Meaning of the term

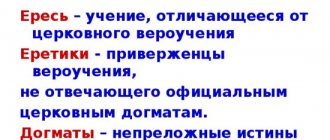

Heresy is a deliberate distortion of Orthodox dogma.

In ancient Greek, the word heresy (ancient Greek αἵρεσις) meant “choice,” “current,” or “direction.” The concept of “heresy” in Judeo-Hellenistic culture denoted religious or philosophical trends, trends and schools. For example, the religious and political parties of the Pharisees and Sadducees are called heresies in Acts (Acts 5:17, 15:5, 26:5).

In the New Testament Apostolic Epistles, the concept of “heresy” takes on a different semantic connotation. It begins to be opposed to correct dogma and turns into a denial of the truth of Divine Revelation. This is no longer just a direction or current of thought, but a conscious desire to distort the foundations of Christian doctrine, and, therefore, to deprive a person of the possibility of salvation in eternity.

The essence of heretical teachings was perfectly expressed by St. Basil the Great. Following all the holy fathers, he believed that heretics should include those alienated from Orthodoxy in the faith itself, distorting one or more dogmas set forth in the Creed or any sacred tradition and institution sanctified by the original and long-term use in the Church. “They called heretics those who were completely rejected and alienated in the faith itself,” says St. Vasily about the opinion of St. Fathers. “For here there is a clear difference in the very belief in God.”

Following the interpretation of the position of St. Basil the Great, given by the outstanding Orthodox commentator on canon law John Zonara, “heretics are all those who think contrary to the Orthodox faith, no matter how long ago, no matter how recently they were excommunicated from the Church, no matter how old or new heresies they adhere to.”

An expert in church law, Bishop Nikodim (Milash) of Dalmatia-Istra, wrote that heresy as “a teaching contrary to the Orthodox faith, however, should not necessarily concern the foundations of the Orthodox faith in order for a given person to be considered a heretic - it is enough that he sins at least in one dogma, and by virtue of this it is already a heretic.”

The essence of heresy is deeply revealed by St. Ignatius Brianchaninov: “Heresy is a covert rejection of Christianity. When people began to abandon idolatry, due to its obvious absurdity, and come to the knowledge and confession of the Redeemer; when all the efforts of the devil to support idolatry among people remained in vain; Then he invented heresies, and through heresy, while preserving for those who adhered to it the name and some appearance of Christians, he not only took Christianity away from them, but also replaced it with blasphemy.”

As sectologist A.L. Dvorkin rightly notes, “the word heretic... means a person who makes an arbitrary choice under the guidance of his own ideas and desires. This term is Christian in origin, and, therefore, in order to become a heretic in the patristic sense of the word, a person must initially have been in the truth.”

In ascetic terms, heresy is an extreme degree of delusional opinion, which can periodically renew itself as a typologically stable captivity of the mind. Heresy combines many passionate states: opinion, self-delusion, pride, self-will, etc.

