In the 16th century, the world was mired in the chaos of the Reformation, the instigator of which was Martin Luther. Some called him “a man with the soul of the devil”, others considered him an angel, but today both Protestants and Catholics agree that he was not only right in his judgments, but also changed the history of the West for the better.

Who is Martin Luther

Luther's personality is perceived ambiguously by many.

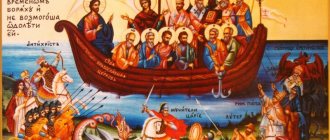

The one who, at a difficult moment in his life, asked St. Anne for help, later became famous for renouncing the cult of saints. Anyone who vowed to take the monastic vow soon abandoned the institution of monasticism. The former faithful son of the Catholic Church turned the entire structure of medieval Catholicism on its head. Being a devoted servant of the Pope, over time he began to identify him with the Antichrist. But at the same time, his controversial personality awakened Christian consciousness in Europe.

Historian R. Baynton

Birth and childhood

On November 10, 1483, a boy was born into the family of Hans and Margaret Luther, who was named Martin. The Luther family was not rich, but the father was very hardworking and strived to provide his family with everything they needed. To do this, he moved from a small Saxon village to Eisleben, where Martin was born, and got a job in the copper mines. After the future reformer was 6 months old, the Luthers moved to Mansfeld, where the family’s financial situation improved sharply, and Hans Luther acquired the status of a wealthy burgher.

Schooling

The first difficulties in life overtook Martin at the age of 7 years. The parents sent their son to study at a city school, which turned out to be almost useless for the talented little genius: during 7 years of study, Martin learned to write, read, and also learned several prayers and the Ten Commandments.

At the age of 14, the boy is transferred to the Franciscan school in Magdeburg. There was not enough money, so Luther and his friends sang under the windows of devout citizens, trying to somehow earn extra money. Then, for the first time, thoughts came to him that he should follow in his father’s footsteps and go to the mines, but a chance meeting with the wife of a wealthy local resident opened the way for the boy to a new life.

Student years

By decision of his parents, in 1501 Martin entered the Faculty of Philosophy at the University of Erfurt. At that time, wealthy citizens sought to give their sons a higher legal education, for which it was necessary to take a course in the “seven liberal arts.”

The teenager had an excellent memory, which allowed him to grasp new knowledge on the fly. He easily mastered complex material and soon became popular among his peers.

After receiving a Master of Arts degree in 1505, Luther began studying law. That same year, against his father's wishes, he entered the Augustinian monastery in Erfurt. This event is preceded by several legends. According to one of them, Martin once found himself in a severe thunderstorm and, in exchange for a miraculous rescue, promised to join the Augustinian Order.

The second says that the future reformer abandoned worldly life due to the sudden death of a close friend and awareness of his own sinfulness.

Service in the monastery

Luther took monastic vows in 1506, and in 1507 he was elevated to the rank of priest. At first, his activities in the holy place had little to do with worship - Martin served the elders, guarded the gates, wound the tower clock and swept the church yard.

Nevertheless, he carefully adhered to these vows, fulfilling every instruction. Immersed in the life of a monk, Martin devoted himself entirely to prayer, using austerities in food, clothing and rest, and later recalled: “If anyone could go to heaven by living a monastic life, it would be me.”

Luther continued to learn and develop. In 1508, on the recommendation of the vicar general, Martin (at that time already Augustine’s brother) was sent to the University of Wittenberg as a teacher of dialectics and physics.

After earning a bachelor's degree in biblical studies, Luther was able to teach theology and was qualified to interpret biblical scriptures. To better understand their meaning, the priest began to study foreign languages.

In 1511, having gone to Rome on business of the order, Luther was greatly impressed by the corruption of the Roman Catholic Church, which gave indulgences for money, and since then his attitude towards the church changed: the priest was overcome by experiences that played a large role in the formation of his views.

Since 1512, Luther received the position of professor of theology, read sermons, painstakingly studied the Bible, and also served as caretaker in 11 monasteries.

Personal life

Contrary to all the canons of the Catholic Church, Luther believed that God cannot forbid people to live in love and continue their family line. Therefore, on June 13, 1525, his wedding took place with Katharina von Bora, a former nun who bore him six children in their marriage. At the time of marriage, the Protestant was 42, and his chosen one was only 26.

