Young Pope

Octavian Tuscolo - the future Pope John XII - was the son of the Duke of Spoleto, a Roman senator and consul of Alberich II. In 932, he eliminated all his rivals (among whom were his mother, brother and stepfather) and gained power over Rome. Alberich had full control of the Holy See and placed the papal tiara on the people under him. At the end of his life, he decided to transfer both secular and spiritual power over Rome to his son. Upon ascending the throne, Octavian took the name John, thus becoming the first Pope in history to change his name during his election (some researchers believe that Pope John II, who ruled in the 6th century, took a different name for the first time).

Historians hardly know what Octavian did before he became Pope. In one of the editions of the collection of acts of the Roman popes, Liber Pontificalis, it is said that Octavian was a cardinal deacon of the Roman diaconia of the Virgin Mary and served in the Basilica of Santa Maria in Domnica. Upon ascending the throne, the pope made an attempt to expand the territories subordinate to Rome in the south. His military campaigns were unsuccessful, and control over the important port city of Salerno was completely lost. Failures in the career of a warrior did not turn the young dad to spiritual quests. On the contrary, having returned to Rome, he indulged in revelry and debauchery.

Portrait of Pope John XII

As Stendhal writes in his Walks in Rome, “... Pope John XII desecrated himself with blasphemy, murder and incest... all the beautiful women of Rome were forced to flee their homeland so as not to be subjected to violence... The Lateran Palace, once the refuge of saints, became a place debauchery, where John kept, together with other women of cheerful morals, the sister of his father’s concubine as his own wife.” Not limiting himself to this, the pope “drank the health of the devil, called on the demons Jupiter and Venus to help him in gambling.”

The 130th Pope was far from the first pope who did not care about his sacred duties. A whole series of “deputies of God on Earth” who preceded John indulged in fornication. Since 904, the period of so-called pornocracy lasted in Rome, when the papal throne was occupied either by the lovers of easy-going representatives of the aristocratic family of Theophylacts, or by the voluptuous henchmen of Alberich II.

In addition to bathing in all kinds of pleasures, Pope John XII continued to engage in foreign and domestic politics, but it turned out very badly for him. Under his leadership, Rome, which had long forgotten about its former greatness, fell into even greater decline. City taxes went to satisfy the papal needs in the field of gambling and sexual pleasures. The weakness of the position of the Eternal City was immediately sensed by the cruel and treacherous King Berengar II of Israel, who in 959 captured the Duchy of Spoleto and began to plunder the papal lands north of Rome.

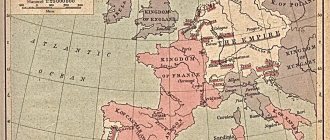

Since John XII lacked the military power to defend himself on his own, he had to seek support from one of the most influential sovereigns of the time - the King of Germany, Duke of Saxony and Franconia Otto I. The latter quickly defeated Berengar's forces and entered Rome almost unopposed in January. 962 years old. Otto, who had long dreamed of restoring the empire of Charlemagne, received the crown of the Holy Roman Empire in gratitude from the pope. “Thus the most despicable of all pontiffs,” the historian John Norwich caustically observes, “restored the empire of Charlemagne, which was destined to last for at least nine and a half centuries.” Indeed, in the interest of the moment, wanting to profit from Otto's favor, John XII helped found the Holy Roman Empire, a great power that only collapsed as a result of the Napoleonic Wars.

Otto I and Pope John XII

Two weeks after his coronation in St. Peter's Basilica, Otto I left Rome. Before this, he gave the young pope a series of fatherly instructions, convincing him to abandon his dissolute lifestyle. Otto's moralizing infuriated the pope. Behind the emperor's back, he began to negotiate with Berengarius' son Adalbert, promising him Otto's imperial crown.