Excerpt characterizing the List of Christian heresies

The glow of the first fire that started on September 2nd was watched from different roads by fleeing residents and retreating troops with different feelings. That night the Rostovs' train stood in Mytishchi, twenty miles from Moscow. On September 1, they left so late, the road was so cluttered with carts and troops, so many things had been forgotten, for which people had been sent, that that night it was decided to spend the night five miles outside Moscow. The next morning we set off late, and again there were so many stops that we only got to Bolshie Mytishchi. At ten o'clock the gentlemen of the Rostovs and the wounded who were traveling with them all settled in the courtyards and huts of the large village. The people, the Rostovs' coachmen and the wounded's orderlies, having removed the gentlemen, had dinner, fed the horses and went out onto the porch. In the next hut lay Raevsky’s wounded adjutant, with a broken hand, and the terrible pain he felt made him moan pitifully, without ceasing, and these groans sounded terribly in the autumn darkness of the night. On the first night, this adjutant spent the night in the same courtyard in which the Rostovs stood. The Countess said that she could not close her eyes from this groan, and in Mytishchi she moved to a worse hut just to be away from this wounded man. One of the people in the darkness of the night, from behind the high body of a carriage standing at the entrance, noticed another small glow of a fire. One glow had been visible for a long time, and everyone knew that it was Malye Mytishchi that was burning, lit by Mamonov’s Cossacks. “But this, brothers, is a different fire,” said the orderly. Everyone turned their attention to the glow. “But, they said, Mamonov’s Cossacks set Mamonov’s Cossacks on fire.” - They! No, this is not Mytishchi, this is further away. - Look, it’s definitely in Moscow. Two of the people got off the porch, went behind the carriage and sat down on the step. - This is left! Of course, Mytishchi is over there, and this is in a completely different direction. Several people joined the first. “Look, it’s burning,” said one, “this, gentlemen, is a fire in Moscow: either in Sushchevskaya or in Rogozhskaya.” No one responded to this remark. And for quite a long time all these people silently looked at the distant flames of a new fire flaring up. The old man, the count's valet (as he was called), Danilo Terentich, approached the crowd and shouted to Mishka. - What haven’t you seen, slut... The Count will ask, but no one is there; go get your dress. “Yes, I was just running for water,” said Mishka. – What do you think, Danilo Terentich, it’s like there’s a glow in Moscow? - said one of the footmen. Danilo Terentich did not answer anything, and for a long time everyone was silent again. The glow spread and swayed further and further. “God have mercy!.. wind and dryness...” the voice said again. - Look how it went. Oh my God! You can already see the jackdaws. Lord, have mercy on us sinners! - They'll probably put it out. -Who should put it out? – the voice of Danila Terentich, who had been silent until now, was heard. His voice was calm and slow. “Moscow is, brothers,” he said, “she is mother squirrel...” His voice broke off, and he suddenly sobbed like an old man. And it was as if everyone was waiting for just this in order to understand the meaning that this visible glow had for them. Sighs, words of prayer and the sobbing of the old count's valet were heard. The valet, returning, reported to the count that Moscow was burning. The Count put on his robe and went out to have a look. Sonya, who had not yet undressed, and Madame Schoss came out with him. Natasha and the Countess remained alone in the room. (Petya was no longer with the family; he went forward with his regiment, marching to Trinity.) The Countess began to cry when she heard the news of the fire in Moscow. Natasha, pale, with fixed eyes, sitting under the icons on the bench (in the very place where she sat when she arrived), did not pay any attention to her father’s words. She listened to the incessant moaning of the adjutant, heard three houses away. - Oh, what a horror! - said Sonya, cold and frightened, returned from the yard. - I think all of Moscow will burn, a terrible glow! Natasha, look now, you can see from the window from here,” she said to her sister, apparently wanting to entertain her with something. But Natasha looked at her, as if not understanding what they were asking her, and again stared at the corner of the stove. Natasha had been in this state of tetanus since this morning, ever since Sonya, to the surprise and annoyance of the Countess, for some unknown reason, found it necessary to announce to Natasha about Prince Andrei’s wound and his presence with them on the train. The Countess became angry with Sonya, as she rarely became angry. Sonya cried and asked for forgiveness and now, as if trying to make amends for her guilt, she never stopped caring for her sister. “Look, Natasha, how terribly it burns,” said Sonya. – What’s burning? – Natasha asked. - Oh, yes, Moscow. And as if in order not to offend Sonya by refusing and to get rid of her, she moved her head to the window, looked so that, obviously, she could not see anything, and again sat down in her previous position. -Have you not seen it? “No, really, I saw it,” she said in a voice pleading for calm. Both the Countess and Sonya understood that Moscow, the fire of Moscow, whatever it was, of course, could not matter to Natasha. The Count again went behind the partition and lay down. The Countess approached Natasha, touched her head with her inverted hand, as she did when her daughter was sick, then touched her forehead with her lips, as if to find out if there was a fever, and kissed her. -You're cold. You're shaking all over. You should go to bed,” she said. - Go to bed? Yes, okay, I'll