The harsh church upbringing and asceticism adopted by the wife made her character strict and stern, which was clearly manifested in the life of the spouses. They chose an abandoned Augustinian monastery as their place of residence. They had no property, but their home was always open to those in need until the moment he died.

Illness and death

Hard work and emotional distress undermined Luther's health. Until his death, he lectured, preached and wrote books, often forgetting about food and healthy sleep. The illness crept up on him unnoticed, at first manifesting itself in dizziness and sudden fainting, but then it became much more serious, and the torment it caused was unbearable.

During his lifetime, Martin admitted that the devil often visited him at night and asked strange questions. The so-called stone disease made him suffer for many years, and Luther desperately asked the Lord for death.

On April 18, 1546, the great reformer passed away. His body was buried in the courtyard of the very church where, according to legend, he once nailed his famous 95 theses.

Long search

Luther was born in 1483 in the German city of Eisleben. His father, a peasant by birth, was first a miner and then became the owner of several foundries. Martin's childhood cannot be called happy. His parents raised him strictly, and many years later he spoke with bitterness about the punishments he was subjected to at that time. Throughout his life, he more than once fell into melancholy and a state of anxiety, which some researchers attribute to the extreme severity of his treatment in childhood and adolescence. At first, things went no better at school, and he later recalled that he was whipped when he did not know his lessons. One should not exaggerate the significance of these early trials and assume that they predetermined the entire future course of Luther’s life; nevertheless, they undoubtedly left a deep imprint on his character.

In July 1505, at the age of almost twenty-two, Luther entered the Augustinian monastery in Erfurt. Several reasons led him to this decision. Two weeks earlier, during a thunderstorm, he was overcome by the fear of death and hell, and he made a promise to St. Anna to become a monk. In his own words, he was brought to the monastery by the difficult conditions in which he grew up. His father intended him to become a lawyer and spared no effort to give him the necessary education. But Luther did not want to be a lawyer, and it is quite possible that, although not fully aware of his motives, he chose the monastic vocation as a kind of compromise between his father’s plans and his own inclinations. Upon learning of this decision, the elder Luther was indignant and for a long time could not forgive his son, believing that he had betrayed his noble life goals. But ultimately, concern for his own salvation brought Luther to the monastery. The thought of salvation and condemnation literally permeated the atmosphere in which he lived. Earthly life is nothing more than a test and preparation for the life to come. It seemed stupid, having become a lawyer, to achieve fame and fortune in this life at the expense of eternal life. Therefore, Luther, as a faithful son of the church, entered the monastery with the firm intention of using the means of salvation offered by the church, the most reliable of which was the monastic life of self-denial.

During his year of novitiate, Luther became convinced that he had made a wise decision—he felt happy and lived at peace with God. The abbots quickly became convinced of his extraordinary abilities and decided that he should become a priest. Subsequently, recalling the feelings that overwhelmed him when he celebrated his first Mass, Luther wrote about the fear that gripped him at the thought that he was holding and offering the very body of Christ. Then he began to experience a feeling of fear more and more often - he considered himself unworthy of God's love and was not sure that his works were enough for salvation. God seemed to him a strict judge - like his father and school teachers - Who on Judgment Day would call him to account and find him to have failed the test. In order to be saved from the wrath of such a God, a person must use all the means of grace offered by the church.

But for such a deeply religious, sincere and passionate person as Luther was, these funds were not enough. It was believed that good deeds and the sacrament of repentance were enough to justify a young monk before God. Luther, however, did not think so. He experienced an overwhelming sense of his own sinfulness, and the more he tried to suppress it, the more aware of the power of sin over himself. The assumption that he was not a good monk or that he led an immoral life is wrong. On the contrary, he strove to strictly fulfill his monastic vows. He constantly punished his body, as the great teachers of monasticism prescribed. He confessed as often as he could. But all this did not weaken his fear of condemnation. To receive forgiveness of sins, one must repent of them, but he was afraid that he might forget about some sin and thereby lose the reward for which he so tirelessly strived. So he spent long hours making lists and analyzing his thoughts and actions, and the more he did this, the more sins he discovered in himself. There were times when, having already left the confessional, he remembered a sin for which he had not repented. Then he was overcome by a feeling of anxiety and despair, for sin is not just conscious actions or thoughts. Sin is a state, a way of life, something much more than individual sins for which a priest can repent. Thus, the very sacrament of repentance, which was supposed to bring relief, in fact further strengthened his sense of his sinfulness and did not help him cope with despair.

