Iconoclasm, or iconoclasm, is a movement that appeared in different countries and entered world history. Its essence was to promote the destruction of images, sculptures, and other works of art associated with religion. During the existence of Christianity, iconoclastic sentiments periodically flared up in various territories, but they manifested themselves most actively in Byzantium. Opponents of religious paraphernalia used a variety of methods to combat their opponents, including the most cruel - torture, execution, and repression.

Early iconoclastic sentiments

Criticism of church symbols that have a superficial resemblance to ordinary people took place back in Ancient Rome and Ancient Greece. The ancient Greek philosopher Heraclitus condemned the materiality of sculptural compositions. The founder of the Eleatic school, Xenophanes, considered the idea of creating artwork in which the inhabitants of heaven looked like mortals to be ridiculous.

In the 2nd century, the attitude of Christians towards religious images became increasingly controversial. The doubts were based on the text of the second commandment given from above to the prophet Moses, calling not to create idols. During this period, cases of vandalism began to be recorded - the beheading of sacred statues, deprivation of their eyes, and complete destruction. In Persia, the iconoclastic heresy manifested itself in the deliberate extinguishing of ritual fires.

In the 4th century, objections to the worship of holy images and the core ideas of the iconoclasts began to intensify. The Roman theologian Eusebius of Caesarea criticized the desire of believers to pray at icons depicting Christ. The saint from Palestine Epiphanius of Cyprus committed an act unheard of in those times - he openly destroyed the Divine face in the Christian church.

The fight against icons in Byzantium

In Byzantium, the movement intensified in the 8th century, which is considered as the beginning of the era of iconoclasm. Historians identify the following reasons for this phenomenon:

- excessive worship of believers before icons, humanization of holy images;

- the perception of religious paintings as idols, which meant a return to paganism;

- the desire of the rulers of Byzantium to weaken the authority of the Church, reduce the role of the clergy in the political life of the state, and take away part of the church wealth.

The first period of iconoclasm lasted from 730 to 787. under the leadership of Emperor Leo III the Isaurian. The policy of this ruler was continued by his son Constantine V and grandson Leo IV. Supporters of the iconoclastic movement fiercely fought against the tradition of worshiping sacred images. Many icon venerators were persecuted, severely tortured, and ended up in prison. Only under Empress Irina was the Seventh Ecumenical Council held, after which the persecution temporarily ceased, and the worship of icons in the Christian Church was officially restored.

The second stage of iconoclasm, which took place from 814 to 842, was accompanied by increased repression against admirers of sacred images. The iconoclast emperor Theophilus, who ruled in Byzantium from 829 to 842 and imprisoned a large number of clergy, distinguished himself with particular cruelty. Only after the death of this ruler, his God-fearing wife Theodora was able to completely revive the long-standing tradition of icon veneration.

The final victory of the icon-worshipers took place in 842 after the Council of Constantinople. The veneration of holy images was recognized by all representatives of the Christian world, and the iconoclasts were anathematized.

Icon veneration. The most ancient icons. Iconoclasm and its Ecumenical Councils

| The book “Returning to the Origins of Christian Doctrine” | |

| Next >> | |

| Chapter: | |

In the Wikipedia encyclopedia (www.wikipedia.org) you can read about the history of icon painting:

«Ancient

Of the icons that have come down to us, they date back to

the 6th century

and were made using the encaustic technique (painting in which the binder of paint is wax. – Author’s note) on a wooden base, which makes them similar to Egyptian-Hellenistic art (the so-called “Fayum portraits” )".

Some theologians confirm that the early church did not know icons, and catacomb painting was only symbolic. Here is how Doctor of Theology, historian of the Orthodox Church, Archpriest Alexander Schmeman (1921 - 1983) wrote about this in his book “The Historical Path of Orthodoxy” (chapter 5, part 2):

“The early Church did not know icons

in its modern,

dogmatic

meaning.

The beginning

of Christian art - painting of the catacombs - is

symbolic

in nature... This is

not

a depiction of Christ, saints or various events of sacred history,

as in an icon,

but an expression of certain thoughts about Christ and the Church.”