go to bed. “I’ll go to bed now,” Natasha said. Since Natasha was told this morning that Prince Andrei was seriously wounded and was going with them, only in the first minute she asked a lot about where? How? Is he dangerously injured? and is she allowed to see him? But after she was told that she could not see him, that he was seriously wounded, but that his life was not in danger, she, obviously, did not believe what she was told, but was convinced that no matter how much she said, she would be answer the same thing, stopped asking and talking. All the way, with big eyes, which the countess knew so well and whose expression the countess was so afraid of, Natasha sat motionless in the corner of the carriage and now sat in the same way on the bench on which she sat down. She was thinking about something, something she was deciding or had already decided in her mind now - the countess knew this, but what it was, she did not know, and this frightened and tormented her. - Natasha, undress, my dear, lie down on my bed. (Only the countess alone had a bed made on the bed; m me Schoss and both young ladies had to sleep on the floor on the hay.) “No, mother, I’ll lie down here on the floor,” Natasha said angrily, went to the window and opened it. The adjutant’s groan from the open window was heard more clearly. She stuck her head out into the damp air of the night, and the countess saw how her thin shoulders shook with sobs and beat against the frame. Natasha knew that it was not Prince Andrei who was moaning. She knew that Prince Andrei was lying in the same connection where they were, in another hut across the hallway; but this terrible incessant groan made her sob. The Countess exchanged glances with Sonya. “Lie down, my dear, lie down, my friend,” said the countess, lightly touching Natasha’s shoulder with her hand. - Well, go to bed. “Oh, yes... I’ll go to bed now,” said Natasha, hastily undressing and tearing off the strings of her skirts. Having taken off her dress and put on a jacket, she tucked her legs in, sat down on the bed prepared on the floor and, throwing her short thin braid over her shoulder, began to braid it. Thin, long, familiar fingers quickly, deftly took apart, braided, and tied the braid. Natasha's head turned with a habitual gesture, first in one direction, then in the other, but her eyes, feverishly open, looked straight and motionless. When the night suit was finished, Natasha quietly sank down onto the sheet laid on the hay on the edge of the door. “Natasha, lie down in the middle,” said Sonya. “No, I’m here,” Natasha said. “Go to bed,” she added with annoyance. And she buried her face in the pillow. The Countess, m me Schoss and Sonya hastily undressed and lay down. One lamp remained in the room. But in the yard it was getting brighter from the fire of Malye Mytishchi, two miles away, and the drunken cries of the people were buzzing in the tavern, which Mamon’s Cossacks had smashed, on the crossroads, on the street, and the incessant groan of the adjutant was heard. Natasha listened for a long time to the internal and external sounds coming to her, and did not move. She heard first the prayer and sighs of her mother, the cracking of her bed under her, the familiar whistling snoring of m me Schoss, the quiet breathing of Sonya. Then the Countess called out to Natasha. Natasha did not answer her. “He seems to be sleeping, mom,” Sonya answered quietly. The Countess, after being silent for a while, called out again, but no one answered her. Soon after this, Natasha heard her mother's even breathing. Natasha did not move, despite the fact that her small bare foot, having escaped from under the blanket, was chilly on the bare floor. As if celebrating victory over everyone, a cricket screamed in the crack. The rooster crowed far away, and loved ones responded. The screams died down in the tavern, only the same adjutant's stand could be heard. Natasha stood up. - Sonya? are you sleeping? Mother? – she whispered. No one answered. Natasha slowly and carefully stood up, crossed herself and stepped carefully with her narrow and flexible bare foot onto the dirty, cold floor. The floorboard creaked. She, quickly moving her feet, ran a few steps like a kitten and grabbed the cold door bracket. It seemed to her that something heavy, striking evenly, was knocking on all the walls of the hut: it was her heart, frozen with fear, with horror and love, beating, bursting. She opened the door, crossed the threshold and stepped onto the damp, cold ground of the hallway. The gripping cold refreshed her. She felt the sleeping man with her bare foot, stepped over him and opened the door to the hut where Prince Andrei lay. It was dark in this hut. In the back corner of the bed, on which something was lying, there was a tallow candle on a bench that had burned out like a large mushroom. Natasha, in the morning, when they told her about the wound and the presence of Prince Andrei, decided that she should see him. She did not know what it was for, but she knew that the meeting would be painful, and she was even more convinced that it was necessary. All day she lived only in the hope that at night she would see him. But now, when this moment came, the horror of what she would see came over her. How was he mutilated? What was left of him? Was he like that incessant groan of the adjutant? Yes, he was like that. He was in her imagination the personification of this terrible groan. When she saw an obscure mass in the corner and mistook his raised knees under the blanket for his shoulders, she imagined some kind of terrible body and stopped in horror. But an irresistible force pulled her forward. She carefully took one step, then another, and found herself in the middle of a small, cluttered hut. In the hut, under the icons, another person was lying on the benches (it was Timokhin), and two more people were lying on the floor (these were the doctor and the valet).

