What is the Bible? History of creation, summary and interpretation of Holy Scripture

Books of Leviticus and Numbers

The third book of Moses was entitled in Old Testament times with the initial word Vayikra,

which means “and called,” i.e., God called Moses from the tabernacle to accept the Levitical laws.

The Greek name of this book is “The Book of Leviticus,” since it contains a set of laws about the service of the descendants of Levi (one of the sons of Jacob) in the Old Testament temple. The Book of Leviticus sets forth the order of Old Testament worship, which consisted of various sacrifices; the establishment of the priestly order itself is described through the initiation of Aaron and his sons; laws and rules for serving in the temple are given. The fourth book of Moses in Old Testament times was entitled with the initial word - Vayedabver

- “and said,” that is, the Lord spoke to Moses about the numbering of the people of Israel. The Greeks called this book the word “Numbers”, since it begins with the calculation of the Jewish people. In addition to the historical narrative about the wanderings of the Jews in the desert, the book of Numbers contains many laws - some new, some already known from

The books of Exodus and Leviticus, but repeated due to necessity. These laws and rituals lost their meaning in New Testament times. As the Apostle Paul explains in Hebrews, the Old Testament sacrifices were a type of the atoning sacrifice on Calvary of our Lord Jesus Christ. The prophet Isaiah also wrote about this (Isaiah 54).

The priestly vestments, altar, seven-branched candlestick and other accessories of the Old Testament temple, made by revelation to Moses on Mount Sinai and in accordance with heavenly worship, are used in a slightly modified form in our services.

Deuteronomy

The fifth book of Moses was entitled in the Old Testament with the initial words Elle-gaddebarim

- “these are the words”;

in the Greek Bible it is called “Deuteronomy” in its content, since it briefly repeats the set of Old Testament laws. In addition, this book adds new details to the events described in previous books. The first chapter of Deuteronomy tells how Moses began to explain the Law of God in the land of Moab, on the other side of the Jordan, on the plain opposite Suph, at a distance of eleven days' journey from Horeb, on the first day of the eleventh month in the fortieth year after the exodus of the Jews from Egypt. Since by the end of Moses’ life almost no one remained alive from the people who heard the Law of God on Sinai, and a new generation born in the desert was about to enter the Promised Land, Moses, caring about preserving true worship of God in the Israeli people, before his death decided to collect the Law of God in a separate book. In this book, Moses, with promises of benefits and threats of punishment, wanted to imprint as deeply as possible in the hearts of the new Israeli generation the determination to follow the path of serving God. The book of Deuteronomy contains a brief repetition of the history of the wanderings of the Jews from Mount Sinai to the Jordan River (Deut. 1–3 chapters).

Next it contains a call to observe the Law of God, reinforced by reminders of the punishment of apostates

(Deut. 4-11 ch.).

Then there are more detailed repetitions of those laws of Jehovah, to which Moses called the people of Israel to observe

(Deut. 12-26 ch.).

At the end, the last orders of Moses for the establishment of the Law of God in the people of Israel are described

(Deut. 27–30 chapters),

Moses’ testament is given and his death is described

(Deut. 31–34 chapters).

Prophecies about the Messiah in the books of Moses

In the books of Moses there are the following important prophecies about the Messiah (Christ): about the “Seed of the Woman”, which will crush the head of the serpent-devil (Gen.

3,

15);

that in the Descendant of Abraham all nations will be blessed

(Gen.

22:

16–18);

that the Messiah will come at a time when the tribe of Judah will lose its civil power

(Gen.

49:10);

about the Messiah in the form of a rising star (Num.

24:17

).

And finally, about the Messiah as the greatest Prophet

(Deut. 18, 15–19).

The biblical account of the origin of the world and man

“I believe in one God, the Father, Almighty, Creator of heaven and earth, of all things visible and invisible,” we confess in the Creed. Thus, for us the world is not only an object of scientific knowledge, but also an object of faith. No matter how many secrets science reveals in the field of physics, chemistry, geology, cosmology, and so on, fundamental questions will still remain unresolved for humans: where did the very laws of nature and the particles from which the world was formed come from, what is the purpose in all that we surrounds, and what is the purpose in human life? Science is not only powerless to answer these questions that concern us, but, in fact, they go beyond the scope of the subject of science. The revealed Bible answers these questions. The God-seer Prophet Moses in the first chapters of the Book of Genesis placed a narrative about God’s creation of the world and man. Until very recently, science could not say anything convincing about the origin of the world. Only in the 20th century, thanks to major advances in the fields of astronomy, geology and paleontology, the history of the origin of the world began to lend itself to scientific research. And what? It turns out that the world arose in the same sequence as described by the prophet Moses. Although the prophet Moses did not set out to give a scientific account of the origin of the world, his narrative was still many millennia ahead of modern scientific discoveries. His description for the first time testified that the world is not eternal, but arose in time and in a gradual (evolutionary) order. Modern astronomers also came to the conclusion that the universe did not always exist when they established that the universe is continuously expanding, like an inflating balloon. 15–20 billion years ago the entire universe was condensed into a microscopic point, which, as if exploding, began to expand in all directions, gradually forming our visible world. Moses divided God's creation of the world into seven periods, which he symbolically designated “days.” During six “days” God formed the world, and on the seventh He rested... from His works

(Genesis 2:2).

How long these days lasted, Moses does not determine. The seventh day, during which the history of mankind unfolds, has been going on for many millennia. The number 7 itself in Holy Scripture is often used in a symbolic rather than quantitative sense. It denotes completeness, completeness. In the beginning God created heaven and earth (Gen. 1:1)

- with these words the Bible covers everything that God created: our visible material world and that spiritual angelic world that is beyond our physical observation.

The word created

says that the world was created by God “out of nothing.”

Many modern scientists come to the same conclusion: the deeper nuclear physics penetrates into the foundations of matter, the more its emptiness and immateriality are revealed. Apparently, even the quarks that make up protons are not elementary and solid particles. It turns out that matter is an inexplicable state of energy. Reading further the biblical description of the origin of the world, we see that it essentially and in general terms coincides with what modern science says about this. Leaving aside the details of the origin of the galaxies after this “in the beginning,” Moses’ narrative focuses on the formation of our earth and the things that fill it. So, on the first “day”: And God said: let there be light (Gen. 1, 3).

These words probably indicate the moment when the interstellar gases and dust from which the solar system was formed became so condensed under the influence of the gravitational field that a thermonuclear reaction (conversion of hydrogen into helium) began in the center of the gas ball with abundant emission of light.

This is how the Sun came into being. Light is the factor that later made possible the emergence of life on Earth. From the same gases and dust from which the Sun was formed, comets, meteorites, asteroids, protoplanets, etc. were also formed. This entire mass of gases, dust and solid bodies spinning and rushing through space was called “water” by Moses. Under the influence of mutual attraction, it eventually formed into planets. This is the “separation of the water (Gen. 1:7),

which is under the firmament, from the water, which is above the firmament” of the second “day” of creation.

