The Edict of Milan, written by Constantine the Great in 313, ended the brutal persecution of Christians. The Christian Church came under the protection of the state.

Changes in social activities and normative culture followed, and this was very good for the early Christians. Before this, Christians were subjected to terrible persecution; they had to pray underground in order to avoid dangers from society, pagan and Jewish organizations. This lasted for the first three centuries.

What is a monastery?

A monastery is a home for monks: their family, apartment and fortress. This is a tiny city with its own way of life and regulations. This is a settlement where everyone is united by one thing - life for God and the unceasing memory of Him. This is a monastery in which monks, without denying modern state laws, live for the sake of spiritual laws.

Monasteries can be located anywhere (within the city, next to it, or far from any populated area - for example, on rocks).

Monasteries can be of different sizes: from a tiny courtyard with several monks to a large Lavra, where the brethren can number hundreds of monks.

Monasteries can be male or female. Monasteries can have, in fact, a variety of external features, architecture and forms, but they all have one thing in common: this is a place where people gather who have left the world in spirit. Those who left everything in the world - things, attachments, earthly claims - leaving there, in essence, their former selves and thereby finding a new selves.

For monks, the monastery is a fence and support in their New Life, which ideally should be equal to the angels.

See also: Why do people join a monastery and who are monks?

For “laity”, a monastery is an opportunity to come into contact with a “different” world: to see with their own eyes a life built not according to the principles and aspirations of secular existence, but according to the principles of spiritual, Gospel life.

After all, what is a monastery in essence? This is a piece of the heavenly, mountainous world on our earth. A place where the Holy Spirit breathes and sanctifies everyone who enters and, even more so, who lives there.

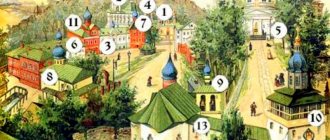

Mozhaisk Luzhetsky Ferapontov Monastery.

Rules and regulations in monastic life

Later, the Church developed rules and various regulations that united monks into groups for the consistent expression of Christianity. The first Christian monastic movement was born in the deserts around Israel.

There are many conflicting stories about this, but there is almost no evidence. The first monks became famous for their special approach to the Christian faith, which was approved by the local society. They abandoned all comforts and devoted themselves entirely to spiritual life, consisting of prayers, social assistance to people, teaching and spreading the Christian faith. There were not only men's monasteries, but also a large number of women's monasteries. The history of some monasteries goes back centuries. In the movement of Christian monasticism, not only men, but also women could use their personal talents.

How do they live in the monastery?

Each monastery may have its own order of life (in other words, the charter). In some monasteries he is stricter, in others he is “softer”. Within the same monastery, different monks lead different levels of prayer and ascetic life - each according to his strength, each according to his calling.

Despite all the differences that are possible in the structure of monastic life, all monasteries are united by one thing: prayer and divine services occupy a central place in the daily routine and life of the monks. In monasteries, unlike non-monastic, “parish” churches, a full daily cycle of services is held, and the services themselves last longer.

In general terms, a day in a monastery might look like this:

- Five or six o'clock in the morning: the beginning of morning services. Their duration depends on the day or charter of the monastery. On ordinary days, morning services may end at nine; on holidays, they may continue until noon.

- After morning service: breakfast, meal

- Then: a short rest and a time of obedience (obedience is an integral part of monastic life, for idleness is the main enemy of a monk. During obedience, someone monitors the cleanliness of the territory, someone looks after the garden, someone carries out carpentry work, someone... then he works in a stable - and so on).

- In the middle of the day: meal (lunch), then - continuation of obediences.

- At approximately four or five o'clock in the afternoon, evening services begin, which can also last three hours or longer, depending on the day.

- After the evening service - meal, short rest

- Before going to bed - a general or cell prayer rule.

Famous Holy Monks and Nuns

Some of the first monks are recorded in the Holy Scriptures. One of these righteous people was Saint Anthony of the Desert, born approximately 251–256. For several years he lived in the deserts of Egypt. Later he gathered his disciples into a community of hermits.

Their lives differed in many ways from later monastic communities. Another famous early hermit, Amma Syncletica of Alexandria, who lived around 270 - 350, went into the desert after the death of her parents. There she settled in a crypt. Later, other local women joined her.

A monastery was founded in Tabennisi by Saint Pachomius between the 3rd and 4th centuries. Pachomius began to be called "Abba", later this word was transformed into the word "abbot". Pachomius made a great contribution to the development of communal monasticism.

In the 4th century, monasticism spread to Europe. Many other monasteries were founded in the Egyptian style. A famous monk of the 5th–6th centuries was Saint Benedict of Nursia. He established monastic rules that became the standard for all Christian monasticism. But they were relatively flexible and did not require lifelong commitment and permanence. In the 13th century, mendicant (begging) monks appeared. This order was established by Francis of Assisi, who promoted poverty as a holy way of life.

The same mendicant monks were the Dominicans, who tried to return heretics to the Church. Mendicant orders were often criticized by society for promoting stoicism, alienation, and arrogance. Those men and women who joined the monks believed that in this way they would gain salvation, freedom and victory over the world.

For this they sacrificed everything: the benefits and pleasures of worldly life. For them, the ideal was a martyr striving for the Lord. But historically, supporters of the monastic movement have had many victims. The monks valued celibacy, following the example of Paul and the prayer life of Jesus Christ. This was the ultimate role model for them.

There were also militant orders among the monks. The most famous of them was the Templar Order. He and others like him began to appear after the First Crusade. The inspiration was Bernard of Clarivon. The knightly monastic class of these orders consisted of celibate and mostly uneducated members. The Templars were the first to introduce banking methods of lending and checks to ensure the collection of funds for pilgrimages to the Holy Land.

Who lives in the monastery?

Those who live in monasteries are called inhabitants of the monastery. This:

Actually the monks

Unlike pre-revolutionary times, now there are no rules about how many monks there should or should not be in a monastery. Life determines everything.

Monks are the “spiritual backbone” of any monastery. We wrote about what degrees of monasticism there are and about monasticism in general here.

Novices

Who are the novices? These are people who are preparing to become monks, but according to the abbot, they are not yet ready for this. At the same time, the monastery already bears spiritual responsibility for the novice.

Monks from Holy Mount Athos, first half of the 20th century. Second from left: Venerable Silouan of Athos.

Workers

Who are the workers? Roughly speaking, the same novices, only at the very beginning of their journey. They live with everyone in the same way, perform obediences, and work in the same way.

At the time of entering the monastery, a trudnik is just as sure that he is destined for monasticism, but, as practice shows: since not every novice eventually becomes a monk, then among trudniks this percentage is even smaller. The first inspiration passes, and the person already understands that he had a completely wrong idea about monasticism or his powers - and returns to the world. Or he goes to try himself in another monastery.

Guests, pilgrims

These are even more “temporary” “guests” for the monastery. Although there were cases that it was from a random “guest” who found himself in the monastery out of need, or a pilgrim, that a monk was eventually born.

The simple life of the first Christian hermits

But later, after Constantine, permissiveness and favoritism began among Christian leaders and the laity. Believers began to worry about the church's internal immorality. They were not satisfied with the abuses and vices in the church environment. Possessing privileges, the religious leaders were full of arrogance, and they did not disdain corruption. Therefore, many ordinary Christians began to look for another purist environment where they could observe their spirituality.

These people were not part-time Christians. They renounced all worldly goods and comforts and devoted themselves to spiritual work. The monastic lifestyle of the first hermits was very simple. But with each century it became more and more intricate and diverse. The first monks and nuns lived in caves, swamps, deserts, cemeteries, high in the mountains and in other inaccessible, remote corners of the earth. They were driven only by God's calling.

What kind of buildings are there in monasteries?

In fact, the only thing that must be required in a monastery is at least one temple and a house where the monks will live. The room in which a monk lives is called a cell.

Otherwise, everything depends on the size of the monastery and its location.

The small monastery of St. George in Bulgarian Pomorie.

But let's take an “average” idea of the monastery. It could have such buildings and structures.

- The territory itself

(it is fenced. In Russia, monasteries used to play the role of fortresses, and therefore their walls were stone, strong and high. For example, the Holy Trinity Lavra of St. Sergius held the siege of the Poles for several months, and they were never able to take it). - Central temple

(cathedral). The place where either the main or, with few exceptions, all services take place. - Another temple

(in large monasteries there may be two, three, or as many as you like). As a rule, it is used rarely - on the days of the largest holidays and on other days that are significant for the monastery. - Fraternal Corps

. This is the house where the cells are located - the rooms of monks and novices. - Refectory

(dining room). Sometimes it is located in a residential, fraternal, building. - Guest House.