Representatives of Orthodoxy also agree that the church has no evidence

the early Christians' use of images in worship. True, some of the theologians are trying to convince ordinary believers that such evidence existed, but simply did not survive to our time. Here is how the Doctor of Theology, Orthodox Archbishop S. Spassky (1830-1904) wrote about this in his work “On the Veneration of Icons” (chapter “Holy Icons in the Second and Third Centuries”):

“From the second and third centuries of the Christian Church, persecuted and persecuted at this time, many sacred images, conventional or symbolic,

(below S. Spassky explains that this is catacomb creativity, as well as artistic decoration of vessels, lamps, rings and other objects. - Author's note);

clear and direct

sacred images have reached us (it is not clear what meaning S. Spassky wanted to put into the words “not very many”, when there are no other images at all, except for the catacomb ones, vaguely reminiscent of icons. He is probably saying again about the artistic design of the caves. - Author's note), 1st because Christians were afraid of giving themselves away to the pagans with these images, 2nd because they were afraid that the images themselves would not be desecrated by the pagans, 3rdly because that at that time there were quite a few Judaizing Christians who were against the sacred images themselves, in 4, not to mention the efforts of the pagans to destroy the images made by Christians, the most all-destructive time of subsequent centuries reduced many Christian icons of the second and third centuries.”

It is clear from the text that the archbishop is trying to explain the absence of liturgical images that have come down to us from the early church, citing various arguments. And of course, they are accepted by supporters of icon veneration. However, the facts remain facts. We have received a huge amount

lists of the Gospels, epistles of the apostles, works and letters of the first Christians, dating back to the 2nd and 3rd centuries, including

openly

denouncing paganism and Judaism. Since they survived, it means that the pagans and Jews could not destroy them. Therefore, it is not clear how and why absolutely all the relatively “harmless” icons of the 2nd and 3rd centuries in their huge numbers (if the first Christians used icons in worship, then, of course, their number would have been in the tens, hundreds of thousands), the “enemies of Christianity” destroyed everything fully? The question is also appropriate: “Where did the icons of the 4th and 5th centuries go, since at that time there was no longer any persecution of the church?” If we assume that all the early icons were destroyed by iconoclasts in the 8th and 9th centuries, then why did the icons of the 6th, 7th, 8th and 9th centuries remain? The answer to these questions is simple and logical: not a single icon of the 1st – 3rd centuries has reached us, because there could not have been any then, and in the 4th – 5th centuries the veneration of images, that is, at that time icons as such, only began to take shape. Apparently they didn't exist yet.

The icon-worshipers’ distrust of facts can be partly understandable, because their entire knowledge of God is inextricably linked with icons and relics. All their growth in the Lord took place next to these “shrines.” Therefore, many representatives of Orthodoxy are heartily attached to their favorite objects of worship and sincerely believe that Christians have always used them.

However, a number of authoritative theologians objectively evaluate historical facts. The famous Orthodox writer, graduate of the St. Sergius Orthodox Theological Institute Lepakhin V.V. (b. 1945) in his book “Icon and Image” directly says that icon-making began to take shape in Byzantine times

, that is, not earlier than the fourth decade of the 4th century (Byzantium began to be called the Eastern Roman Empire formed by Emperor Constantine in 330 with its capital in the city of Constantinople, formerly the city of Byzantium):

«Iconography

formed

on Byzantine soil

, and the theological justification for the veneration of icons crystallized

there

.”

There are also documents in the church that show the negative attitude of a number of prominent Christians of the early Byzantine period (after the fourth decade of the 4th century) towards the beginning of the introduction of images into the liturgical practice. It is worth noting that some Orthodox figures are making attempts to discredit historical evidence that in any way contradicts the canons accepted in the church. To do this, either the authority of the author is belittled by “discovering” in him sympathies for some heretical movement, or the very authorship of the work is called into question: they say, this is a forgery of later opponents of the teachings of the church. The latter, among other things, concerns the works of Epiphanius of Cyprus, Bishop of Salamis in Cyprus (d. about 403), who was against the use of images of Jesus and the apostles in the church, which he wrote about in the “Treatise against those who make images” (paragraph 12 ,16-18), letter to Emperor Theodosius (item 19,23), letter to John of Jerusalem (item 9).

“God as incomprehensible, inexplicable and indescribable cannot be depicted at all. He (Christ. - Author's note) Himself, during His coming to earth, did not command the production of

Your likeness, worship it or look at it;

such a command... is alien

to the Holy Scriptures,

turns

believers away from God and returns them to ancient

idolatry

. None of the ancient fathers dishonored Christ by making His images and hung them in the church or in their home; the same applies to images of prophets and apostles.”

