This term has other meanings, see Klobuk (meanings).

Klobuk

(from the Turkic cap -

hat

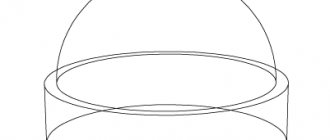

) is the vestment (clothing) of a monk of the minor schema worn on the head in Orthodoxy. It symbolizes the crown of thorns of Jesus Christ - the “garment of humility” and the “helmet of salvation” (Eph. 6:17), protecting from the “arrows of the evil one” (Eph. 6:16). It consists of a kamilavka (a cylinder with cut edges) and a “basket” (a blanket made of silk or other fabric of the same color as the kamilavka), attached to the kamilavka and ending with three long ends that go down the shoulders and back to the waist.

Story

The time of the appearance of the hood in the vestments of monks cannot be determined with accuracy, but it appeared very early. The Slavic name “hood” corresponds to the “title” among the Greeks. The modern form of the kamilavka is of late origin and was taken by the Russian Church from the Greeks in the era of Patriarch Nikon (XVII century). The cover of a kamilavka in ancient times was called maforium (modified word omophorion: ωμοζ - shoulder and φέρω - burden), in modern usage it is called “basting” or “kukul”. In ancient times, this cover was not made of light material, as it is now, but of dense material to protect the head during bad weather. The division of the veil into three ends was also borrowed by Russian monasticism from the Greek and had a purely practical purpose: monks have long had the custom of tying the ends of the veil under the chin in cold and windy weather, and also so that the hood, which is removed at moments of worship specified by the Rule, does not occupy hands

The hood has the symbolic meaning of “helmet of salvation” and “veil of obedience.” In a man's hood, the lower part of the veil (markings) is divided into three long ends, signifying the Trinity grace that covers the thoughts of the monk. The stitched edges of the middle part symbolize the ship, and the two outer parts symbolize the oars. The basting of the female hood descends like a continuous rectangular veil without divisions. Russian nuns wear black hoods on their heads, as well as black skufia and kamilavka only on top of black apostolniks.

Monastics in holy orders wear a hood, both during worship and outside of it. In the Russian tradition, a bishop's hood does not differ from an ordinary monastic hood; archbishops wear a black hood with a cross sewn on it (usually made of precious metals or diamonds)[1], metropolitans wear a white hood with a cross sewn on it. Previously, the diamond cross on the hood of archbishops and metropolitans was a reward.

In the Athonite hood the basting is removable. At certain moments of the service, designated for the removal of the hood, the markings are removed from the Athonite hood, and the head remains covered.

Literal and symbolic meaning

Portrait of St. Ambrose of Optina in a hood

The hood is part of the clothing (headdress) of a monk initiated into the minor schema. Externally, it is a cylinder (kamilavka) expanding upward with three wide black ribbons descending onto the back. The name “hood” itself, according to various opinions, comes from the Greek word “kidaris” - “hat”.

The symbolic meaning of the hood follows from the prayers for the rite of tonsure into the minor schema. Where it is called the helmet of salvation and the cover of obedience. It is also considered an image of the Savior's crown of thorns.

The meaning of these symbols becomes clear from the following words of the Apostle Paul:

“Put on the whole armor of God, so that you can stand against the wiles of the devil, because our struggle is not against flesh and blood, but against the principalities, against the powers, against the rulers of the darkness of this world, against the spiritual forces of wickedness in the heavenly places. For this purpose, take on the whole armor of God, so that you may be able to withstand on the evil day and, having done everything, to stand. Stand therefore, having your loins girded with truth, and having put on the breastplate of righteousness, and having shod your feet with the preparation of the gospel of peace; and above all, take the shield of faith, with which you will be able to quench all the fiery arrows of the evil one; and take the helmet of salvation, and the sword of the Spirit, which is the Word of God” (Eph. 6:11-17).

A monk at his core is a warrior of Christ, who first of all needs to fight the devil and his demons. There is such a story from an ancient patericon. A certain layman, by God's help, heard how demons reported to Satan about the atrocities they had committed.

One reported that he spent a week or a month organizing a mass brawl in a certain place in which tens or hundreds of people died. But Satan cursed him and drove him away. Another said that he “worked” for a whole year and organized a war in which many thousands of soldiers died. But the prince of darkness drove away this one too with abuse and beatings. Finally, the third said that he “worked” for forty years and seduced a monk. Then Satan embraced this demon, called him his best servant and treated him in every possible way.

