Our Lady of Oranta Wall Unbreakable. Mosaic of St. Sophia Cathedral in Kyiv. 1040s

Our Lady of Oranta Wall Unbreakable. Mosaic of St. Sophia Cathedral in Kyiv. 1040s Limestone soil, smalt, brick, colored stone. Place of creation Kyiv, Ukraine. Era, style, direction Kievan Rus

Bibliography: Lazarev V.N. Frescoes of Sophia of Kyiv. – M., 1960; Lazarev V.N. History of Byzantine painting. – M., 1986; Lazarev V.N. Old Russian mosaics and frescoes of the 11th–15th centuries. – M.: Art, 1973; Likhacheva V. Art of Byzantium IV-XV centuries. – L., 1986; Logvin G.N. Sofia Kievskaya. – Kiev, 1971; Kondakov N.P. Iconography of the Mother of God. T.2. – St. Petersburg 1915; Bukharev I., archpriest. Miracle-working icons of the Blessed Virgin Mary. (Their history and images). – M., 1901.

The image of the Mother of God with her hands raised in prayer and without the Child is called “Oranta” (from the Latin orans - praying). According to ancient tradition, such full-length images were often placed at the top of the altar, in the conch. If in the early stages of the formation of church institutions Jesus was depicted symbolically, then the image of the Mother of God was always more realistic and correlated with the gospel story of the life of the Virgin Mary. Features of the external appearance of the Blessed Virgin in verbal descriptions were preserved only by authors of later times. The church historian Nicephorus Xanthopulus (Callistus) at the beginning of the 14th century most fully and scrupulously put them together: “She was of average height or, as others say, slightly above average; Her complexion was like the color of a grain of wheat; Her hair was light brown and somewhat golden; the eyes are clear, the gaze is penetrating, with pupils the color of olives; the eyebrows are slightly inclined and moderately black: the nose is oblong; blooming lips filled with sweet speeches; the face is not round and not sharp, but somewhat oblong: the arms and fingers are long.” The “Oranta” of the Kyiv Cathedral fully corresponds to these ideas about the historical appearance of the Mother of God. “Our Lady of the Indestructible Wall” occupies an exceptional place in the system of mosaics of St. Sophia of Kyiv. “Oranta”, 5.45 meters high, stops the gaze of everyone entering the cathedral and is perceived as the main, dominant image in the entire temple. The invoking Mother of God raised her hands in prayer to the Savior Almighty, whose image is located in the mirror of the central dome. Towering over the main altar of the St. Sophia Cathedral, “Oranta” remained intact for almost ten centuries, despite the fact that both the city and the cathedral itself were repeatedly destroyed. The Russian people believed that the Ever-Virgin was a miraculous protector of Rus', the capital of Kyiv, and all Orthodox people. According to legend, our Fatherland will not perish as long as the Mother of God Oranta “The Unbreakable Wall” stretches out her hands over it. On a scarlet belt hangs a lention (towel), with which, according to popular belief, the Compassionate One of God wipes away the countless tears of the common people. The Mother of God stands on a pulpit, an imperial platform, decorated with precious stones; in addition, she is wearing red boots, for She is represented as the Queen of Heaven. The head of the Gracious Mother is covered with a scarf (omophorion) thrown over the left shoulder. Later, this cloth will receive an original interpretation in Rus' as the “Protection of the Mother of God,” with which She spiritually hid the Russian Land from evil misfortunes, troubles and enemies. The shades of Her blue robe with dark folds stand out clearly against the general golden background of smalt. Individual pieces of the mosaic are placed at different angles in such a way that a dim glow is always visible around the figure of the Virgin Mary. The color palette of the mosaic is very rich: blue smalt has twenty-one shades, and green – thirty-five. A remarkable feature of the Kyiv “Oranta” is its proportions. The mosaicist faced great difficulties in constructing an image on the concave surface of the apse. In order to prevent distortions in the perception of the figure of the Virgin Mary, the master had to find special proportional relationships. V.N. Lazarev notes in this regard: “We cannot close our eyes to the fact that, in terms of its proportions, the figure of “Oranta” is poorly suited for the place allotted to it. She is too short and squat. The head (0.90 m) is only one sixth of the figure. The lower part of the latter (2.80 m) is disproportionately short in relation to the size of the head (1:3). If the master had taken into account the perspective reduction, then he should have lengthened the lower part of the figure, which he did not do. That’s why the figure seems so short and big-headed, which gives it a somewhat archaic character” (Lazarev V.N. Mosaics of Sophia of Kyiv. - M., 1960. P. 100.). The traditional gesture of Oranta goes back to the Old Testament history of Ancient Israel: raised hands - the original prayer pose of the Jews. According to the Book of Exodus, during the long and grueling battle between the Israelites and the Amalekites at Mount Horeb, Moses raised his hands in prayer to Yahweh God for his people. “And when Moses lifted up his hands, Israel prevailed; and when he lowered his hands, Amalek prevailed” (Exodus 17:11). Moses' prayerful participation in the battle predetermined the victory of the Jews. An episode from the Old Testament was reinterpreted in the Middle Ages as a spiritual warfare for the right faith and the Christian people, as a tension of theurgic power, from which the enemies of the city and the people should be squandered. For an entire eternity, Oranta, who has not lowered her raised hands, is truly the “Voevoda” for the Kyiv Christian people, selflessly taking on the military work of intercession for them, just as Moses took on the burden of his people. The Oranta canon is obviously the earliest in the history of the formation of the iconography of the Mother of God. In the Roman catacombs of the 2nd-4th centuries, there are several dozen images of women with raised arms. Some of them, most likely, are conventional portraits of Christian women buried here, while others - with the inscription “Maria” or “Mara” - can be attributed to the Virgin Mary. The catacomb frescoes of the Blessed Virgin are still very far from the canonically stable image of Oranta, but they already carry in themselves in symbolic form some theological ideas. Starting from the second half of the 9th century, after the establishment of icon veneration in Byzantium, when the formation of the temple painting system was completed, the image of “Our Lady Oranta” was usually placed in the upper part of the altar. In Eastern Christianity, the image of “Oranta” was given a city-protective function, the origins of which lie in church hymns, where the Mother of God is likened to the “kingdom of the indestructible wall,” the wall “invincible,” “indestructible,” “immovable.” So, for example, in the “Akathist to the Mother of God” in 12 ikos it is sung: “Rejoice at the kingdom, indestructible wall.” In Byzantium, the Mother of God was revered as the intercessor and patroness of the city and its fortress walls. The famous Constantinople “Oranta” in the Blachernae monastery is known, which was considered the protector of all Byzantium. With the adoption of Christianity, these ideas were borrowed by Kievan Rus. In the theological program of temple painting, the idea of the intercession of “Oranta” acquired an expanded meaning. The prayer of the Most Pure Virgin connected the Kingdom of God, represented at the top of the temple, with the earthly, “low world,” where the parishioners stood during the service. Through the Mother of God, the grace of the Lord God and the sanctification of human flesh thus descends. This is where the personification of “Our Lady Oranta” with the Christian temple and in general with the entire New Testament Church originates. This is reflected, in particular, in the composition of “Ascension”. The mosaic master who created the Sofia "Oranta" also created the "Pantocrator" and, apparently, the "Archangel" in the main dome of the cathedral. This is evidenced by the common mosaic texture, shortened and enlarged proportions of the figures, and a similar interpretation of rectilinear folds.