The good-natured Otto initially did not believe these rumors, but when he was told that Adalbert had arrived in Rome, and unimaginable orgies were taking place in the Lateran Palace, he decided to march with an army on the Eternal City. John XII, having learned about Otto's approach, together with Adalbert, stole all the money remaining in the treasury and fled. The emperor freely entered the city and soon assembled a synod. About a hundred of the most prominent bishops came to see him. Numerous evidence of the pope's non-Christian behavior on the throne of St. Peter was announced. According to the chronicler, John XII was accused of “he openly went hunting... blinded his spiritual father Benedict... became responsible for the death of Cardinal Subdeacon John, ordering his castration... set houses on fire and appeared in public girded with a sword, wearing a helmet and armor "

Otto I. Image by Lucas Cranach the Elder

Otto sent the pope a letter asking him to return to Rome to justify himself, but John responded by threatening to excommunicate the synod participants from the church and deprive them of their positions. The pontiff wrote his address to them in Latin with errors, which caused laughter among the representatives of the higher clergy. A number of other funny incidents led to the fact that the runaway dad was simply no longer taken seriously. On December 6, 963, at the request of Otto, the council elected a new head of the Church - Leo VIII. John XII, in turn, was convicted of a vicious life and deposed.

However, he was not going to give up the papal throne so easily. In January 964, as soon as Otto and his army left Rome, John returned to the city. All decisions of the synod were annulled, and many of its participants faced torture and painful death. The new synod, assembled by John, excommunicated Leo VIII, who managed to find refuge with Otto. The emperor was distracted by the fight with other opponents and was able to prepare a new campaign against Rome only at the beginning of May 964. On the way, he learned that the young and dissolute father had died. The exact cause of his sudden death is unknown. According to some sources, he was overtaken by an apoplexy during love pleasures; according to others, dad was stabbed to death by the husband of one of his mistresses. The chronicler of Otto I wrote that perhaps Satan himself killed John with a blow to the head and took his faithful servant to hell.

Popes John Paul II and John XXIII declared saints

In Poland, the canonization of the first pope of Polish origin, John Paul II, who bore the name Karol Wojtyla in the world, was greeted with jubilation.

John Paul II was the first non-Italian head of the Roman Catholic Church in 450 years. Researchers call his pontificate exceptional, taking into account his spiritual contributions, the number of canonizations, pilgrimages and visits. In total, he made 104 trips, visiting all inhabited continents, paying special attention to regions where poverty and hunger reign and human rights to freedom and a dignified existence are violated. During his ministry, 300 million people converted to Catholicism. Karol Wojtyła died on the 9666th day of his pontificate.

In Russia, John XXIII (November 25, 1881 - June 3, 1963, pope since 1958) is less known than John Paul II: the pontificate of Pope Roncalli fell during a period of intensified struggle against religion in the USSR.

Nevertheless, John XXIII made a serious attempt at rapprochement with Moscow: on March 7, 1963, he gave an audience to Khrushchev’s daughter Rada Nikitichna and her husband Alexei Adzhubey, editor-in-chief of Izvestia and member of the CPSU Central Committee.

John XXIII was the first pontiff who began to advocate the peaceful coexistence of states with different social systems. He officially recognized the revolution in Cuba. It was John XXIII who made the first contact with representatives of other Christian churches. When the Cuban Missile Crisis broke out, the pope sent a personal letter to John Kennedy urging him not to escalate the conflict to war. Many historians believe that since Kennedy was a Catholic, the letter from the Roman pontiff was perhaps the decisive deterrent.

It was known about John XXIII's intention to establish diplomatic relations with the Soviet Union. He stated this in a confidential conversation with Nuncio Roberti.

An interesting detail: he closely followed the successes of the USSR in space exploration and repeatedly wished success to the Soviet cosmonauts in his sermons.

Pope Roncalli went down in history as a reformer of the church; the main act of his pontificate was the convening of the Second Vatican (XXI Ecumenical) Council.

This is the last of the cathedrals of the Catholic Church, opened in 1962 and continued until 1965 (during which time John XXIII died and the cathedral closed under Pope Paul VI). The council adopted a number of important documents related to church life - four constitutions, nine decrees and three declarations.

