Olga Nikolaevna Romanova is the daughter of Nicholas II, the eldest child. Like all members of the imperial family, she was shot in the basement of a house in Yekaterinburg in the summer of 1918. The young princess lived a short but eventful life. She was the only one of Nikolai’s children who managed to attend a real ball and even planned to get married. During the war, she worked selflessly in hospitals, helping soldiers wounded at the front. Contemporaries remembered the girl with warmth, noting her kindness, modesty and friendliness. What is known about the life of the young princess? In this article we will tell you in detail about her biography. Photos of Olga Nikolaevna can also be seen below.

Birth of a girl

In November 1894, the wedding of the newly-crowned Emperor Nicholas took place with his bride Alice, who, after accepting Orthodoxy, became known as Alexandra. A year after the wedding, the queen gave birth to her first daughter, Olga Nikolaevna. Relatives later recalled that the birth was quite difficult. Princess Ksenia Nikolaevna, Nikolai's sister, wrote in her diaries that doctors were forced to pull the baby out of the mother with forceps. However, little Olga was born a healthy and strong child. Her parents, of course, hoped that a son would be born, a future heir. But they were not upset when their daughter was born.

Olga Nikolaevna Romanova was born on November 3, 1895, old style. Doctors performed the birth in the Alexander Palace, which is located in Tsarskoe Selo. And already on the 14th of the same month she was baptized. Her godparents were close relatives of the tsar: his mother, Empress Maria Feodorovna, and uncle, Vladimir Alexandrovich. Contemporaries noted that the newly made parents gave their daughter a completely traditional name, which was quite common in the Romanov family.

Happy childhood

Olga Nikolaevna was the middle daughter of Nicholas I and Alexandra Fedorovna. She recalled her childhood with warm feelings: family relationships were very friendly, parents raised their children in an atmosphere of trust and love. At the same time, the daughters were not pampered at all: the rooms of the eldest Maria, Olga herself and the younger Alexandra were devoid of luxury, the princesses bought books for the library with their own money, and even candles were issued according to the norm. Probably, Alexandra Fedorovna understood that her daughters would have to be married off to German princes, and from childhood she prepared them for their future family life.

The family paid special attention to the education of their daughters. Olga Nikolaevna was looked after by an English nanny, and her studies were supervised by the rector of St. Petersburg University, Professor Pyotr Aleksandrovich Pletnev and the poet Vasily Zhukovsky. She studied history and foreign languages, painted and sang well. True, the girl grew up rather closed, often feeling lonely, not finding support from her older and younger sisters. In her memoirs, she wrote that she even came up with a legend that she was not Nikolai’s own daughter, but had been replaced by a wet nurse. “My sisters were cheerful and cheerful, but I was serious and reserved. Compliant by nature, I tried to please everyone, and was often subjected to ridicule and attacks from Mary, unable to defend myself. I seemed stupid and simple-minded and cried into my pillow at night.”

early years

Princess Olga Nikolaevna was not long the only child in the family. Already in 1897, her younger sister, Tatyana, was born, with whom she was surprisingly friendly in childhood. Together with her, they made up the “senior couple,” as their parents jokingly called them. The sisters lived in the same room, played together, went through training and even wore the same clothes.

It is known that in childhood the princess had a rather hot temper, although she was a kind and capable child. She was often too stubborn and irritable. For entertainment, the girl loved to ride a double bicycle with her sister, pick mushrooms and berries, draw and play with dolls. In her surviving diaries there were references to her own cat, whose name was Vaska. Grand Duchess Olga Nikolaevna loved him very much. Contemporaries recalled that in appearance the girl was very similar to her father. She often argued with her parents; it was believed that she was the only one of the sisters who could argue with them.

In 1901, Olga Nikolaevna fell ill with typhoid fever, but was able to recover. Like the other sisters, the princess had her own nanny, who spoke exclusively Russian. She was specially taken from a peasant family so that the girl could better assimilate her native culture and religious customs. The sisters lived quite modestly; they were obviously not accustomed to luxury. For example, Olga Nikolaevna slept on a camp folding bed. Her mother, Empress Alexandra Feodorovna, was in charge of raising her. The girl saw her father much less often, since he was always absorbed in the affairs of governing the country.

Since 1903, when Olga was 8 years old, she began to appear in public more often with Nicholas II. S. Yu. Witte recalled that before the birth of his son Alexei in 1904, the tsar seriously considered making his eldest daughter his heir.

LiveInternetLiveInternet

Quote from TimOlya's message

Read in full In your quotation book or community!

Grand Duchess Olga Nikolaevna Romanova

Of all the Emperor’s daughters, only she was lucky enough to dance at adult, not “pink” balls* (* “Pink” or “children’s” were balls where girls aged 13-15 were present. - S. M.).

. Of all their friendly sisterly four with the intricately enchanting aroma of monogram - seal - signature: “OTMA”, only she managed to experience the gentle touch of the wings of First Love. But what did it bring her, this light, weightless touch? An acute, incomparable feeling of happiness, a captivating enchantment of a gesture, a look, which reflected the vague trembling of the heart, or the bitterness of pain and disappointment, so familiar to all of us from the first moment of the creation of the world, to us, the daughters of Eve and the heirs of Lilith?

Nobody knows anything for sure. The name of her Beloved has not yet been accurately established by any historian. Only guesses, fantasies, legends...

“The holy secret of the soul of a young girl” (*Phrase of Empress Alexandra Feodorovna from a letter to her husband, Emperor Nicholas II. - S.M.) remained with her forever. Her diaries almost did not survive - she burned them, almost all, during one of the searches in the terrible Yekaterinburg prison. The last of them, the dying one, seems extremely stingy, encrypted, faceless. But there is so much pain and desire to live in him, such a thirst for finding the forever lost golden thread of a calm, harmonious family world in which she grew up and which she lost... Then, in February 1917... And maybe much earlier, in the fall of 1905 - th...