To the beginning of the section “Iconography”>>>

Orthodox Life

The complex of mosaics of St. Sophia of Kiev is a unique work of its kind, since it is the only mosaic ensemble of Kievan Rus that has survived to such a significant extent to our time (the mosaics of the cathedral church of the St. Michael's Golden-Domed Monastery in Kiev have partially survived - the temple itself was destroyed in the 30s of the XX centuries, the mosaics of the Tithe Church have not survived at all - only individual pieces of smalt have reached us).

St. Sophia Cathedral in Kyiv

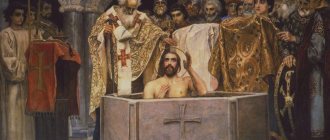

Built in the first half of the 11th century, the Cathedral of St. Sophia was conceived as the place of the metropolitan see (by the way, it is appropriate to remember that the chronicle nickname of Kiev - “mother of Russian cities” - is a literal copy from the Greek language: “mother of cities” - metropolis) and, accordingly, as the largest and most luxurious temple of Rus'.

Saint Sophia Cathedral. Interior

The huge five-nave, thirteen-domed cathedral was created by Byzantine masters, but, interestingly, we do not find direct analogues of Sophia of Kyiv in the Byzantine architecture of that period.

The interior decoration is also distinguished, primarily by a mixture of techniques - mosaics and fresco painting (in Byzantium, as a rule, churches were painted either with paints or with mosaics). But Rus' in the 11th century was the cultural periphery of the Byzantine world, and mosaics were very expensive (not counting the costs of transporting the materials themselves). Therefore, a compromise decision was made: the key parts of the temple (altar, dome, pre-altar pillars and dome arches) were decorated with mosaics, and the rest of the temple space was painted.