It is the convening of this council that Pope Francis considers the main work of the life of John XXIII. In many ways, the decision to canonize Roncalli is a programmatic one for Pope Bergoglio, who has already declared himself as a reformer of the church.

Literature

- Chronica universalis Metensis an. 1099 // MGH. SS. T. 24. P. 514;

- Chronica minor auctore minorita Erphordiensi an. 900 // Ibid. P. 184;

- Stephanus de Borbone. Tractatus de diversis materiis praedicabilibus. Turnhout, 2002. (CCCM; 124);

- Martini Oppaviensis Chronicon Pontificum et Imperatorum // MGH. SS. T. 22. P. 428-429;

- Flores temporum // Ibid. T. 24. P. 243;

- Geoffroy de Courlon. Le Chronique de ÍAbbaye de Saint-Pierre-le-Vif / Ed. G.Julliot. Sens, 1876;

- Boccaccio G. Famous Women / Ed. V. Brown. Camb. (Mass.), 2001. P. 436-441;

- Platina B. Historia. 1600. P. 133-141;

- Iacopo da Varagine e la sua cronaca di Genova dalle origini al 1297 / Ed. G. Monleone. R., 1941. Vol. 1. P. 268-269.

- Döllinger JJ Die Papst-Fabeln des Mittelalters. Münch., 1863;

- Müntz E. La légende de la Papesse Jeanne dans l'illustration des livres, du XVe au XIXe siècle // La Bibliofilia. Firenze, 1900-1901. Vol. 2. P. 325-329;

- Bilbasov V. A. Woman-Dad: Middle Ages. legend // He. East. monographs. St. Petersburg, 1901. T. 1. P. 119-164;

- Conway BL The Legend of Pope Joan // The Catholic World. 1914. Vol. 99. P. 792-798;

- Kraft W. Die Päpstin Johanna: Eine Motivgeschichtliche Untersuchung: Diss. Fr./M., 1925;

- D'Onofrio C. La Papessa Giovanna: Roma e papato tra storia e leggenda. R., 19792;

- Morris J. Pope John VIII: An English Woman, alias Pope Joan. L., 1985;

- Tinsley BS Pope Joan Polemic in Early Modern France: The Use and Disabuse of Myth // The Sixteenth Century Journal. Kirksville, 1987. Vol. 18. N 3. P. 381-398;

- Boureau A. La papesse Jeanne: Formes et fonctions d'une légende au Moyen Âge // CRAI. 1984. Vol. 128. N 3. P. 446-464;

- idem. La papesse Jeanne. P., 1988;

- Pardoe R., Pardoe D. The Female Pope: The Mystery of Pope Joan. Wellingborough, 1988;

- Gössmann E. Mulier Papa: Der Skandal eines weibliches Papstes: Zur Rezeptionsgeschichte der Gestalt der Päpstin Johanna. Münch., 1994;

- Hotchkiss VV The Legend of the Female Pope in the Reformation // Acta Conventus Neo-Latini Hafniensis: Proc. of the 8th Intern. Congress of Neo-Latin Studies / Ed. Rh. Schur et al. Binghampton, 1994. P. 495-505;

- Stanford P. The Legend of Pope Joan: In Search of the Truth. NY, 1999;

- Aubert R. Jeanne (1) // DHGE. T. 27. Col. 908-912;

- DuBruck EE Pope Joan: Another Look upon Martin Le Franc's “Papesse Jeane” (c. 1440) and Dietrich Schernberg's Play “Frau Jutta” (1480) // Fifteenth-Century Studies. Stuttg., 2001. Vol. 26. P. 75-85;

- Rustici CM The Afterlife of Pope Joan: Deploying the Popess Legend in Early Modern England. Ann Arbor, 2006;

- Obenaus M. Hure und Heilige: Verhandlungen über die Päpstin zwischen spätem Mittelalter und früher Neuzeit. Hamburg, 2008;

- Kerner M., Herber K. Die Päpstin Johanna: Biographie einer Legende. Cologne; Weimar; W., 2010.