What was she like, the eldest Tsesarevna, the beloved daughter of Emperor Nicholas II, the nurse of the Tsarskoye Selo hospital, the Russian princess from a bright fairy tale with a sad tragic end?

What an airy fairy she was in a gauze dress, with a pink ribbon in her hair, the same little girl for whom the midwife predicted a happy fate at birth, for the newborn’s head was thickly covered with light brown ringlets of curls.

To draw the strokes and zigzags of her Fate, you have to start with the worst.

Tsesarevna and Grand Duchess Olga Nikolaevna Romanova died in an instant, along with her parents, having received a bullet directly in the heart. Before her death, she managed to cross herself. She was not bayoneted alive like her other sisters. If this can be considered happiness, then yes, the eldest daughter of the last Sovereign of Russia was very lucky!

But let us turn to the beginning of such an “unusually happy journey” for the porphyry-bearing child. To his birth and infancy.

She was born on November 3 (15), 1895 in Tsarskoye Selo. She was a cheerful, active girl, the favorite of her father, who at first compared her “achievements” with the “achievements” of his sister Ksenia’s daughter, Irina. And he wrote in his diary, without hiding his pride: “Our Olga weighs a little more.” “At the christening, ours was calmer and didn’t scream as much when we dipped...”

One day, one of the adult guests asked jokingly, pulling her out from under the table, where she had crawled, trying to pull some object off the tablecloth: “Who are you?” “I am the Grand Duchess...” she answered with a sigh. - Well, what a princess you are, you couldn’t reach the table! - I don’t know myself. And you ask dad, he knows everything... He will tell you who I am. Olga answered seriously and hobbled on her still unsteady legs, towards the laughter and smiles of the guests.

When very tiny, all the princess girls were taught by their mother to hold a needle or embroidery hoop, knitting needles, and make tiny clothes for dolls. Alexandra Fedorovna believed that even little girls should be busy with something.

Olga loved to play with her sister Tatyana, born on May 28, 1897. Russian speech mixed with English and French, sweets, cookies and toys were shared equally... Toys were passed from older to younger. In the evenings, the girls quieted down around their mother, who read them fairy tales or quietly hummed English folk songs. The older girls were incredibly happy about their father, but even

We rarely saw him in the evenings, we knew he was busy...

Princesses Olga and Tatiana

When he had a free moment, he took both fair-haired babies on his lap and told them fairy tales, but not English ones, but Russian ones, long, a little scary, filled with magic and wonders...

Little mischievous girls were allowed to carefully stroke their lush, fluffy mustaches, which hid a soft, slightly sly smile.

Nicholas II, with daughters Olga and Tatiana

Nicholas II, Empress Alexandra Feodorovna, Princess Olga and Grand Duke Mikhail Alexandrovich

They grew up, and the viscous boredom of grammar, French, and English lessons began. Strict governesses monitored their posture, manners, movements, and ability to behave at the table.

Princesses Olga and Tatiana

Princesses Olga and Tatiana

However, everything was unobtrusive and simple, no excesses in food or delicacies. Lots of reading. And there wasn’t much time for pranks; soon Olga had younger sisters - Maria (born June 26, 1899, Peterhof) and Anastasia (born June 18, 1901, Peterhof). They all played together and learned while playing. The older ones looked after the younger ones.

Nicholas II, Empress Alexandra Feodorovna with daughters Olga, Tatiana, Maria, Anastasia, 1901

Grand Duchesses Olga, Tatiana, Maria, Anastasia

All four of us slept in the same room on folding camp beds. The young princesses even tried to dress the same. But the contents of everyone’s desks were different... favorite books, watercolors, herbariums, albums with photographs, icons. Each of them diligently kept a diary. At first these were expensive albums with gold embossing and clasps, on a moire lining, then - after the February storm and arrest - simple notebooks with pencil notes. Much was destroyed during searches in Tobolsk and Yekaterinburg.

Princess Olga

Princess Olga

The girls did a lot of sports: they played ball, rode bicycles, ran and swam well, were fond of the then newfangled tennis, horse riding, doused themselves with cold water in the mornings, and took warm baths in the evenings. Their day was always scheduled minute by minute by the strict Empress - their mother; they never knew idle boredom.

Princesses Olga, Tatiana, Maria and Anastasia

During their summer holidays in the Finnish skerries, Olga and Tatyana loved to look for small pieces of amber or beautiful stones, and in the meadows of Belovezhya and Spala (Poland) - mushrooms and berries. They appreciated every minute of relaxation that they could spend with their parents or in solitude - reading and journaling.

Olga in Finland

So, hand in hand with her inseparable beauty sister Tatyana and her younger sisters, whom she treated with maternal tenderness and severity, Olga Nikolaevna, the eldest child in a friendly and loving family, imperceptibly and captivatingly transformed from a plump, lively girl with a somewhat broad face into a charming teenage girl.

Yulia Alexandrovna Den, a friend of Empress Alexandra Feodorovna, recalled later, already in exile: “The eldest of the four beautiful sisters was Grand Duchess Olga Nikolaevna. It was a sweet creature. Anyone who saw her immediately fell in love. As a child she was ugly, but at the age of fifteen she immediately became prettier. Slightly above average height, fresh face, dark blue eyes, lush light brown hair, beautiful arms and legs. Olga Nikolaevna took life seriously and was endowed with intelligence and an easy-going character. In my opinion, she was a strong-willed person, but she had a sensitive, crystalline soul.” Devoted friend of the Royal family Anna

Taneyeva - Vyrubova, remembering the Tsar’s eldest daughter, seemed to complement Yulia Alexandrovna Den:

“Olga Nikolaevna was remarkably smart and capable, and teaching was a joke to her, why was she sometimes lazy. Her characteristic features were a strong will and incorruptible honesty and directness, in which she was like her mother. She had these wonderful qualities since childhood, but as a child Olga Nikolaevna was often stubborn, disobedient and very hot-tempered; subsequently she knew how to restrain herself. She had wonderful blond hair, big blue eyes and a marvelous complexion, a slightly upturned nose, like a sovereign.”