The mosaics of Sophia of Kyiv belong to the late Macedonian style. The Macedonian style (Macedonian Renaissance) is the general name for Byzantine art during the reign of the Macedonian imperial dynasty (867–1056). This was a period of global revival of church art after the iconoclastic persecution. At the beginning of the Macedonian period, classical ancient forms of painting were strong, but by the 11th century the trends had changed. During this period there is a turning point towards greater severity and asceticism. The forms freeze, the figures of the saints acquire severity, immobility, and symmetry. It is assumed that such transformations of the Macedonian style are associated with the influence of monastic internal “interior” aesthetics, which at the beginning of the 11th century became, if not dominant, then very influential. And it was precisely during this period that the activity of such a great representative of the aesthetics of asceticism as St. Simeon the New Theologian (+1022). This strict, ascetic-oriented, intensely spiritual style is fully manifested in the mosaics of Kyiv Sofia.

When we enter the St. Sophia Cathedral, the first thing that opens to our eyes is the majestic image of the Virgin Mary, 5.45 meters high, in the altar apse. The concave surface of the apse itself reflects light in such a way that it creates the illusion of a golden background shining around the figure of the Mother of God. This is further emphasized by smalt cubes, which are inserted into the background plaster at different angles.

Fragmented smalt mosaics of St. Sophia of Kyiv

The color palette of Kiev-Sofia mosaics is quite rich, for example, the blue color has 21 shades, green – 34, etc. Even the gold backgrounds are heterogeneous, the gold color has 25 shades. In total, the mosaics of St. Sophia Cathedral have 177 shades of different colors.

The Mother of God is depicted praying with her hands raised up; this ancient gesture of prayer is depicted in the paintings of the early Christian catacombs. Based on this gesture, the Mother of God image of St. Sophia Cathedral is often called Oranta, that is, praying. This image is also called the “Unbreakable Wall”. This phrase, originally borrowed from the 12th ikos of the akathist to the Most Holy Theotokos “Rejoice, indestructible wall of the kingdom,” over time acquired a literal interpretation among the people. Indeed, over all the centuries of the cathedral’s existence, despite many devastations, the wall with this image was never destroyed. That’s why the belief arose that Orthodox Kyiv would stand as long as the Lady of God praying was in the St. Sophia Cathedral with her hands raised...

Along the perimeter of the apse arc there is a Greek inscription, which once again emphasizes the intercession of the Mother of God: “ὁ Θεὸς ἐν μέσῳ αὐτῆς καὶ οὐ σαλευθήσεται·βοηθήσει αὐ “God is in the midst of her and does not move: God will help her in the morning” (Ps. 45:6).

The wide-open eyes of the Mother of God, her calm, detached gaze, large facial features - all these are signs of a new ascetic style. Her hands are raised up - to where the Almighty Christ is depicted in the dome.

The image of Christ Pantocrator - the Pantocrator is executed in the same strict manner, in the same laconic language characteristic of the late Macedonian style.

A round shield with a diameter of 4.1 m with the image of the Savior in the dome is surrounded by four archangels in rich Byzantine ceremonial robes. Just as earthly courtiers surround the earthly emperor, angels surround the Heavenly King. Each of them holds symbols of supreme power: an orb and a long staff - labarum, which is crowned with a panel with the Greek inscription: “άγιος, άγιος, άγιος - Holy, Holy, Holy.” This reminds us of the Holy Scripture, which speaks of the seraphim surrounding the heavenly Throne: “And they called to each other and said: Holy, Holy, Holy is the Lord of Hosts! the whole earth is full of His glory!” (Isa. 6:3), and these same words are part of the liturgical Cherubic song.

The caesuras between the figures of angels, filled with a golden background, form a golden cross in the dome (it must be said that the theme of the combination of a cross and a circle is repeated several times in the interior decoration of St. Sophia of Kyiv).

Unlike the “unbreakable” apse wall, the dome of St. Sophia of Kyiv was seriously damaged. Of the four archangels, only one has survived - in a blue robe. The remaining three were painted in 1884 in oil paints by the outstanding artist M.A. Vrubel, who, using strokes, tried to imitate a mosaic surface and quite accurately reproduced the style of the images.

Just like the dome, the drum, where the images of the twelve apostles were located in the walls of the twelve windows, was significantly damaged. Only one image has survived (and only partially, waist-deep) - that of the Apostle Paul.

Under the dome, in the sails, there were images of the four evangelists. Surprisingly, as in the case of the apostles and archangels, only one of these images has survived to this day - the Apostle Mark. It can be noted here that photographs taken from the dome itself convey many images in a “distorted” form, because these images were originally designed for the viewer located below, for which Byzantine masters used special perspective distortions.