Historical documents show that the idea of veneration

images of

the face of

Christ firmly captured the minds of church hierarchs only towards the end of the 7th century. 82nd rule of the VI Ecumenical (Orthodox) Council of Trulla 691-692. orders to replace in churches the images of the lamb, to which the Baptist John the Baptist pointed, with the human image of Jesus:

“On some honest icons, a lamb is depicted, shown by the finger of the Forerunner, which is accepted as the image of grace, through the law showing us the true lamb, Christ our God. While we honor the ancient images and canopies devoted to the Church as signs and foretellings of truth, we prefer grace and truth, accepting it as the fulfillment of the law. For this reason, so that through the art of painting the perfect thing may be presented to the eyes of all, we command from now on the image of the lamb who takes away the sins of the world, Christ our God, to be represented on icons according to human nature, instead of the old lamb;

and through this, contemplating the humility of God the Word, we are brought to the memory of His life in the flesh, His suffering, and saving death, and in this way the completed redemption of the world.”

Apparently, from that time on, iconoclasm began to gain momentum in the church. In 754, the VII Ecumenical Council was held in Constantinople, which was attended by 338 bishops. The Council condemned the veneration of icons, calling it idolatry in violation of the second commandment of the Decalogue:

«Painting

resembles Nestorius, dividing one Son and God the Word, who became incarnate for us, into two sons (Nestorianism was condemned at the 3rd Ecumenical Council in 431 - Author's note).

It resembles Arius, and Dioscorus, and Eutyches, and Severus, who taught that the two natures of the one Christ merged and mixed (Monophysitism was condemned by the Fourth Ecumenical Council in 451 - Author's note)

.

What crazy idea does a painter have for the sake of his pathetic pleasure to covet what is impossible to covet, that is, to depict with mortal hands what they believe in with their hearts and what they confess with their lips?

So the painter made an icon and called it Christ.

The name “Christ” is the name of both God and Man. Consequently, an icon is an icon of both God and Man. And thus he described how the indescribable Deity seemed to his feeble-mindedness to be a description of created flesh, or mixed an unfused compound and fell into the wicked delusion of fusion. He thus committed two blasphemies regarding the Divinity: describability and fusion.

Those who worship icons also fall under the same blasphemy .”

But already in 787, another council was convened, which declared the decision of the previous one invalid. The history of the adoption of such an important church decree is very interesting. Despite the decision of the Ecumenical Council of 754, some icon venerators were not going to give up, expecting a change in political or spiritual power. In 784, after the death of Patriarch Paul, the lay royal adviser Tarasius took over the leadership of the Eastern Church. According to a number of historians and religious scholars, his election was dictated solely by the desire of icon readers to use the influence of the secular rank on the emperor in order to give a new round of opposition to the iconoclasts. For more than thirty years (since 754), the worldwide church lived by the biblical doctrine that the veneration of images is idolatry. But the new lay patriarch initiated the convening of the next Ecumenical Council. It is worth noting that the Western (now Catholic) Church was not as involved in icon veneration as the Eastern (now Orthodox), which has remained to this day. Therefore, the new patriarch of the Eastern Church had to work hard to ensure that representatives of the Pope arrived at the council for a quorum. It was easier for a sanctified layman without a spiritual education corresponding to his rank to cede to Rome, since the long dogmatic confrontation between the Eastern and Western churches did not bother him much. The Patriarch quickly agreed to the conditions set by the Pope: the return of the confiscated possessions of the Roman Church; restoration of the Pope's jurisdiction over the ecclesiastical district seized under the iconoclasts. The Pope also officially declared that the See of St. Peter enjoys primacy on earth and was established in order to be the head of all the churches of God, and that only the name “universal Church” can apply to her. At the same time, he expressed bewilderment at the title of the Patriarch of Constantinople “ecumenical” and asked that this title never be used in the future.

The council was not convened immediately; its date had to be postponed, since bishops and iconoclast statesmen prevented its holding, even to the point of using state military force. And only when the iconoclasts were disarmed were the icon-worshippers able to convene a council. The cunning Empress Irina, who revered icons, sent garrisons supporting the iconoclasts to war in Asia Minor, supposedly to meet the Arabs, and instead brought in troops recruited in Thrace and Bithynia, where the views of the iconoclasts had not yet spread. Naturally, the new warriors blindly obeyed the empress.

It is worth noting that at the council of 787 in Nicaea, some of the dioceses were not fully represented, and representatives of some regions were not present at all. 257 bishops took part in the opening of the cathedral, and the conciliar message bears the signatures of 308 bishops. However, the council was recognized as Ecumenical with all the ensuing consequences. The bishops present at the council of 754 were spared and freed from severe punishments on condition of renunciation. Thus, a precedent was created and all councils were called into question, because one Ecumenical Council overturned the decision of another Ecumenical Council.