From this it is clear what the significance of a monk is as the very first warrior of Christ in spiritual warfare! By the way, according to that patericon, the layman who heard this satanic dialogue after this became a monk.

But, as the Apostle Paul noted (Eph. 6: 11-17), if ordinary soldiers put on armor and take on various weapons, a monk should do the same. The only difference is that they accept material weapons, while the monk accepts spiritual ones. In this sense, the hood he wears, symbolically meaning the helmet of salvation (Eph. 6: 17) and the cover of obedience, directs him to the following virtues.

First, to prudence. As the founder of monasticism, the Monk Anthony the Great, said, many took upon themselves great feats, but fell because they lacked prudence. If someone does not have such virtue, then, secondly, he should surrender himself to unconditional obedience to an experienced elder.

The main symbolic meaning of the hood as a monk’s crown of thorns, in my opinion, is as follows. Thus, a monk takes on a number of vows (celibacy, non-covetousness, obedience), which are burdensome for a carnal person. Of course, the fulfillment of these vows is a difficult feat and work, for “from the days of John the Baptist until now, the kingdom of heaven suffers violence, and those who use force take it” (Matthew 11: 12).

But I think this is not the most important work of a monk. Of course, he works, but not in vain. As he mortifies his flesh, his spirit flourishes more and more and his spiritual eyes open, allowing him to see the other world invisible with ordinary eyes.

However, a very unpleasant surprise awaits him here too. As Saint Ignatius (Brianchaninov) explains this: we, people, are fallen creatures. Therefore, when this other world begins to open up to us, the first thing we see is the world of fallen spirits. Which, of course, tempt everyone. But they tempt us, living in the world, invisibly, and the ascetic monks in the most visible way!

The lives of saints and patericon are full of these stories about the fierce battles of monks with the forces of darkness that appear to them in a visible image. What the ancient fathers did not experience from them: the most terrible threats and the dirtiest abuse, and expulsions, and beatings, and much more. But having endured all this to the end, they were saved! And their helmet of salvation helps them with this.

Patriarchal hoods

In the Local Orthodox Churches there are various traditions of wearing patriarchal hoods. Thus, in the churches of Constantinople, Alexandria, Antioch, and Jerusalem, the patriarchs, like all bishops, wear a simple black hood, the same as all monastics. In the Russian Church, the Primate wears a spherical white hood that is different from other bishops. In the Georgian Church, the Catholicos-Patriarch also wears a spherical hood (outwardly similar to the doll of the Patriarch of Moscow and All Rus'), but black and without a cross on the makovets. The patriarchs of the Serbian, Romanian and Bulgarian churches, in turn, wear white hoods, similar to those worn by the metropolitans of the Russian Orthodox Church.

Fyodor Solntsev, a Russian artist, writes: “The difference between the patriarchal hoods and the metropolitan ones were the images of Deesis and cherubs sewn on them, and their cross was also placed on the crown. Although Metropolitan Eugene claims that before Patriarch Nikon, hoods were without St. icons and without the prayers with which the Novgorod archbishops wore them; however, on the hood of Patriarch Philaret we also see St. icons and exclamations. This bedspread was usually either scaly damask or knitted silk; it was decorated with pearls and precious stones; the images on it were embroidered with silk or painted with niello on silver and gold beads, or cloaks. According to their purpose and time of use, hoods were of large attire, which were worn on major holidays, medium and smaller attire, ordinary, or everyday; then warm ones made from fox wombs, covered with white velvet. The kaptyr, or kamilavka, was low-lying, hemispherical, similar to a skufia. From Nikon's time there was noticeably more splendor and significant decorations that he liked to give to his rank; Then the Greek, so-called horned hoods came into use. At the Council of 1675, this hierarchical distinction was defined as follows: “The Patriarch wears a white hood on great holidays, with a cross mounted at the top, and lowered images of miracle workers at the ends. On other days, Seraphim and crosses are worn on the hoods of those who have in advance. Have the patriarchal kamilav, even if it is white in appearance, from Jacob or things, according to the custom of our All-Russian country, exactly with the invasion of the Cherub, and moreover, sincerely have our image of the cross.”

Literature

- White hood // Encyclopedic Dictionary of Brockhaus and Efron: in 86 volumes (82 volumes and 4 additional). - St. Petersburg, 1890-1907.

