ICON PAINTING

ICON PAINTING, the field of painting, the process of creating icons - prayer images. Greek the word εἰϰών (image, image) served as a general name for sacred images in the Eastern Orthodox world, therefore, to I. in its traditions. understanding, in addition to the icons themselves, also included frescoes, mosaics (their creation was called icon painting), book miniatures, sacred images on art objects of small forms (on crosses, chalices, panagias, etc.).

"Apostle Peter." Encaustic. 6th century Monastery of St. Catherine on the Sinai Peninsula.

"The Virgin and Child." Encaustic. 2nd half 6th century Museum of Art named after B. and V. Khanenko (Kyiv).

"Annunciation". Beginning 14th century From the Church of St. Clement in Ohrid (Macedonia).

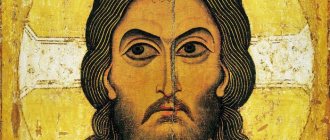

The earliest information about images of Christ and the apostles Peter and Paul painted on boards is contained in the “Ecclesiastical History” (VII, 18) of Eusebius of Caesarea. A story about painting the image of Christ is included in the sir. apocryphal "Teachings of Addai" beginning. 5th century Perhaps as early as the 6th century. There was a legend about the creation of the image of the Mother of God by the Evangelist Luke. The first surviving icons date back to the 6th century. (“Christ the Pantocrator” and “The Virgin and Child, Angels and Holy Martyrs”, both from the Monastery of St. Catherine on the Sinai Peninsula). The 7th Ecumenical Council (787) defined the subject of iconography (“sacred images”) and emphasized that icon painting “was not invented by painters at all, but on the contrary, it is an approved statute and tradition of the Catholic Church... Only the technical side of the matter belongs to the painter...” ( Acts of the Ecumenical Councils. 2nd ed. Kazan, 1891. T. 7. pp. 226–227). The Council noted that contemplation of “icon painting” is a recollection of the godly life of holy people. “What the word communicates through hearing, painting shows silently through the image” (Ibid. p. 249). I. was initially considered a pious activity, but in Greek. Church status, moral and prof. the qualities of icon painters were not officially regulated. In Rus', such regulation was carried out by the Council of the Stoglavy (1551), which determined that the painter must lead a virtuous life, learn from good masters and have a talent given from God. Moral and ethical the requirements for artists practically coincided with the requirements for clergy; Bishops were accordingly instructed to protect icon painters “more than ordinary people.”

"St. Nicholas the Wonderworker." 14th–15th centuries Monastery of the Transfiguration (Meteora, Greece).

"Fyodor Stratelates" Mosaic icon. Beginning 14th century Byzantium. Hermitage (St. Petersburg).

"Saints Dmitry and George." 16th century Monastery of Varlaam (Meteora, Greece).

Technique and artist I.'s methods in the first period of its existence were common with Hellenistic. painting and gravitated towards illusionism (writing with wax paints on a board or canvas, conveying the volume and texture of what is depicted). Beginning in the 9th century, in the post-iconoclastic period, in India, in parallel with changes in writing techniques and techniques, qualities that had previously appeared sporadically and were characteristic of the Middle Ages crystallized. will depict lawsuit in general. Icon painters began to use preim. tempera paints – miner. pigments ground on egg yolk or gum; Mosaic and ceramic techniques are less common. As a basis in tempera painting, boards with a recess-like ark in the center were used. parts. The boards were pre-primed with gesso - a mixture of chalk or alabaster with fish glue; fabric (pavolok) was glued under the gesso for better adhesion to the board. A brush pattern was applied to the smooth gesso, and sometimes the contours of halos and figures were scratched with graphite (in post-Byzantine painting and other elements of the composition). Writing methods have become simpler, and the sankir method has become widespread, when faces and open parts of the body are painted on a dark lining - sankir. Sankir (usually a mixture of ocher and soot) was left open in shaded areas (along the contour of the face, in the eye sockets, in the nasolabial and chin cavities), the rest was lightened by covering with several layers of ocher (swirling) with a gradually increasing addition of white. In some places, red paint or its mixture with ocher (rudder) was applied. The brightest places were emphasized with strokes of pure white - vivification. Ocher could be applied separately. strokes or liquid paint, where the strokes merged (melting). Swirling with brush strokes, often large, is characteristic of Byzantium. and pre-Mongol Russian I., melting became widespread in Rus' from the end. 14 – beginning 15th centuries Clothes were painted in local colors, adding volume with the help of spaces (white glazes) and fills (tonal shading). Sometimes the bleaching spaces were replaced with colored ones, contrasting in color tone, or with leaf gilding - ink. From the 17th century rus. Icon painters used created gold for spaces, that is, paint made from ground sheet gold, which made it possible to change the density of the stroke.

