All people around the world can read the Bible in whole or in part in their native language.

— We Orthodox Christians are often reproached for not reading the Bible as often as, for example, Protestants do. How fair are such accusations?

- The Orthodox Church recognizes two sources of knowledge of God - Holy Scripture and Holy Tradition. Moreover, the first is an integral part of the second. After all, initially the sermons of the holy apostles were delivered and transmitted orally. Sacred Tradition includes not only Holy Scripture, but also liturgical texts, decrees of Ecumenical Councils, iconography and a number of other sources that occupy an important place in the life of the Church. And everything that is said in the Holy Scriptures is also in the Tradition of the Church.

Since ancient times, the life of a Christian has been inextricably linked with biblical texts. And in the 16th century, when the so-called “Reformation” arose, the situation changed. Protestants abandoned the Holy Tradition of the Church and limited themselves to only studying the Holy Scriptures. And therefore, a special kind of piety appeared among them - reading and studying biblical texts. Once again I want to emphasize: from the point of view of the Orthodox Church, Holy Tradition includes the entire scope of church life, including the Holy Scriptures. Moreover, even if someone does not read the Word of God, but regularly attends the temple, he hears that the entire service is permeated with biblical quotations. Thus, if a person lives a church life, then he is in the atmosphere of the Bible.

The main thing is to have a sincere desire to know the Word of God

— How to study the Bible correctly? Is it worth starting knowledge from the first pages of Genesis?

— The main thing is to have a sincere desire to learn the Word of God. It's better to start with the New Testament. Experienced pastors recommend getting acquainted with the Bible through the Gospel of Mark (that is, not in the order in which they are presented). It is the shortest, written in simple and accessible language. Having read the Gospels of Matthew, Luke and John, we move on to the book of Acts, the Apostolic Epistles and the Apocalypse (the most complex and most mysterious book in the entire Bible). And only after this can you begin to read the Old Testament books. Only after reading the New Testament, it is easier to understand the meaning of the Old. After all, it was not for nothing that the Apostle Paul said that the Old Testament legislation was a teacher to Christ (see: Gal. 3: 24): it leads a person, as if a child by the hand, to let him truly understand what happened during the Incarnation, What in principle is the incarnation of God for a person...

The New Testament - A Guide to Living with Christ

With the birth of the Savior, a new era in the history of mankind begins. The New Testament describes the main stages of Christ's stay on earth:

- conception;

- birth;

- life;

- miracles;

- death;

- resurrection;

- Ascension.

Jesus Christ is the heart of the entire Bible. There is no other way to gain eternal life except by faith in the Savior, for Jesus Himself called Himself the Way, the Truth and the Life (John 14).

Each of the twelve apostles left a message to the world. Only four Gospels included in the New Testament are recognized as inspired and canonical.

Twelve disciples of Jesus Christ

The New Testament begins with the Gospels, the Good News conveyed through ordinary people who later became apostles. The Sermon on the Mount, known to all Christians, teaches believers how to become blessed in order to acquire the kingdom of God already on earth.

Only John was among the disciples who were constantly near the Teacher. Luke at one time healed people; all the information conveyed to him was collected during the time of Paul, after the crucifixion of the Savior. This message reflects the researcher's approach to historical events. Matthew was chosen as one of the 12 apostles instead of the traitor Judas Iscariot.

Important! Epistles that are not included in the New Testament due to doubts about their authenticity are called apocryphal. The most famous of them are the Gospels of Judas, Thomas, Mary Magdalene and others.

In the “Acts of the Holy Apostles,” transmitted by the Apostle Paul, who never saw Jesus the man, but who was given the grace to hear and see the bright Light of the Son of God, the life of Christians after the resurrection of Christ is described. The teaching books of the New Testament contain the messages of the apostles to specific people and entire churches.

By studying the Word of God, transmitted by His disciples, Orthodox people see before themselves an example to follow, to be transformed into the image of the Savior. Paul's first letter to the Corinthians contains a hymn of love (1 Cor. 13:4-8), reading each point of which you truly begin to understand what God's love is.

In Galatians 5:19-23, the Apostle Paul offers a test by which every Orthodox believer can determine whether he is walking according to the flesh or according to the spirit.

The Apostle James showed the power of the word and the unbridled tongue through which both blessing and curse flow.

The New Testament ends with the book of Revelations of the Apostle John, the only one of all twelve disciples of Jesus who died a natural death. At the age of 80, for his worship of Christ, John was created on the island of Patmos for hard work, from where he was transferred to heaven to receive Revelation for humanity.

Attention! Revelation is the most difficult book to understand, its messages are revealed to selected Christians who have a personal relationship with the Holy Trinity.

Revelation of Saint John the Theologian

It is important to understand that reading the Holy Scriptures is part of the spiritual achievement

— What if the reader does not understand some episodes of the Bible? What to do in this case? Who should I contact?