Gospel of John

| Bible Search** To search the Bible on your mobile device, click here |

Chapters: , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , ,

CHAPTER 12

1 Six days before the Passover Jesus came to Bethany, where Lazarus was dead, whom He raised from the dead. 2 There they prepared a supper for Him, and Martha served, and Lazarus was one of those who sat with Him. 3 And Mary took a pound of pure precious ointment, anointed the feet of Jesus, and wiped His feet with her hair; and the house was filled with the fragrance of the world. 4 Then one of His disciples, Judas Simon Iscariot, who wanted to betray Him, said: 5 Why not sell this ointment for three hundred denarii and give it to the poor? 6 He said this not because he cared about the poor, but because he was a thief. He had money with him

box and carried that they put it there.

7 And Jesus said, Leave her alone; She saved it for the day of My burial. 8 For you always have the poor with you, but not always Me. 9 Many of the Jews knew that He was there, and they came not only for Jesus, but also to see Lazarus, whom He had raised from the dead. 10 And the chief priests decided to kill Lazarus also, 11 because for his sake many of the Jews came and believed in Jesus. 12 The next day, the multitude of people who had come to the feast, hearing that Jesus was coming to Jerusalem, 13 took palm branches and came out to meet Him and exclaimed: Hosanna! Blessed is he who comes in the name of the Lord, the King of Israel! 14 Jesus found a colt and sat on it, as it is written: 15 Fear not, daughter of Zion! Behold, your King is coming, sitting on a colt. 16 His disciples did not understand this at first; but when Jesus became glorified, then they remembered that it was written about Him, and they did it to Him. 17 The people who were with Him before testified that He called Lazarus from the tomb and raised him from the dead. 18 Therefore the people met Him, for they heard that He had performed this miracle. 19 But the Pharisees said to each other, “Do you see that you are not getting anything done? the whole world follows Him. 20 Of those who came to worship at the feast, there were some Greeks. 21 They approached Philip, who was from Bethsaida in Galilee, and asked him, saying: Master! we want to see Jesus. 22 Philip goes and tells Andrew about this; and then Andrew and Philip tell Jesus about this. 23 Jesus answered and said to them, “The hour has come for the Son of Man to be glorified.” 24 Truly, truly, I say to you, unless a grain of wheat falls into the ground and dies, it remains alone; and if it dies, it will bear much fruit. 25 He who loves his life will destroy it; But he who hates his life in this world will keep it to eternal life. 26 Whoever serves Me, let him follow Me; and where I am, there will my servant also be. And whoever serves Me, My Father will honor him. 27 My soul is now troubled; and what should I say? Father! deliver Me from this hour! But for this hour I have come. 28 Father! glorify Your name. Then a voice came from heaven: I have glorified it and will glorify it again. 29 The people standing and hearing it

said, “This is thunder; and others said: The angel spoke to him. 30 Jesus answered this, “This voice was not for me, but for the people.” 31 Now is the judgment of this world; now the prince of this world will be cast out. 32 And when I am lifted up from the earth, I will draw everyone to Me. 33 These things He spoke, making it clear by what kind of death He would die. 34 The people answered him: We have heard from the law that Christ abides forever; How then do You say that the Son of Man must be lifted up? Who is this Son of Man? 35 Then Jesus said to them, “For a little while yet the light is with you; walk while there is light, lest darkness overtake you: but he who walks in darkness does not know where he is going. 36 As long as the light is with you, believe in the light, that you may be children of light. Having said this, Jesus walked away and hid from them. 37 He performed so many miracles before them, and they did not believe in Him, 38 so that the word of Isaiah the prophet might be fulfilled: Lord! who believed what they heard from us? and to whom was the arm of the Lord revealed? 39 Therefore they could not believe, because, as Isaiah also said, 40 this people have blinded their eyes and hardened their hearts, lest they see with their eyes, and understand with their hearts, and convert, that I might heal them. 41 These things said Isaiah, when he saw His glory and spoke of Him. 42 However, many of the rulers believed in Him; but for the sake of the Pharisees they did not confess, lest they should be put out of the synagogue, 43 for they loved the glory of men more than the glory of God. 44 Jesus cried out and said, “He who believes in Me does not believe in Me, but in Him who sent Me.” 45 And he who sees Me sees Him who sent Me. 46 I have come as light into the world, so that whoever believes in Me will not remain in darkness. 47 And if anyone hears My words and does not believe, I do not judge him, for I did not come to judge the world, but to save the world. 48 He who rejects Me and does not accept My words has one who judges him: the word that I have spoken will judge him at the last day. 49 For I spoke not of Myself; but the Father who sent Me, He gave Me a commandment, what to say and what to say. 50 And I know that His commandment is eternal life. So what I say, I say as the Father told me.