"The Miracle of George about the Serpent." 15th century Tretyakov Gallery (Moscow).

"Saint George with his life." 1838. Icon painter Dimitar Kanchov from Tryavna. Historical Museum (Veliko Tarnovo, Bulgaria).

In icon-painting workshops, obviously, from ancient times there was a division of labor. Excavations of the estate of a 12th century Novgorod icon painter. it was revealed that the boards for the icons were made by a woodworking master; It is likely that the paints were not prepared by the painter himself. Most likely, in ancient times apprentices were used for auxiliary work. The division of masters into “lichniks” and “dolichniki” (“payers”) has been known since the 17th century; it, apparently, was not determined by the artist himself. factors, but large volumes of orders. However, such a division did not mean a narrowing of the specialization of the icon painter, who could paint the entire icon (for example, Palekh masters of the 19th century).

The basis of creativity method in India - copying samples, although it was officially established in Rus' only by the Stoglavy Cathedral. Since all icons were considered to go back to sacred and unchanging prototypes, the icon painter was focused not on innovation, but on reproducing the prototype through an ancient and “good” model. This contributed to I.’s impersonality and leveling of the author’s principle. However, as a rule, only iconographic images were reproduced. scheme; coloristic the decision was repeated in the most general terms, the details usually varied. The artist strove for recognition of the plot or the miraculous original, but did not set himself the goal of creating an absolutely identical copy. This approach provided a sufficient degree of freedom for the icon painter and the possibility of development and enrichment. At the same time, the created image had to comply with the tenets of faith. The use of traces and facial scripts (illustrative aids for icon painters) has been known only since the 16th century, although there is an assumption of their existence back in the pre-iconoclast era. Drawings and originals served as auxiliary material for constructing compositions and when depicting little-known saints and subjects. In post-Byzantine art, Western Europeans were used as prototypes. engravings that made it possible to update the set of iconographic images. schemes and use new forms of conveying volume and space.

The tempera technique, the sankir way of writing faces and the orientation towards samples were steadily preserved in modern times in tradition. I., almost entirely Old Believers (among the Orthodox, icon painting evolved and was no longer traditional, even if traditional writing techniques were preserved), and in the widespread “golden-white” icons, considered “Greek writing.” The conservation of icon painting techniques among the Old Believers was programmatic; among icon painters who belonged to the official Churches, these methods continued to exist, because they made it possible to introduce Baroque features into I. without changing the existing teaching methods. In I. academic. directions (from the late 18th century) used materials, techniques and techniques of secular painting (oil painting on canvas on clean ground or thin colored underpainting; in the late 19th century zinc was sometimes used as a base). Iconographic circle samples expanded to include works by prominent Europeans. masters This branch of I. completely moved away from the Middle Ages. image transmission techniques. Modern I. basically retrospectively.

Brief History of Icon Painting

Iconography - (icon and write) - icon painting, theology in colors - a type of religious painting based on the Tradition of the Christian Church and the Holy Scriptures. Icon painting creates sacred images that are called upon to raise worshipers from image to prototype, hence the frequent name of the icon - image, in modern language, a projection of the spiritual world in the material.