— It is advisable to have books on hand that explain the Holy Scriptures. We can recommend the works of Blessed Theophylact of Bulgaria. His explanations are short, but very accessible and deeply ecclesiastical, reflecting the Tradition of the Church. The conversations of St. John Chrysostom on the Gospels and Apostolic Epistles are also classic. If any questions arise, it would be a good idea to consult with an experienced priest. It is necessary to understand that reading the Holy Scriptures is part of a spiritual achievement. And it is very important to pray, to cleanse your soul. Indeed, even in the Old Testament it was said: wisdom will not enter an evil soul and will not dwell in a body enslaved to sin, for the Holy Spirit of wisdom will withdraw from wickedness and turn away from foolish speculations, and will be ashamed of the approaching unrighteousness (Wisdom 1: 4-5) .

Biblical canon

The Bible consists of 66 books; 39 are found in the Old Testament and 27 in the New. The books of the Old Testament are artificially counted as 22, according to the number of letters of the Hebrew alphabet, or as 24, according to the number of letters of the Greek alphabet (for this reason, some of the books are combined).

In addition, the Old Testament includes 11 so-called deuterocanonical books (see), which the Church does not equate with canonical books, but recognizes as edifying and useful.

The composition of the books of the Bible (Biblical Canon) developed gradually. The books of the Old Testament were created over a significant period of time: from the 13th century. BC e. until the 4th century BC e. It is believed that the canonical books of the Old Testament were collected together by the scribe Ezra, who lived approximately 450 BC. e.

The canon of the books of the Old Testament was finally approved at the Council of Laodicea in 364 and the Council of Carthage in 397; in fact, the Church has used the Old Testament canon in its present form since ancient times. Yes, St. Melito of Sardis, in a Letter to Anesimius, dating from about 170, already gives a list of books of the Old Testament that almost completely coincides with that approved in the 4th century.

In general terms, the canon of the New Testament had already been formed by the middle of the 2nd century, as evidenced by the citation of the New Testament Scriptures by the apostolic men and apologists of the 2nd century, for example, schmch. Irenaeus of Lyons.

Both Testaments were first brought into canonical form at local councils in the 4th century: the Council of Hippo in 393 and the Council of Carthage in 397.

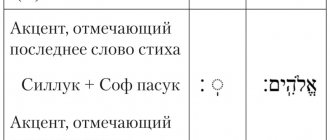

The division of words in the Bible was introduced in the century by the deacon of the Alexandrian Church Eulalis. The modern division into chapters dates back to Cardinal Stephen Langton, who divided the Latin translation of the Bible, the Vulgate, in 1205. In 1551, the Genevan printer Robert Stephen introduced the modern division of chapters into verses.

Before studying the Holy Scriptures, you need to familiarize yourself with the works of the holy fathers

- So, you need to prepare for reading the Holy Scriptures in a special way?

— Experienced elders in monasteries gave the novice a rule: before studying the Holy Scriptures, you first need to familiarize yourself with the works of the holy fathers. Bible readings are not just studying the Word of God, they are like prayer. In general, I would recommend reading the Bible in the morning, after the prayer rule. I think it’s easy to set aside 15–20 minutes to read one or two chapters from the Gospel, the Apostolic Epistles. This way you can get a spiritual charge for the whole day. Very often, in this way, answers to serious questions that life poses to a person appear.

Ostromir Gospel (1056 - 1057)

About Sacred Tradition

Speaking about the Holy Scriptures, we should not forget about another way of disseminating divine revelation - Holy Tradition. It was through him that the doctrine of faith was transmitted in ancient times. This method of transmission exists to this day, for under Sacred Tradition is conceived the transmission not only of teaching, but also of sacraments, sacred rites, and the Law of God from ancestors who correctly worship God to the same descendants.

In the twentieth century, there was some change in the balance of views on the role of these sources of divine revelation. In this regard, Elder Silouan says that Tradition covers the entire life of the church. Therefore, that very Holy Scripture is one of its forms. The meaning of each of the sources is not contrasted here, but the special role of Tradition is only emphasized.

The main tenets of Scripture are the voice of God, sounding in the nature of each of us

— Sometimes the following situation happens: you read it, understand what it’s about, but it doesn’t suit you because you don’t agree with what’s written...

— According to Tertullian (one of the church writers of antiquity), our soul is Christian by nature. Thus, biblical truths were given to man from the very beginning; they are embedded in his nature, his consciousness. We sometimes call this conscience, that is, it is not something new that is unusual for human nature. The main tenets of the Holy Scriptures are the voice of God, sounding in the nature of each of us. Therefore, you need, first of all, to pay attention to your life: is everything in it consistent with the commandments of God? If a person does not want to listen to the voice of God, then what other voice does he need? Who will he listen to?

Buddhist Tripitaka

It is a collection of sacred texts that were written down after Shakyamuni Buddha died. The name is noteworthy, which is translated as “three baskets of wisdom.” It corresponds to the division of sacred texts into three chapters.

The first is the Vinaya Pitaka. Here are texts that contain rules governing life in the monastic community of the Sangha. In addition to the edifying aspects, there is also a story about the history of the origin of these norms.

The second, the Sutra Pitaka, contains stories about the life of the Buddha, written down by him personally and sometimes by his followers.

The third - Abhidharma Pitaka - includes the philosophical paradigm of teaching. Here is a systematic presentation of it, based on in-depth scientific analysis. While the first two chapters provide practical insights into how to achieve a state of enlightenment, the third strengthens the theoretical foundation of Buddhism.