Who do all these beautiful portraits remind us of? Every now and then you catch yourself thinking that when approaching this charming image, you immediately remember the ideal of all girls - a kind and modest princess from a fairy tale

Fragile, gentle, sophisticated, not loving housekeeping... And the “purely Russian type” inherent, according to Taneyeva, to Olga Nikolaevna, does not interfere, but harmoniously complements this image. And the best place for a real Princess is at the ball... And Olga went there.

On the day of the tercentenary of the House of Romanov, her first adult appearance took place.

“That evening her face glowed with such joyful embarrassment, such youth and thirst for life that it was impossible to take your eyes off her. Brilliant officers were brought to her, she danced with everyone and femininely, slightly blushing, thanked her with a nod of her head at the end of the dance, S. Ya. Ofrosimova later recalled.

And here’s how Anna Taneyeva described the time of the maiden triumph of the eldest Tsesarevna:

“This autumn Olga Nikolaevna turned sixteen years old, the age of majority for Grand Duchesses. She received various diamond items and a necklace from her parents. All Grand Duchesses at the age of sixteen received pearl and diamond necklaces, but the Empress did not want the Ministry of the Court to spend so much money on buying them for the Grand Duchesses at once, and came up with the idea that twice a year, on birthdays and name days, they received one diamond and one pearl each. Thus, Grand Duchess Olga had two necklaces of thirty-two stones each, collected for her from her early childhood.

Olga, 16 years old

In the evening there was a ball, one of the most beautiful balls at the Court. They danced downstairs in the large dining room. The fragrant southern night looked in through the huge glass doors, wide open. All the Grand Dukes with their families, officers of the local garrison and acquaintances who lived in Yalta were invited. Grand Duchess Olga Nikolaevna, for the first time in a long dress of soft pink material, with blond hair, beautifully combed, cheerful and fresh, like a lily flower, was the center of everyone's attention.

Olga's birthday (16 years old), Livadia

She was appointed chief of the 3rd Elisavetgrad Hussar Regiment, which made her especially happy.

In the last years before the war, when the Grand Duchess turned eighteen, she could be spoken of as having an established young character, full of irresistible charm and beauty; Many who knew her in those years quite fully and strikingly consonantly outline the structure of her complex and at the same time clear inner world. P. Gilliard recalled with trepidation his students during these years:

“The Grand Duchesses were charming with their freshness and health. It would be difficult to find four sisters so different in character and at the same time so closely united by friendship. The latter did not interfere with their personal independence and, despite the difference in temperaments, united them with a living connection.”

But of all four, the devoted Monsieur Pierre Gilliard singled out the Grand Duchess Olga Nikolaevna, and later gave his best student the following description: “The eldest, Olga Nikolaevna, had a very lively mind. She had a lot of prudence and at the same time spontaneity. She had a very independent character and had a quick and funny resourcefulness in her answers... I remember, by the way, how in one of our first grammar lessons, when I was explaining to her conjugations and the use of auxiliary verbs, she suddenly interrupted me with the exclamation: “Oh, I understand, Auxiliary verbs are servants of verbs; only one unfortunate verb ‘to have’ must serve itself!”... At first it was not so easy for me with her, but after the first skirmishes the most sincere and cordial relations were established between us.”

Yes, all her contemporaries who knew her unanimously said that Olga had a great mind. But it seems that this mind was more philosophical than practical, everyday...

About her sister Tsesarevna Tatyana Nikolaevna, those close to the Romanov Family recalled that she was quicker to navigate various situations and make decisions. And in these cases, Olga Nikolaevna could willingly and freely give in to her beloved sister “the palm.” But she herself was not averse to abstractly and calmly reasoning, and all her judgments were distinguished by great depth.

Grand Duchesses Olga (1895-1918) and Tatiana (1897-1918)

She was passionately interested in history, her favorite heroine was always Catherine the Great. The Tsesarevna adored reading her handwritten memoirs, having unlimited access to a huge library in her father’s office. In response to the remarks of the Empress, the mother whom she respectfully idolized, that in the elegant memoirs of the Great Great-Great-Grandmother there were mainly only beautiful words and little action, Olga Nikolaevna immediately and vividly objected:

“Mom, but beautiful words support people like crutches. And it depends on people whether these words will turn into wonderful deeds. In the age of Catherine the Great there were many beautiful words, but also a lot of action... The development of Crimea, the war with Turkey, the construction of new cities, the successes of the Enlightenment.” The Empress involuntarily had to agree with her daughter’s clear and wise logic.

Grand Duchesses Olga and Tatiana, 1911

But more than other children, Grand Duchess Olga still looked like her Father, Emperor Nikolai Alexandrovich, whom she, according to teacher Sidney Gibbs, “loved more than anything in the world.” She adored him, her family called her “daddy’s daughter.” Dieterichs wrote: “Everyone around her was impressed that she had inherited more of her father’s traits, especially in her gentleness of character and simplicity of attitude towards people.”

Nicholas II with Olga and Tatiana

But, having inherited her father’s strong will, Olga did not have time to learn, like him, to restrain herself. “Her manners were “tough”,” we read from N.A. Sokolov. The eldest crown princess was quick-tempered, although easy-going. The father, with amazing kindness and no guile, knew how to hide his feelings, his daughter - a true woman - did not know how to do this at all. She lacked composure, and some unevenness of character distinguished her from her sisters. You could say that she was a little more capricious than her sisters. And Grand Duchess Olga’s relationship with her mother was a little more complicated than with her father. All the efforts of the mother and father were aimed at preserving the clear light of the “crystal soul” of their eldest child, perhaps the most difficult in character, and they completely succeeded.