This is how the solar system, or, according to the Bible, “the sky,” took on its complete form. At first, the Earth, like other planets, was hot. Water evaporating from the depths of the earth enveloped the Earth in a thick, dense atmosphere. When the Earth's surface cooled enough, water began to fall as rain and oceans and continents were formed. Then, thanks to water and sunlight, plants began to appear on Earth. This is the third “day” of Creation. The first green plants, aquatic microorganisms, and then giant land plants began to cleanse the earth's atmosphere of carbon dioxide and release oxygen. Before this time, if anyone from the surface of the Earth looked at the sky, he would not be able to see the outlines of the Sun, Moon or stars, because the Earth was shrouded in a dense and opaque atmosphere. An example of such an opaque atmosphere is given to us by our neighboring planet Venus. That is why the appearance of the sun, moon and stars was timed by Moses to coincide with the “day” after the appearance of plants, that is, the fourth. Not knowing this fact, atheist materialists at the beginning of the 20th century ridiculed the Bible's account of the creation of the sun after the appearance of plants. According to the Bible, scattered sunlight reached the surface of the Earth from the first “day” of creation, although the outline of the Sun was not visible. The appearance of oxygen in the atmosphere in sufficient quantities made it possible for the emergence of more complex life forms - fish and birds (on the fifth “day”), then animals and, finally, man himself (on the sixth “day”). Modern science also agrees with this sequence of appearance of living beings. In the biblical narrative, many scientifically interesting details about the appearance of living beings are not given by Moses. But it must be recalled that the purpose of his narration is not a list of details, but to show the First Cause of the world and the wisdom of the Creator. Moses concludes his account of the creation of the world with the following words: and God saw everything that He had created, and behold, it was very good.

In other words, the Creator had a specific goal when creating the world: so that everything would serve good and lead to good. Nature has still retained the stamp of goodness and testifies not only to the wisdom, but also to the goodness of the Creator. According to the Book of Genesis, man was the last to be created. Modern science also believes that man appeared relatively recently, after the emergence of other groups of living organisms. In the matter of the origin of man, the difference between science and the Bible lies in the method and in the goal. Science is trying to establish the details of the origin of the physical side of man - his body, and the Bible speaks of man in his complete form, having, in addition to the body, a rational, god-like soul. However, the Bible also states that the human body is created from “earth,” that is, from elements, like the bodies of other animals. This fact is important because the Bible confirms the fact of physical intimacy between the animal kingdom and man. But at the same time, the Bible emphasizes the exclusive position of man in the animal world, as the bearer of the “breath of God” - the immortal soul. This godlikeness attracts a person to communicate with God and with the spiritual world, to moral improvement. Ultimately, earthly pleasures alone cannot satisfy a person’s spiritual thirst. These facts confirm the testimony of the Bible that man is not simply the highest level of evolution of the animal world, but is a representative of two worlds simultaneously: the physical and the spiritual. Revealing this secret helps a person find his place in the world, see his calling to do good and strive for God.

In conclusion of our brief review of the biblical narrative about God’s creation of the world, it should be said that in this narrative, as in the subsequent story about the life in paradise of our first parents and their fall, in addition to events that are understandable, there are symbols and allegories, the meaning of which is not fully given to us understand. The meaning of symbols lies in the fact that they give a person the opportunity, bypassing details that are difficult to understand, to assimilate the main thing that God reveals to man: in this case, the cause of evil in the world, disease, death, etc. Science continues to intensively study the world. It reveals many new and interesting things that help a person understand the Bible more fully and deeply. But often, as the saying goes, it turns out that scientists “can’t see the forest for the pines.” Therefore, for a person, understanding the principles should be more important than knowing the details. The significance of the Bible is that it reveals to us the principles of existence. Therefore, it has an enduring, eternal meaning.

LiveInternetLiveInternet

Alexander Zorich

The Quedlinburg Itala, a luxuriously illustrated manuscript of the Old Testament in Latin, is close in style to the Vatican Virgil.

Quedlinburg Itala was created in the beginning. V century, presumably in Rome. Then it came to Germany and was donated to the Quedlinburg monastery in the 10th century. Emperor Otto I (whose daughter, Matilda, was the abbess of the said monastery).

This codex is the first known Latin illustrated Old Testament. Unfortunately, very little of the book has survived: six sheets, the state of which leaves much to be desired (ill. 8, ill. 9).

Ill.8. First Book of Samuel. Quedlinburg Italia. OK. 425. Berlin, State Library.

Ill.9. First Book of Samuel. Quedlinburg Italia. OK. 425. Berlin, State Library.

A representative source of early Christian artistic motifs in book miniatures is the so-called Viennese Book of Genesis, dating back to the 6th century. This codex, executed with outstanding skill on purple-dyed parchment, is rightfully considered one of the masterpieces of world art. Created in one of the largest Greek-speaking centers of Christian culture (either in Antioch or Jerusalem), this manuscript had a significant influence on subsequent plot, composition and color schemes of book illustration not only in the east, in Byzantium, but also in the west - in Italy.

In the Vienna Book of Genesis we encounter such scenes as the Flood (Ill. 12), the Blessing of Ephraim and Manasseh, Eliezer and Rebekah at the well (Ill. 10), the Temptation of Joseph, Joseph in prison, the Flight of Joseph, etc. Moreover, if in the Vatican and the Roman Virgil and the Quedlinburg Itale, the accompanying illustrations are either placed on separate pages, or at least separated from the text by massive red borders, then in the Vienna Book of Genesis for the first time there is a free combination of text and miniature on one page, serving as a graphic commentary on the corresponding fragment of scripture. Thus, the image and the sacred text penetrate each other, forming the integrity of a new order.

Ill. 10. Eliezer meets Rebekah at the well. Vienna Book of Genesis. ser. VI. Vienna, National Library.

Ill. 11. Eliezer, Rebekah and Isaac. Ashburnham Pentateuch. VII century Paris, National Library. A century later, in the Spanish manuscript of the Mosaic Pentateuch, the same plot - Rebecca and Eliezer - is realized much more fully than in the Vienna Book of Genesis. However, the charm that the Greek masters were able to impart to this plot will be irretrievably lost.

In Fig. 10 we see an episode from the 24th chapter of the Book of Genesis. Rebekah, daughter of Bethuel, comes from the city of Nahor to a spring for water. Abraham's servant, Eliezer, is looking for a girl who would make a worthy marriage match for his master's son. He finds Rebekah’s candidacy quite worthy, for “The maiden was beautiful in appearance, a maiden whom her husband had not known.” (Genesis 24:16). Then Eliezer asks Rebekah for a drink. Rebekah not only gives Eliezer a pitcher of water, but also gives his camels water.