The Buddhist religion contains a considerable number of versions of this creed. The most famous of them is the Pali Canon.

The main difference between the Bible and other books is revelation

— Saint Philaret was once asked: how can one believe that the prophet Jonah was swallowed by a whale with a very narrow throat? In response, he said: “If it were written in the Holy Scriptures that it was not a whale that swallowed Jonah, but Jonah a whale, I would believe that too.” Of course, today such statements can be perceived with sarcasm. In this regard, the question arises: why does the Church trust the Holy Scripture so much? After all, the biblical books were written by people...

— The main difference between the Bible and other books is revelation. This is not just the work of some outstanding person. Through the prophets and apostles, the voice of God Himself is reproduced in accessible language. If the Creator addresses us, then how should we react to this? Hence such attention and such trust in the Holy Scriptures.

— In what language were the biblical books written? How has their translation affected the modern perception of sacred texts?

— Most of the Old Testament books are written in Hebrew. Some of them survive only in Aramaic. The already mentioned non-canonical books have reached us exclusively in Greek: for example, Judith, Tobit, Baruch and the Maccabees. The third book of Ezra is known to us in its entirety only in Latin. As for the New Testament, it was mainly written in Greek - in the Koine dialect. Some biblical scholars believe that the Gospel of Matthew was written in Hebrew, but no primary sources have reached us (there are only translations). Of course, it would be better to read and study biblical books based on primary sources and originals. But this has been the case since ancient times: all books of Holy Scripture were translated. And therefore, for the most part, people are familiar with the Holy Scriptures translated into their native language.

Russian Orthodox Church

On December 19, 2014, at the Veliko Tarnovo University named after Saints Cyril and Methodius (Bulgaria), a solemn ceremony was held to present the honorary degree of doctor honoris causa of this university to the chairman of the Department for External Church Relations of the Moscow Patriarchate, chairman of the Synodal Biblical-Theological Commission, Metropolitan Hilarion of Volokolamsk. Vladyka Hilarion gave an official speech.

1. Scripture and Tradition

Christianity is a revealed religion. In the Orthodox understanding, Divine Revelation includes Holy Scripture and Holy Tradition. Scripture is the entire Bible, that is, all the books of the Old and New Testaments. As for Tradition, this term requires special clarification, since it is used in different meanings. Tradition is often understood as the entire set of written and oral sources with the help of which the Christian faith is passed on from generation to generation. The Apostle Paul says: “Stand fast and hold to the traditions which you were taught either by our word or by our epistle” (2 Thess. 2:15). By “word” here we mean oral Tradition, by “message” - written. Saint Basil the Great included the sign of the cross, turning in prayer to the east, the epiclesis of the Eucharist, the rite of consecration of the water of baptism and the oil of anointing, the threefold immersion of a person at baptism, etc., to the oral Tradition, that is, predominantly liturgical or ritual traditions transmitted orally and firmly entered into church practice. Subsequently, these customs were recorded in writing - in the works of the Fathers of the Church, in the decrees of the Ecumenical and Local Councils, in liturgical texts. A significant part of what was originally oral Tradition became written Tradition, which continued to coexist with oral Tradition.

If Tradition is understood in the sense of the totality of oral and written sources, then how does it relate to Scripture? Is Scripture something external to Tradition, or is it an integral part of Tradition?

Before answering this question, it should be noted that the problem of the relationship between Scripture and Tradition, although reflected in many Orthodox authors, is not Orthodox in origin. The question of what is more important, Scripture or Tradition, was raised during the controversy between the Reformation and Counter-Reformation in the 16th-17th centuries. The leaders of the Reformation (Luther, Calvin) put forward the principle of “the sufficiency of Scripture,” according to which only Scripture enjoys absolute authority in the Church; As for later doctrinal documents, be they decrees of Councils or the works of the Fathers of the Church, they are authoritative only insofar as they are consistent with the teaching of Scripture. Those dogmatic definitions, liturgical and ritual traditions that were not based on the authority of Scripture could not, according to the leaders of the Reformation, be recognized as legitimate and therefore were subject to abolition. With the Reformation, the process of revision of Church Tradition began, which continues in the depths of Protestantism to this day.

In contrast to the Protestant principle of “sola Scriptura” (Latin for “Scripture alone”), Counter-Reformation theologians emphasized the importance of Tradition, without which, in their opinion, Scripture would have no authority. Luther's opponent at the Leipzig Disputation of 1519 argued that "Scripture is not authentic without the authority of the Church." Opponents of the Reformation pointed out, in particular, that the canon of Holy Scripture was formed precisely by Church Tradition, which determined which books should be included in it and which should not. At the Council of Trent in 1546, the theory of two sources was formulated, according to which Scripture cannot be considered as the only source of Divine Revelation: an equally important source is Tradition, which constitutes a vital addition to Scripture.

Russian Orthodox theologians of the 19th century, speaking about Scripture and Tradition, placed emphasis somewhat differently. They insisted on the primacy of Tradition in relation to Scripture and traced the beginning of Christian Tradition not only to the New Testament Church, but also to the times of the Old Testament. Saint Philaret of Moscow emphasized that the Holy Scripture of the Old Testament began with Moses, but before Moses, the true faith was preserved and spread through Tradition. As for the Holy Scripture of the New Testament, it began with the Evangelist Matthew, but before that “the foundation of dogmas, the teaching of life, the rules of worship, the laws of church government” were in Tradition.