Icon painting originated in apostolic times. In the first century after the Nativity of Christ, according to Church tradition, the first icon was painted by the Apostle Luke himself on a simple wooden tabletop. This image began to be called the image of the Vyshgorod, and then the Vladimir Icon of the Mother of God of Tenderness, so named after the transportation of the icon of St. Prince Andrei Bogolyubsky to Vladimir. From the first centuries of Christianity, even during persecution, Christians began to depict the foundations of their faith with symbols. Evidence of this is the paintings in the Roman catacombs that have survived to this day.

Icon painting survived the period of iconoclasm. For two centuries (from the 8th to the 9th), the persecution of holy images continued, which were declared idols, and the people who worshiped them idolaters. The result of iconoclasm was the barbaric destruction of icons, frescoes, mosaics, the destruction of painted altars in many Byzantine churches, and icon worshipers were persecuted and destroyed. The Council of Constantinople in 842 restored the veneration of icons and condemned iconoclasm. After the council, which condemned iconoclasm and restored icon veneration, a church celebration was held, which fell on the first Sunday of Great Lent. In memory of this event, on the first Sunday of Great Lent, the Church established a holiday for the restoration of icon veneration, called the “Triumph of Orthodoxy.” On February 15, the cycle of Christmas holidays ends. The Presentation of the Lord marks the meeting of Jesus with Simeon. By observing the weather on this day, you can predict the harvest and weather. Also on this day, the Slavs performed various rituals for health and peace in the family. Interestingly, swimming was prohibited.

Traditional icon painting in Rus' was borrowed (like the entire structure and Rules of Divine Services) from Byzantium. The first teachers of icon painting were invited from there. Icon painting began in the 10th century and was marked by the Baptism of Rus'. Icon painting was the leading church-based fine art in Rus' until the 8th century, when it was gradually replaced by secular types of fine art. Icon painting schools appeared in various principalities. Each school had its own individual writing style.

Icon

Main article: Icon

Icon

(cf. Greek εἰκόνα from other Greek εἰκών “image”, “image”) - in Christianity (mainly in Orthodoxy, Catholicism and ancient Eastern churches) an image of persons or events of sacred or church history, which is the subject of veneration, which among Orthodox and Catholics is enshrined in the dogma of the Seventh Ecumenical Council of 787.

In the narrow sense accepted in art history, icons are usually called images made within the framework of the Eastern Christian tradition on a hard surface (mainly on a linden board covered with gesso, that is, alabaster diluted with liquid glue) and equipped with special inscriptions and signs.

Notes

- ↑ 1 2 Yakovleva A.I., Krasilin M.M.

[www.pravenc.ru/text/389066.html Iconography] // Orthodox Encyclopedia. Volume XXII. - M.: Church-scientific, 2009. - P. 60-65. — 752 p. — 39,000 copies. — ISBN 978-5-89572-040-0 - ↑ 12

[interpretive.ru/dictionary/968/word/ikonopis Iconography] // Encyclopedia “Art” in 4 volumes / Ed. A. P. Gorkina, 2007 - Somov A.I.

Iconography // Encyclopedic Dictionary of Brockhaus and Efron: in 86 volumes (82 volumes and 4 additional). - St. Petersburg, 1890-1907. - [dic.academic.ru/dic.nsf/enc1p/19346 Iconography] // Modern Encyclopedia. 2000.

- Uspensky B. A. On the semiotics of the icon // Works on sign systems. Vol. V. Scientific notes of the University of Tartu. Vol. 28. Tartu, 1971. pp. 178−223

- Gorbunova-Lomax I. N. Icon: truth and fiction. St. Petersburg: Satis, 2009. 289 p.