Nahor is depicted as a walled city of typical late Roman architecture, viewed from above and from the side. The half-naked woman personifies either spring or the nymph of the spring. It is curious that we simultaneously see two Rebekahs in the illustration. Rebekah-1 is just walking to the source with a jug on her shoulder, while Rebekah-2 is already giving Eliezer water.

The action is presented with all the simplicity and expression inherent in pantomime: Rebekah hugs the jug with one hand, puts her left foot on the edge of the camel water and lets Eliezer drink, touching it with her fingertips in a friendly manner. The figures are silhouetted against a landscape that is almost pure: only a miniature city and the road to the well are depicted. The illustration contains only what is necessary for the plot - and nothing more.

Ill. 12. Flood. Vienna Book of Genesis. Ser. VI century Vienna, National Library. “And all flesh that moved on the earth lost life, and birds, and cattle, and wild beasts, and every creeping thing that creepeth on the earth, and all people.” (Genesis 7:21)

Ill. 13. Flood. Ashburnham Pentateuch. VII century Paris, National Library. In comparison with a similar plot from the Vienna Book of Genesis, we find here a significantly simplified composition and a lack of genuine dynamics. In the background is Noah's Ark.

The miniature illustrating the great flood was made with particular expression and dynamism (ill. 12). The center of the composition is occupied either by the top of a mountain, or by some kind of stepped structure like a Babylonian ziggurat, which is about to disappear under the boiling breakers of water. Around her, animals and people are circling in search of salvation: men, women, a baby. In several wavy lines in the lower right part of the miniature, you can guess snakes - “reptiles crawling on the ground.” Visually, the horizon is very close: the figures “in the distance”, depicted against the black-blue-blue background of the jets of a fifteen-day downpour, have the same dimensions as in the foreground. The artist seemed to descend almost to the level of the water - of course, taking the viewer with him. This feeling is enhanced by the fact that we are also shown parts of human bodies that are under water - something that in real life we would only be able to see if we were in close proximity to drowning people. Let us pay attention to how responsibly the miniaturist approaches the verisimilitude of the image, weakening the color saturation and blurring the contours of the underwater details of his story about the death of the human race.

Speaking of early Christian manuscripts, one cannot ignore one significant codex with an unfortunate fate, known as the Book of Genesis Coton.

Ill. 14. On the left are Abraham and the angels, on the right is Lot’s house. Fragments of miniatures from the Book of Genesis of Koton. VI century London, British Library.

This book, written in Greek (most likely in Alexandria) and richly illustrated with 250 miniatures, is usually dated to the first half of the 6th century. It was presented by two Greek clergy to the English king Henry VIII (1491-1555, king of England from 1509). Queen Elizabeth passed on the precious codex to her mentor, Sir John Fortescue, and the latter in turn to Sir Robert Coton (1571-1631), an avid collector of ancient manuscripts. Alas, on October 23, 1731, a fire broke out in Westminster Abbey, in the so-called Ashburnham House, where both the Coton collection and the Royal Library were kept at that time. Many valuable books were lost. In particular, the Book of Genesis of Coton was very badly burned; only 150 fragments, charred at the edges, survived from it (ill. 14).

But even the little that has survived is enough to judge the very high artistic level of the illustrations. The composition and technical execution of the miniatures were so perfect that, as shown at the beginning of the 20th century. Finnish scientist Tikkanen, they served as sketches for mosaics with scenes from the Book of Genesis in the Venetian Cathedral of St. Mark. (Of course, it cannot be said that the Italian masters used exactly the Coton copy of the manuscript; perhaps they were inspired by some other copy - but this particular book.)

Note that up to this point we have talked only about the illustrated texts of the Old Testament. Now in our narrative we must meet for the first time the illuminated manuscripts of the New Testament, that is, the gospels.

It can be considered generally accepted that the four canonical gospels were written down between 60 and 100 AD. Around 200, these texts were selected from a wide range of Christian writings and received canonical recognition. For the church hierarchs of that time, the main criterion in making this difficult choice was, on the one hand, the direct connection of the gospels of Matthew, Mark, Luke and John with apostolic times and, on the other hand, the most orthodox presentation of the teachings of Jesus Christ and the essence of theophany.

The earliest surviving manuscripts containing fragments of the gospels and works of the early Church Fathers date back to the 2nd century; but the earliest copies of illustrated New Testament codices that we have date back to the 6th century. These illuminated manuscripts, regardless of their origin - Western or Eastern - were intended for liturgy and were originally created as important church shrines. The luxuriously illustrated gospel is endowed with sacred power, becomes an object of worship and remains so throughout the Middle Ages.

The most notable books of the sixth century are: the Gospel of Rossano (in Greek), the Syriac Gospel of Rabula (in Aramaic), and the Gospel of St. Augustine of Canterbury (in Latin), which is also often called the Cambridge Gospel due to its location. All three manuscripts have come down to us in fragments. Only the Aramaic Gospel has a precise date, 586, added to the text by the scribe Rabula, a monk from the monastery of St. John in Zagba (Mesopotamia). Based on the stylistic features of design and font, the Rossan Codex dates back to the middle, and the Cambridge Codex - to the end of the 6th century.

These codes present us with an already formed canon of gospel illustrations, which will, with minor changes, be shared by both Western and Eastern Christianity over the next six centuries. The most stable element of this canon is the portrait of the evangelist (as a rule, accompanied by a corresponding symbol).

Thus, in the codices from Rossano and Cambridge, each gospel was preceded by a portrait of its author, which occupied a separate page. St. has been preserved to this day in the Rossan Codex. Mark (ill. 15), in Cambridge - St. Luke (ill. 16). In the Rossano Gospel there is also a frontispiece with busts of all four evangelists, and in the Rabula Gospel portraits of Mark, Luke, John and Matthew appear in connection with the table of canons.

Ill. 15. St. Mark. Gospel from Rossano. Ser. VI century Rossano, Museum of the Episcopal Palace. Female figure dictating St. Mark, in all likelihood, is St. Sophia, personification of Divine Wisdom.

Ill. 16. St. Luke. Gospel of St. Augustine of Canterbury. Con. VI century Cambridge, Corpus Christi College Library.

Ill. 17. Table of canons. St. John (left) and St. Matthew (right). Gospel of Rabula. 586 Florence, Laurentian Library. In the book that lies on the lap of St. Matthew, with high magnification you can read in Aramaic: “The birth of Jesus Christ was like this...” (Matthew 1:18). In the scroll of St. John: “In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God...” (John 1:1).

