Detail of the onion domes of St. Basil's Cathedral in Moscow (Russia), one of the most striking examples of Russian architecture

Taj Mahal in Agra (India), an example of Mughal architecture

Bow dome

(Russian: Onion Head,

lúkovichnaya Glava

, compare Russian: luk,

Luk

, "bow") is a dome whose shape resembles a bow and is generally associated with the Russian architectural style. [1] Such domes are often larger in diameter than the tolobat on which they sit, and their height usually exceeds their width. These convex structures smoothly turn into a point.

This is a typical feature of churches belonging to the Russian Orthodox Church. There are similar buildings in other Eastern European countries and sometimes in some Western European countries, as in Germany Bavaria (German: Zwiebelturm

(literally "bow tower") Austria, northeastern, Italy. Buildings with domes are also found in the eastern regions of Central and South Asia and the Middle East. However, older houses outside of Russia usually do not have the characteristic typical structure of Russian onion design. Probably the origin lies in the original architectural style of the ancient Russian tribes.

Other types of Eastern Orthodox domes include helmet domes

(for example, the Assumption Cathedral in Vladimir), Ukrainian

pear domes

(St. Sophia Cathedral in Kiev) and

bud domes

(St. Andrew's Church in Kiev) or onion helmet. a mixture like St. Sophia Cathedral in Novgorod.

History[edit]

Onion domes in the Church of the Resurrection of Christ, Kostroma (1652)

It is not entirely clear when and why onion domes became a characteristic feature of Russian architecture. The recurve bow style appeared outside of Russia, both in the Western world and in the East at a later time. [2] But there are still several theories according to which the shape of the Russian bow was influenced by countries of the East, such as India and Persia, with which the Russian population and culture have always been in cultural exchange throughout history. Byzantine churches and the architecture of Kievan Rus were characterized by wider flat domes without a special frame erected above the drum. In contrast to this ancient form, each drum of a Russian temple is topped with a special structure of metal or wood, lined with sheet iron or tiles, while onion architecture is generally very curved. In Russian architecture, the dome shape was used not only for churches, but also for other buildings. [ citation needed

]

By the end of the nineteenth century, most Russian churches before Peter's period had onion domes. The largest onion domes were erected in the 17th century in the vicinity of Yaroslavl, which, by the way, is famous for its large onions. Many had more elaborate bud-shaped domes, the shape of which was derived from Baroque models of the late seventeenth century. Pear-shaped domes are usually associated with Ukrainian Baroque, while conical domes are associated with Transcaucasian Orthodox churches. [ citation needed

]

Russian theory

The works of Russian researchers indicate a version of the gradual transformation of the Byzantine dome into a Russian onion. The reasons for evolution are climatic conditions and traditions of wooden architecture.

The same factors influenced the development of stone architecture in Ancient Rus', so that by the 13th century only the constructive system of the cross-domed church remained from Byzantine influence.

A.P. Novitsky notes that the eastern domes (Persia, India, Byzantium) have a shape that gives complete stability. “ The shape of the bulb is exactly the opposite of this requirement and cannot have any stability. It can be an exclusively decorative form and can be built either in the form of a blind dome, or using rafters

". (Novitsky A.P. Onion-shaped form of Russian church domes. Its origin and development // Antiquities. Proceedings of the commission for the preservation of ancient monuments. - M., 1909. - T. III. p. 856)

Traditional view[edit]

Onion domes of St. Basil's Cathedral

Allegedly [ original research?

] On Russian icons painted before the Mongol invasion of Rus' in 1237–1242, there are no churches with onion domes.

Two highly revered pre-Mongol churches that were rebuilt - the Assumption Cathedral and the Cathedral of St. Demetrius in Vladimir - are decorated with golden helmets. Restoration work at several other ancient churches has revealed fragments of former helmet domes beneath new onion domes. [ citation needed

] This was determined [

by whom?

] that onion domes first appeared in Rus' during the reign of Ivan the Terrible (r. 1533-1584).