- Robes of the clergy // Handbook of the clergy. - M.: Publishing Council of the Russian Orthodox Church.

| Dictionaries and encyclopedias |

|

| Orthodox vestments (everyday and liturgical) | |||

| Epitrakhil Kamilavka Kaptyr Cowl Cross with decorations Doll Mantle Miter Gaiter Pectoral cross Omophorion Orar Mace Panagia Paraman Polistavrion Cassock Cassock Handguards Belt Cassock Sakkos Tablets Skufia Surplice Felonne Rosary | |||

White hood

White hoods with a cross are reserved for metropolitans and the patriarch. The patriarchal hood (doll) has a number of differences: the shape is in the form of a spherical cap, there is a cross on the makovtsa (top), all sides are decorated with icons, and seraphims are embroidered in gold at the ends of the hood. The Metropolitan wears a white hood with a cross.

The first bishop to receive the honor of wearing a white hood was Archbishop Vasily of Novgorod and Pskov (1329-1352), to whom the Patriarch of Constantinople sent cross vestments and a white hood.

In 1564, the Moscow Local Council adopted a statute on the right of the Moscow Metropolitan to wear a white hood. After the establishment of the patriarchate in Russia in 1589, the Patriarchs of Moscow and All Rus' began to wear a white hood.

The white hood of the Novgorod archbishop is the subject of a special legend - the Tale of the White hood. Similar to the story of the Kingdom of Babylon, which figuratively represents the transfer of secular power from Babylon to Constantinople and from there to the Russian prince, this legend tells of the transfer of a symbol of spiritual power from Rome to Constantinople, then to Novgorod.

In 1667, the legend was condemned by the Great Moscow Cathedral as “false and wrong” and written by Dmitry Tolmach “from the wind of his head.”