On the pediment of the arch framing the portrait of Luke from the Cambridge Gospel, we see a winged calf - one of the four canonical symbols of the evangelists, called tetramorphs in accordance with Greek tradition. Tetramorph, “four beasts,” appears in the visions of the Old Testament prophets Ezekiel (Ezekiel 1:1-14, 10:1-22), and in a slightly different form in Daniel (Dan 7:1-18) and in the Revelation of John the Evangelist, then there is the Apocalypse (Rev 4:7-8). When early Christian writers reflected on the Old Testament heritage, they identified the beasts in the visions with the four evangelists. Four different systems of identifications are known, belonging, respectively, to Irenaeus of Lyons, Augustine the Blessed, Pseudo-Athanasius and Jerome. But since of the named theologians it was Jerome who was the author of the generally accepted translation of the Bible into Latin in the Middle Ages (the Vulgate), it was his interpretation, set out in the preface to the Gospel of Matthew, that became the most widespread in the pictorial canon. According to Jerome, the tetramorph is defined as follows: St. Matthew – imago hominis, winged man (sometimes taken as an angel), St. Mark – imago leonis, lion; St. Luke – imago vitulis, Taurus; St. John – imago aquilae, eagle.

Why exactly this way and not otherwise? In his preface to his commentary on the Gospel of St. Matthew Jerome explains that St. Matthew was the very first evangelist, followed by St. Mark, first bishop of Alexandria, St. Luke was the third and finally St. John is the fourth. This sequence - Matthew, Mark, Luke, John - is compared by Jerome to the order of appearance of the “faces” of the four beasts from the vision of the prophet Ezekiel (Ezekiel 1:10): man, lion, calf, eagle.

Ill. 18. Ascension. Gospel of Rabula. 586 Florence, Laurentian Library. In the center, under the feet of Jesus Christ, there is a tetramorph.

The wings are “full of eyes” in accordance with the literal reading of the Revelation of John the Theologian.

All animals, in accordance with the visions of Ezekiel and John the Theologian, are usually depicted as winged, although there are manuscripts where there is a departure from this canon. Also, some artists, starting from John the Theologian, who reports “And each of the four living creatures had six wings around, and within they were full of eyes” (Rev 4:8), covered the wings with eyes (ill. 18).

Another important element in the design of the Gospel texts are the tables of the canons. Around 250, the Alexandrian Greek Ammonius made the first attempt to compile a compilation of correspondences between parallel episodes from the four canonical gospels. Taking as a starting point the gospel of St. Matthew, he disassembled it into separate episodes (355 in total), renumbered them and placed the numbers in a column one below the other. Then in three adjacent columns he placed the numbers of the corresponding episodes (if any) from the three other gospels. Of course, the full table of correspondences turned out to be very large and did not fit on one page. In addition, not every episode from the Gospel of St. Matthew can be found in all three (and sometimes at least two) gospels. On the other hand, Matthew lacks a number of information given by Mark, Luke or John. Because of this, the table of canons compiled by Ammonius was not yet an exhaustive reference apparatus.

Ammonius' system was revised in the 4th century. Eusebius of Caesarea, famous Church historian. He, firstly, made changes to the primary division of the Gospel of St. Matthew for individual episodes. And, secondly, he compiled tables that took into account all possible pairwise parallels between the gospels. There were ten tables in total, and prefixes were added to the ammonium episode numbers in the form of a table number, where additional cross-references should be looked for. However, only the first table included four columns. There are three of them in tables II-IV, and two in V-IX (for example, in Fig. 17 we see part of table VII, indicating the correspondence between the gospels of Matthew and John). Table X contains unique episodes for which there are no matches.

This unique “hypertext” system was called the Eusebian Canon and was used throughout the Middle Ages. The very principle of several parallel columns of links suggests to the designer a suitable graphic solution: columns of numbers visually remind us of pillars, columns - therefore, they should be placed between these architectural elements. In turn, above the columns with classical, usually Corinthian capitals, an arch or an entire arcade suggests itself. It is precisely this architectural style that we find in the design of tables from the Gospel of Rabula (ill. 19) and most other manuscripts.

Ill. 19. Table of canons. Along the edges are scenes from the Old Testament. Gospel of Rabula. 586 Florence, Laurentian Library.

Finally, the third fairly common element in the design of the New Testament are scenes from the history of the earthly incarnation of Jesus Christ, that is, actual plot illustrations in the modern sense of the word. At the same time, miniature illustrations could be collected in blocks on one page (ill. 20) in front of the text, frame portraits of the evangelists - for example, as “frescoes” on architectural design details (ill. 16), - combined with the text (ill. 21) or appear in the most familiar form for us as independent paintings on separate pages (ill. 18).

Ill. 20. Twelve scenes from the New Testament. Gospel of St. Augustine of Canterbury. Con. VI century Cambridge, Corpus Christi College Library.

Ill. 21. Christ and Pilate. Gospel from Rossano. Ser. VI century Rossano, Museum of the Episcopal Palace.

Ill. 22. Christ and Barabbas. Gospel from Rossano. Ser. VI century Rossano, Museum of the Episcopal Palace.

The Rossan Gospel gives a good idea of early New Testament illustration. Like the Viennese Book of Genesis, the Rossano Gospel is written in silver on purple-dyed parchment. The illuminators of this codex were able to select successful combinations of the colors used in the illustrations with the purple of the pages.

By the will of the illuminator, the heroes of the gospel stories are fluent in the language of theatrical pantomime, thanks to which it was possible to create expressive, eloquent scenes. Such, for example, are two illustrations with Pilate, who demands the people of Israel to choose between Jesus and the robber Barabbas (ill. 21 and ill. 22).

Individual episodes of history are combined in the same picture. The figures are organized in a two-level composition, with the levels being schematically separated by a line. At the top level of Fig. 21, Pilate presides over the tribunal, Christ stands before him. At the lower level, Judas returns the ill-fated thirty pieces of silver - a strange (and certainly erroneous from the point of view of the gospel truth) decision of the artist, considering that in the text this episode is located in a different place. There, in the lower right corner, you can see Judas hanging himself.

In Figure 22, the people demand death for Jesus. On the lower level are Jesus and the chained Barabbas (right). On both sheets, Christ is highlighted with a halo with a cross inscribed in it, symbolizing his divine origin. One can feel throughout the illuminator’s desire to make the composition as rich and eloquent as the text of the Gospel itself. For example, next to Barabbas the artist placed the inscription Βαραβιας - to eliminate the very possibility of spectator error. And so that there is no double reading in the viewer’s identification of Pilate, imaginifera are painted behind his back - standard bearers with special standards containing wooden images (imago) of the Roman emperor.

We have briefly examined the main features inherent in the precious illustrated manuscripts of the New Testament of the 6th century. using the example of the Rossan Codex, as well as the Gospels of Rabula and St. Augustine of Canterbury.

It is curious that these codes can symbolize the three main directions of the spread of Christianity at that time - and, accordingly, the three trends in Christian art of the 6th century. The Latin Gospel of St. Augustine was created in Rome and thus stands closest to Western European Christian art proper. Written either in Antioch or in Jerusalem in Greek, the Rossan Gospel correlates with the art of the Eastern Church - but not the whole, but precisely that most orthodox part of it, which was politically controlled by the Byzantine state.