The domes of St. Basil's Cathedral have not been altered since the reign of Ivan's son Fyodor I (r. 1584–1598), indicating the presence of domes in sixteenth-century Russia. [ citation needed

]

Some scholars suggest that the Russians borrowed onion domes from Muslim countries, perhaps from the Khanate of Kazan, whose conquest in 1552 Ivan the Terrible commemorated with the construction of St. Basil's Cathedral. [3] Eight of the nine domes of St. Basil's Cathedral represent each attack on Kazan. The ninth dome was built 36 years after the siege of Kazan as Ivan’s tomb. The ornate decoration of these domes is bright in color and bold in shape, as they are decorated with pyramids and stripes, as well as many other designs seen on cathedrals other than St. Basil's. [4] Some scholars believe that onion domes first appeared in Russian wooden architecture over tented churches. According to this theory, onion domes were strictly utilitarian, since they prevented the accumulation of snow on the roof. [5]

Modern look[edit]

The wooden churches on Kizhi and Vytegra have as many as twenty-five onion domes.

In 1946, historian Boris Rybakov, analyzing miniatures from ancient Russian chronicles, noted that in most of them, starting from the 13th century, churches are depicted with onion domes, and not with helmet ones. [6] Nikolai Voronin, a major authority on pre-Mongol Russian architecture, supported his view that onion domes existed in Russia as early as the 13th century, although they apparently could not have been widespread. [7] These finds showed that Russian onion domes could not have been imported from the East, where onion domes did not replace spherical domes until the fifteenth century. [ citation needed

]

Sergei Zagraevsky, historian of modern art, has researched hundreds of Russian icons and miniatures since the 11th century. He came to the conclusion that most icons painted after the Mongol invasion of Rus' depicted only onion domes. The first onion domes are depicted in some images from the 12th century (two miniatures from the Dobrylov Gospel). [8]He found only one icon from the late fifteenth century with a dome resembling a helmet rather than a bulb. His findings led him to dismiss fragments of helmet domes discovered by restorers under modern onion domes as post-Petrine stylizations intended to reproduce the familiar shapes of Byzantine domes. Zagraevsky also pointed out that the oldest depictions of the two Vladimir cathedrals present them as having onion domes before they were replaced by classical helmet domes. He explains the widespread appearance of onion domes at the end of the 13th century by the general emphasis on verticality characteristic of Russian church architecture of the late 12th and early 15th centuries. [9]At that time, the porches, pilasters, vaults and drums were designed to create vertical support to make the church appear taller than it actually was. [10] It seems logical that elongated or onion domes were part of the same proto-Gothic trend to achieve a pyramidal, vertical emphasis. [ citation needed

] [11]