The main danger of heresy

They said about Abba Agathon: “Some people came to him, having heard that he had great prudence. Wanting to test him to see if he will get angry, they ask him: “Are you Agathon? We have heard about you that you are a fornicator and a proud man.” “Yes, it’s true,” he answered. They again ask him: “Are you, Agathon, a slanderer and an empty talker?” “I am,” he answered. And they also say to him: “Are you, Agathon, a heretic?” “No, I am not a heretic,” he answered. Then they asked him: “Tell us, why did you agree to everything they said to you, but couldn’t bear the last word?” He answered them: “I admit the first vices in myself, for this recognition is useful to my soul, and recognizing myself as a heretic means excommunication from God , and I do not want to be excommunicated from my God.” Having heard this, they marveled at his prudence and walked away, having received edification.”

(Ancient Patericon. 1914. P. 27. No. 4.)

Heresies from the point of view of various non-Orthodox Christian denominations

From the point of view of traditional faiths[1]

| Exercises | Catholicism | Traditional Protestantism | Ancient Eastern churches | ||||

| Lutheranism | Calvinism | Anglicanism | Assyrian Church of the East | Ancient Eastern "Orthodox" Churches | |||

| Early Christian | Gnosticism | Yes, heresy | |||||

| Montanism | Yes, heresy | ||||||

| Antitrinitarian | Arianism | Yes, heresy[2] | |||||

| Macedonianism | Yes, heresy | ||||||

| Tritheism | Yes, heresy | ||||||

| Filioque | No, not heresy | No, not heresy (with reservations) | Yes, heresy | ||||

| Modalism | Yes, heresy | ||||||

| Pre-Chalcedonian Christological | Apollinarianism | Yes, heresy | |||||

| Miaphysitism | Yes, heresy | No, not heresy (with reservations) | |||||

| Nestorianism | Yes, heresy | No, not heresy | Yes, heresy | ||||

| Monophysitism | Yes, heresy | ||||||

| Late Byzantine | Monothelitism | Yes, heresy | No, not heresy (with reservations) | ||||

| Iconoclasm | Yes, heresy | No, not heresy | Yes, heresy | ||||

| Traditional Roman | Papism | No, not heresy | Yes, heresy | ||||

| Pan-Protestant | About Justification by Faith Alone | Yes, heresy | No, not heresy | Yes, heresy | |||

| On the Inspiration of Holy Scripture Only | Yes, heresy | No, not heresy | Yes, heresy | ||||

| On the disrespect of saints | Yes, heresy | No, not heresy | Yes, heresy | ||||

| Mariological | About the Immaculate Conception of the Virgin Mary | No, not heresy | Yes, heresy | ||||

| About the taking into Heavenly Glory of the Virgin Mary | No, not heresy | Yes, heresy | |||||

Heresies in history

The emergence of heresies was predicted by the Apostle Peter: “There were also false prophets among the people, just as there will be false teachers among you, who will introduce destructive heresies and, denying the Lord who bought them, bring upon themselves swift destruction” (2 Pet. 2:1). The Apostle Paul places heresy on the same level as the sin of witchcraft and idolatry (Gal. 5:20).

The early Christian Church strictly monitored the purity of its doctrine, resolutely opposing itself to all distortions of Christianity. That is why the term Orthodoxy (Greek Όρθοδοξία - Orthodoxy, orthodoxy, correct knowledge, judgment) was assigned to it.

The term Orthodoxy, which has been spreading since the 2nd century, means the faith of the entire Church, in contrast to the various teachings of heretical communities, for which the word heterodoxy was used (έτεροδοξία - another teaching, knowledge different from the correct one).

Initially, Gnostics were called heretics, although Simon the Magus is considered the founder of heresies (Acts 8:9). The first period includes such heresies as Ebionism, Cerinthianism, Elkesaism, Docetism, Manichaeism, Montanism, and Chiliasm.

Triadological heresies : monarchianism and Arianism, condemned at the First and Second Ecumenical Councils. The list of heresies condemned at the Second Ecumenical Council also includes: Eunomians, Anomeans, Eudoxians, Semi-Arians, or Doukhobors (Macedonians), Sabellians, Photinians, Apolinarians.

Christological heresies : Nestorianism (Eutychianism), Monophysitism, Monothelitism, condemned at subsequent councils, as well as iconoclasm, condemned at the 7th Sun. The cathedral was practically a repetition and development of the ancients. During the Reformation, the rationalism of the anti-Trinitarians was revived (Servetus, Socinians, etc., in Russia - Theodosius Kosoy). The Adoptians were a modification of the Nestorians, and the Paulicians and Bogomils were a variation of Manichaeism. In the Middle Ages, the Albigensians, Cathars, and Patarens appeared in the West as echoes of Manichaeism. In the 12th century The Waldenses arose - a mixture of pietism and rationalism.