But the Aramaic Gospel of Rabula anticipates that exotic branch of Christian civilization, which, unlike the two previously mentioned, was destined for a relatively short-lived popularity among Asian pagans and gentiles in subsequent centuries - in Iraq, Iran and further east to Mongolia - then marginalized under the pressure of Islam, Buddhism and ethnic cults of Inner Asia and almost complete oblivion after the 13th century. We are, of course, talking about the Nestorian branch of Christianity, which was classified as heretical by the orthodox supporters of the Nicene Confession of Faith. However, the Gospel of Rabula precisely symbolizes this marginal heretical branch of Christianity, because in itself it does not contain anything Nestorian: it is the usual canonical quadruple gospel, which in the Syro-Mesopotamian tradition is usually called Peshitta (i.e. “Simple [edition]”) .

The scribe Rabula left a fairly detailed commentary on the manuscript, located at the end of the book: in particular, it contains a list of names of the monks who took part in the creation of the codex. At the end of his afterword, Rabula placed a special spell designed to protect the book from the attacks of unscrupulous readers:

“This book is the property of the holy community of St. John in Zagba. If someone takes it somewhere in order to read it, or rewrite it, or re-bind it, or hide it, or cut out a sheet from it, whether covered with writing or not, even if he performs these actions without causing damage to the book, and thus more with causing damage, may he be equated with a destroyer of cemeteries. With prayer to all saints. Forever, amen."

Both the Gospel of Rabula, and the Rossan Gospel, and the Vienna Book of Genesis, which we examined earlier, reflect the results of a general Christian, then still non-confessional, creative search aimed at developing an aesthetic canon and the visual technique of book miniatures. While not the subject of Western European art proper, they - either directly or through lesser-known manuscripts created under their spell - shaped the tastes of the then few artists in Italy and, possibly, Visigothic Spain. Alas, the coming era, which became the “Dark Ages” for Western Europe, left behind only a few illuminated manuscripts. And yet, we can safely say that the early Christian, pan-Christian artistic heritage played a decisive role in the preservation of Western European book culture and laid the foundations for the rapid development of miniature painting, which began in Ireland from the end of the seventh century, and on the continent - from the second half of the eighth century.

(c) Alexander Zorich, 2003, 2012

The history of the Bible.

In those days, it was already customary to draw up contracts and messages in writing, as well as write down the names of prominent people (judges, high-ranking city officials, etc.), draw up genealogies, and record the offerings and loot made. In this way, archives were created that served as sources of documents, the most important of which were later edited and received the form of the Scriptures that have survived to this day. Thus, each part of the Old Testament is a mixture of different literary genres. Finding out the reasons why the documents and, consequently, the information contained in them are collected in such an incredibly strange mixture is one of those tasks that specialists will have to solve.

The Old Testament is a contradictory, diverse whole, originally based on oral tradition. Therefore, it is interesting to compare its formation with a similar process that could well have occurred in another time and place, when primitive literary creativity was also emerging there.

Take, for example, the birth of French literature during the period of the Kingdom of the Franks. The main way to preserve information about significant deeds here was also oral tradition. And such information included wars, often fought in defense of Christianity, and other high-profile events that gave birth to their heroes. All of them - sometimes even centuries later - inspired poets, chroniclers and writers to compose various kinds of “cycles”. In this way, starting from the eleventh century AD, these narratives began to appear in verse, where legends and legends were mixed, which became the first monuments of the new epic. The most famous of them is “The Song of Roland” - a romantic song glorifying the military feat of the knight Roland, who commanded the rearguard of Emperor Charlemagne on his way home from a military campaign in Spain. Roland's self-sacrifice is not just an episode invented to complete the story. It actually happened on August 15, 778 after an attack on the rearguard of the warlike Basques living in the mountains. As we see, this literary work is not just a legend. It has a historical basis, but no historian would take the entirety of The Song of Roland literally.

This parallel between the birth of the Bible and secular literature seems to accurately reflect the real state of affairs. However, it is in no way intended to reduce the text of the Bible as it has come down to us to just a kind of “archive” where collections of myths and traditions are stored. Many of those who systematically deny the very idea of God try to present it in this light. For a believer, there are absolutely no barriers to faith in the holy realities of the Universe, in the fact of God’s transmission of the Ten Commandments to Moses, in the participation of God in human affairs, as, for example, in the time of Solomon. At the same time, this does not prevent us from believing that the texts that have reached us only indicate that specific events actually occurred, but the details describing them should be subjected to strict critical analysis. And the reason for this criticism is the influence of human factors in the process of translating the original oral tradition into the language of the Scriptures. Moreover, it must be admitted that this influence is very great.

Old Testament Scriptures

The Old Testament is a collection of literary works that vary significantly in size and style. They were written in different languages. The period of their writing covers more than nine centuries, and they are based on oral traditions. Many of these works were subject to revisions and additions in response to events or to meet specific requirements. Often this was done in very different and even very distant eras from each other.

Such mass literary production probably reached its peak during the earliest period of the Kingdom of Israel, around the eleventh century BC. It was during this period that at the royal court, among the members of the royal family, a kind of “guild” of scribes arose - copyists of such literature. These were educated and intelligent people, whose role was not limited to copying texts. It is to this period that the first incomplete Scriptures mentioned in the previous chapter most likely date back. There was a special reason for recording these works. In those days, a whole series of songs had already been composed, there were the prophecies of Jacob and Moses, the Ten Commandments, as well as more general information - the foundations of legislation that laid down the religious traditions, on the basis of which the law was subsequently formulated. All of these texts are separate fragments found in different places in different versions of the Old Testament.

And only later, perhaps in the tenth century BC, was the text of the Pentateuch called the Yahwist[12] written. This text formed the backbone of the first five Books attributed to Moses. Even later, the Elohist[13] and the so-called Sacerdotal[14] version were added to this text. The original Yahwist text covers the period from the Creation of the world until the death of Jacob. Its homeland of origin is the Southern Kingdom, Judea.

The periods corresponding to the end of the ninth and mid-eighth centuries BC are marked by the prophecies of Elijah and Elisha. At this time, their mission was clearly defined and their influence spread. Their Scriptures have reached us. This was also the time of the appearance of the Elohist text of the Pentateuch, covering a much shorter period than the Yahvist, since it is limited only to information relating to Abraham, Jacob and Joseph. The Scriptures of Joshua and the Book of Judges also date from this time.

Eighth century BC witnessed the appearance of writing prophets - Amos and Hosea in Israel, as well as Isaiah and Micah in Judea.

The fall of Samaria in 721 brought an end to the Kingdom of Israel. His entire religious heritage passed to the Kingdom of Judah.