At A.S. Khomyakov, the relationship between Tradition and Scripture is considered in the context of the teaching about the action of the Holy Spirit in the Church. Khomyakov believed that Scripture is preceded by Tradition, and Tradition is preceded by “deed,” by which he understood revealed religion, starting from Adam, Noah, Abraham and other “ancestors and representatives of the Old Testament Church.” The Church of Christ is a continuation of the Old Testament Church: the Spirit of God lived and continues to live in both. This Spirit acts in the Church in a variety of ways - in Scripture, Tradition and in practice. The unity of Scripture and Tradition is comprehended by a person who lives in the Church; Outside the Church it is impossible to comprehend either Scripture, Tradition, or deeds.

In the 20th century, Khomyakov’s thoughts about Tradition were developed by V.N. Lossky. He defined Tradition as “the life of the Holy Spirit in the Church, the life that imparts to each member of the Body of Christ the ability to hear, accept, and know the Truth in its inherent light, and not in the natural light of the human mind.” According to Lossky, life in Tradition is a condition for the correct perception of Scripture, it is nothing more than knowledge of God, communication with God and vision of God, which were inherent in Adam before his expulsion from paradise, the biblical forefathers Abraham, Isaac and Jacob, the seer Moses and the prophets, and then “ eyewitnesses and ministers of the Word" (Luke 1:2) - the apostles and followers of Christ. The unity and continuity of this experience, preserved in the Church right up to the present time, constitutes the essence of Church Tradition. A person outside the Church, even if he studied all the sources of Christian doctrine, will not be able to see its inner core.

Answering the question posed earlier about whether Scripture is something external to Tradition or an integral part of the latter, we must say with all certainty that in the Orthodox understanding Scripture is part of Tradition and is unthinkable outside of Tradition. Therefore, Scripture is by no means self-sufficient and cannot by itself, isolated from church tradition, serve as a criterion of Truth. The books of Holy Scripture were created at different times by different authors, and each of these books reflected the experience of a particular person or group of people, reflecting a certain historical stage in the life of the Church, including the Old Testament period). The primary was experience, and the secondary was its expression in the books of Scripture. It is the Church that gives these books - both the Old and the New Testaments - the unity that they lack when viewed from a purely historical or textual point of view.

The Church considers Scripture to be “inspired by God” (2 Tim. 3:16), not because the books included in it were written by God, but because the Spirit of God inspired their authors, revealed the Truth to them, and held together their scattered writings into a single whole. But in the action of the Holy Spirit there is no violence over the mind, heart and will of man; on the contrary, the Holy Spirit helped man to mobilize his own inner resources to comprehend the key truths of the Christian Revelation. The creative process, the result of which was the creation of a particular book of Holy Scripture, can be represented as a synergy, joint action, collaboration between man and God: a person describes certain events or sets out various aspects of a teaching, and God helps him to understand and adequately express them. The books of Holy Scripture were written by people who were not in a state of trance, but in sober memory, and each of the books bears the imprint of the creative individuality of the author.

Fidelity to Tradition and life in the Holy Spirit helped the Church to recognize the internal unity of the Old Testament and New Testament books, created by different authors at different times, and from all the diversity of ancient written monuments to select into the canon of Holy Scripture those books that are bound by this unity, to separate divinely inspired works from non-inspired ones. inspired.

2. Holy Scripture in the Orthodox Church

In the Orthodox tradition, the Old Testament, the Gospel and the corpus of the Apostolic Epistles are perceived as three parts of an indivisible whole. At the same time, the Gospel is given unconditional preference as a source that brings the living voice of Jesus to Christians, the Old Testament is perceived as prefiguring Christian truths, and the Apostolic Epistles are perceived as an authoritative interpretation of the Gospel belonging to Christ’s closest disciples. In accordance with this understanding, the Hieromartyr Ignatius the God-Bearer in his letter to the Philadelphians says: “Let us resort to the Gospel as to the flesh of Jesus, and to the apostles as to the presbytery of the Church. Let us also love the prophets, for they also proclaimed what pertains to the Gospel, they trusted in Christ and looked for Him and were saved by faith in Him.”

The doctrine of the Gospel as “the flesh of Jesus,” His incarnation in the word, was developed by Origen. Throughout Scripture he sees the “kenosis” (exhaustion) of God the Word incarnating himself in the imperfect forms of human words: “Everything that is recognized as the word of God is the revelation of the Word of God made flesh, which was with God in the beginning (John 1:2) and exhausted Himself.” . Therefore, we recognize the Word of God made man as something human, for the Word in the Scriptures always becomes flesh and dwells among us (John 1:14).”

This explains the fact that in Orthodox worship the Gospel is not only a book to read, but also an object of liturgical worship: the closed Gospel lies on the throne, it is kissed, it is taken out for worship by the faithful. During the episcopal consecration, the revealed Gospel is placed on the head of the person being ordained, and during the sacrament of the Blessing of Unction, the revealed Gospel is placed on the head of the sick person. As an object of liturgical worship, the Gospel is perceived as a symbol of Christ Himself.