Empress Alexandra Feodorovna with her daughter Olga

Here are excerpts from letters - examples of how the mother, the Empress, responded to some of the capriciousness and willfulness of her beloved eldest daughter:

“You are so sweet to me, be the same with your sisters. Show your loving heart." “First of all, remember that you must always be a good example to the younger ones... They are small, they do not understand everything so well and will always imitate the big ones. Therefore, you must think about everything you say and do.” “Be a good girl, my Olga, and help the four younger ones to be good too.”

Empress Alexandra Feodorovna with her daughters Olga, Tatiana Maria, Anastasia

The spiritual subtlety of Caesar's daughter did not allow her, over time and age, to perceive only the bright side of the world, and its shocks - the rebellion of 1905, the events in Moscow, extremely aggravated the impressionability of her nature. The rapid spiritual experience of the lovely Russian princess was also facilitated by the fact that, as a teenager, she experienced an acute feeling of falling in love, and could even endure some kind of great personal drama hidden from everyone.

Princesses Olga, Tatiana, Maria with Pavel Voronov

The correspondence of the Empress with her husband, the Sovereign, and Olga herself indicate something similar. In these letters we will find a concrete example of how carefully the August parents treated the feelings of their children: “Yes, N.P. is very sweet,” the Empress writes to her eldest daughter. - I don’t know if he is a believer. But there is no need to think about him. Otherwise, all sorts of stupid things come to mind and make someone blush.” “I know who you were thinking about in the carriage, don’t be so sad. Soon, with God's help, you will see him again. Don’t think too much about N.P. It upsets you.”

Grand Duchess Olga Nikolaevna and Pavel Voronov.

And further, in another letter: “I noticed for a long time that you were somehow sad, but I didn’t ask questions, because people don’t like being questioned... Of course, returning home to lessons (and this is inevitable) after a long holiday and a cheerful life with relatives and pleasant young people is not easy... I am well aware of your feelings for... the poor thing. Try not to think about him too much…. You see, others might notice the way you look at him and conversations will start... Now that you are a big girl, you should always be careful not to show your feelings. You cannot show your feelings to others when these others may consider them indecent. I know that he treats you like a little sister and he knows that you, little Grand Duchess, should not treat him differently.

Grand Duchess Olga Nikolaevna and Pavel Voronov.

Darling, I can’t write everything, it will take too much time, and I’m not alone: be brave, cheer up and don’t allow yourself to think about him so much. This will not bring any good, but will only bring you more sadness. If I were healthy, I would try to amuse you, make you laugh - then everything would be easier, but it’s not so, and nothing can be done. God help you. Don't be discouraged and don't think that you are doing something terrible. God bless you. I kiss you deeply. Your old mother."

Grand Duchesses Olga and Tatiana

“Dear child! Thanks for the note. Yes, dear, when you love someone, you experience his grief with him and rejoice when he is happy. You ask what to do. You need to pray with all your heart that God will give your friend strength and calmness to endure grief without complaining against God’s will. And we must try to help each other bear the cross sent by God. We must try to lighten the burden, provide assistance, and be cheerful. Well, sleep well and don’t fill your head with extraneous thoughts too much. It won't do any good. Sleep well and try to always be a good girl. God bless you. Tender kisses from your old mother."

Grand Duchess Olga

The Grand Duchesses had no secrets from Alexandra Feodorovna. They knew that she would carefully and carefully guard any of their secrets. And so it happened. Until now, not a single researcher, historian, or even just an inquisitive reader has been able to find out the name of Grand Duchess Olga Nikolaevna’s first love!

In January 1916, when Olga was already twenty years old, talk began about marrying her to Grand Duke Boris Vladimirovich. But the Empress was desperately against it. Grand Duke Boris was eighteen years older than the beautiful princess! The Empress wrote to her husband indignantly: “The thought of Boris is too unsympathetic, and I am sure that our daughter would never agree to marry him, and I would understand her perfectly…. The more I think about Boris,” the Empress writes to her husband a few days later, “the more I realize what a terrible company his wife will be drawn into…”

Grand Duchess Olga

Grand Duchess Olga

Grand Duke Boris Vladimirovich was very “famous” in the Romanov family for his countless love affairs and noisy revelries. Naturally, the hand of the eldest Grand Duchess would never have been given to a groom with such a reputation, and the Royal Family firmly made this clear to the old womanizer.

Grand Duke Kirill Vladimirovich and Grand Duke Boris Vladimirovich

Grand Duchess Maria Pavlovna, the mother of the unhappy pretender, “almost an empress” of the St. Petersburg elite, could not forgive her porphyry-bearing relatives for such an affront for the rest of her life! But the daughter’s peace of mind for loving parents was more valuable than the sidelong glances of relatives wounded in their ambitions and all sorts of secular gossip around...

Grand Duke Vladimir Alexandrovich, Grand Duchess Maria Pavlovna with children, (from left to right)

Andrey, Elena, Kirill, Boris 1899

In Olga’s head and heart there were completely different thoughts - “these are the holy secrets of a young girl, others should not know them, it would be terribly painful for Olga. She's so receptive! – the Empress wrote carefully to her husband, carefully protecting the inner world of her clear and at the same time complex soul.

Grand Duchess Olga

But like any mother, the Empress, of course, was worried about the future of her children. “I always ask myself who our girls will marry, and I can’t imagine what their fate will be,” she wrote bitterly to Nikolai Alexandrovich, perhaps clearly anticipating a great misfortune.

Empress Alexandra Feodorovna with her daughters Olga, Tatiana, Maria, Anastasia

From the correspondence between the Sovereign and the Empress, it is clear that Olga longed for great female happiness, which passed her by.