Excerpt characterizing Onion Chapters

“She pulled out all the stops, gave three runs on her own,” Nikolai said, also not listening to anyone, and not caring whether they listened to him or not. - What the hell is this! - said Ilaginsky the stirrup. “Yes, as soon as she stopped short, every mongrel will catch you from stealing,” said Ilagin at the same time, red-faced, barely catching his breath from the galloping and excitement. At the same time, Natasha, without taking a breath, squealed joyfully and enthusiastically so shrilly that her ears were ringing. With this screech she expressed everything that other hunters also expressed in their one-time conversation. And this squeal was so strange that she herself should have been ashamed of this wild squeal and everyone should have been surprised by it if it had been at another time. The uncle himself pulled the hare back, deftly and smartly threw him over the back of the horse, as if reproaching everyone with this throwing, and with such an air that he didn’t even want to talk to anyone, sat on his kaurago and rode away. Everyone except him, sad and offended, left and only long after could they return to their former pretense of indifference. For a long time they looked at the red Rugay, who, with his hunchbacked back and dirt stained, rattling his iron, with the calm look of a winner, walked behind the legs of his uncle’s horse. “Well, I’m the same as everyone else when it comes to bullying. Well, just hang in there!” It seemed to Nikolai that the appearance of this dog spoke. When, long after, the uncle drove up to Nikolai and spoke to him, Nikolai was flattered that his uncle, after everything that had happened, still deigned to speak with him. When Ilagin said goodbye to Nikolai in the evening, Nikolai found himself at such a far distance from home that he accepted his uncle’s offer to leave the hunt to spend the night with him (with his uncle), in his village of Mikhailovka. - And if they came to see me, it would be a pure march! - said the uncle, even better; you see, the weather is wet, the uncle said, if we could rest, the countess would be taken in a droshky. “Uncle’s proposal was accepted, a hunter was sent to Otradnoye for the droshky; and Nikolai, Natasha and Petya went to see their uncle. About five people, large and small, courtyard men ran out onto the front porch to meet the master. Dozens of women, old, big and small, leaned out from the back porch to watch the approaching hunters. The presence of Natasha, a woman, a lady on horseback, brought the curiosity of the uncle's servants to such limits that many, not embarrassed by her presence, came up to her, looked into her eyes and in her presence made their comments about her, as if about a miracle being shown, which is not a person, and cannot hear or understand what is said about him. - Arinka, look, she’s sitting on her side! She sits herself, and the hem dangles... Look at the horn! - Fathers of the world, that knife... - Look, Tatar! - How come you didn’t somersault? - said the bravest one, directly addressing Natasha.

Symbolism[edit]

Main article: Symbolism of domes

Group of three blue domes in the Church of St. Simeon of the Wonderful Mountain in Dresden, Germany

Until the eighteenth century, the Russian Orthodox Church did not attach much symbolism to the appearance of the church. [12] However, onion domes are believed to symbolize burning candles. In 1917, the famous religious philosopher Prince Evgeniy Trubetskoy argued that the onion-shaped domes of Russian churches cannot be explained rationally. According to Trubetskoy, the drums, topped with tapering domes, were deliberately cut to resemble candles, expressing a certain aesthetic and religious attitude. [13] Another explanation states that the onion dome was originally seen as a shape reminiscent of the aedicula (cubiculum) in the Church of the Holy Sepulcher in Jerusalem. [14]

Onion domes often appear in groups of three, representing the Holy Trinity, or five, representing Jesus Christ and the four evangelists. The free-standing domes represent Jesus. Vasily Tatishchev, who was the first to record such an interpretation, strongly disapproved of it. He believed that the five-domed design of churches was promoted by Patriarch Nikon, who liked to compare the central and highest dome with himself, and the four side domes with the four other patriarchs of the Orthodox world. There is no other evidence that Nikon ever took this view. [ citation needed

]

Domes are often brightly colored: their colors may informally symbolize various aspects of religion. The green, blue and gold domes are sometimes considered symbols of the Holy Trinity, the Holy Spirit and Jesus respectively. Black spherical domes were once popular in the snowy north of Russia. [ citation needed

]

Opinion of foreign historians

Western architectural historians associated the appearance of onion domes in Rus' with Eastern influence. The most popular ideas were the Indian or Tatar origin of the onion dome.

For example, the Scot J. Ferguson wrote: “The Tatars brought with them the onion-shaped dome, the Russians accepted it and hold on to it to this day, not noticing that this is a symbol of their enslavement by a race they despise. With the exception of this one form, their architecture is nothing more than a weak, unsuitable copy of the Byzantine one.” (Fergusson JA History of Architecture. Vol. II – London, 1867. – p. 50.)