It must be said frankly that the Second VII Ecumenical Council, when issuing its doctrines, no longer tried to refer to the Bible, but explained its decisions by the need to observe church traditions.

Rules 7 and 9 of the VII Council of Nicaea in 787 read:

“Just as the image of honest icons was taken away from the Church, so some other customs were left, which should be restored and maintained according to the written law. For this reason, if any honest churches are consecrated without the holy relics of the martyrs, we determine: let the placement of the relics be performed in them with the usual prayer. If from now on a certain bishop appears, consecrating a temple without holy relics: let him be deposed, as if he had transgressed church traditions

.

All children's fables, and frantic mockery, and false writings written against honest icons,

must be given to the bishopric of Constantinople to be placed with other heretical books.

If anyone is found to be concealing such things, then a bishop, or a presbyter, or a deacon, let him be expelled from his rank, and a layman, or a monk, let him be excommunicated

from church communion.”

It is worth noting that the Western Church reacted ambiguously to the decision of the Second VII Ecumenical Council of 787. A few years later, the famous work The Book of Charles (Libri Carolini) appeared in the West on the controversial issue of venerating icons. In this work, as well as at the Frankfurt Council in 794 and the Paris Council in 825, all church service in front of icons was condemned, but the decoration of the church as such was not denied.

And the decision of the Second VII Ecumenical Council of 787 did not immediately take root in the Eastern Church. In 815, Emperor Leo and Patriarch Theodotus of Constantinople convened the 2nd Iconoclastic Council in the Church of Hagia Sophia, which abolished the decrees of the council of 787 and restored the definitions of the council of 754. The Council of 815, like Christians from the Western Church, did not call the decoration of the church idolatry, but was against lighting candles and lamps in front of images. After the council, bishops and abbots who venerated icons were again removed from service, and icons were removed from churches.

Iconoclasm lasted about a hundred years. Throughout this huge period of time, respected, eminent Christians sought the truth through negotiations and, unfortunately, bloodshed. Only in 843, at the Council of Constantinople, convened by Empress Theodora, the second VII Ecumenical Council of 787 won the final victory. In commemoration of this event, Orthodoxy established the holiday “Triumph of Orthodoxy,” which is celebrated annually on the first Sunday of Lent.

| CONTENT |

| Icons of Luke, their doubtfulness >> |

| Tags: Ecumenical Councils, ICON REVERENCE, iconoclasm, ANCIENT ICONS |

Iconoclasm in the Netherlands

Iconoclastic riots in the Netherlands began in 1566. The movement involved thousands of ordinary people, controlled by Calvinist consistories and Calvinist nobles. The protest took place as an open armed uprising directed against the Catholic Church, the Inquisition, the sale of indulgences, and the brutal persecution of heretics. The discontent of the people and noble circles was caused by the style of rule of the Spanish king Philip II, who established strict control over the Dutch provinces.

Participants in the iconoclastic movement destroyed many churches and noble estates, destroyed many icons, statues and church documents, and took away property from supporters of Catholicism. Simultaneously with the pogroms, people who had previously been declared heretics were released from places of detention. Against the backdrop of such events, Margaret of Parma, who acted as the Spanish governor in the Netherlands, issued a manifesto on August 23, 1566. It promised to eliminate the Inquisition and harsh laws against heretics, and provide greater freedoms to Calvinists. Subsequently, none of the reforms outlined in this document were ever implemented, since government officials pursued completely different goals.

After the release of the manifesto, the leaders of the popular uprising began to abandon previous ideas and swear allegiance to King Philip II. Left without their previous leadership, the iconoclasts were gradually defeated by Spanish troops. Many participants in the popular riots were imprisoned and tortured. The authorities who suppressed the iconoclast movement in the Netherlands re-established the previous regime and restored the unlimited power of the Catholic Church.

Krum's triumph

In 811, a catastrophe occurred. During a campaign against its northern neighbor, the Byzantine army successfully burned the Bulgarian capital of Pliska and began to return. And then... the Bulgarians attacked the Roman camp. The warriors were still sleeping and there was no battle as such - only a massacre, during which a huge number of ordinary soldiers and military leaders died. Many who fled drowned in the swamp. Emperor Nikifor also died - from his skull the Bulgarian Khan Krum, according to steppe tradition, made a beautiful bowl for a feast. The defeat at Pliska was perceived as analogous to the defeat at Adrianople (378) - for several centuries, emperors did not die on the battlefield.