The collection of Proverbs dates from this time. Deuteronomy was also written at the same time. This period, among other things, is also significant in that both texts, the Yahwist and the Elohist, were combined into a single Scripture - the Pentateuch. This is how the Torah came into being.

The reign of Josiah in the second half of the seventh century BC. coincided with the appearance of the Prophet Jeremiah, but his work took on distinct forms only a century later.

Before the first exile of the people of Israel to Babylon in 598 BC. saw the light of the Book of Zephaniah, Nahum and Habakkuk. And during the first exile, Ezekiel had already prophesied. After the fall of Jerusalem in 587, the second exile began, lasting until 538 BC.

The book of Ezekiel, the last great Prophet, the Prophet in exile, was brought into the form in which it came to us only after his death. This was done by the scribes who became his spiritual heirs. These same scribes again turned to the Book of Genesis in the third, so-called Sacerdotal version and added to it a section telling about the period from the Creation of the world to the death of Jacob. Thus, the third version of the text was inserted into the internal structure of the Yahwist and Elohist texts of the Torah. We will see this when we turn to Books written approximately two to four centuries earlier. It should be said that around the same time as the third text, another Book of the Old Testament was created - “Lamentations of Jeremiah”.

By order of Cyrus in 538 BC. The Babylonian exile was put to an end. The Jews returned to Palestine, the Jerusalem Temple was rebuilt. Prophetic activity resumed and resulted in the Books of Haggai, Zechariah, the third Book of Isaiah, the Books of Malachi, Daniel and Baruch (the latter written in Greek).

The time after the exile is also the period of the appearance of the Books of Wisdom. By 480 BC. The Book of Proverbs of Solomon was finally written, and in the middle of the fifth century BC. - Book of Job. In the third century BC. The Books of Ecclesiastes, or Preacher, the Song of Solomon, I and II Chronicles, the Books of Ezra and Nehemiah appeared. The Book of Wisdom of Jesus, son of Sirach, appeared in the second century BC. One century before the birth of Christ, the Book of the Wisdom of Solomon, I and II Books of Maccabees were written.

The time of writing of the Books of Ruth, Esther, Job, as well as the Books of Tobit and Judith, is difficult to accurately determine.

All periods of writing of the Books are indicated taking into account the fact that later corrections and additions could be made to them, since the Scriptures of the Old Testament were finally formed into a single whole only approximately one century before the birth of Christ, and for many they became final only a century after Christ.

Thus, the Old Testament appears before us as a literary monument of the Jewish people, illuminating its history - from the emergence to the advent of Christianity. The parts that make up the Old Testament were written, expanded, and revised between the tenth and first centuries BC.

This is in no way the author's personal point of view. The most important historical information used in this review was gleaned from the article “The Bible”, written for the Encyclopedia Universalis[15], authored by theology professor J.P. Sandros. To understand what the Old Testament is, it is very important to have information that in our time has been established and substantiated by highly qualified specialists.

All these Scriptures contain Revelation, but everything that we have now is, first of all, the result of human labors, the purpose of which was to cleanse the Scriptures of everything that seemed superfluous and unnecessary to these people. They handled the texts arbitrarily, either to satisfy their own vanity, or to obey someone else's demands or circumstances.

Comparing these objective data with the interpretations of various prefaces to modern mass editions of the Bible, you understand that their authors also treat the facts very arbitrarily. They are silent about fundamental information about the writing of individual Books, they are full of ambiguities that mislead the reader. Many prefaces or introductions given in such comments do not adequately reflect the real state of affairs. The amount of factual material presented in them is reduced to a minimum, and instead of it, readers are instilled with ideas that do not correspond to reality. For example, with regard to the Scriptures that have undergone modifications and additions several times (such as the Pentateuch), it only mentions that subsequently they could presumably be supplemented with certain points. Thus, in numerous prefaces, there is a detailed discussion of far from the most important passages of Scripture, and decisive facts that require detailed explanations are simply suppressed. Therefore, it is sad to see how erroneous information about the Bible continues to be published in mass quantities.

Torah, or Pentateuch

The name "Torah" is of Semitic origin. The Greek title, "Pentateuchos", translated into Russian as "Pentateuch", indicates that this Scripture consists of five parts-books: Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers and Deuteronomy. They form the five main elements of the canonical text of the Old Testament, which includes thirty-nine sections.

These five parts tell the story of the origin of the world and subsequent events up to the entry of the Jewish people into Canaan, the land promised to them upon their return from Egypt, or more precisely, until the death of Moses. The narration of all these events, however, only frames a whole series of provisions designed to regulate the religious and social life of the Jewish people. Hence the name - Law or Torah.

In both Judaism and Christianity, for many centuries Moses was considered the author of the Pentateuch. This point of view was probably based on what God Himself said to Moses: “And the Lord said to Moses: Write this for a memorial in a book, and teach Jesus that I will completely blot out the memory of the Amalekites from under heaven” (Exodus 17:14). And further, where we talk about the Exodus from Egypt: “Moses, at the command of the Lord, described their journey through their camps ...” (Numbers 33: 2). And also: “And Moses wrote this law...” (Deuteronomy 31:9).

The theory that Moses wrote the Pentateuch became dominant beginning in the first century BC. It was adhered to by Josephus Flavius and Philo of Alexandria.

Nowadays, this theory is completely rejected. But the New Testament still attributes authorship to Moses. Paul in his letter to the Romans (10:5), quoting from Leviticus, states: “Moses writes about the righteousness of the law: the man who does it will live by it.” And the Gospel of John (5: 46-47) ascribes to Christ the following words: “For if you had believed Moses, you would have believed Me, because he wrote about Me. If you do not believe his Scriptures, how will you believe My words?”

Here we have one example of arbitrary text editing, since the corresponding Greek text uses the word “episteute”. Thus, the evangelist puts into the mouth of Jesus a statement that is completely contrary to the Truth, and this can be proven.

For an example to illustrate this, I will turn to Father De Vaux, director of the Bible School in Jerusalem. He prefaces his 1962 French translation of Genesis with a general introductory chapter to the Pentateuch containing valuable arguments. These arguments contradict the claims of the evangelists regarding the authorship of the said Scripture.

Father De Vaux reminds us that the “tradition of the Jews, received by Christ and his Apostles” was accepted as Truth until the end of the Middle Ages. The only person who protested it was Aben Ezra, who lived in the twelfth century. It was only in the sixteenth century that Karlstadt reasonably noted that Moses could not describe the story of his own death in Deuteronomy (Deuteronomy 34: 5-12). Father De Vaux then cites other critics who refused to accept even partial Mosaic authorship of the Pentateuch. Among others, such works include the work of the father of rhetoric, Richard Simon, entitled “A Critical History of the Old Testament” (Histoire critique du Vieux Testament) and published in 1678. It pointed out chronological inconsistencies, repetitions, confusion of facts in the narratives, and stylistic differences in the Pentateuch. This book had scandalous consequences. R. Simon's style of argumentation was unacceptable for historical books of the late seventeenth century: in those days, the ancient era was very often presented as “recorded by Moses.”