In the Orthodox Church, the Gospel is read daily during worship. For liturgical reading, it is divided not into chapters, but into “conceptions.” The four Gospels are read in their entirety in the Church throughout the year, and for each day of the church year there is a specific Gospel beginning, which the believers listen to while standing. On Good Friday, when the Church remembers the suffering and death of the Savior on the cross, a special service is held with the reading of twelve Gospel passages about the passion of Christ. The annual cycle of Gospel readings begins on the night of Holy Easter, when the prologue of the Gospel of John is read. After the Gospel of John, which is read during the Easter period, the readings of the Gospels of Matthew, Mark and Luke begin.

The Acts of the Apostles, conciliar epistles and the epistles of the Apostle Paul are also read in the Church every day and are also read in their entirety throughout the year. The reading of the Acts begins on the night of Holy Easter and continues throughout the Easter period, followed by the conciliar epistles and the epistles of the Apostle Paul.

As for the books of the Old Testament, they are read selectively in the Church. The basis of Orthodox worship is the Psalter, which is read in its entirety throughout the week, and twice a week during Lent. During Lent, conceptions from the Books of Genesis and Exodus, the Book of the Prophet Isaiah, and the Book of the Wisdom of Solomon are read daily. On holidays and days of remembrance of especially revered saints, it is necessary to read three “proverbs” - three passages from the books of the Old Testament. On the eve of the great holidays - on the eve of Christmas, Epiphany and Easter - special services are held with the reading of a larger number of proverbs (up to fifteen), representing a thematic selection from the entire Old Testament relating to the celebrated event.

In the Christian tradition, the Old Testament is perceived as a prototype of New Testament realities and is viewed through the prism of the New Testament. This kind of interpretation is called “typological” in science. It began with Christ Himself, who said about the Old Testament: “Search the Scriptures, for through them you think you have eternal life; and they testify of Me” (John 5:39). In accordance with this instruction of Christ, in the Gospels many events from His life are interpreted as the fulfillment of Old Testament prophecies. Typological interpretations of the Old Testament are found in the epistles of the Apostle Paul, especially in the Epistle to the Hebrews, where the entire Old Testament history is interpreted in a representative, typological sense. The same tradition is continued in the liturgical texts of the Orthodox Church, filled with allusions to events from the Old Testament, which are interpreted in relation to Christ and the events from His life, as well as to events from the life of the New Testament Church.

According to the teachings of Gregory the Theologian, the Holy Scriptures contain all the dogmatic truths of the Christian Church: you just need to be able to recognize them. Nazianzen proposes a method of reading Scripture that can be called “retrospective”: it consists in considering the texts of Scripture based on the subsequent Tradition of the Church, and identifying in them those dogmas that were more fully formulated in a later era. This approach to Scripture is fundamental in the patristic period. In particular, according to Gregory, not only the New Testament, but also the Old Testament texts contain the doctrine of the Holy Trinity.

Thus, the Bible must be read in the light of the dogmatic tradition of the Church. In the 4th century, both Orthodox and Arians resorted to the texts of Scripture to confirm their theological positions. Depending on these settings, different criteria were applied to the same texts and interpreted differently. For Gregory the Theologian, as for other Church Fathers, in particular Irenaeus of Lyons, there is one criterion for the correct approach to Scripture: fidelity to the Tradition of the Church. Only that interpretation of biblical texts is legitimate, Gregory believes, which is based on Church Tradition: any other interpretation is false, since it “robs” the Divine. Outside the context of Tradition, biblical texts lose their dogmatic significance. And vice versa, within Tradition, even those texts that do not directly express dogmatic truths receive new understanding. Christians see in the texts of Scripture what non-Christians do not see; to the Orthodox is revealed what remains hidden from heretics. The mystery of the Trinity for those outside the Church remains under a veil, which is removed only by Christ and only for those who are inside the Church.

If the Old Testament is a prototype of the New Testament, then the New Testament, according to some interpreters, is the shadow of the coming Kingdom of God: “The Law is the shadow of the Gospel, and the Gospel is the image of future blessings,” says Maximus the Confessor. The Monk Maximus borrowed this idea from Origen, as well as the allegorical method of interpreting Scripture, which he widely used. The allegorical method made it possible for Origen and other representatives of the Alexandrian school to consider stories from the Old and New Testaments as prototypes of the spiritual experience of an individual human personality. One of the classic examples of a mystical interpretation of this kind is Origen’s interpretation of the Song of Songs, where the reader goes far beyond the literal meaning and is transported to another reality, and the text itself is perceived only as an image, a symbol of this reality.

After Origen, this type of interpretation became widespread in the Orthodox tradition: we find it, in particular, in Gregory of Nyssa, Macarius of Egypt and Maximus the Confessor. Maximus the Confessor spoke of the interpretation of Holy Scripture as an ascent from the letter to the spirit. The anagogical method of interpreting Scripture (from the Greek anagogê, ascent), like the allegorical method, proceeds from the fact that the mystery of the biblical text is inexhaustible: only the outer outline of Scripture is limited by the framework of the narrative, and “contemplation” (theôria), or the mysterious inner meaning, is limitless. Everything in Scripture is connected with the inner spiritual life of man, and the letter of Scripture leads to this spiritual meaning.