Excerpt characterizing Iconography

Prince Andrei looked with contempt at these endless, interfering teams, carts, parks, artillery and again carts, carts and carts of all possible types, overtaking one another and jamming the dirt road in three or four rows. From all sides, behind and in front, as long as one could hear one could hear the sounds of wheels, the rumble of bodies, carts and carriages, the clatter of horses, blows of a whip, shouts of urging, curses of soldiers, orderlies and officers. Along the edges of the road one could constantly see either fallen, skinned and unkempt horses, or broken carts, in which lonely soldiers were sitting, waiting for something, or soldiers separated from their teams, who were heading in crowds to neighboring villages or dragging chickens, sheep, hay or hay from the villages. bags filled with something. On the descents and ascents the crowds became thicker, and there was a continuous groan of shouts. The soldiers, sinking knee-deep in mud, picked up guns and wagons in their hands; whips beat, hooves slid, lines burst and chests burst with screams. The officers in charge of the movement drove forward and backward between the convoys. Their voices were faintly audible amid the general roar, and it was clear from their faces that they despaired of being able to stop this disorder. “Voila le cher [“Here is the dear] Orthodox army,” thought Bolkonsky, remembering the words of Bilibin. Wanting to ask one of these people where the commander-in-chief was, he drove up to the convoy. Directly opposite him was riding a strange, one-horse carriage, apparently constructed at home by soldiers, representing a middle ground between a cart, a convertible and a carriage. The carriage was driven by a soldier and sat under a leather top behind an apron, a woman, all tied with scarves. Prince Andrei arrived and had already addressed the soldier with a question when his attention was drawn to the desperate cries of a woman sitting in a tent. The officer in charge of the convoy beat the soldier, who was sitting as a coachman in this carriage, because he wanted to go around others, and the whip hit the apron of the carriage. The woman screamed shrilly. Seeing Prince Andrei, she leaned out from under her apron and, waving her thin arms that had jumped out from under the carpet scarf, shouted: “Adjutant!” Mr. Adjutant!... For God's sake... protect... What will this happen?... I am the doctor's wife of the 7th Jaeger... they won't let me in; We fell behind, we lost our own... - I’ll break you in a cake, wrap it up! - the embittered officer shouted at the soldier, - turn back with your whore. - Mr. Adjutant, protect me. What is this? – the doctor shouted. - Please let this cart pass. Can't you see that this is a woman? - said Prince Andrei, driving up to the officer. The officer looked at him and, without answering, turned back to the soldier: “I’ll go around them... Back!...” “Let me through, I’m telling you,” Prince Andrei repeated again, pursing his lips. - And who are you? - the officer suddenly turned to him with drunken fury. - Who are you? You (he especially emphasized on you) are the boss, or what? I'm the boss here, not you. “You go back,” he repeated, “I’ll smash you into a piece of cake.” The officer apparently liked this expression. “You shaved the adjutant seriously,” a voice was heard from behind. Prince Andrei saw that the officer was in that drunken fit of causeless rage in which people do not remember what they say. He saw that his intercession for the doctor’s wife in the wagon was filled with what he feared most in the world, what is called ridicule [ridiculous], but his instinct said something else. Before the officer had time to finish his last words, Prince Andrei, with a face disfigured from rage, rode up to him and raised his whip: “Please let me in!” The officer waved his hand and hurriedly drove away. “It’s all from them, from the staff, it’s all a mess,” he grumbled. - Do as you please. Prince Andrei hastily, without raising his eyes, rode away from the doctor's wife, who called him a savior, and, recalling with disgust the smallest details of this humiliating scene, galloped further to the village where, as he was told, the commander-in-chief was located. Having entered the village, he got off his horse and went to the first house with the intention of resting at least for a minute, eating something and bringing into clarity all these offensive thoughts that tormented him. “This is a crowd of scoundrels, not an army,” he thought, approaching the window of the first house, when a familiar voice called him by name. He looked back. Nesvitsky’s handsome face poked out from a small window. Nesvitsky, chewing something with his juicy mouth and waving his arms, called him to him. - Bolkonsky, Bolkonsky! Don't