| All books of the Bible ✝ | Top ↑ | Next >> | |

| Tags: Read online, Gospel of MATTHEW, Mark, Luke, John, holy apostle, NEW Testament, BIBLE | |||

| * Yandex Search is not conducted in all chapters of the Bible, but only in those chapters (pages of this site) that are included in the Search by the Yandex robot | |||

GREGORY XII

Gregory XII, Pope of Rome. Engraving. 1600 (Sacchi. Vitis pontificum. 1626) (RSL)

Gregory XII, Pope of Rome. Engraving. 1600 (Sacchi. Vitis pontificum. 1626) (RSL) (c. 1325 or c. 1335, Venice - 10/18/1417, Recanati; before being elected pope - Angelo Corrario), Pope (Dec. 19, 1406 - July 4, 1415 ).

Genus. in a noble family. Having received a theological education, he was a canon of the Venetian Cathedral. In 1377 he received a master's degree in theology and became dean at Corona. With the beginning of the schism in the Catholic Church in Oct. 1380, Pope Urban VI, who was in Rome, appointed Bishop of Castello, then on February 21. 1387 - legate in Istria and Dalmatia. 1 Dec. 1390 Pope Boniface IX appointed him Lat. patriarch of the K-field. Since 1395, the administrator of the bishopric is Crown. From 1399 he served as papal legate to the Neapolitan cor. Vladislav. 4 Apr. 1405 Appointed legate of the March of Ancona by Pope Innocent VII. On June 12 of the same year, he was elevated to the dignity of Cardinal Presbyter of Rome. c. St. Mark with the retention of the department of lat. K-Polish Patriarch. After the death of Pope Innocent VII (Nov. 6, 1406), at a conclave in Rome, 19 cardinals elected Angelo Corrario as the new pope, who took the name Gregory XII. G.'s coronation and enthronement took place on December 19. 1406

During the pontificate of G., schism became Catholic. The church has become tense. On the one hand, the French cor. Charles VI, who supported the Avignon antipope Benedict XIII, as well as the University of Paris called on the cardinals in Rome to refrain from electing a pope and to enter into negotiations with Avignon. On the other hand, Rome was threatened by the Kingdom of Naples, because cor. Vladislav feared that the Papal throne would be occupied by a protege of France, which would lead to the strengthening of the position of Louis II of Anjou, a relative of the French, who was laying claim to the Neapolitan throne. king. Even before the conclave began, all the cardinals gathered in Rome signed an oath expressing their readiness, if elected, to renounce the Papal throne in order to overcome the schism if Benedict XIII, who was in Avignon, did the same at the same time.

Germany was recognized as the legitimate Pope of Rome by the Roman-German Empire, England, Hungary, Bohemia, Poland, the Scandinavian countries, the Florentine and Venetian republics, and the Kingdom of Naples. On Dec. 1406 G. sent Benedict XIII a message about his election and notification of the oath taken. In a reply letter (Jan. 1407), Benedict XIII proposed organizing a meeting between them to discuss overcoming the schism. From 3 to 21 April In 1407, negotiations were held in Marseilles about a meeting between G. and Benedict XIII, at which it was agreed that it would take place no later than November 1. 1407 in Savona, which was in the sphere of the French. influence. Aug 9 G. left Rome for Viterbo, on September 4th. to 22 Jan. 1408 was in Siena, 28 Jan. arrived in Lucca. G. suggested that the antipope change the meeting place, because at the request of Benedict XIII, who had been in Savona since September 24. 1407, the French were drawn to it. troops. At the same time, G.’s inner circle, as well as the Neapolitan correspondent. Vladislav, representatives from Venice and Hungary insisted on refusing negotiations with Benedict XIII.