Typological, allegorical and anagogical interpretation of Scripture also fills the liturgical texts of the Orthodox Church. For example, the Great Canon of St. Andrew of Crete, read during Lent, contains a whole gallery of biblical characters from the Old and New Testaments; in each case, the example of a biblical hero is accompanied by a commentary with reference to the spiritual experience of the person praying or a call to repentance. In this interpretation, the biblical character becomes a prototype of every believer.

If we talk about the Orthodox monastic tradition of interpreting the Holy Scriptures, then first of all it should be noted that the monks had a special attitude towards the Holy Scriptures as a source of religious inspiration: they not only read and interpreted it, but also memorized it. Monks, as a rule, were not interested in the “scientific” exegesis of Scripture: they viewed Scripture as a guide to practical activity and sought to understand it through the implementation of what was written in it. In their writings, the ascetic Holy Fathers insist that everything said in Scripture must be applied to one’s own life: then the hidden meaning of Scripture will become clear.

In the ascetic tradition of the Eastern Church there is the idea that reading the Holy Scriptures is only an auxiliary means on the path of the spiritual life of the ascetic. The statement of the Monk Isaac the Syrian is characteristic: “Until a person accepts the Comforter, he needs the Divine Scriptures... But when the power of the Spirit descends into the spiritual power operating in a person, then instead of the law of the Scriptures, the commandments of the Spirit take root in the heart...” According to the thought of St. Simeon the New Theologian, the need for Scripture disappears when a person meets God face to face.

The above judgments of the Fathers of the Eastern Church by no means deny the need to read the Holy Scriptures and do not diminish the significance of Scripture. Rather, it expresses the traditional Eastern Christian view that the experience of Christ in the Holy Spirit is superior to any verbal expression of this experience, whether in the Holy Scriptures or any other authoritative written source. Christianity is a religion of encountering God, not of bookish knowledge of God, and Christians are by no means “people of the Book,” as they are called in the Koran. Hieromartyr Hilarion (Troitsky) considers it no coincidence that Jesus Christ did not write a single book: the essence of Christianity is not in moral commandments, not in theological teaching, but in the salvation of man by the grace of the Holy Spirit in the Church founded by Christ.

Insisting on the priority of church experience, Orthodoxy rejects those interpretations of Holy Scripture that are not based on the experience of the Church, contradict this experience, or are the fruit of the activity of an autonomous human mind. This is the fundamental difference between Orthodoxy and Protestantism. By proclaiming the principle of “sola Scriptura” and rejecting the Tradition of the Church, Protestants opened up wide scope for arbitrary interpretations of the Holy Scriptures. Orthodoxy claims that outside the Church, outside Tradition, a correct understanding of Scripture is impossible.

3. Composition and authority of Tradition. Patristic heritage

In addition to the Holy Scriptures of the Old and New Testaments, the Tradition of the Orthodox Church includes other written sources, including liturgical texts, orders of the sacraments, decrees of the Ecumenical and Local Councils, the works of the Fathers and teachers of the ancient Church. What is the authority of these texts for an Orthodox Christian?

The doctrinal definitions of the Ecumenical Councils, which have undergone church reception, enjoy unconditional and indisputable authority. First of all, we are talking about the Nicene-Constantinopolitan Creed, which is a summary statement of Orthodox doctrine adopted at the First Ecumenical Council (325) and supplemented at the Second Council (381). We are also talking about other dogmatic definitions of the Councils included in the canonical collections of the Orthodox Church. These definitions are not subject to change and are generally binding for all members of the Church. As for the disciplinary rules of the Orthodox Church, their application is determined by the real life of the Church at each historical stage of its development. Some rules established by the Fathers of antiquity are preserved in the Orthodox Church, while others have fallen into disuse. The new codification of canon law is one of the urgent tasks of the Orthodox Church.

The liturgical Tradition of the Church enjoys unconditional authority. In their dogmatic impeccability, the liturgical texts of the Orthodox Church follow the Holy Scriptures and the creeds of the Councils. These texts are not just the creations of eminent theologians and poets, but part of the liturgical experience of many generations of Christians. The authority of liturgical texts in the Orthodox Church is based on the reception to which these texts were subjected for many centuries, when they were read and sung everywhere in Orthodox churches. Over these centuries, everything erroneous and alien that could have crept into them through misunderstanding or oversight was weeded out by Church Tradition itself; all that remained was pure and impeccable theology, clothed in the poetic forms of church hymns. That is why the Church recognized liturgical texts as the “rule of faith”, as an infallible doctrinal source.

The next most important place in the hierarchy of authorities is occupied by the works of the Church Fathers. Among the patristic heritage, the works of the Fathers of the Ancient Church, especially the Eastern Fathers, who had a decisive influence on the formation of Orthodox dogma, have priority importance for an Orthodox Christian. The opinions of the Western Fathers, consistent with the teachings of the Eastern Church, are organically woven into the Orthodox Tradition, which contains both Eastern and Western theological heritage. The same opinions of Western authors, which are in clear contradiction with the teachings of the Eastern Church, are not authoritative for an Orthodox Christian.