Notes

- Archpriest Maxim Kozlov.

Orthodoxy and heterodoxy. - Moscow: Nikeya, 2010. - 160 pages. Offset paper p. — ISBN 978-5-91761-039-9. - Orthodox encyclopedia. Volume III. / S.A.Isaev. - 1. - Augsburg Confession: Central Scientific Center "Orthodox Encyclopedia", 2001. - P. 687-690. — ISBN 5-89572-008-0.

Trinitarian Tritheism · Monarchianism (Adoptionism · Modalism · Sabellianism) · Arianism (Anomaeism, Omii, Omiusians) · Macedonianism · Agnoites · Patripassians · Triscilids Christological Theopaschism · Apollinarism · Monophysitism · Aphthardocetism · Agnoites · Isochrists · Monothelitism · Nestorianism · Monoenergism · Christolites Ecclesiological Montanism · Donatism · Novatianism · Phyletism · Branch theory · Others Nazarenes (1st century) · Ebionites · Chiliasm · Psylantropism · Pelagianism · Origenism · Antidicomariamites · Collyridians · Messalianism · Metangismonites · Seleucanians · Proclianites · Patricians · Ascites · Passalorhynchites · Aquarians · Collufians · Florinians · Satannians · Barefoot · Hydropheites · Homuncionites · Ameter ites · Psychopneumone · Adecerdites · Metagenetes · Proto-Destinates · Paternians · Barsanuphytes · Icetes · Gnosimachos · Iliotropites · Phnitopsychites · Agoniclites · Theocathognostos · Ephnophrones · Iphicoproscoptes · Parermineutes · Adelophagi · Rhetorians · Lampetians · Iconoclasm · Hatzizari · Heresy to Judaism people · Strigolniki · Molokans · Nazarenes (XIX century) · Ushkovaizet ·

The sequence of heresies

“In the appearance of heretics who distorted the divine, unchangeable teaching of the Christian Church,” writes E. Smirnov, “there is a certain consistency and system, namely, a transition from the general to the specific. It was to be expected that at first, as a result of the entry into the Church of Jews and pagans who did not want to completely renounce Judaism and paganism and therefore mixed Christian teaching with Jewish views, heretical errors would appear regarding the entire system of Christian teaching, and not just any particular point.

And so it really was: on the one hand, there appeared the Judaizing heretics, also called Ebionites, who sought to merge Christianity with Judaism, even with the subordination of the former to the latter, and on the other, the pagans, or, as they were called in the 2nd century, the Gnostics, and then the Manichaeans, those who sought to form a mixed religious system from the Christian doctrine in combination with the Eastern religious worldview or Greek philosophy.

When the false teachings of these heretics were rejected by the Church and began to become obsolete, they were replaced by other kinds of heresies, which grew on Christian soil. Their subject is the main dogma of Christianity about the trinity of Persons in the Divinity. These are the heresies of the anti-Trinitarians.

In the time that followed, a heresy developed on an even more specific issue: the Divinity of the Second Person of the Holy Trinity. This heresy, known as Arianism, appeared openly already at the beginning of the 4th century.

In the apostolic age we see heretics, Judaizers and pagans. The latter laid the foundation for Gnosticism, which developed especially strongly in the 2nd century. after the times of the apostles."

Content

- 1 Heresies from the point of view of various non-Orthodox Christian denominations

- 2 Heresies from the point of view of the Orthodox Church 2.1 Traditional classification 2.1.1 List of John of Damascus

- 2.1.2 Heresy of iconoclasm

- 2.2.1 Gnostic heresies

Denouncers of heresies

Ancient heretical texts, as a rule, were destroyed, so information about heresies can be gleaned from their denouncers: St. Irenaeus of Lyons, St. Hippolytus of Rome, Tertullian, Origen, St. Cyprian of Carthage, St. Epiphanius of Cyprus (he, together with Irenaeus and Hippolytus, is called hereseologists), Clement of Alexandria, Eusebius Pamphilus, bl. Theodoret of Cyrus, bl. Aurelius Augustine, Euthymius Zigabena.