It is easy to imagine how difficult it was to fight a legend supposedly supported by Jesus himself, who, as we have already seen, allegedly supported it in the New Testament. The decisive argument comes from Jean Astruc, the personal physician of King Louis XV. In 1753, he published a work entitled Conjectures sur les Memoires originaux dont il paraоt que Moyse s'est servi pour composer le livre de la Genise, in which especially pointed out the multiplicity of sources that made up the Book of Genesis. Jean Astruc was probably not the first to notice this, but he was the first to have the courage to reveal an extremely important fact: two texts with names derived from the words Yahweh and Elohim, which in these texts called God, are presented literally side by side in Genesis about side. Therefore, the Book of Genesis contains two combined texts. Another explorer, Eichhorn, in 1780-1783. came to a similar conclusion regarding the other four Books. And then Ilgen, in 1798, noticed that one of the texts highlighted by Astruk, where God is called Elohim, in turn, also consists of two parts. Thus, the Pentateuch literally fell apart.

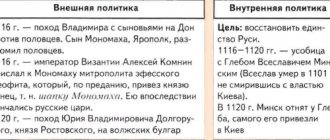

The nineteenth century was marked by even more detailed research. In 1854, the existence of four springs was recognized. They are called the Yahwist Variant, the Elohist Variant, the Deuteronomy Variant, and the Sacerdotal Variant. They were even able to date them:

1. The Yahwist version was dated to the ninth century BC. (written in Judea);

2. The Elohist version most likely arose somewhat later (written in Israel);

3. Some researchers attributed Deuteronomy to the eighth century BC. (E. Jacob), others - by the time of Josiah (Father De Vaux);

4. The Sacerdotal variant dates back to either the period of the exile or the time immediately after the exile - this is the sixth century BC.

Thus, one can see that the process of formation of the text of the Pentateuch stretched over at least three centuries.

However, the problem is not limited to this. In 1941, A. Laud identified three sources in the Yahwist version, four in the Elohist version, six in Deuteronomy, nine in the Sacerdotal version. And this, as Father De Vaux writes, “not counting the additions made by eight different authors.”

In subsequent years, it became clear that “many of the laws contained in the Pentateuch have analogues outside the Bible and that these analogues go back further than the dates indicated in the documents themselves.” And “many of the stories described in the Pentateuch are supposed to have roots other than those from which all these documented narratives are generally believed to have originated; that these roots are more ancient.” This determines “interest in the formation of traditions”, in the process of the emergence of ancient legends.

Such a turn complicates the problem so much that anyone can get lost in its wilds.

The multiplicity of sources leads to numerous repetitions and contradictions. Father De Vaux gives examples of partial repetition of information in the stories about the Flood, the abduction of Joseph, his adventures in Egypt, as well as examples of contradictions such as discrepancies in names referring to the same character, differences in descriptions of important events, etc. .

Thus, the Pentateuch appeared to consist of a whole set of very different legends, more or less successfully combined into a single whole by its authors. These authors combined information from different sources, and sometimes modified the narratives in such a way that the text of the Old Testament seemed holistic and consistent. However, they were never able to completely eliminate numerous improbabilities and contradictions. All this led our contemporaries to the idea of the need to conduct a deep, objective study of primary sources.

In a practical analysis of the Pentateuch, it appears as perhaps the most obvious example of a text altered by human hand. Edits to the text were made at different periods in the history of the Jewish people, information about which was drawn from oral tradition and texts passed down from generation to generation. The history of this people began to be recorded in the tenth or ninth century with the emergence of the Yahwist version, which records its very origins. Israel's purpose and destiny are presented here as "an integral part of God's Great Destiny for mankind" (Father De Vaux). And this “recording of history” was completed in the sixth century BC. The Sacerdotal version, in which all dates and genealogical branches are listed down to the smallest detail[16].

Father De Vaux writes that “Several narratives from this tradition indicate a desire for lawmaking - God's rest on the Sabbath, i.e. on Saturday, after the completion of the Creation of the world; union with Noah; union with Abraham and circumcision; the purchase of the Makpela Cave, which gave the spiritual fathers land in Canaan.” We must not forget that the Sacerdotal version dates from the time of the exile to Babylon and the return to Palestine, which began in 538 BC. Consequently, here we have a mixture of religious and purely political problems.

As for the Book of Genesis, the presence of three sources is firmly established. In a commentary to his own translation of this Book, Father De Vaux classified the individual parts according to the sources from which the modern text of Genesis originates. Having such data in hand, you can accurately assess the contribution of various sources to the writing of any of the chapters. In the texts describing the Creation of the world, the Flood, as well as the period from the Flood to Abraham, the narrative of which occupies the first eleven chapters of Genesis, we see a consistent alternation in the text of the Bible of sections from the Yahwist and Sacerdotal sources. The Elohist variant is not present in the first eleven chapters. Thus, the fact of the simultaneous use of Yahwist and Sacerdotal sources is quite obvious. In the first five chapters, which deal with the events that occurred from the Creation of the world to Noah, the structure of the text is very simple: here passages from the Yahwist and Sacerdotal sources successively alternate. As for the Flood (especially chapters 7 and 8), here the text of each of the sources is shortened and reduced to very short passages, sometimes even to one sentence. As a result, in the English text, which occupies just over a hundred lines, passages from both sources alternate seventeen times. This is precisely what determines all the improbabilities and contradictions that we notice when reading the modern version of the text. To demonstrate this, we present a table that shows the source distribution scheme.

Table of distribution of Yahwist and Sacerdotal texts in chapters 1-11 of Genesis

The first digit indicates the chapter. The second number indicates the number of phrases, sometimes divided into two parts, indicated by the letters "a" and "b". Letter designations: I - indicates the Yahwist text, S - indicates the Sacerdotal text. Example. The first row of the table indicates the following: from the first phrase of chapter 1 to phrase 4a of chapter 2, the text of modern editions of the Bible is the text of the Sacerdotal source.

| from the head | phrases | up to chapter | phrases | text |

| 4a | WITH | |||

| 4b | I | |||

| WITH | ||||

| I | ||||

| WITH | ||||

| I | ||||

| WITH | ||||

| I (adapted) | ||||

| WITH | ||||

| I | ||||

| 16a | WITH | |||

| 16b | I | |||

| WITH | ||||

| I | ||||

| 2a | WITH | |||

| 2b | I | |||

| WITH | ||||

| I | ||||

| 13a | WITH | |||

| 13b | I | |||

| WITH | ||||

| I | ||||

| WITH | ||||

| I | ||||

| WITH | ||||

| I | ||||

| WITH | ||||

| I | ||||

| WITH | ||||

| I | ||||

| WITH | ||||

| Is it possible to find a clearer way to show exactly how people managed to “shuffle” the Bible Scriptures? |

Historical books

From these Books we learn about the history of the Jewish people - from the time of their arrival in the Promised Land, which apparently took place at the end of the thirteenth century BC, until their exile in Babylon in the sixth century BC.