The figure of John the Evangelist has been partially preserved (legs and arms).

A very small fragment (a desk) remains from the image of the Apostle Matthew...

If you draw a mental line from the praying Mother of God to the Pantocrator in the dome, you can see that Christ is depicted three times on this axis: the Pantocrator in the dome itself, Christ the priest at the level of the evangelists and below - in the arch, directly above Oranta in the Deisis scene.

Christ the Priest presents us with a rather rare iconographic type, of which very few examples have survived. Here the Savior is depicted in His traditional, and not in priestly attire. And His priesthood is indicated only by the hairstyle adopted by the clergy of that period - a cropped crown, the so-called. humenzo (in the Russian Church this type of hairstyle was preserved until the middle of the 17th century, and in the Roman Catholic Church it took place literally until recently (“tonsure”) until abolition by Pope Paul VI in 1973).

Deisis (in Greek - prayer). Once again it reminds us of the intercession of the Mother of God and the saints before the Savior for Christians.

In the center of the composition is Christ in a traditional image. And on either side of him is the “most honorable of the cherubim” and “the most glorious of the seraphim” the Mother of God and “the greatest of those born of women” John the Baptist - the main prayer books for the Christian race.

In the Altar, below the Mother of God Oranta, in two-level registers there are images of the Communion of the Apostles and below - the hierarchical rite.

In the Communion scene, the Altar is depicted in the center with liturgical paraphernalia on it and a canopy above it. Around the Throne stand angels in the form of deacons in surplices with ripids.

On the sides of the Throne we see the Savior depicted twice, who from His hands gives communion to the apostles (six on each side), on the one hand - the Body, on the other - the Blood.

The location of this composition precisely in the center of the Altar is not typical of the Byzantine tradition itself. There is an opinion that in this way in Rus', which adopted Christianity from Byzantium, it was the Eastern tradition of communion of two types that was emphasized, in contrast to the tradition that had taken place by that time in the West, even before the fall of Rome, of giving communion to the laity only of the Body.

Below the Apostolic Eucharist is the “hierarchal rite” - an image of a group of saints - holy bishops, among whom we see miracle workers, martyrs and teachers of the Church. But among the holy bishops there are also two holy deacons: Stephen and Lawrence.

The lower part of these images was also significantly damaged and was later painted over.

Holy rite. John Chrysostom

Gregory the Wonderworker

Clement, Pope

Archdeacon Lavrenty

General view of the main dome of Hagia Sophia with supporting arches

The four arches supporting the dome are decorated with medallions with images of the forty martyrs of Sebaste (15 such medallions have survived to this day: 10 on the southern arch and 5 on the northern). The martyr images located in the arches supporting the vault were probably meant to remind that the Church was built on the blood of martyrs.

Each of the martyrs holds a cross in one hand, as a symbol of his suffering, and in the other, a crown, as a symbol of heavenly reward.

Combined image of the Annunciation scene on the pre-altar pillars

On the pillars located around the altar apse, there is an image of the Annunciation of the Blessed Virgin Mary - the beginning of New Testament history. On one pillar is the Archangel Gabriel, whose image is accompanied by a greeting written in Greek: “Rejoice, full of grace...”, on the other is the Mother of God herself. Nearby is a Greek inscription: “Behold the handmaid of the Lord...”

From other mosaics reminiscent of the Old Testament, only the image of the high priest Aaron, located on the inner pre-altar arch, has survived.

Mosaic ornaments of Sophia of Kyiv. Decoration of the back of the throne of the Kyiv Metropolitans

Many ornaments have also been preserved, which, where necessary, shade or emphasize the main images.

The mosaics of Sophia of Kyiv embodied the results of the development of the Macedonian style of Byzantine art. Their strict, restrained, inward-directed beauty raised the thoughts of ancient Russian Christians to Divine truths, the image of which Christian icons are called to be. This beauty, even now, almost nine centuries later, continues to reveal these truths to our contemporaries.

Dmitry Marchenko

Literature: Lazarev V. N. Old Russian mosaics and frescoes of the 11th–15th centuries. M.: Art, 1973. National Nature Reserve “Sofia Kievska”. K.: Baltiya-Druk, 2011. Bychkov V.V. Small history of Byzantine aesthetics. K.: Path to Truth, 1991. Kolpakova G. S. The Art of Byzantium. Early and middle periods. St. Petersburg: ABC-classics, 2010. History of icon painting of the 6th–20th centuries. M.: Art-BMB, 2002. Sarabyanov V.D., Smirnova E.S. History of Old Russian painting. M.: PSTGU, 2007.

See also: Graffiti of Sofia of Kyiv. Memory of Ancient Rus'