In April 1408, under the pretext of unrest that began in Rome, cor. Vladislav brought troops into the Papal States. Finding yourself dependent on the core. Vladislav, May 4, 1408 G. forbade the cardinals to enter into negotiations with the French who supported Benedict XIII. On the same day, he announced the elevation of 4 people to the rank of cardinal. from his inner circle, two of whom were his nephews: Antonio Corrario and Gabriele Condolmieri (later Pope Eugene IV). The appointment of new cardinals violated the terms of G.'s oath before the conclave and displeased Benedict XIII, who had not appointed cardinals since 1397. On May 9, 1408, he elevated 2 people to the rank of cardinal. Franz. the king, however, threatened to withdraw his support from Benedict XIII if the planned meeting did not take place. Meanwhile, G.’s actual refusal to negotiate with the antipope and the violation of the oath he had taken caused a split in his circle. May 11 card. Jean Gilles refused to obey G. and fled from Lucca to Pisa; he was followed by 6 more cardinals. On July 31, these cardinals and some of the Avignon cardinals who joined them decided to seek the abdication of both G. and Benedict XIII and convene a Council in Pisa to elect a new pope.

At the Council of Pisa (March 25 - Aug. 27, 1409), the cardinals invited both opposing popes, but neither of them showed up. The interests of G. at the Council were defended by the influential prince. Charles Malatesta, who failed to win over the participants of the Council to the side of Greece. On June 5, 1409, at the 15th session of the Council, Greece and Benedict XIII were deposed (this date was considered the end of the pontificate of Greece until the 50s of the XX century. ). At the 19th session of the Council (June 26, 1409), Peter Philargus was elected as the new pope, who took the name Alexander V, who was recognized by France, England, Florence, Venice and a number of Germany. principalities

Simultaneously with the Council of Pisa, Benedict XIII convened a Council in Perpignan. June 6, 1409 G. with the support of the Germans. cor. Ruprecht III opened the Council of Cividale del Friuli, at which Alexander V and Benedict XIII were declared schismatics. Despite the presence of representatives of Ruprecht III and the King of Naples, G. feared threats from the Patriarch of Aquileia and at the end of the Council (September 5, 1409) secretly left Cividale del Friuli, making a statement about his readiness to renounce the papacy if his 2 did the same opponent. On Nov. In 1409 he arrived in Gaeta, where he found himself almost completely subjugated by the cor. Vladislav. In 1410, G. sent the Bishop of Riga. John on a mission to the Northern countries. Europe in order to persuade them to recognize him as the legitimate pope. In 1411 he issued the bull “In coena Domini”, which confirmed the excommunication of Louis II of Anjou, Benedict XIII and Balthasar Cossa (see John XXIII, antipope; elected on May 25, 1410 in place of the deceased Alexander V).

With the loss of G. of almost all influence (by this time he was recognized as pope only by the Hungarian king and the German cor. Ruprecht III), the Neapolitan cor. Vladislav stopped providing him with services. support and in May 1412 recognized John XXIII as legitimate pope; in the same year, John XXIII was also recognized by the successor of Ruprecht III, Germany. cor. Sigismund I of Luxembourg. Oct 30 1412 G. was forced to leave Gaeta and go to Rimini to his ally Karl Malatesta.