In the works of the Fathers of the Church, it is necessary to distinguish between the temporary and the eternal: on the one hand, that which retains value for centuries and has an immutable significance for the modern Christian, and on the other, that which is the property of history, that was born and died within the context in which This church author lived. For example, many natural scientific views contained in the “Conversations on the Six Days” of Basil the Great and in the “Accurate Exposition of the Orthodox Faith” by John of Damascus are outdated, while the theological understanding of the created cosmos by these authors retains its significance in our time. Another similar example is the anthropological views of the Byzantine Fathers, who believed, like everyone else in the Byzantine era, that the human body consists of four elements, that the soul is divided into three parts (reasonable, desirable and irritable). These views, borrowed from ancient anthropology, are now outdated, but much of what the mentioned Fathers said about man, about his soul and body, about passions, about the abilities of the mind and soul has not lost its meaning in our days.

In the patristic writings, in addition, it is necessary to distinguish what was said by their authors on behalf of the Church and what expresses the general Church teaching, from private theological opinions (theologumen). Private opinions should not be cut off to create some simplified “sum of theology”, to derive some “common denominator” of Orthodox dogmatic teaching. At the same time, a private opinion, even if its authority is based on the name of a person recognized by the Church as a Father and teacher, since it is not sanctified by the conciliar reception of church reason, cannot be placed on the same level with opinions that have passed such a reception. A private opinion, as long as it was expressed by the Father of the Church and was not condemned by the council, is within the boundaries of what is permissible and possible, but cannot be considered generally binding for Orthodox believers.

In the next place after the patristic writings are the works of the so-called teachers of the Church - theologians of antiquity who influenced the formation of church teaching, but for one reason or another were not elevated by the Church to the rank of Fathers (these include, for example, Clement of Alexandria and Tertullian). Their opinions are authoritative insofar as they are consistent with general Church teaching.

Of the apocryphal literature, only those monuments that are prescribed in worship or in hagiographic literature can be considered authoritative. The same apocrypha that were rejected by the church consciousness have no authority for the Orthodox believer.

Worthy of special mention are the works on dogmatic topics that appeared in the 16th-19th centuries and are sometimes called the “symbolic books” of the Orthodox Church, written either against Catholicism or against Protestantism. Such documents include, in particular: the responses of the Patriarch of Constantinople Jeremiah II to Lutheran theologians (1573-1581); Confession of Faith of Metropolitan Macarius Kritopoulos (1625); Orthodox Confession of Metropolitan Peter Mohyla (1642); Confession of Faith of the Patriarch of Jerusalem Dositheos (1672), known in Russia under the name “Epistle of the Eastern Patriarchs”; a number of anti-Catholic and anti-Protestant messages of the Eastern Patriarchs of the 18th - first half of the 19th centuries; Letter of the Eastern Patriarchs to Pope Pius IX (1848); Reply of the Synod of Constantinople to Pope Leo IX (1895). According to Archbishop Vasily (Krivoshein), these works, compiled during a period of strong heterodox influence on Orthodox theology, have secondary authority.

Finally, it is necessary to say about the authority of the works of modern Orthodox theologians on doctrinal issues. The same criterion can be applied to these works as to the writings of the ancient teachers of the Church: they are authoritative to the extent that they correspond to Church Tradition and reflect the patristic way of thinking. Orthodox authors of the 20th century made a significant contribution to the interpretation of various aspects of the Orthodox Tradition, the development of Orthodox theology and its liberation from alien influences, and the clarification of the foundations of the Orthodox faith in the face of non-Orthodox Christians. Many works of modern Orthodox theologians have become an integral part of the Orthodox Tradition, adding to the treasury into which, according to Irenaeus of Lyons, the apostles put “everything that relates to the truth,” and which over the centuries has been enriched with more and more new works on theological topics.

Thus, Orthodox Tradition is not limited to any one era, which remains in the past, but is directed forward to eternity and is open to any challenges of time. According to Archpriest Georgy Florovsky, “The Church now has no less authority than in past centuries, for the Holy Spirit lives it no less than in former times”; therefore, one cannot limit the “age of the Fathers” to any time in the past. And the famous modern theologian Bishop Kallistos (Ware) of Diokleia says: “An Orthodox Christian must not only know and quote the Fathers, but be deeply imbued with the patristic spirit and adopt the patristic “way of thinking”... To assert that there can be no more Holy Fathers is to assert that the Holy Spirit has left the Church."

So, the “golden age” begun by Christ, the apostles and the ancient Fathers will continue as long as the Church of Christ stands on earth and as long as the Holy Spirit operates in it.

DECR Communications Service/ Patriarchia.ru

All people around the world can read the Bible in whole or in part in their native language

— It would be interesting to know: what language did Jesus Christ speak?

— Many people believe that Christ used Aramaic. However, when talking about the original Gospel of Matthew, most biblical scholars point to Hebrew as the language of the Old Testament books. Disputes on this topic continue to this day.

—Can all peoples today read the Bible in their native language?