Her parents sympathized with her, but increasingly wondered: is there a couple worthy of their daughter? Alas... They couldn't name anyone. Even the Empress’s old, devoted valet A. Volkov, who loved the eldest Tsesarevna very much, grumpily remarked: “What a time has come! “It’s time to marry off my daughters, but there’s no one to marry, and the people are all empty, tiny!”

“The years seem distant to me,” recalls A. A. Taneyeva, “when the Grand Duchesses were growing up and we, those close to us, thought about their possible weddings. They didn’t want to go abroad, but there were no suitors at home. From childhood, the thought of marriage worried the Grand Duchesses, since for them marriage was associated with going abroad. Especially Grand Duchess Olga Nikolaevna did not want to hear about leaving her homeland. This issue was a sore point for her, and she was almost hostile towards foreign suitors.”

Grand Duchesses Tatiana, Maria and Olga with Anna Vyrubova on board the imperial yacht Standard

From the beginning of 1914, for poor Grand Duchess Olga, a straightforward and Russian soul, this issue became extremely acute; the Romanian Crown Prince (current King Carol II) arrived with his beautiful mother, Queen Maria; those close to him began to tease the Grand Duchess with the possibility of marriage, but she did not want to hear it.

Queen Mary and Crown Prince Carol II

“At the end of May,” recalls P. Gilliard, “a rumor spread at the Court about the upcoming betrothal of Grand Duchess Olga Nikolaevna to Prince Carol of Romania. She was then eighteen and a half years old.

Parents on both sides seemed to be well disposed to this proposal, which the political situation made desirable. I also knew that Foreign Minister Sazonov was making every effort to ensure that it came true, and that the final decision should be made during the upcoming trip of the Russian Imperial Family to Romania.

At the beginning of July, when we were alone one day with Grand Duchess Olga Nikolaevna, she suddenly said to me with her characteristic directness, imbued with the frankness and trust that our relationship, which began when she was a little girl, allowed: “Tell me really, do you know why we are going to Romania?”

I answered her with some embarrassment: “I think that this is an act of politeness that the Sovereign shows to the Romanian king in order to respond to his previous visit.”

Princess Olga at a French lesson under the guidance of tutor Pierre Gilliard.

“Yes, this may be the official reason, but the real reason?.. Ah, I understand, you are not supposed to know it, but I am sure that everyone around me is talking about it and that you know it.”

When I bowed my head in agreement, she added:

"So like this! If I don't want it, it won't happen. Dad promised me not to force me... but I don’t want to leave Russia.”

“But you will have the opportunity to return here whenever you please.”

- “Despite everything, I will be a stranger in my country, but I am Russian and I want to remain Russian!”

Grand Duchess Olga

On June 13, we sailed from Yalta on the imperial yacht “Standard”, and the next day in the morning we approached Constanta.

Visit of Nicholas II with his family to Romania

Solemn meeting; an intimate breakfast, tea, then a parade, followed by a sumptuous dinner in the evening. Olga Nikolaevna, sitting next to Prince Carol, answered his questions with usual friendliness. As for the rest of the Grand Duchesses, they could hardly hide the boredom that they always experienced in such cases, and constantly leaned in my direction, pointing their laughing eyes at their elder sister. The evening ended early, and an hour later the yacht departed, heading towards Odessa.

Romania 1914

The next morning I learned that the proposal for matchmaking had been abandoned, or at least postponed indefinitely. Olga Nikolaevna insisted on her own.”

This is how P. Gilliard ends this interesting memoir and adds in exile: “Who could have foreseen then that this wedding could have saved her from the grave fate that awaited her.”

Grand Duchess Olga

But who knows what fate would have prepared for the Russian Princess Olga Romanova if she lived on Romanian soil? During the occupation of Romania by Hitler, the sovereign royal family was forced to hide from the Nazis, and King Carol abdicated the throne! The steps of history for human destinies are always unpredictable, although they are repeated like frames of a film scrolled backwards...

Carol II of Romania

https://ricolor.org/history/mn/nv/family/olga/1/

https://romanovs.deviantart.com/gallery/

https://linnea-rose.deviantart.com

Series of messages “Nicholas II, his loved ones and his entourage”:

Part 1 - Empress Alexandra Feodorovna. Part 2 - Two different women in one. ... Part 22 - Love that destroyed the empire Part 23 - The life of Emperor Nicholas II in photographs Part 24 - Grand Duchess Olga Nikolaevna Romanova. Part 1. Part 25 - Grand Duchess Olga Nikolaevna. Part 2.

More about education

Olga Nikolaevna's family tried to instill in their daughter modesty and a dislike of luxury. Her training was very traditional. It is known that her first teacher was the reader of the Empress E. A. Schneider. It was noted that the princess loved to read more than the other sisters, and later became interested in writing poetry. Unfortunately, many of them were burned by the princess already in Yekaterinburg. She was a fairly capable child, so learning was easier for her than for other royal children. Because of this, the girl was quite often lazy, which often angered her teachers. Olga Nikolaevna loved to joke and had an excellent sense of humor.

Subsequently, a whole staff of teachers began to teach her, the eldest of whom was Russian language teacher P. V. Petrov. The princesses also studied French, English and German. However, at the last of them they never learned to speak. The sisters communicated with each other exclusively in Russian.

In addition, close friends of the royal family indicated that Princess Olga had a talent for music. In Petrograd she studied singing and knew how to play the piano. The teachers believed that the girl had perfect pitch. She could easily reproduce complex pieces of music without notes. The princess was also fond of playing tennis and drew well. It was believed that she was more predisposed to the arts than to the exact sciences.