you hear, or what? “Go quickly,” he shouted. Entering the house, Prince Andrei saw Nesvitsky and another adjutant eating something. They hastily turned to Bolkonsky asking if he knew anything new. On their faces, so familiar to him, Prince Andrei read an expression of anxiety and concern. This expression was especially noticeable on Nesvitsky’s always laughing face. -Where is the commander-in-chief? – asked Bolkonsky. “Here, in that house,” answered the adjutant. - Well, is it true that there is peace and surrender? – asked Nesvitsky. - I'm asking you. I don’t know anything except that I got to you by force. - What about us, brother? Horror! “I’m sorry, brother, they laughed at Mak, but it’s even worse for us,” Nesvitsky said. - Well, sit down and eat something. “Now, prince, you won’t find any carts or anything, and your Peter, God knows where,” said another adjutant. -Where is the main apartment? – We’ll spend the night in Tsnaim. “And I loaded everything I needed onto two horses,” said Nesvitsky, “and they made me excellent packs.” At least escape through the Bohemian mountains. It's bad, brother. Are you really unwell, why are you shuddering like that? - Nesvitsky asked, noticing how Prince Andrei twitched, as if from touching a Leyden jar. “Nothing,” answered Prince Andrei. At that moment he remembered his recent clash with the doctor’s wife and the Furshtat officer. -What is the commander-in-chief doing here? - he asked. “I don’t understand anything,” said Nesvitsky. “All I understand is that everything is disgusting, disgusting and disgusting,” said Prince Andrei and went to the house where the commander-in-chief stood. Passing by Kutuzov's carriage, the tortured horses of the retinue and the Cossacks speaking loudly among themselves, Prince Andrei entered the entryway. Kutuzov himself, as Prince Andrei was told, was in the hut with Prince Bagration and Weyrother. Weyrother was an Austrian general who replaced the murdered Schmit. In the entryway little Kozlovsky was squatting in front of the clerk. The clerk on an inverted tub, turning up the cuffs of his uniform, hastily wrote. Kozlovsky’s face was exhausted - he, apparently, had not slept at night either. He looked at Prince Andrei and did not even nod his head to him. – Second line... Wrote it? - he continued, dictating to the clerk, - Kiev Grenadier, Podolsk... - You won’t have time, your honor, - the clerk answered disrespectfully and angrily, looking back at Kozlovsky. At that time, Kutuzov’s animatedly dissatisfied voice was heard from behind the door, interrupted by another, unfamiliar voice. By the sound of these voices, by the inattention with which Kozlovsky looked at him, by the irreverence of the exhausted clerk, by the fact that the clerk and Kozlovsky were sitting so close to the commander-in-chief on the floor near the tub, and by the fact that the Cossacks holding the horses laughed loudly under window of the house - from all this, Prince Andrei felt that something important and unfortunate was about to happen. Prince Andrei urgently turned to Kozlovsky with questions. “Now, prince,” said Kozlovsky. – Disposition to Bagration. -What about capitulation? - There is none; orders for battle have been made. Prince Andrei headed towards the door from behind which voices were heard. But just as he wanted to open the door, the voices in the room fell silent, the door opened of its own accord, and Kutuzov, with his aquiline nose on his plump face, appeared on the threshold. Prince Andrei stood directly opposite Kutuzov; but from the expression of the commander-in-chief’s only seeing eye it was clear that thought and concern occupied him so much that it seemed to obscure his vision. He looked directly at the face of his adjutant and did not recognize him. - Well, have you finished? – he turned to Kozlovsky. - Right this second, Your Excellency. Bagration, a short man with an oriental type of firm and motionless face, a dry, not yet old man, followed the commander-in-chief. “I have the honor to appear,” Prince Andrei repeated quite loudly, handing over the envelope. - Oh, from Vienna? Fine. After, after! Kutuzov went out with Bagration onto the porch. “Well, prince, goodbye,” he said to Bagration. - Christ is with you. I bless you for this great feat. Kutuzov's face suddenly softened, and tears appeared in his eyes. He pulled Bagration to him with his left hand, and with his right hand, on which there was a ring, apparently crossed him with a familiar gesture and offered him a plump cheek, instead of which Bagration kissed him on the neck. - Christ is with you! – Kutuzov repeated and walked up to the carriage. “Sit down with me,” he said to Bolkonsky. – Your Excellency, I would like to be useful here. Let me stay in the detachment of Prince Bagration.