A common thread running through all these Books is the so-called idea of a “national event,” presented as the fulfillment of the Word of God. However, historical accuracy in the narrative is practically not observed. For example, the Book of Joshua is primarily intended to serve theological purposes. Taking this into account, E. Jacob points out the obvious contradiction between the data of archaeological excavations and the texts when it comes to the alleged destruction of Jericho and Ai.

The Book of Judges of Israel tells how the chosen people defended themselves from the enemies that surrounded them, as well as the support given to them by God. This Book was revised several times, as Father A. Lefebvre notes with all objectivity in his preface to the Crampon Bible.

Evidence of this are various prefaces, as well as appendices to its text. The story of Ruth is placed there as one of the narratives of the Book of Judges.

The Book of Samuel and the two Books of Kings are primarily accounts of the lives of Samuel, Saul, David, and Solomon. Their value as historical documents is debatable. From this point of view, E. Jacob finds numerous errors in it, since information about the same event is described in two or even three different versions. The images of the Prophets Elijah, Elisha and Isaiah are also given here, and all sorts of legends are mixed with historical facts. As for other commentators, for example, A. Lefebvre, for him “the historical value of these Books is fundamental.”

The First and Second Books of Chronicles (Chronicles), the Book of Ezra, and the Book of Nehemiah were written by the same author, a so-called “chronicler,” working in the fourth century BC. He reproduces the whole history again - from the Creation of the world up to the fourth century, although his genealogical tables end only with David. In fact, he uses primarily the Book of Samuel and the Book of Kings, “mechanically rewriting them and not taking into account the contradictions in the facts” (E. Jacob). But at the same time, he still supplements them with accurate information, confirmed by the results of archaeological finds.

In these works, the authors sought to adapt history to the needs of theology. E. Jacob notes that the author “sometimes writes history in accordance with theological criteria.”

Further: “To explain the fact of the long and prosperous reign of King Manasseh, which reached the point of sacrilege in the persecution of the Jews, the author puts forward as a postulate the assumption that during his stay in Assyria the king accepted the religion of the One God (II Chronicles, 33: 10-16 ), although this is not mentioned in any other Biblical or any other sources.” The books of Ezra and Nehemiah have been severely criticized because of the abundance of ambiguities in them. However, it should be noted that the period they describe is the fourth century BC. - itself is not very well known, only a very small number of documentary sources that do not belong to the Biblical category have survived about it.

The books of Tobit, Judith and Esther are also classified as historical. However, their authors treat history very freely - historical names are changed, characters and events are fictitious, and all this is done in the best religious traditions. In the end, all these narratives are nothing more than moralizing, flavored with fictitious and distorted facts.

The books of the Maccabees are narratives of a completely different order. They present one version of the chronology of events that actually took place in the second century BC. The information contained here allows us to most accurately reproduce the historical picture of this period. It is for this reason that their stories are of great value.

What has been said here allows us to conclude that the collection of Scriptures under the general heading of “historical Books” is replete with contradictions. Their authors handle historical facts in two ways - both objectively (in the modern sense, scientifically) and willfully.

Books of the Prophets

Under this heading we find the sermons of various prophets, to whom a special place is given in the Old Testament. They stand apart from such early great Prophets as Moses, Samuel, Elijah, and Elisha, whose teachings are mentioned in other Scriptures. The books of the Prophets cover the period from the eighth to the second centuries BC.

In the eighth century BC. The Books of Amos, Hosea, Isaiah and Micah appeared. Amos is famous for his condemnation of social injustice. Hosea is best known for being forced to take a pagan harlot as his wife. By doing this he betrayed his religion and because of this he experienced bodily torment - like God suffering because of the moral and religious failure of His people, but still rewarding them with His love. Isaiah showed himself to be a political personality: he communicates with kings and rises above current events, he is a great Prophet. In addition to the works he personally wrote, his disciples continued to publish his prophetic oracles until the third century BC. They sounded a protest against injustice and lawlessness, fear of God's Judgment, and calls for liberation both during the exile and later, upon the return of the Jews to Palestine. There is no doubt that in the second and third Books of Isaiah, prophetic purposes and intentions are supported by political considerations. The preaching of Micah, a contemporary of Isaiah, carries similar ideas.

Seventh century BC was marked by the preaching of Zephaniah, Jeremiah, Nahum and Habakkuk. Jeremiah became a martyr. His prophecies were collected by Baruch, who, according to one version, is the author of the Book of Lamentations.

The period of Babylonian exile in the early sixth century BC. gave impetus to intense prophetic activity. Ezekiel occupies an important place here as a comforter to his brothers, giving them hope. His visions are also famous. And the Book of Obadiah talks about the suffering and sorrows of conquered Jerusalem.

After the exile, which ended in 538 BC, prophetic activity resumed with the appearance of Haggai and Zechariah, who convincingly called for the restoration of the Temple. When the restoration was completed, the Scriptures appeared under the name of Malachi. They contain various spiritual prophecies.

I wonder why the Book of Jonah is classified among the Books of the Prophets? After all, judging by the text that is placed in the Old Testament, it does not contain anything that he actually said. Jonah is a narrative from which one fundamental conclusion emerges: the necessity of obedience to the will of God.

The Book of Daniel was written in three languages—Hebrew, Aramaic, and Greek. Christian commentators believe that, from a historical point of view, this is a “tumultuous” Apocalypse. It is possible that this work dates back to the Maccabean period, that is, the second century BC. In times of “unbearable desolation and misfortune,” the author of this Scripture sought to support the faith of his compatriots, convincing them of the nearness of deliverance (E. Jacob).

Books of Poetry and Wisdom

The unity of the literary style of this collection among all the Books of the Bible is a generally recognized fact.

Of these, first of all, it is necessary to note the Psalter - the greatest monument of Hebrew poetry. Many of the Psalms were composed by David, the rest by the priests and Levites. They contain praises, prayers and reflections. The Psalter was used during religious services.

The Book of Job, which is a book of wisdom and supreme piety, possibly dates back to 400-500 BC.

Author of Lamentations, about the fall of Jerusalem in the early sixth century B.C. it could well have been Jeremiah himself.

We, again, must mention the Song of Songs of Solomon - allegorical songs, mainly chanting Divine love, as well as the Book of Proverbs of Solomon - a collection of sayings of Solomon and other court sages and the Book of Ecclesiastes, or Preacher, in which discussions are held about Earthly happiness and wisdom.

⇐ Previous2Next ⇒

Recommended pages: