The first Russian saints

Although chronologically Equal-to-the-Apostles Olga and Vladimir lived earlier, the first to be canonized in Rus' were their descendants Boris and Gleb. After the death of Prince Vladimir in 1015, civil strife broke out in Rus'. His son Svyatopolk decided to eliminate all his brothers in order to rule the state alone. For his cruelty, the prince received the nickname Damned. One of the brothers was Prince Boris.

When Svyatopolk, who later received the nickname the Accursed, became the Prince of Kyiv, Vladimir’s squad, as stated in the Tale of Bygone Years, advised Boris to take the Kiev throne from him. Boris refused to fight against his older brother, because Svyatopolk became the head of the family and took the place of his father. Obedience to elders was one of the most important virtues of a person, and Boris did not violate this tradition in order to gain power, although the Kiev throne at that time was, so to speak, the most desirable goal for all princes. The fact that one of the ancestors in the family sat on the Kiev throne for at least a few days immediately elevated the entire family in comparison with those who did not have such a privilege.

Svyatopolk's behavior was exactly the opposite. He planned, like Cain, to kill Boris, for which he decided to lull his vigilance. “I want to have love with you and I will give you additional possessions received from my father,” with these words he sends a messenger to his younger brother. Meanwhile, he ordered his servants to kill Boris.

When the messengers came to the Alta River to commit the atrocity, they heard Boris singing Matins. Why? Did no one inform the prince that an assassination attempt was being prepared on him? After all, there were scouts in Ancient Rus'. And if the prince knew about the assassination attempt, why didn’t he defend himself?

As we can see, Boris remained true to the principle that one should not contradict one’s elders. In addition, he did not want to do evil in response to evil, to kill in response to murder. He didn't want to take revenge. Perhaps he was disgusted by the fact that if open clashes with Svyatopolk had begun, he would have turned out to be an unwitting culprit of mass bloodshed, because many people on both sides would have died. Boris decided to humbly accept death at the hands of his brother. Among other things, he was motivated by concern for his soul. How would he appear before the Creator if he were killed on the battlefield? Having just committed murder?

Having sung psalms and canons, Boris began to pray:

- Lord Jesus Christ! Just as You appeared on earth in this image for the sake of our salvation, by Your own will allowing Your hands to be nailed to the cross, and accepting suffering for our sins, so grant me the ability to accept suffering. I do not accept this suffering from my enemies, but from my own brother, and do not blame him, Lord, for this to be a sin.

- As we see, martyrdom at the hands of murderers is desirable for the prince, because then he will be able to follow the example of Christ. For him this is not a punishment, but a reward. A reward that was also awaited by the first Christian martyrs who died in the arena of the Colosseum.

Boris cares not only about his own soul, but also about the soul of his brother. Since death is desired, he is glad that he will accept it from a relative, and not from a stranger, and asks God to forgive the foolish Svyatopolk. After all, he “doesn’t know what he’s doing”...

Svyatopolk's servants attacked Boris and pierced him with spears. Then they wrapped the body and took it to show Svyatopolk. It is surprising, but Boris did not die until his elder brother ordered his two Varangian servants to finish him off by piercing his heart with a sword.

It was Gleb's turn. News spread slowly throughout Ancient Rus', the messenger could easily have been killed, so Gleb probably did not know that his father Vladimir had died. Svyatopolk took advantage of this and informed his brother that his father was calling him to him because he was very ill. Gleb, like Boris, was obedient to his elders, and therefore hastened to come to his father.

Gleb was on the road when news came to him from another brother, Yaroslav, that Vladimir had died and Svyatopolk had killed Boris. Having learned about this, Gleb “cried out with tears,” as the chronicle says:

- Woe to me, Lord! It would be better for me to die with my brother than to live in this world. If I had seen, my brother, your angelic face, I would have died with you: now why am I left alone?.. If your prayers reach God, then pray for me, so that I too may accept the same martyr’s death.

“Just at this time, messengers from Svyatopolk arrived, and Gleb, like his brother, was killed with a sword.

“So he was sacrificed to God, instead of fragrant incense, a reasonable sacrifice, and accepted the crown of the kingdom of God, entering the heavenly abodes, and saw his longed-for brother there, and rejoiced with him with the indescribable joy that they were awarded for their brotherly love,” it says in The Tale of Bygone Years.

Two brothers (their Christian names are Roman and David) were canonized as passion-bearers. According to Metropolitan Juvenaly, “in the liturgical and hagiographic literature of the Russian Orthodox Church, the word “passion-bearer” began to be used in relation to those Russian saints who, imitating Christ, patiently endured physical, moral suffering and death at the hands of political opponents.”

Let us note that the canonization of Boris and Gleb served as an example for the canonization of Emperor Nicholas II and the royal family.

Perhaps the story of the official recognition of the first Russian saints is perhaps more interesting and richer in events than their biography. By the way, politics also plays an important role here.

After the murder of his cousins Boris and Gleb, Svyatopolk had to fight their brother Yaroslav the Wise. The strife ended with Svyatopolk fleeing to Poland, and Yaroslav taking the Kiev throne.

In 1054 Yaroslav died, and his sons divided the lands among themselves. Izyaslav (the eldest) remained in Kyiv, Svyatoslav (the middle) occupied the Principality of Chernigov (which, by the way, included the Murom lands of Gleb), and Vsevolod (the younger) became a prince in Pereyaslavl. The Principality of Rostov, where Boris had previously ruled, went to him.

Looking ahead, we note that the son of Vsevolod Yaroslavich was Vladimir Monomakh.

In ancient Russian literature there are several monuments dedicated to Boris and Gleb. A surprisingly clear political orientation can be traced in these documents.

Initially, the veneration of Boris and Gleb was not joint; the veneration of Gleb (although he was the younger) developed earlier in the Smolensk region, where the prince was killed, and in the capital of the principality, Chernigov. Reliquary crosses with the image of Gleb were made there, and his body was placed in a stone sarcophagus; at the same time, the relics of Boris rested in a wooden, less durable shrine (you can read about this in the article “The Tale of Bygone Years” for 1072, which tells about the transfer of the relics of the brothers to the church built for them in Vyshgorod).

The sons of Yaroslav were at enmity, and in 1073 Svyatoslav, having secured the support of Vsevolod, expelled his elder brother Izyaslav from Kyiv. This was a violation of the principle of succession to the throne laid down by their father, according to which the eldest man in the family should sit in Kyiv.

A year before, Izyaslav built a wooden church dedicated to Boris and Gleb. Svyatoslav decided to install a stone one instead. It was supposed to be a grandiose five-domed temple. The walls were raised 3 meters when the prince died. It was in 1076, and Izyaslav, who had been expelled 3 years ago, returned to Kyiv. After 2 years, he died in a battle with the son of Svyatoslav, and Vsevolod became the Prince of Kyiv. He resumed construction of the stone church of Boris and Gleb.

One can find interesting political aspects in the monuments dedicated to these saints. Researcher A. Uzhankov, for example, suggests comparing several texts. For example, articles from “The Tale of Bygone Years” and “The Tale of Boris and Gleb”, dedicated to the transfer of the relics of saints to the wooden church built by Izyaslav in Vyshgorod.

The Tale of Bygone Years only mentions Metropolitan George, who was officially installed in Rus' with the knowledge of Constantinople. In addition to George, the “Tale ...” speaks of Metropolitan Neophyte of Chernigov. In addition, in “The Legend...” there is an episode when Metropolitan George blesses Izyaslav, Svyatoslav and Vsevolod with the hand of Gleb, and the saint’s nail remains on Svyatoslav’s head as a sign of special grace. The Tale of Bygone Years does not talk about this.

What's the matter? There is an opinion that “The Legend…” was written by an author who was a political supporter of Svyatoslav, who ruled in Chernigov. Since the veneration of Gleb was widespread precisely in the Chernigov lands, the saint began to be considered the patron saint of the Svyatoslavichs. Therefore, princes, as an unknown storyteller writes, are blessed by the hand of the younger Gleb, and not the elder Boris, because Gleb is closer to the prince. That is why it is noted that the saint especially favors him.

It must be said that such support from the saint was very necessary for the prince, who decided to break the law and take the Kiev throne from his elder brother.

Taking history into account, the mystery of the second metropolitan, not mentioned in the chronicle, is also resolved. There is an opinion that at that time there were two metropolises in Rus' - Kiev and Chernigov. Hence the two metropolitans. There is another version. Svyatoslav ruled in Kiev from 1073 to 1076. After the celebrations of 1072 associated with the transfer of the relics of the saints, Metropolitan George left for Constantinople, and his successor John arrived only in 1077. Therefore, the metropolitan see was empty, and under the prince he could well to be the “acting” Metropolitan Neophytos, who was appointed by Svyatoslav. Hence the discrepancies between the “Tale,” compiled by an author who wanted to strengthen the authority of Yaroslav, and the “Tale of Bygone Years,” the compiler of which had a negative attitude towards the prince.

The “Tale…” itself was probably commissioned on the occasion of the construction of a new stone church of Boris and Gleb and should have been timed to coincide with the day of the second transfer of their relics, but Svyatoslav died before the construction was completed.

Despite the fact that Gleb was more popular in Rus' and began to be revered earlier, nevertheless, in the end, the veneration of Boris and Gleb, and not Gleb and Boris, was established. Why? Here again there is a political background. On the one hand, the head of the family should be the eldest in the family (as Yaroslav the Wise also bequeathed), and the eldest of the two brothers should be Boris. On the other hand, Gleb’s championship could not help but evoke associations with Svyatoslav, who revered him. But the prince broke his father’s covenant. It would have been much more correct in every sense to give a kind of “primacy” to Boris.

Moreover, in 1113, Vladimir Monomakh, so beloved in Rus', became the Prince of Kyiv. He improved the existing laws in every possible way, increased the international authority of the state (by the way, he was married to an English princess and was the grandson of the Emperor of Constantinople), and left his children a guide to a righteous life - the famous “Teaching...”. In a word, Monomakh was a very correct and pious prince, an example for all other rulers.

And Monomakh, as we remember, was the son of Vsevolod, and Vsevolod reigned in Pereyaslavl and owned the former lands of Boris, so Boris was considered the patron of the Vsevolodovichs. It is no coincidence that Monomakh recalls him in his “Teachings...”. So, from this point of view, primacy was given to Boris, the “patron” of the Kyiv Prince Vladimir, respected by the Russians.

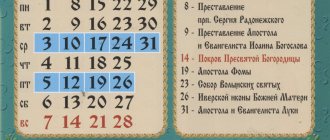

Under Monomakh 2 (in the new style - May 15), 1115, the 2nd transfer of the relics of Saints Boris and Gleb took place, which were placed in a wooden church that was finally rebuilt in Vyshgorod.

As for the time of the canonization of Boris and Gleb, then, in all likelihood, this happened between 1086 and 1093.

https://www.taday.ru/text/60839.html

TEMPLE OF THE HOLY DUCHESS OLGA IN OSTANKINO

Yesterday we celebrated the memory of the Holy Equal-to-the-Apostles Grand Duchess Olga. And today we glorify two saints who suffered a short time after her blessed death: the holy martyrs Theodore Varangian and his son John.

Saints Theodore and John lived in Kyiv during the reign of Saint Prince Vladimir, when the Varangians, the ancestors of today's Swedes and Norwegians, took a particularly active part in the state and military life of Rus'. Merchants and warriors, they paved new trade routes to Byzantium and the East, participated in campaigns against Constantinople, and made up a significant part of the population of ancient Kyiv and the princely mercenary squads. The main trade route of Rus' - from the Baltic Sea to the Black Sea - was then called “the path from the Varangians to the Greeks”.

The Monk Nestor the Chronicler reports that among the people of Kiev there lived a Varangian named Theodore, who had previously spent a long time in military service in Byzantium and received holy Baptism there. Theodore had a son, John, a handsome and pious young man who, like his father, professed Christianity.

At that time (and this happened even before the Baptism of Rus') human sacrifices were common. Theodore's son John was chosen as a sacrifice to idols. When those sent to Theodore reported that his son “the gods chose for themselves, let us sacrifice him to them,” the old warrior resolutely replied: “This is not the gods, but a tree. Today it exists, but tomorrow it will rot. They do not eat, drink or speak, but are made of wood by human hands. God is One, the Greeks serve and worship Him. He created the heavens and the earth, the stars and the moon, the sun and man, and destined him to live on earth. What did these gods do? They themselves are created. I will not give my son to the demons.”

This was a direct Christian challenge to the customs and beliefs of the pagans. An armed crowd of pagans rushed to Theodore, destroyed his yard, and surrounded his house. Theodore, according to the chronicler, “stood in the entryway with his son,” courageously, with weapons in his hands, met his enemies. (Seniami in ancient Russian houses was the name for a covered gallery on the second floor, built on pillars, to which a staircase led). He calmly looked at the raging pagans and said: “If they are gods, let them send one of the gods and take my son.” Seeing that in a fair fight they could not defeat Theodore and John, brave, skilled warriors, the besiegers cut down the pillars of the gallery, and when they collapsed, they crowded on the confessors and killed them.

Already in the era of St. Nestor, less than a hundred years after the confessional feat of the Kyiv Varangians, the Russian Orthodox Church revered them in the host of saints. Theodore and John became the first martyrs for the holy Orthodox faith in the Russian land, and the copyist of the Kiev-Pechersk Patericon, Bishop Simon, Saint of Suzdal calls them the first “Russian citizens of the heavenly city.”

Troparion to the martyrs Theodore Varangian and his son John of Pechersk

Passion-bearers of the Lord, Theodore and the youth John, glory! Blessed is the Russian land, drunk with your blood, and our fatherland rejoices, in which you are the first, having put to shame idols, you will boldly confess Christ and suffer for Him. That which is Good, pray, until the end of the century in our country, the Orthodox Church will be unshakably established and all Russian people will be preserved in true faith and piety.