His spiritual mentor advised him to read the works of great mystics. As we have already seen, at the end of the medieval period (partly as a reaction to the decay of the church) there was a sharp increase in interest in mystical piety, which offered a different way of approaching God. Luther also decided to follow this path, but not because he doubted the authority of the church, but because he received such advice from his confessor, who represented this authority.

Mysticism, like monasticism earlier, fascinated him for a while. Perhaps here he will find a way to salvation. But this path also soon led him to a dead end. The mystics argued that it is enough for a person to simply love God and that this love gives everything else. Luther took these words as liberation - he no longer had to keep a strict record of all his sins, as he had conscientiously done until now, receiving only a feeling of dissatisfaction and despair as a reward. But he soon realized that loving God is not so easy. If God is like his father and teachers who beat him to the point of bleeding, how can he love such a God? In the end, Luther came to the terrifying conclusion that what he felt for God was not love, but hatred!

It was impossible to escape these questions and thoughts. To be saved, a person must repent of sins, but Luther saw that, despite his best efforts, sin was beyond what he could repent of. According to the mystics, it is enough to love God, but this also did not help much, since Luther was forced to admit that he could not love a just God who demanded an account of all his actions.

At this stage, the confessor, who was also the rector, took a bold step. It was usually believed that a priest experiencing such an internal crisis, as was the case with Luther, could not be a shepherd and teacher. But the confessor decided that Luther should nevertheless fulfill this role. Centuries ago, Jerome escaped temptation through his work on Hebrew texts. Luther faced different challenges than Jerome, but study, teaching, and pastoral duties may have had the same impact on him. Therefore, Luther unexpectedly received an appointment to the position of teacher of Scripture at the newly opened university in the city of Wittenberg.

According to Protestant tradition, during his monastic years Luther did not know the Bible and began to study it only from the time of his conversion or shortly before that. But that's not true. As a monk, he observed the statutory hours of prayer and therefore knew the Psalter by heart. In addition, in 1512, after completing a course that included the study of the Bible, he received the degree of Doctor of Divinity.

Faced with the need to prepare lectures on biblical topics, Luther began to look for a new meaning in the Bible that would give him an answer to his own spiritual quest. In 1513 he began lecturing on the Psalter. Having spent many years reading the psalms, following a yearly cycle of worship based on the major events of the life of Christ, Luther interpreted the psalms from a Christological point of view. When the psalmist spoke in the first person, for Luther this meant that through the words of the psalmist Christ Himself was speaking about Himself. In the Psalter, Luther saw Christ experiencing the same trials as himself. This became the basis for his great discovery. In itself, this would have led Luther to accept the common view that God the Father requires judgment, and God the Son, who loves us, promotes our forgiveness. But Luther studied theology and knew that such a dichotomy in relation to the Divine is unacceptable. Therefore, the comfort he found in Christ's suffering was not enough to relieve his pain and his own suffering.

The great discovery appears to have occurred in 1515, when Luther began to lecture on the Epistle to the Romans. He later stated that the first chapter of this message helped him overcome his difficulties. But it was not easy for him. It was not enough to simply open the Bible and read that “the righteous shall live by faith.” By his own admission, he made this discovery after a long internal struggle and mental suffering, for at the beginning of the verse Rom. 1:17 says that the Gospel “reveals the righteousness [or justice of God’s judgment].” These words mean that the gospel reveals the righteousness—and justice of judgment—of God. But it was difficult for Luther to accept the judgment of God. How can such a message be Good News? In Luther's eyes, the Good News could only be that God does not execute justice, that is, that He does not judge sinners. But to Rome. 1:17 The Good News and God's judgment are inextricably linked.

Luther was disgusted by the words “the righteousness of God,” and he spent days and nights trying to understand the relationship between the two parts of this verse, which first proclaims “the righteousness [of judgment] of God” and then states that “the just shall live by faith.”

The answer was surprising. Luther came to the conclusion that “the judgment of God” did not mean, as he had previously thought, the punishment of sinners. The “truth” or “righteousness” of the righteous does not belong to them, but to God. “The Truth of God” is received by those who live by faith. It is given to them not because they are righteous, not because they fulfill the requirements of the divine legal order, but simply because God desires it. Therefore, Luther's doctrine of "justification by faith" does not imply faith as something that God requires us to achieve in order to then receive a reward for it. It means that faith and justification are God's works, a gift of grace to sinners. Having made this discovery, Luther wrote in the preface to his writings in Latin: “I feel myself born again and see that the gates of heaven have opened before me. All Scripture took on new meaning. From this moment on, the words “God’s truth” no longer frighten me, but, on the contrary, evoke in me inexpressible pleasure as an expression of great love.”