Relationships with parents, sisters and brother

According to contemporaries, Princess Olga Nikolaevna Romanova was distinguished by her modesty, friendliness and sociability, although she was sometimes overly hot-tempered. However, this did not in any way affect her relationships with other family members, whom she loved endlessly. The princess was very friendly with her younger sister Tatyana, although they had almost opposite characters. Unlike Olga, her younger sister was stingy with emotions and more restrained, but she was diligent and loved to take responsibility for others. They were practically the same age, grew up together, lived in the same room and even studied. Princess Olga was also friendly with the other sisters, but due to the difference in age, they did not have such closeness as with Tatiana.

Olga Nikolaevna also maintained good relations with her younger brother. He loved her more than other girls. During quarrels with his parents, little Tsarevich Alexei often declared that he was now not their son, but Olga’s. Like other children of the royal family, their eldest daughter was attached to Grigory Rasputin.

The princess was close to her mother, but she developed the most trusting relationship with her father. If Tatiana in appearance and character resembled the empress in everything, then Olga was a copy of her father. When the girl grew up, he often consulted with her. Nicholas II valued his eldest daughter for her independent and deep thinking. It is known that in 1915 he even ordered Princess Olga to be woken up after receiving important news from the front. That evening they walked for a long time along the corridors, the king read telegrams aloud to her, listening to the advice that his daughter gave him.

Unsuccessful matchmaking

Maximilian of Bavaria was the first to become interested in Olga, but the princess did not like him. Then they decided to marry her to the Austrian Archduke Stefan. The young promising son of the Hungarian palatine Joseph fell in love with Alexander II, and besides, such a marriage could restore the family alliance with the House of Habsburg. But Olga failed to receive the Austrian crown - Vienna was not satisfied with the bride’s Orthodox origins. The princess also refused Stefan's cousin Albrecht - she did not feel much affection for him.

Olga was upset and decided that she could put off getting married. The father did not argue and assured his daughter that she was free to decide for herself who to marry. In the meantime, Grand Duchess Elena Pavlovna got down to business, and suggested that Olga pay attention to her brother Frederick of Württemberg. The age difference did not bother the Grand Duchess, but Olga was clearly upset. The prince was politely refused, after which the aunt seemed offended by her niece. In addition, Alexandra Feodorovna intended to marry Olga to Duke Adolf of Nassau, whom Elena Pavlovna had already chosen for her daughter Elizabeth. Adolf took Elizabeth as his wife, and his brother Moritz began to show signs of attention to Olga. But the princess changed her mind about marrying the handsome young duke - she believed that she must definitely follow her husband to his country, and Moritz was ready to stay in Russia.

Brilliant party

Olga's younger sister Alexandra died unexpectedly, and the princess went to Italy to accompany her mother for treatment. There she met the Crown Prince of Württemberg, Karl Friedrich Alexander. The young people had already met once, but then they were still teenagers. By the age of 22, Karl had transformed from a shy boy into a beautiful young man. The prince was so fascinated by the beauty and intelligence of the princess that a few days later he proposed to her. They got engaged in Palermo and got married in Peterhof in July. After two weeks of festivities, it was time to leave for Stuttgart. Olga wrote to Vasily Zhukovsky: “It is comforting in a moment of separation to think that the unforgettable grandmother (Empress Maria Feodorovna) was born in this land where I am destined to live and where Ekaterina Pavlovna left so many memories of herself. They love the Russian name there, and Württemberg is connected with us by many ties.”

Olga Nikolaevna, 1863. (wikimedia.org)

In Württemberg, Olga missed home, but did not sit idle. She was actively involved in charity work, took under the patronage of a pediatric clinic, founded the Nicholas Trustee Society and a school for girls, which later became known as the Royal Girls' Gymnasium. During the Franco-Prussian War, she established a society of voluntary nurses. The residents fell in love with the overseas princess for her kindness. Olga loved to organize balls and receptions, often hosted guests and relatives, and she herself came to Russia from time to time. Nicholas I died in 1855; the princess did not have time to attend his funeral. Five years later, she had to mourn her mother, who died surrounded by children. Since then, Olga has visited her homeland infrequently.

During the First World War

According to tradition, in 1909 the princess was appointed honorary commander of the hussar regiment, which now bore her name. She was often photographed in full dress and appeared at their parades, but that was where her duties ended. After Russia entered the First World War, the Empress and her daughters did not sit outside the walls of their palace. The tsar began to rarely visit his family at all, spending most of his time traveling. It is known that the mother and daughters cried all day when they learned about Russia's entry into the war.

Alexandra Fedorovna almost immediately introduced her children to work in military hospitals located in Petrograd. The eldest daughters underwent full training and became real sisters of mercy. They took part in difficult operations, looked after the military, and bandaged them. The younger ones, because of their age, only helped the wounded. Princess Olga also devoted a lot of time to social work. Like other sisters, she collected donations and donated her own savings for medicine.

In the photo, Princess Olga Nikolaevna Romanova, together with Tatiana, works as a nurse in a military hospital.

Possible marriage

Even before the start of the war, in November 1911, Olga Nikolaevna turned 16 years old. According to tradition, it was at this time that the Grand Duchesses came of age. In honor of this event, a magnificent ball was organized in Livadia. She was also given a lot of expensive jewelry, including diamonds and pearls. And her parents began to seriously think about the imminent marriage of their eldest daughter.

In fact, the biography of Olga Nikolaevna Romanova might not have been so tragic if she had nevertheless become the wife of one of the members of the royal houses of Europe. If the princess had left Russia in time, she would have been able to survive. But Olga herself considered herself Russian and dreamed of marrying a compatriot and staying at home.

Her wish could very well come true. In 1912, Grand Duke Dmitry Pavlovich, who was the grandson of Emperor Alexander II, asked for her hand in marriage. Judging by the memoirs of contemporaries, Olga Nikolaevna also sympathized with him. The engagement date was even officially set - June 6th. But it was soon torn apart at the insistence of the empress, who categorically did not like the young prince. Some contemporaries believed that it was because of this event that Dmitry Pavlovich subsequently took part in the murder of Rasputin.