Internationally[edit]

Asia[edit]

The onion dome is not only found in Russian architecture: it was also widely used in Mughal architecture, which later influenced Indo-Saracenic architecture. Outside India, it is also used in Iran and other countries in the Middle East and Central Asia. In the late 19th century, the Dutch built the Baiturrahman Great Mosque in Aceh, Indonesia, with an onion-shaped dome. Since then, the dome shape has been used in many mosques in Indonesia. [ citation needed

]

- Badshahi Mosque in Lahore (Pakistan)

- Baiturrahman Great Mosque of Aceh (Indonesia)

- Ubudia Mosque in Kuala Kangsar, Perak (Malaysia)

- Pagoda of Chongjue Temple in Shandong (China)

Europe [edit]

Western and Central countries[edit]

Baroque domes in the shape of onions (or other vegetables or buds) were also common in the Holy Roman Empire. The first was built in 1576 by the architect John Hall (1512–1594) in the church of the monastery of the Franciscan Sisters of Maria Stern in Augsburg. Typically made from copper sheet, Domes appear on Catholic churches throughout southern Germany, the Czech Republic, Austria and Sardinia and northeastern Italy. Onion domes were also a favorite of 20th century Austrian architects. Friedensreich Hundertwasser. [ citation needed

]

- St. Leonard's Church in Mittersill (Austria)

- St. Mary's Church in Munich (Germany)

- Dome of the bell tower of the Cathedral of Oristano, Sardinia (Italy)

- San Lazzaro degli Armeni from Venice (Italy)

Southern countries[edit]

- Dome of the Church of St. Athanasius in Seltsi (North Macedonia)

America[edit]

The world's only Corn Palace, a tourist attraction and basketball arena in Mitchell, South Dakota, also features onion domes on the roof of the building.

- The world's only corn palace in Mitchell (South Dakota, USA)

- Longwood in Natchez (Mississippi, USA)

- Fuller Block in Springfield (Massachusetts, USA), domes have since been removed

Notes and links[edit]

- Block, Eric (2010). Garlic and other allium crops: knowledge and science

. Royal Society of Chemistry. ISBN 9780854041909. - Block, Eric (2010). Garlic and other allium crops: knowledge and science

. Royal Society of Chemistry. ISBN 9780854041909. - Shvidkowski, D. S. (2007). Russian architecture and the West

. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-10912-2. - Bridge, Nicole (2015). Architecture 101: The Essential Guide to Building Styles and Materials

. Avon, MA: Adams Media. paragraph 88. ISBN 978-1-4405-9007-8. - A.P. Novitsky. Onion-shaped heads of Russian churches. In the book: Moscow Archaeological Society. Proceedings of the commission for the preservation of ancient monuments. T. III. Moscow, 1909

- B.A. Rybakov. “Windows into a disappeared world (about the book by A.V. Artsikhovsky “Ancient Russian sources of miniatures as historical”). In the book: Reports and communications of history. faculty of Moscow State University. Vol. IV. M., 1946. P. 50.

- N.N.Voronin. Architectural monument as a historical source (notes on the formulation of the question). In the book: Soviet archeology. Vol. XIX. M., 1954. P. 73.

- S.V. Zagraevsky. Forms of domes of ancient Russian churches. Published in Russian: Zagraevsky S.V. Forms of domes (domes) of ancient Russian churches. M.: Alev-V, 2008.

- G.K.Wagner. On the uniqueness of the style of formation in the architecture of Ancient Rus' (return to the problem). In the book: Architectural heritage. Vol. 38. M., 1995. P. 25.

- See, for example, the most authoritative review of early Russian architecture: P.A. Rappoport. Old Russian architecture. St. Petersburg, 1993.

- Another important consideration proposed by Zagraevsky links the onion-like shape of Russian domes to the weight of traditional Russian crosses, which are much larger and more complex than those used in Byzantium and Kievan Rus. Such heavy crosses would fall aground during a storm if they were not attached to large stones traditionally placed inside the elongated domes of Russian churches. It is impossible to place such a stone inside a flat Byzantine-type dome. [ citation needed

] - Buseva-Davydova I.L. Symbol of architecture according to ancient Russian writings of the 11th-17th centuries.