Religious activities

After receiving his Doctor of Bible degree in 1512, Luther began a series of Bible lectures that he preached throughout his life.

Teaching theology and theology

The initial lectures of the founder of Protestantism were devoted to the Psalms. Having worked through it all, Martin showed even then that he was at the top of Bible study in his day.

At that time, the so-called Biblical humanism came into fashion, relating to the humanities - the study of ancient Greek and Latin writers, as well as Hebrew literature. Biblical humanists were interested in a wide range of topics - ancient and classical authors, both ecclesiastical and pagan. In addition, they were very interested in mastering foreign languages. Luther often used their works in his lectures.

Having finished his lectures on the Psalter, Martin took up lectures on the Epistle to the Romans, working through its text from 1515 to 1516.

The following year he lectured on Galatians and published them in 1519. The year 1517 marked the beginning of work on the Epistle to the Hebrews. Towards the end of 1517, the priest became involved in controversy in the church over his 95 Theses, so a second series of lectures had to be started in 1518-1519, as the events of the Reformation piled on him the burden of new affairs.

In 1535, the reformer began a series of lectures on the Book of Genesis, which took him ten years.

Sermons

Luther began his preaching work in the city church of Wittenberg and at first had no intention of going against his native Catholic Church. The parishioners loved him for his eloquence and piety. In his sermons, he often reflected on the relationship between man and God.

For the Roman Church, these relationships were very clear: God addresses people through the Pope, and then down the church hierarchy. Consequently, the Vatican ascribed to itself a monopoly on the interpretation of the Bible and believed that it could punish those who, in its opinion, had violated the biblical commandments.

The Reformer rejected “apostolic mediation” in the relationship between God and man. The highest spiritual authority, according to Luther's teachings, was only the Bible.

After the events of 1524-1525, Luther began to emphasize the lack of education and stupidity of the peasants, speaking of the need to train competent preachers.

The priest set himself the following tasks:

- create a canon of doctrinal books;

- train clergy to preach the correct gospel teaching.

That is why he prepared a collection of church sermons called Postilla, which priests could use if they did not want to read their own.

The beginning of the Reformation and its goals

In the 16th century, Western and Central Europe was swept by a movement that was anti-feudal in its socio-economic essence and anti-religious in its ideological form.

The activists of this movement, called the Reformation, pursued the following goals: changing the relationship between church and state, restructuring the official church doctrine, and completely transforming the organization of the Catholic Church. The main focus of the reformation in Europe was Germany. What are Martin Luther's main ideas on this matter and how is it related to the Reformation movement? We will answer this question below.

Luther's reform activities

On October 18, 1517, Pope Leo X issued a bull on the remission of sins and the sale of indulgences in order to “Provide assistance in the construction of the Church of St. Peter and the salvation of the souls of the Christian world." This was precisely the beginning of Luther’s activities, which meant only the eradication of abuses within the Church. He opposed indulgences and had no plans to start a conflict with the Pope, and there was no talk of founding his own Church.

Theses against the Roman Church

Disillusioned with Catholic teachings, Luther wrote his 95 Theses, and on October 31, 1517, contrary to the legend that he nailed them to the church gates of Wittenberg, Martin sent them to the Bishop of Brandenburg and the Archbishop of Mainz. Thus began the confrontation between Martin Luther and the Pope.

The theses say that the state should not depend on the Church, and it should not act as a mediator between man and God. Despite the fact that there had been attempts to resist the Catholic Church before, Luther’s theses became popular and turned a simple monk into a revolutionary.

Pope Leo X made a lot of efforts to calm the rebellious man, declaring anathema to Martin, excommunicated him from the church, and even ensured that in April 1521 the reformer was condemned by the Reichstag of Worms. But this did not stop Luther, so the monk found himself outlawed.

Burning of a papal bull

The disputes raised by Luther began to pose a great danger to the Church, so the Pope decided to act more harshly, and in 1520 he issued a bull in which he excommunicated Luther as a heretic and condemned his writings.