Maybe very small, or maybe a large multi-story building. There are separate guest houses for monks and bishops from other monasteries. - Canteen for pilgrims.

- Church shop -

candles, icons, books, church utensils for sale. - Other buildings.

They can house anything - from a Sunday school to a monastery publishing house.

Bulgaria. Pomorie. Monastery of St. St. George the Victorious. Typical territory of a small monastery. On the right is the fraternal building.

Chapter 3. Monasteries and monasticism

In the 19th, and especially at the beginning of the 20th centuries. The financial situation of the monasteries improved significantly. Cash benefits from the treasury increased, the monasteries again began to turn into large landowners, thanks to which they were able to expand economic activity, which in large monasteries acquired an entrepreneurial character.

By decree of Paul I of December 18, 1797, 30 acres of pasture land were demarcated for each monastery, and the monasteries received the right to set up mills and establish ponds for fish breeding86. The maintenance of regular monasteries has been increased. They began to receive an annual allowance of 300 rubles from the treasury. ordinary monasteries. By decree of Alexander I of June 8, 1805, monasteries were able to receive uninhabited plots of land as a gift or by will, but the permission of the emperor was required to purchase land87. The decree of May 24, 1810 allowed monasteries to freely acquire uninhabited lands by purchase88.

During the reign of Nicholas I, monastic land ownership expanded significantly due to grants from the emperor of various lands. In 1838, each monastery was allocated free forest dachas in the amount of 50 to 150 acres. At the same time, the largest monasteries received forest dachas that significantly exceeded the specified norms; for example, the Trinity-Sergius Lavra was allocated 1,250 acres. In addition, Nicholas I, by decree of September 6, 1838, ordered that 100 dessiatines be allocated to newly established monasteries89, while land began to be allocated to some previously existing monasteries. Only in 1836–1841. 25 thousand dessiatines were transferred free of charge to 170 monasteries (16 thousand dessiatines of forest and 9 thousand dessiatines of arable land and hayfields). Monasteries that were not allocated land received monetary compensation based on the income of the land due to them90.

In the second half of the 19th century. Along with royal grants, the monasteries expanded their land ownership through purchases. In 1874, there were 540 land-owning monasteries, who owned a total of 250 thousand acres of land. 200 of them were large landowners, with an average of 1,232 dessiatines each91. Most of the monastery lands were occupied by forest, which the monasteries by law did not have the right to sell, but could only use it for their own needs: for construction, for heating, etc. In 1887, 697 monasteries had 496,308 acres of land (129,743 acres of arable land, 86,149 dessiatines of hayfields, 249,817 dessiatines of forest, 30,599 dessiatines of other land) and 75,900 dessiatines of inconvenient land. On average, there were 709 acres per monastery. Among them stood out large landowners who owned thousands and tens of thousands of dessiatines of various land plots92.

At the end of the 19th – beginning of the 20th centuries. Monastic land ownership increased not only due to purchases, but also through continued royal grants. Only in 1916, Nicholas II ordered the donation of 3,609 acres of arable land and forests from the state land fund to monasteries and bishops' houses93.

In 1917, there were 1,257 laurels, monasteries, monasteries, monasteries and bishops' houses, which in total owned 1,159,875 acres of land (an average of 923 acres per property). Among them, 13 monasteries each owned over 10 thousand dessiatines: Solovetsky, which had 66.7 thousand dessiatines (however, up to 90% of the inconvenient - low-growing forest, tundra and swamps), Kozheozersky - 17.6 thousand, Murmansk Alekseevsky – 10 thousand, Mogilev Uspensky – 13.9 thousand, Troitsko-Zelenetsky – 19 thousand, Sarovsky – 26 thousand, Grigorievsko-Borisoglebskaya Hermitage – 25 thousand, Alexander Nevsky Lavra – 13 thousand, Seraphim-Ponetaevsky – 13 ,9 thousand, Novo-Nyametsky Voznesensky in Bezsarabia - 12 thousand, Grigorievsko-Bizyukovsky in the Kherson province - 26 thousand, Uspensky Amursky - 20 thousand, Kamchatka Alekseevsky - 10 thousand, Temnikovskaya Uspenskaya Hermitage - 24 thousand. However, in fairness, it should be said that the 13 monasteries listed above were located primarily on the outskirts of the Russian Empire, with a large reserve of still undeveloped, or even inconvenient, lands. Smaller in size, but more valuable in terms of quality of land, were owned by famous monasteries, located mainly in provinces convenient for agriculture. The Kiev Pechersk Lavra had 6.5 thousand dessiatines, Nilova Monastery - 4.7 thousand, Anthony-Siysky Monastery - 2.7 thousand, Seraphim-Diveevsky - 2.4 thousand, Valaam - 3 thousand, Trinity-Sergius Lavra – 2.1 thousand, Kirillo-Belozersky Monastery – 2.3 thousand, Optina Pustyn – 1.2 thousand. In 1917, 1 million 160 acres of land were taken away from the monasteries and nationalized94.

In the XIX – early XX centuries. In addition to land grants, the monasteries systematically received cash payments from the treasury. Since 1839, the treasury began to issue annual additional assistance in the amount of 148 thousand rubles. Since 1842, this payment has been increased to 260 thousand rubles. In addition, one-time cash benefits were also given to the poorest monasteries95. The monasteries used free government servants, who were recruited from state peasants and were obliged to serve for 25 years, after which they returned to their rural society. In 1865, this duty was removed from the peasants, and 186.2 thousand rubles were paid annually to the monasteries in the form of compensation. for hiring servants.

The monasteries received significant donations from private individuals - cash, as well as liturgical utensils: icons with gilded frames, vestments decorated with gold and precious stones, liturgical vessels.

Donors cast bells for monasteries, built monastery churches at their own expense, and ordered iconostases with expensive carvings and gilding. Countess A.A. Orlova-Chesmenskaya, in her will in 1848, donated 1.7 million rubles to 340 monasteries. In addition, she donated valuable items to the Pochaev Lavra, Solovetsky and Yuriev monasteries96. In 1869, 300 thousand rubles were received from donors. Moscow Ioannovsky Convent, 98 thousand rubles. 890 acres of land at the Znamensky convent in the Novgorod province97. In 1859, the “Society for Assistance to the Poorest Churches and Monasteries”98 was founded.

In their domains, the monasteries carried out highly efficient arable farming, vegetable gardening, horticulture, cattle breeding, poultry farming, and beekeeping. The Valaam monastery had an extensive gardening and vegetable garden. In the harsh northern conditions, various varieties of apples were grown here, for which the monastery received prizes at agricultural exhibitions. There was a fish factory at the monastery, where valuable species of fish were bred. There was a market-oriented dairy farm, a well-equipped horse yard with 70 working and riding horses; It had its own carpentry, metalworking, cooperage, pottery and icon-painting workshops, candle making, tar, brick, stone cutting, lime and sawmill factories, a mechanical workshop with lathes, and even had its own photographic workshop. Located in an exceptionally picturesque area, the monastery attracted famous landscape artists (for example, A.I. Kuindzhi, V.D. Polenov, I.I. Shishkin visited it several times).

An extensive and varied economy was carried out in the Solovetsky Monastery. The monastery had a lard-making factory, a candle factory, a pottery factory, a brick factory, a sawmill, a tar factory, a foundry, a mechanical factory, a tannery, jewelry, carpentry, metalworking, and carriage workshops. The island had a canal system that provided regular water supply. The monastery had a shipyard where screw steamships and small sailing ships were built. Important profitable sectors of his economy were “fish and animal” trades. Every year, from 700 to 800 young men came to the monastery under vows to work for the benefit of the monastery and acquire skills in some craft; the monastery provided them with clothing and food.

To run their households, the monasteries also used hired labor. Thus, in 1889, in 476 monasteries there were 26 thousand people working for hire99.

A significant part of the monastery lands, as well as the mills, trading shops, piers and other “ quitrent articles ” belonging to the monasteries, were leased. According to the Holy Synod, as of January 1, 1917, the monasteries leased out 276 manor arable and hay lands100.

In large cities, monasteries received considerable income from monastic cemeteries. Burial places in the cemeteries of the Alexander Nevsky monasteries in St. Petersburg, Novodevichy, Alekseevsky, Donskoy in Moscow and others were assessed at the beginning of the 20th century. in the amount of 50 to 500 rubles, in addition, the burial itself cost from 10 to 50 rubles. Significant sums were charged for “eternal remembrance” (for example, the same Alexander Nevsky Lavra charged up to 1000 rubles) and for the construction of monuments.

The monasteries were also involved in financial activities, lending money at interest. When private banks with higher interest rates on deposits appeared in Russia after 1861, the monasteries began to invest their money in these banks.

Measures were taken to record and control the monetary deposits of monasteries and other religious institutions. In 1883, a circular from the Synod followed, ordering “institutions and institutions under the jurisdiction of the Spiritual Department, under no circumstances, to place amounts to increase interest in private, public, city and other banks.” Demand deposits in banks must be returned immediately, term deposits must be returned before expiration and exchanged for government interest-bearing securities. From now on, funds from religious institutions should be placed in the State Bank and used to purchase only government interest-bearing securities101.

In 1913, the amount of monastery deposits in banks amounted to 65.6 million rubles. At the end of the 19th century. monasteries began to invest their funds in city apartment buildings. For example, in 1903 in St. Petersburg there were 266 apartment buildings and 40 commercial warehouses that belonged to monasteries and churches, which rented them out. In Moscow, at the same time, the monasteries alone owned 146 apartment buildings; in addition, they had 32 farmsteads, inns, trading warehouses, and extensive vegetable gardens both within the city and outside it. In Kyiv, churches and monasteries owned 114 houses; some of them were rented out.

DI. Rostislavov, in a special study on the property status of monasteries, lists up to 20 other sources of income for monasteries: donations for the remembrance of the dead, “circle collection”, “purse collection”, “prayer service”, “prosphora”, from the sale of candles and lamp oil, from chapels, from godparents moves, printing and publishing. From the sale of lithographed paintings of spiritual content, from areas for fairs and markets on the monastery land, from shops, etc.

The largest monasteries, such as Solovetsky and Valaam, Trinity-Sergius and Kiev-Pechersk Lavra annually attracted tens and hundreds of thousands of pilgrims, which also brought considerable income to these monasteries. During the holidays, with a large crowd of pilgrims, there was a brisk trade in crosses, icons, incense, candles, pictures and books of spiritual content, as well as food supplies. In the Trinity-Sergius and Kiev-Pechersk Lavra, up to 300 thousand pilgrims visited each year. Near Kursk, from 80 to 120 thousand pilgrims gathered in the procession during the transfer of the icon of the Mother of God. (Let us remember the famous painting by I.E. Repin “Religious procession in the Kursk province.”) A large crowd of people also caused the service sector and well-established trade in them. It should be noted that such famous fairs as Irbitskaya in Siberia and Makaryevskaya (Nizhny Novgorod) arose near monasteries.

Usually, each monastery had its own shrine: a particularly revered icon or the relics of a saint (usually the founder of the monastery). A mug for collecting money was placed near them. The commercial spirit offended the feelings of believers and caused numerous criticisms in the press of that time.

Statisticians constantly complained about the incompleteness of information about the income of monasteries. But even incomplete data indicate a steady increase in these incomes, especially in post-reform times and at the beginning of the 20th century: in 1861 - 316 thousand rubles, in 1871 - 648 thousand, in 1881 - 1781 thousand. , in 1893 - 3535 thousand and in 1909 - 20.2 million rubles.

Contemporaries and subsequently historians wrote a lot about the “riches” of Russian Orthodox monasteries and the luxurious life of their abbots. Thus, in the “Church Bulletin” for 1875 (No. 117) it was reported: “In the temples of the angelic order, abundance and contentment are in full swing. Soft, magnificent furniture, Persian carpets, luxurious pillows on the sofas, embroidered with wool with images of the animal and plant kingdoms on them; There are blooming flora on the windows, sweet and rich dishes at the table, and an excellent dessert after the table.” Professor of the St. Petersburg Theological Academy D.I. Rostislavov, in his anonymously published “Experience in Research on the Property and Income of Our Monasteries” in 1876, cited numerous facts about the life of monastics in the most famous and wealthy monasteries. The publication of the book was a sensation and caused an explosion of dissatisfaction among monastics with the revealing facts. Thus, the book reported: “For the rare abbot there is not a couple or three horses with a decent carriage, even a carriage or carriage, to go somewhere... The decoration of the abbot’s chambers is magnificent: parquet floors, expensive carpets, furniture made of mahogany and walnut, upholstered valuable or silk materials." Rostislavov talks about the impression that the sacristy of the Trinity-Sergius Lavra made on August Haxhausen. Seeing in it numerous church vessels, cups, censers, miters and staffs made of pure gold and decorated with precious stones, altar Gospels in gold bindings and other objects of “incalculable value,” Haxhausen wrote: “They surpass everything that can be seen in the rest of Russia and throughout Europe, excluding Rome."102.

However, a conclusion about the fabulous riches of the monasteries cannot be drawn only from such large monasteries as Solovetsky, Valaam, Spaso-Evfimievsky, and even more so from the Trinity-Sergius, Kiev-Pechersk and Alexander Nevsky Lavra, which have always enjoyed the special attention and favor of the great princes and kings and emperors and accumulated their wealth for centuries.

In reality, there were few rich monasteries. The vast majority were small, poor monasteries. Usually they were located in remote, remote places, having insufficient land, they lived meagerly, subsisting on small handicrafts and even alms.

How many monasteries are there in Russia?

The number of Orthodox monasteries in Russia is constantly growing. Now there are more than 800 of them. In 1986 there were less than twenty.

The main monastery in Russia is the Holy Trinity Sergius Lavra.

One of the oldest monasteries in Russia is the Nikitsky Monastery in Pereslavl-Zalessky.

The contribution of Christian monasticism to history

The historical contribution of Christian monasticism lies in the survival of education and culture after the fall of the Western Roman Empire. It also perpetuated early Greco-Roman Christian manuscripts by preserving them in monastic scriptoria. The monks were engaged in the development of important medicines and the creation of elementary pharmacies, thereby making a great contribution to the development of medicine and pharmaceuticals. Thanks to agricultural production organized in monasteries, Western capitalism with the division of labor was born. Great successes were achieved in the visual arts, music, and cooking. Monasteries maintained social stability in Western and Eastern Europe.

Solovki. Why does a monastery need a fortress?

They will gradually rise straight from the depths of the sea... First, gilded crosses, domes, gray hipped roofs, and then powerful walls of the Solovetsky Fortress, built from huge erratic (glacial) boulders, built in 1582-1594. under the leadership of monk Tryphon, a native of the Pomeranian village of Nenoksa.

Wow... Ma-hee-na!

Judge for yourself. The perimeter of the fortress exceeds a kilometer, the height of the ground part of its walls ranges from 8 to 11 meters, the thickness of the masonry at the base reaches six. Eight towers rise above the walls, reaching 30 meters at the tops of the tents and protruding far beyond the line of the walls, thereby providing the possibility of powerful flanking shelling. The Solovetsky Fortress became a miracle of fortification art.

And here is such a miracle - in the middle of the ocean sea? For what?

If you think about it, for protection and defense. But from whom? From a foreign enemy? As an option, this hypothesis can be considered. Moreover, in the long, centuries-old history of the monastery there are individual episodes of resistance to armed foreign aggression.

At the height of the Livonian War, in 1571, an enemy flotilla of Swedish, Dutch and Hamburg ships appeared near Solovki. From the seriously frightened monastery, a letter is urgently sent to Moscow with a request for protection. But only seven years later the king was able to provide all possible assistance and send a small team consisting of a governor, ten archers and four gunners. At the same time, the first fortress began to be built around the monastery - a wooden fort with towers - and ninety-five archers were recruited to defend it. However, already in 1637, due to the reduced danger of an enemy attack, this “numerous” army was abolished, and the defense of Pomerania passed completely into the hands of the abbot. Well, he (and all the brothers, of course) by that time was already sitting in a stone fortress and was not afraid of the adversary.

True, in the spring of 1854 the islanders’ confidence in their complete safety was called into question. At the height of the Crimean War, a messenger was first sent from Arkhangelsk to Solovki with a message about the danger of an enemy attack, and then more significant assistance in the amount of eight cannons with shells. And on time. Already on July 7, the monastery came under intense fire from two English sixty-gun frigates. About one thousand eight hundred cannonballs and bombs were fired at the fortress, which would have been enough to destroy several cities. But after a nine-hour cannonade, which did not lead to any serious destruction, the British were forced to leave the monastery alone. None of the defenders were hurt...

AND? Because of several episodes of the Livonian War and the Crimean Campaign, was it worth making a fence?

Both in my inexperienced opinion and from a military point of view, the construction of a powerful defensive fortress was clearly unjustified. The sea is not dry land, where there is only one road and forests... Forests... I put a little house at the crossroads of the fortress and that’s it. Until the enemy takes it, there is no way further into the interior of the country. Neither heavy cavalry nor field artillery cannons can be carried through forests and swamps. So, let's go for the assault! And the sea... It’s all just a road. The helm turned left and right a couple of points and went past the islands where it needed to be.

But, if the fortress is not from a foreign enemy... If the defensive structure is not “from someone”... Then, maybe, “for something”? Exactly. It's already warmer.

Especially if you remember that boulder walls and towers, unprecedented at that time, were erected, albeit by order of Ivan IV, but... with the help and at the expense of the monastery itself. The monastery itself! This means that he was the person interested in the construction of the fortress in the first place. Which is actually not surprising. The brothers had something to protect.

Well, for example, the church sacristy. A repository of monastic values, in other words. The monastery had a noble one. After all, before Catherine’s Decree of 1764, the Solovetsky monastery was a major owner. The income from its proper use was significant. Salt pans, fishing grounds, catching sea animals and river pearls - all this brought a lot of money into the monastery treasury.

And there have always been pilgrims who wanted to touch the Solovetsky shrines. Both before the Decree and after it. Just like donations and contributions made not only by ordinary people, but also by patriarchs, princes, nobles... Even kings! All of them, in the hope of atonement for their misdeeds and sins, generously donated money and things to the monastery. Ivan IV especially showered the monastery with gifts. In 1562, by his order, a golden altar cross was made in the Kremlin workshops to be given to Solovki for the health of the princes Ivan and Fyodor. There were also watches, crosses, furs, precious fabrics, a thousand rubles and “a lot of silver utensils.”

It is not surprising that in the second half of the 19th century, the treasures of the monastery were already valued at ten million rubles, and in the two-story sacristy, which by that time had an area of 445 square meters, sets of gold and silver dishes, gilded bowls, dishes, goblets were stored... And so on, so on... Naturally, it is simply impossible to list everything that was in the sacristy of the Solovetsky Monastery. But it’s probably worth briefly talking about some of the most interesting things.

Among the most ancient objects collected here were: a carved cross made of walrus tusk, a wooden chalice (chalice) of St. Zosimas, a small stone bell and an iron riveted to it. Cast gold crosses (one of them weighed 1064 grams), invested by Ivan the Terrible. Silver ladles from the era of Peter I. Church vestments, sewn from amazingly beautiful expensive fabrics: axamite, velvet, brocade, satin...

Some of the items preserved in the sacristy did not have a religious purpose, but were of enormous historical and artistic value. For example, a broadsword in a silver frame with precious stones, which belonged to the famous Russian military leader of the early 17th century, Prince M.V. Skopin-Shuisky. Or an amazing carved openwork bone mug with 58 portrait images of Russian tsars and princes, made in 1774 by the famous bone carver Osip Dudin, a native of Kholmogory...

The collection of ancient manuscripts and early printed books was of extraordinary historical and cultural value: the Gospel of the 14th century, written on parchment, handwritten Gospels of the 16th century (one of them was deposited in the monastery in 1613 by Prince D.M. Pozharsky), handwritten, donated by Ivan IV, “ Apostolic Rules" and "History of the Jewish War" by Josephus...

True, now on Solovki itself there are small, very small crumbs left of this wealth.

But when, how and why the monastery lost its wealth... That's a completely different story. _________________________ Photographs from the websites www.anatol.org, www.fotopotom.ru were used as illustrations for the text of the article.

Tags: Solovki, Russian Empire, fortress, monastery, history