The defeat was regarded as the wrath of God. In the new battle of Vershinik (813), the army was again defeated - the hastily recruited Byzantine troops fled in panic. Two defeats in a row were caused by low discipline and weak spirit of the soldiers.

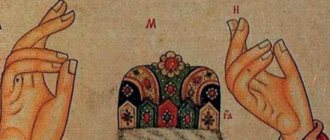

Iconoclasts John the Grammaticus and Bishop Anthony of Syllae fight with a fresco of Christ, 9th century (photo source)

The power in Constantinople changed. The new emperor Leo V the Armenian turned the ship of the empire around - icons began to be chopped with axes and burned at the stake. The decisions of the congress of 754 began to be implemented again. The new emperor was able to repel the invasion of Krum (he died) and made peace with the new khan. But he did not rule for long: Leo V was overthrown and killed, and his sons were mutilated.

Iconoclasts in other countries

Iconoclastic sentiments took place in medieval Europe, where they took the form of a religious and political movement. Here they not only fought against the worship of sacred images, but also criticized the undivided domination and oppression of the Church. As the iconoclasts argued, a believer can achieve salvation without religious symbolism and submission to the strict rules of Catholicism.

In the 16th century, the iconoclastic movement developed most intensely in Western Europe. During this period, riots by followers of Protestantism were recorded in Germany. In the Baltics, many Orthodox churches suffered from the aggressive actions of the iconoclasts.

In Russia, iconoclasm manifested itself in the form of open protest against the existing regime. After the Civil War of 1918, churches and icons were destroyed everywhere in the Soviet Union, and religion and its followers were persecuted in every possible way.

Consequences of the iconoclastic movement

The period of iconoclasm had both negative and positive consequences. The first is the destruction of numerous cultural monuments, the authors of which were talented craftsmen. Due to the events that took place, sculptures, masterpieces of fine art, and mosaics dedicated to religious themes disappeared. Some were able to survive partially, others were completely destroyed and did not reach subsequent generations.

The iconoclastic movement, which manifested itself most clearly in Byzantium, led to the strengthening of the Christian Church and its dogmas in many countries, including Rus'. After the victory of the iconoclasts, Byzantine statehood was defined, and a stable relationship was formed between the clergy and representatives of the sovereign power.

Christian icons originated in the 2nd century

Christians painted the first icons in the 2nd century. These images have not survived. They were predominantly symbolic in nature. Christ could well have been depicted as some kind of animal. Remember the lamb in the Revelation of John the Theologian? Similar animals were painted in abundance.

Mostly it was a wall painting, rather than a separate image.

VI

the earliest icons that have survived to this day - this century

The oldest Christian icons that have come down to us date back to the 6th century. They painted the walls of temples.

Attitude to icons in our time

Today, veneration of icons is an important church rule for most Christians. At the same time, there are religious movements that deny the need to worship holy images.

The main movement of this kind is Protestantism, whose adherents, like the Byzantine iconoclasts, call the veneration of holy faces nothing more than idolatry. Protestants refer to certain sections of the Holy Scriptures and claim that Orthodox Christians pray before icons on their knees, kiss them and treat them as idols, which is contrary to the Bible. Their views are to a certain extent reminiscent of the Muslims, who do not recognize any religious images.

In Orthodoxy, Protestant claims are refuted. The clergy remind us that icons depict the true God. Believers worship not the product of human hands, but the holy prototype. Icons remind people of the Lord, the Son of God, the Most Pure Mother of God, but do not replace Their true immaterial essence.

Failure of the Reformation

Although iconoclasm tried to solve the military and economic problems of the empire, it rather increased them. The Empire actually lost Italy and the Roman pontiffs, who came under the protection of the Carolingians. Byzantium increasingly pupated within its own borders, becoming a regional factor from a pan-European factor.

The first reformation failed. Trying to preserve the feminine army, the basileus attacked the church, but this only embittered the population of the empire. Riots, uprisings and conspiracies were the eternal companions of the Isaurian (717-802) and Amorian (820-867) dynasties. And the uprising of Thomas the Slav generally brought the empire to the brink of destruction. At the same time, the basileus never solved the problem of impoverishment of small peasants. The Stratiots were no longer able to purchase the necessary equipment on their own - they were again given weapons at state expense.

Already under Leo VI of the new Macedonian dynasty, the army of the East alone absorbed up to 40 percent of government spending annually. The military and economic power of the empire was greatly undermined, and the monastic possessions remained an internal offshore.

In 917, the Byzantine army was defeated by the Bulgarians at Aheloy. But even this defeat did not revive the idea of iconoclasm.