// Hermeneutics of Old Russian literature. XVI - early XVIII centuries. Moscow, 1989. - “The Byzantine dome over the church represents the vault of heaven above the earth. On the other hand, the Gothic spire expresses an unbridled vertical thrust that lifts huge masses of stone towards the sky. In contrast, our native onion dome can be likened to a tongue of fire, topped with a cross and tapering towards the cross. When we look at the bell tower of Ivan the Great, it’s as if we see a giant candle burning over Moscow. Kremlin cathedrals and churches with their multiple domes look like huge chandeliers. The shape of the bow is a result of the idea of prayer as a soul burning towards heaven, which connects the earthly world with the treasures of the afterlife. Every attempt to attribute the onion-shaped shape of our church domes to utilitarian considerations (such as the need to prevent snow from accumulating on the roof) fails to take into account the most important point - the aesthetic significance of onion domes to our religion. In fact, there are many other ways to achieve the same utilitarian result, such as spiers, spiers, cones. Of all these forms, why did ancient Russian architecture settle on the onion dome? Because the aesthetic impression produced by the onion dome corresponded to a certain religious attitude. The meaning of this religious-aesthetic feeling is subtly expressed by the popular saying - “blazing with ardor - when they talk about church domes.” - See E.N. Trubetskoy. Three essays about the Russian icon. 1917. Novosibirsk, 1991. P. 10.

- Lidov A.M. Jerusalem Edicule. On the origin of onion heads. // Iconography of architecture. Moscow, 1990.

LiveInternetLiveInternet

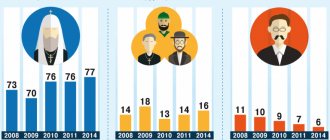

Onion domes are the most characteristic distinctive feature of Russian churches of all times.

Everyone who gets acquainted with Russian architecture for the first time pays attention to this unusualness. Heterogeneous opinions about their origin were systematized at the beginning of the twentieth century by the art historian A.P. Novitsky. He identified 2 main theories around which almost all the opinions expressed were grouped.

Western architectural historians associated the appearance of onion domes in Rus' with Eastern influence. The most popular ideas were the Indian or Tatar origin of the onion dome. For example, the Scot J. Ferguson wrote: “The Tatars brought with them the onion-shaped dome, the Russians accepted it and hold on to it to this day, not noticing that this is a symbol of their enslavement by a race they despise. With the exception of this one form, their architecture is nothing more than a weak, unsuitable copy of the Byzantine one.” (Fergusson JA History of Architecture. Vol. II – London, 1867. – p. 50.)

The works of Russian researchers indicate a version of the gradual transformation of the Byzantine dome into a Russian onion. The reasons for evolution are climatic conditions and traditions of wooden architecture. The same factors influenced the development of stone architecture in Ancient Rus', so that by the 13th century only the constructive system of the cross-domed church remained from Byzantine influence.

A.P. Novitsky notes that the eastern domes (Persia, India, Byzantium) have a shape that gives complete stability. “ The shape of the onion is exactly the opposite of this requirement and cannot have any stability. It can be an exclusively decorative form and can be built either in the form of a blind dome, or using rafters

". (Novitsky A.P. Onion-shaped form of Russian church domes. Its origin and development // Antiquities. Proceedings of the commission for the preservation of ancient monuments. - M., 1909. - T. III. p. 856)

Today, historians say that onion domes appear in ancient Russian stone architecture at the turn of the 16th–17th centuries. This opinion is widespread because not a single monument is known in which the onion dome could be accurately dated earlier than the end of the 16th century.

The eastern facade of the Archangel Cathedral in the Kremlin in a painting by Giacomo Quarenghi (1797). It was built in 1508 according to the design of the architect Aleviz Novy. Author: Giacomo Quarenghi - arthermitage.org, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=528441

In the seventeenth century. onion domes are becoming an almost obligatory feature of every Orthodox church. This is explained by the general trend towards greater decorativeness in the art of this century.

Alexey Mikhailovich Lidov, a Russian art historian and Byzantine scholar, offered his own version. He believes that " the onion dome is not a formally decorative, but an iconographically significant motif with a specific symbolic content."