Excerpt characterizing Klobuk

“Sit down, Natasha, maybe you’ll see him,” said Sonya. Natasha lit the candles and sat down. “I see someone with a mustache,” said Natasha, who saw her face. “Don’t laugh, young lady,” Dunyasha said. With the help of Sonya and the maid, Natasha found the position of the mirror; her face took on a serious expression and she fell silent. She sat for a long time, looking at the row of receding candles in the mirrors, assuming (based on the stories she had heard) that she would see the coffin, that she would see him, Prince Andrei, in this last, merging, vague square. But no matter how ready she was to mistake the slightest spot for the image of a person or a coffin, she saw nothing. She began to blink frequently and moved away from the mirror. - Why do others see, but I don’t see anything? - she said. - Well, sit down, Sonya; “Nowadays you definitely need it,” she said. – Only for me... I’m so scared today! Sonya sat down at the mirror, adjusted her position, and began to look. “They’ll definitely see Sofya Alexandrovna,” Dunyasha said in a whisper; - and you keep laughing. Sonya heard these words, and heard Natasha say in a whisper: “And I know what she will see; she saw last year too. For about three minutes everyone was silent. “Certainly!” Natasha whispered and didn’t finish... Suddenly Sonya moved away the mirror she was holding and covered her eyes with her hand. - Oh, Natasha! - she said. – Did you see it? Did you see it? What did you see? – Natasha screamed, holding up the mirror. Sonya didn’t see anything, she just wanted to blink her eyes and get up when she heard Natasha’s voice saying “definitely”... She didn’t want to deceive either Dunyasha or Natasha, and it was hard to sit. She herself did not know how or why a cry escaped her when she covered her eyes with her hand. – Did you see him? – Natasha asked, grabbing her hand. - Yes. Wait... I... saw him,” Sonya said involuntarily, not yet knowing who Natasha meant by the word “him”: him - Nikolai or him - Andrey. “But why shouldn’t I say what I saw? After all, others see! And who can convict me of what I saw or did not see? flashed through Sonya's head. “Yes, I saw him,” she said. - How? How? Is it standing or lying down? - No, I saw... Then there was nothing, suddenly I see that he is lying. – Andrey is lying down? He is sick? – Natasha asked, looking at her friend with fearful, stopped eyes. - No, on the contrary, - on the contrary, a cheerful face, and he turned to me - and at that moment as she spoke, it seemed to her that she saw what she was saying. - Well, then, Sonya?... - I didn’t notice something blue and red... - Sonya! when will he return? When I see him! My God, how I’m afraid for him and for myself, and for everything I’m afraid...” Natasha spoke, and without answering a word to Sonya’s consolations, she went to bed and long after the candle had been put out, with her eyes open, she lay motionless on the bed and looked at the frosty moonlight through the frozen windows. Soon after Christmas, Nikolai announced to his mother his love for Sonya and his firm decision to marry her. The Countess, who had long noticed what was happening between Sonya and Nikolai and was expecting this explanation, silently listened to his words and told her son that he could marry whomever he wanted; but that neither she nor his father would give him his blessing for such a marriage. For the first time, Nikolai felt that his mother was unhappy with him, that despite all her love for him, she would not give in to him. She, coldly and without looking at her son, sent for her husband; and when he arrived, the countess wanted to briefly and coldly tell him what was the matter in the presence of Nicholas, but she could not resist: she cried tears of frustration and left the room. The old count began to hesitantly admonish Nicholas and ask him to abandon his intention. Nicholas replied that he could not change his word, and the father, sighing and obviously embarrassed, very soon interrupted his speech and went to the countess. In all his clashes with his son, the count was never left with the consciousness of his guilt towards him for the breakdown of affairs, and therefore he could not be angry with his son for refusing to marry a rich bride and for choosing the dowryless Sonya - only in this case did he more vividly remember what, if things weren’t upset, it would be impossible to wish for a better wife for Nikolai than Sonya; and that only he and his Mitenka and his irresistible habits are to blame for the disorder of affairs. The father and mother no longer spoke about this matter with their son; but a few days after this, the countess called Sonya to her and with cruelty that neither one nor the other expected, the countess reproached her niece for luring her son and for ingratitude. Sonya, silently with downcast eyes, listened to the countess’s cruel words and did not understand what was required of her. She was ready to sacrifice everything for her benefactors. The thought of self-sacrifice was her favorite thought; but in this case she could not understand to whom and what she needed to sacrifice. She could not help but love the Countess and the entire Rostov family, but she also could not help but love Nikolai and not know that his happiness depended on this love. She was silent and sad and did not answer. Nikolai, as it seemed to him, could not bear this situation any longer and went to explain himself to his mother. Nikolai either begged his mother to forgive him and Sonya and agree to their marriage, or threatened his mother that if Sonya was persecuted, he would immediately marry her secretly. The countess, with a coldness that her son had never seen, answered him that he was of age, that Prince Andrei was marrying without his father’s consent, and that he could do the same, but that she would never recognize this intriguer as her daughter. Exploded by the word intriguer, Nikolai, raising his voice, told his mother that he never thought that she would force him to sell his feelings, and that if this was so, then this would be the last time he spoke... But he did not have time to say that decisive word, which, judging by the expression on his face, his mother was waiting in horror and which, perhaps, would forever remain a cruel memory between them. He did not have time to finish, because Natasha, with a pale and serious face, entered the room from the door where she had been eavesdropping. - Nikolinka, you are talking nonsense, shut up, shut up! I’m telling you, shut up!.. – she almost shouted to drown out his voice. “Mom, my dear, this is not at all because... my poor darling,” she turned to the mother, who, feeling on the verge of breaking, looked at her son with horror, but, due to stubbornness and enthusiasm for the struggle, did not want and could not give up. “Nikolinka, I’ll explain it to you, you go away - listen, mother dear,” she said to her mother. Her words were meaningless; but they achieved the result she was striving for. The countess, sobbing heavily, hid her face in her daughter's chest, and Nikolai stood up, grabbed his head and left the room. Natasha took up the matter of reconciliation and brought it to the point that Nikolai received a promise from his mother that Sonya would not be oppressed, and he himself made a promise that he would not do anything secretly from his parents. With the firm intention, having settled his affairs in the regiment, to resign, come and marry Sonya, Nikolai, sad and serious, at odds with his family, but, as it seemed to him, passionately in love, left for the regiment in early January. After Nikolai's departure, the Rostovs' house became sadder than ever. The Countess became ill from mental disorder. Sonya was sad both from the separation from Nikolai and even more from the hostile tone with which the countess could not help but treat her. The Count was more than ever concerned about the bad state of affairs, which required some drastic measures. It was necessary to sell a Moscow house and a house near Moscow, and to sell the house it was necessary to go to Moscow. But the countess’s health forced her to postpone her departure from day to day.