Already during the war, Nicholas II considered the possible engagement of his eldest daughter to the heir to the Romanian throne, Prince Carol. However, the wedding never took place because Princess Olga categorically refused to leave Russia, and her father did not insist. In 1916, Grand Duke Boris Vladimirovich, another grandson of Alexander II, was proposed to the girl as a groom. But this time the empress rejected the offer.

It is known that Olga Nikolaevna was passionate about Lieutenant Pavel Voronov. Researchers believe that it was his name that she encrypted in her diaries. After she began working in the hospitals of Tsarskoe Selo, the princess sympathized with another military man - Dmitry Shakh-Bagov. She wrote about him quite often in her diaries, but their relationship did not develop.

Enviable bride

Olga Nikolaevna grew up to be a real beauty. They remembered that the tall, slender princess with a clear gaze and long eyelashes attracted the attention of anyone. “It is impossible to imagine a sweeter face on which meekness, kindness and condescension would be expressed to such a degree. With her graceful gait, with the ideal purity of her gaze, there was something truly unearthly about her.” Despite her apparent gentleness, Olga was sensible and proud.

Olga Nikolaevna. (wikipedia.org)

At the age of 18, Olga fell in love with Prince Alexander Baryatinsky, who himself had tender feelings for the princess. It was not possible to hide the affair - there were rumors that Alexander wanted to marry a young beauty. But the marriage for love was not destined to come true - the parents forbade it. And in order to help their daughter forget her first hobby, they decided to quickly marry her to an overseas prince. In addition, the eldest Maria had already been married to the Duke of Leuchtenberg, who was clearly lower in rank than her. So they wanted to find a more suitable candidate for the smart, beautiful Olga, one of the most enviable brides in Europe.

February Revolution

In February 1917, Princess Olga became very ill. First, she came down with an ear infection, and then, like the other sisters, she contracted measles from one of the soldiers. Subsequently, typhus was also added to it. The illnesses were quite severe, the princess lay delirious for a long time with a high fever, so she learned about the unrest in Petrograd and the revolution only after her father’s abdication of the throne.

Together with her parents, Olga Nikolaevna, who had already recovered from her illness, received the head of the Provisional Government, A.F. Kerensky, in one of the offices of the Tsarskoye Selo Palace. This meeting greatly shocked her, so soon the princess fell ill again, but from pneumonia. She was able to fully recover only towards the end of April.

House arrest in Tsarskoe Selo

After recovery and before leaving for Tobolsk, Olga Nikolaevna lived under arrest in Tsarskoe Selo with her parents, sisters and brother. Their regime was quite original. Members of the royal family got up early in the morning, then walked in the garden, and then worked for a long time in the vegetable garden they created. Time was also devoted to further education of younger children. Olga Nikolaevna taught English to her sisters and brother. In addition, due to measles, the girls' hair was falling out a lot, so it was decided to cut it off. But the sisters did not lose heart and covered their heads with special hats.

Over time, the Provisional Government increasingly cut their funding. Contemporaries wrote that in the spring there was not enough firewood in the palace, so it was cold in all the rooms. In August, a decision was made to transfer the royal family to Tobolsk. Kerensky recalled that he chose this city for security reasons. He did not imagine it possible for the Romanovs to move to the south or central part of Russia. In addition, he pointed out that in those years many of his associates demanded that the former tsar be shot, so he urgently needed to take his family away from Petrograd.

Interestingly, back in April, a plan was being considered for the Romanovs to leave for England via Murmansk. The Provisional Government did not oppose their departure, but it was decided to postpone it due to the serious illness of the princesses. But after their recovery, the English king, who was Nicholas II’s cousin, refused to accept them due to the deteriorating political situation in his own country.

Nicholas 2's sister Olga Alexandrovna.

On the advice of her sister, the Princess of Wales, and guided by the example of her mother-in-law, the girl’s mother decided to take an Englishwoman as a nanny. Soon Elizabeth Franklin arrived from England, bringing with her a whole suitcase stuffed with starched caps and aprons. “Throughout my entire childhood, Nana was a protector and adviser to me, and later a faithful friend. I can’t even imagine what I would do without her. It was she who helped me survive the chaos that reigned during the revolution.

She was an intelligent, brave, tactful woman; Although she performed the duties of my nanny, both my brothers and sister felt her influence.” - recalled the Grand Duchess.

Serov V.A. Portrait of Grand Duchess Olga Alexandrovna. 1893

Teachers and nannies followed the instructions of Alexander III: “I don’t need porcelain. I need normal, healthy Russian children.” In addition to the usual nuances of upbringing, Olga Alexandrovna also received a rather cool relationship with her mother. Empress Maria Feodorovna considered her daughter an ugly duckling with an intolerable character - the girl preferred to run around in games with her brothers rather than carry baby dolls in strollers

Unknown to her mother, she runs to the stables and spends hours fiddling with horses and other animals that were given to the grand dukes. She knew about her ugliness and did not consider it necessary to worry about it: caring for a tame white crow was much more interesting than shedding tears in front of mirrors. When a girl is given a camera, she becomes a real photographer, developing and printing the pictures herself. In addition, Olga Alexandrovna was a very capable artist.

Children's drawing by Olga Alexandrovna

The girl’s obvious talent had to be noticed and real artists began to be invited to her to teach the young artist the correct painting technique.

Olga and her father, nicknamed the “man-king” because of his preference for a simple life over royal regalia, in contrast to his still cool relationship with his mother, were connected by true love.

Olga et sa famille Livadia (1885)

When Olga was 12 years old, Alexander the Third suddenly died, and she grieved terribly for her beloved father, but still tried to support the young Tsar and His bride. Olga immediately fell in love with Princess Alix, indignant at the unfair attitude of her relatives towards her and always maintained that Sunny illuminated the life of the Tsar with sunlight.