(A.M. Lidov. Jerusalem Edicule. On the origin of onion domes. Iconography of architecture, edited by A.L. Batalov. M., 1990, p. 57-68)

In his opinion, the “bizarre and in some sense unnatural architectural form” significantly complicates the task of builders. It is unlikely that a simple desire for decorativeness or the evolution of the shape of the dome can be the reason for the construction of a special structure over the vault.

In addition, as a religious scholar, A. M. Lidov believes that the medieval religious way of thinking conflicts with purely decorative experiments in the most important part of the temple - the dome. However, the idea of reproducing a symbolically significant sample could inspire architects and change the accepted form.

Analyzing the iconographic motif of the onion dome in Eastern Christian art before the 17th century, he finds this example. A century before the approval of onion domes in ancient Russian architecture, in I486, the shape of an onion was on the Greater and Lesser Zions of the Assumption Cathedral of the Moscow Kremlin.

Greater and Lesser Zions of the Moscow Assumption Cathedral of 1486

Zion (zion) or “Jerusalem” in theory repeats in miniature the architecture of the Jerusalem Temple and is intended for storing the Gifts; used in Byzantium and Rus' during especially solemn services. With its help, a symbolic connection was established with the place of Christ’s burial and resurrection.

The Zions stored in the main cathedral of the country could well serve as a direct source of a new architectural solution, Lidov believes.

At the beginning of the 4th century, the cuvuklia (Greek Κουβούκλιον - canopy) of the Church of the Holy Sepulcher was erected over the tomb of Jesus. The one standing today is the result of later alterations and a radical reconstruction of the entire complex, carried out by the crusaders in the middle of the 12th century.

Church of the Holy Sepulcher. The dome is like an onion.

However, based on texts and images, it is possible to recreate the appearance of an ancient structure. Kondakov N.P. - historian of Byzantine and Old Russian art, archaeologist, creator of the iconographic method of studying monuments - compared images with texts from the period of the 4th-6th centuries.

Lidov quotes him in his work: “ A light tent-like structure, a kind of canopy, the top of which is covered by a round dome, divided into six conical sections by six ribs and covered with six arches along the valance, the lower part is either supported by columns or decorated with them along the facade.

«

From the second half of the 11th century. Images of onion domes have become widespread in the art of the Orthodox world. Moreover, the onion dome is found not only in specific reproductions of the Jerusalem temple, but also in any depiction of the church.

Lidov explains this by the enormous importance that Byzantium attached to the completion of the restoration (renovation) of the Church of the Holy Sepulcher by Emperor Constantine Monomakh in 1042–1048.

It should be remembered that in 1054 the Christian Church split into Catholic and Orthodox. After a radical alteration of the edicule by the Latin crusaders in the middle of the 12th century. the onion dome becomes a stable iconographic motif that retains the status of a universal sign of the internal unity of each Orthodox Church with the First Church of the Holy Sepulcher.

The symbolically capacious motif of the onion dome becomes widespread in ancient Russian art. Among the earliest examples, one can note a miniature from the Dobrilov Gospel of 1164, in which a bulbous church dome with a characteristic imitation of a scaly covering is depicted above the evangelist.

“Luke the Evangelist” is a miniature of Dobrilov’s Gospel (1164).

According to the researcher, to understand the iconographic motif of the onion, it is essential to understand that the Church of the Holy Sepulcher, which arose on the site of the atoning sacrifice and resurrection of Christ, was interpreted by theologians as the New Jerusalem, the visible embodiment of the Kingdom of Heaven.

The rapid and widespread adoption of onion domes in stone architecture of the 17th century. exclusively in Russian churches leads the author to believe that the process was stimulated by a specific initiative of the central government. If this is so, then the idea of the times of Boris Godunov (1598 - 1605) “Moscow is the second Jerusalem” takes on a completely special meaning.

Accepting the iconographic hypothesis, we can say that the onion domes of Orthodox churches internally unite them with the main shrine of the Christian world.

+ + +