three stages: the period of desolation, the teaching and the era of the Messiah.

Is the doctrine of the ultimate destinies of the world and man firmly established?

The Church has not established a single generally binding dogmatic definition in the field of eschatology, writes Archpriest. Sergius Bulgakov, except for the brief testimony of the Nicene-Constantinople symbol about the second coming: “I hope for the Resurrection of the dead and the life of the next century” (meanwhile, the Church does not reject the divinely revealed doctrinal authority for many private truths of an eschatological nature noted in the Holy Scriptures). In this member of the Creed, the verb “to expect” (προσδοκώ) is found simultaneously and in full accordance with the verb “to believe” (πιστεύω). “To expect” means to firmly believe, to expect something as something completely definite, not subject to any doubt. There is a certain difference between the concepts of aspiration and hope. Aspiration means waiting with confidence, while hope can, however, be only a psychological expectation of the unattainable. Therefore, Christian hope is firmly tied to Christian aspirations.

Scandinavian eschatology

Scandinavian mythology differs from others in its eschatological aspects, according to which everyone has a destiny and the gods are not immortal. The concept of the development of civilization implies the passage of all stages: birth, development, extinction and death. As a result, a new one will emerge from the ruins of the past world and a world order will be formed from chaos. Many eschatological myths are built on this concept, and they differ from others in that the gods are not observers, but participants in events.