In response, Luther publicly burned this bull in the courtyard of the University of Wittenberg and, in his address “To the Christian Nobility of the German Nation,” declared that the fight against papal dominance was the business of the entire German nation.

Issued on May 26, 1521, the Edict of Worms accuses Martin of heresy, but supporters of his ideas help their ideological mastermind escape by staging his kidnapping. In fact, Luther was settled in Wartburg Castle, where he began translating the Bible into German.

Bible Translation

The main thing for Luther remained faith in God, and he recognized only Holy Scripture as its source. That is why Luther decided to translate the Bible into German, and not its canonized version, the so-called Vulgate, but the original source.

The reformer worked on translating the Bible for about twelve years. For the first three months he worked on the text of the New Testament, relying on the translations of Erasmus of Rotterdam. Preparing a German translation of the Old Testament turned out to be a long and arduous task.

A book entitled "The Bible, which is the complete Holy Scripture in German" with the caption "March. Luther. Wittengberg" was published in 1534 and became the most published book in Germany.

The mental anguish that constantly accompanied Martin’s life haunted his translation work related to the Bible. Until his death, he constantly improved his creation, convening “revision commissions for the translation of the Holy Scriptures.” During his lifetime, several hundred errors were corrected in the translation.

Adoption of Protestantism

Protestantism as a religion received official acceptance by society in 1529 and was initially considered one of the movements of Catholicism, but a few years later a split occurred, dividing it into two movements: Lutheranism and Calvinism.

Jacques Calvin became the second major reformer who promoted the idea of the absolute predetermination of human destiny by God.

Causes of the Reformation

By the beginning of the 16th century, fragmented Germany was almost completely controlled by the Holy See. Unlike England, France and Spain, where the claims of the church were limited by strong royal power, here the popes and the highest German clergy freely and with impunity collected unprecedented amounts of taxes.

Rome, with its political and cultural flourishing, required huge financial investments, and the popes did not hesitate to maintain a court that European monarchs could envy. Germany was simply plundered, which caused natural indignation among its population. The sale of indulgences was widespread in the country, by purchasing which parishioners could receive forgiveness for any sins - it was just a matter of price.

Anxiety, dissatisfaction with the authorities and fear of the future determined the mood of the public. The anti-feudal movement grew in the villages, and uprisings against the greedy clergy arose in the cities. The humanism movement was gaining popularity in universities, criticizing the outward piety of Rome and its failure to comply with the principles of “Christian humanity”, close to the covenants of Christ.

Almost all demands for political and social change in Germany at the end of the 15th and beginning of the 16th centuries included church reforms, but the opposition was too heterogeneous. In 1517, Martin Luther (1483-1546), a graduate of the University of Erfurt, doctor of theology and monk of the Augustinian Order, was able to express public ideas and expectations.

Outraged by the sale of indulgences, Luther at the end of October 1517 sent his famous 95 theses to the Archbishop of Mainz and placed them on the doors of the parish church, which were further deepened and explained by himself and his followers.

Luther sought to eliminate the “damage” of the church by turning it to the ideals of Holy Scripture and rejected the Catholic dogma about the possibility of salvation of the soul only through the mediation of the clergy. He emphasized the importance of conscience, humility and personal repentance, without which sincere faith and the mercy of God were unattainable.

Preacher Books

Spreading the reformation spirit, Luther used the literary genres of pamphlets, ballads and woodcuts, which were unpopular at that time.

He published his 95 theses in printed form in the form of pamphlets and leaflets, realizing that this was one of the best and simplest ways to disseminate his own ideas. In many pamphlets, the author encouraged readers to discuss its contents and read it aloud to those who did not know how to read and write.

The Wittenberg priest also successfully used news ballads, made in the form of descriptions of events in poetic form, set to an already known melody. News ballads often combined a pious melody with secular or even blasphemous lyrics.

The main and most popular works of the reformer include the following:

- Berleburg Bible;

- Lectures on the Epistle to the Romans;

- 95 theses on indulgences;

- To the Christian nobility of the German nation;

- About the Babylonian captivity of the church;

- Letter to Mulpforth;

- Open letter to Pope Leo X;

- About the freedom of a Christian;

- Against the damned bull of the Antichrist;

- About the slavery of the will;

- About the war against the Turks;

- Large and Small Catechism;

- Letter of transfer;

- Praise for the music;

- About the Jews and their lies.