— According to Bible societies, back in 2008, the Bible was translated in whole or in part into 2,500 languages. Some scientists believe that there are 3 thousand languages in the world, others point to 6 thousand. It is very difficult to define the criterion: what is a language and what is a dialect. But we can say with absolute confidence: all people living in different parts of the globe can read the Bible in whole or in part in their native language.

The Koran is the holy book of Muslims

Just like the Bible, it contains revelations that were spoken by the Prophet Muhammad. The source that conveyed them into the mouth of the prophet is Allah himself. All revelations are organized into chapters - suras, which, in turn, are composed of verses - verses. The canonical version of the Koran contains 114 suras. Initially they had no names. Later, due to different forms of transmission of the text, the suras received names, some of them several at once.

The Koran is sacred to Muslims only if it is in Arabic. Translation is used for interpretation. Prayers and rituals are pronounced only in the original language.

Content-wise, the Quran tells stories about Arabia and the ancient world. Describes how the Last Judgment and posthumous retribution will take place. It also contains moral and legal standards. It should be noted that the Koran has legal force because it regulates certain branches of Muslim law.

The main criterion is that the Bible must be understandable.

— Which language is preferable for us: Russian, Ukrainian or Church Slavonic?

— The main criterion is that the Bible must be understandable. Traditionally, Church Slavonic is used during divine services in the Church. Unfortunately, it is not studied in secondary schools. Therefore, many biblical expressions require explanation. This, by the way, applies not only to our era. This problem also arose in the 19th century. At the same time, a translation of the Holy Scriptures into Russian appeared - the Synodal Translation of the Bible. It has stood the test of time and had a huge impact on the development of the Russian language in particular and Russian culture in general. Therefore, for Russian-speaking parishioners, I would recommend using it for home reading. As for Ukrainian-speaking parishioners, the situation here is a little more complicated. The fact is that the attempt at the first complete translation of the Bible into Ukrainian was undertaken by Panteleimon Kulish in the 60s of the 19th century. He was joined by Ivan Nechuy-Levitsky. The translation was completed by Ivan Pulyuy (after Kulish’s death). Their work was published in 1903 by the Bible Society. In the 20th century the most authoritative were the translations of Ivan Ogienko and Ivan Khomenko. Currently, many people are attempting to translate the entire Bible or parts of it. There are both positive experiences and difficult, controversial issues. So, it would probably be incorrect to recommend any specific text of the Ukrainian translation. Now the Ukrainian Orthodox Church is translating the Four Gospels. I hope that this will be a successful translation both for home reading and for liturgical services (in those parishes where Ukrainian is used).

7th century Four Evangelists. Gospel of Kells. Dublin, Trinity College

Spiritual food must be given to a person in a form in which it can bring spiritual benefit

— In some parishes, during the service, a biblical passage is read in their native language (after reading in Church Slavonic)…

— This tradition is typical not only for ours, but also for many foreign parishes, where there are believers from different countries. In such situations, liturgical passages from the Holy Scriptures are repeated in native languages. After all, spiritual food must be given to a person in a form in which it can bring spiritual benefit.

— From time to time, information appears in the media about some new biblical book that was allegedly previously lost or kept secret. It necessarily reveals some “sacred” moments that contradict Christianity. How to treat such sources?

— In the last two centuries, many ancient manuscripts have been discovered, which has made it possible to coordinate the view on the study of the biblical text. First of all, this concerns the Qumran manuscripts discovered in the Dead Sea area (in the Qumran caves). Many manuscripts were found there - both biblical and gnostic (that is, texts that distort Christian teaching). It is possible that many manuscripts of a Gnostic nature will be found in the future. It should be recalled that even during the 2nd and 3rd centuries. The Church fought against the heresy of Gnosticism. And in our time, when we are witnessing a craze for the occult, these texts appear under the guise of some kind of sensation.

Jewish Scripture

We should start with the scripture that is closest in content and origin to the Bible - the Jewish Tanakh. It is believed that the composition of the books here practically corresponds to the Old Testament. However, there is a slight difference in their location. According to the Jewish canon, the Tanakh consists of 24 books, which are divided into three groups. The criterion here is the genre of presentation and the period of writing.

The first is the Torah, or, as it is also called, the Pentateuch of Moses from the Old Testament.

The second is Neviim, translated as “prophets” and includes eight books covering the period from the arrival of the promised land to the Babylonian captivity of the so-called period of prophecy. There is also a certain gradation here. There are early and late prophets, the latter are divided into small and large.

The third is Ketuvim, literally translated as “records.” Here, in fact, the scriptures are contained, including eleven books.

We read the Word of God not to memorize, but to feel the breath of God Himself

— By what criteria can one determine a positive result from regular reading of the Holy Scriptures? By the number of memorized quotes?

— We read the Word of God not for memorization. Although there are situations, for example in seminaries, when exactly this task is set. Biblical texts are important for spiritual life in order to feel the breath of God Himself. In this way, we become familiar with the grace-filled gifts that exist in the Church, we learn about the commandments, thanks to which we become better, and draw closer to the Lord. Therefore, studying the Bible is the most important part of our spiritual ascent, spiritual life. With regular reading, many passages are gradually memorized without special memorization.