9 Dec. 1413 John XXIII issued a bull convening a Council to finally end the schism. In March 1415, G. decided to renounce the papacy before the opening in November. 1414 by the Council of Constance. Considering, however, the Council to be deprived of legitimacy (since the bull on its convocation was issued by the illegitimate Pope John XXIII), G. sent his representatives to Constance, and at the 14th session (July 4, 1415) card. Giovanni Dominici announced G.'s decision to convene the Council of Constance, which, from the point of view. supporters of G., gave the Council the status of legal. Then another representative of the pope, Karl Malatesta, read out G.'s decision to abdicate the Papal throne. Both of G.'s rivals, Benedict XIII and John XXIII, were deprived of papal power by the decision of the Council. Because G.’s renunciation helped to end the schism in Catholicism. Church, the Council of Constance granted him the title of cardinal bishop of Porto and Santa Rufina, the position of life legate in the Ancona March and dean of the college of cardinals with the honorary right to occupy 2nd place after the pope in all officialdom. ceremonies

On July 19, 1415, while in the castle of Montefiore, G. received news of the announcement of his abdication and the decision of the Council regarding his future fate. On July 20, G. held his last consistory, laid aside the signs of papal power and donned the robes of a cardinal. After this, the cardinals around him went to the Council of Constance, and he moved in January. 1416 in Recanati, where he died and was buried in the cathedral.

Source: Lettres de Grégoire XII (1406-1415): Textes et analyzes / Ed. M. Soenen. Brux.; R., 1976.

Lit.: Raffaelli F. Il monumento di papa Grigorio XII ed i suoi donativi alla cattedrale basilica di Recanati. Fermo, 1877; Erler G. Florenz, Neapel und das papstliche Schisma // Hist. Taschenbuch. 1889. Bd. 8. S. 179-230; Finke H. Eine Papstcronik des XV. Jh. // RQS. 1890. Bd. 4. S. 340-362; Meister A. Das Konzil zu Cividale 1409 // Hist. Jb. 1893. Bd. 14. S. 320-330; Schlitz L. Die Quellen zur Geschichte des Konzils von Cividale 1409 // RQS. 1894. Bd. 8. S. 217-259; Eubel K. Das Itinerar der Päpste zur Zeit des grossen Schisma // Hist. Jb. 1895. Bd. 16. S. 545-564; idem. Die "Provisiones Praelatorum" durch Gregor XII. nach Mitte Mai 1408 // RQS. 1896. Bd. 10. S. 99-131; Lisini A. Papa Gregorio XII ei Senesi // La Rassegna Nazionale Firenze. 1896. Vol. 91. P. 97-117, 280-321; Piva E. Venezia i lo scisma durante il pontificato di Gregorio XII (1406-1409) // Nuovo Archivio Veneto. 1897. Vol. 13. P. 135-158; Salembier L. Le Grand schisme d'Occident. P., 1900; Zanutto L. Itinerario del pontefice Gregorio XII da Roma (9 ag. 1407) a Cividale del Friuli (26 mag. 1409): Studio storico. Udine, 1901; Valois N. La France et le Grand Schisme d'Occident. P., 1901-1902. Vol. 3-4; Hollerbach J. Die Gregorianische Partei, Sigismund und das Konstanzer Konzil // RQS. 1909. Bd. 23. H. 2. S. 129-164; 1910. Bd. 24. H. 2. S. 3-39, 121-140; Montor A., de. The Lives and Times of the Popes. NY, 1911. P. 97-108; Tihon C. Les expectatives in forma pauperum de Grégoire XII // Bull. de l'Inst. hist. Belge de Rome. 1926. Vol. 6. P. 71-101; An. Pont. Cath. 1931. P. 127, 139, 141, 164-165, 168; Petersohn J. Papst Gregors XII.: Flucht aus Cividale (1409) und die Sicherstellung des papstlichen Paramentschatzes // RQS. 1963. Bd. 58. S. 51-70; Girgensohn D. Kardinal Antonio Caetani und Gregor XII. in den Jahren 1406-1408 // QFIAB. 1984. Bd. 64. S. 116-226; Soenen M. Grégoire XII // Dictionnaire hist. de la Papauté/Dir. Ph. Levillain. P., 1994. P. 758-760.

A. G. Krysov