Olga Alexandrovna and Alexandra Fedorovna were also brought together by their dislike for noisy entertainment and social life. As soon as the ball season began, Olga was already looking forward to its end.

Grand Duchess Olga with her brother, Grand Duke Mikhail Alexandrovich

Time did not affect Olga Alexandrovna’s external characteristics; according to her mother, she remained unattractive, so she was chosen as her wife by a man with whom it was necessary to connect the imperial house with a profitable dynastic marriage

With her first husband, Peter of Oldenburg

Prince Peter of Oldenburg was the strangest choice for Olga Alexandrovna's husband - he was 14 years older than her, was a distant relative of hers, was a gambler, was not distinguished by either intelligence or sophistication, and, finally, was a big drinker. Women were not interested in him at all - and throughout the fifteen years of this marriage, the prince never visited his wife in the bedroom. This couple's first wedding night was spent separately - the prince drank all night with friends and lost at cards.

Grand Duchess Olga Alexandrovna with her first husband Duke Peter Alexandrovich of Oldenburg

Olga Alexandrovna then gave all her unspent feelings and tenderness to other people’s children - she loved her nephew and nieces, the children of Nicholas II, and the children of other members of the imperial family. Tsesarevna Anastasia was Olga Alexandrovna's goddaughter, and the Grand Duchess loved her goddaughter more than anyone else for her character, which was so similar to her own.

Only art and communication with her family’s children helped her fight loneliness. Yes, pets – of which she always had a lot. So the Grand Duchess lived until 1903 - which changed everything in her life.

Stember V.K. Grand Duchess Olga Romanova.1908.

All the great princes, even girls, bore some kind of military title and were honorary members of various regiments of different branches of the military. Olga Alexandrovna bore the title of Honorary Commander of the 12th Akhtyrsky Hussar Regiment and, according to protocol, was required to participate in parades and reviews.

At one of the shows she met Nikolai Kulikovsky, colonel of the Guards cuirassiers, this meeting finally brought her happiness. She petitioned her brother Nicholas II to annul the marriage. The Tsar refused and insisted that Colonel Kulikovsky be included in the retinue of the Prince of Oldenburg. Olga, Prince of Oldenburg and Nikolai Kulikovsky were to live in the same palace for many years

Grand Duchess Olga Alexandrovna and Nikolai Kulikovsky

In 1914, Colonel Kulikovsky was supposed to command the Akhtur hussars in Rovno and Olga Alexandrovna went to the front behind him, with her own money she equipped a hospital and cared for the wounded as a sister of mercy.

The women of the Romanov dynasty had amazing abilities as sisters of mercy - kindness, lack of disgust, mercy and patience. Olga Alexandrovna was called when it was necessary to do the most painful and dirty dressings, to cheer up the soldiers, or even simply to clean up their uncleanliness.

Olga Alexandrovna in the center

In 1916, the emperor came to inspect the hospital. Outwardly, the last meeting between brother and sister was tense - but Nicholas II handed his sister his photograph with an English inscription on the back and a piece of paper with English text. During the program, no one was able to read what was written there. But this was the order of the emperor, dissolving the marriage of Olga Alexandrovna and Peter of Oldenburg. Almost the next day Olga Alexandrovna and her Colonel Kulikovsky got married

Wedding

In 1915, Olga Alexandrovna visited Tsarskoe Selo for the last time, saw the Empress for the last time, and in November 1916 saw the Sovereign Emperor for the last time. After the October coup, all the Romanovs, except the Kulikovsky family, were arrested. The authorities did not consider Colonel Kulikovsky's wife a member of the Imperial House. “I would never have thought that it would be so profitable to be a mere mortal,” Olga Alexandrovna joked. In 1917, the Kulikovsky couple had a son, Tikhon.

In Crimea in a stroller Tikhon Nikolaevich Kulikovsky

V.book Olga Alexandrovna with Tikhon in the village of Novominskaya, 1919

The situation in Crimea, where Olga and her family lived at that time, was deteriorating. Soon the Black Sea Fleet came under the influence of the Bolsheviks, into whose hands fell the two largest cities in Crimea - Sevastopol and Yalta. The inhabitants of Ai-Todor learned first about one bloody massacre, then about another. Ultimately, the Sevastopol Council forced the Provisional Government to issue it a warrant that would allow its representatives to enter Ai-Todor and investigate the “counter-revolutionary activities” of those living there.

One day at four o'clock in the morning the Grand Duchess and her husband were awakened by two sailors who entered their room. Both were ordered not to make noise. The room was searched. Then one sailor left and the other sat down on the sofa. Soon he got tired of guarding two harmless people and told them that his superiors suspected that German spies were hiding in Ai-Todor. “And we are looking for firearms and secret telegraph,” he added.

A few hours later, the two youngest sons of Grand Duke Alexander Mikhailovich snuck into the room and said that Empress Maria Feodorovna’s room was full of sailors, and she was scolding them in vain. “Knowing Mom’s character, I was afraid that the worst might happen,” said the Grand Duchess, “and, not paying attention to our guard, I rushed to her room.” Olga found her mother in bed, and her room in terrible disorder. Anger sparkled in her eyes. When leaving, the Bolsheviks took with them all the family photographs, letters and the family Bible, which Maria Feodorovna treasured so much.

Soon, alarming rumors began to arrive about the fate of the Royal Family, Alapaevsk prisoners and Grand Duke Mikhail Alexandrovich. One February morning in 1920, Olga Alexandrovna, along with her household, finally boarded a merchant ship that was supposed to take her away from Russia to a safer place. Although the ship was filled with refugees, they, along with other passengers, occupied a cramped cabin. “I couldn’t believe that I was leaving my homeland forever. I was sure that I would return again,” Olga Alexandrovna recalled. “I had a feeling that my flight was a cowardly act, although I came to this decision for the sake of my young children. And yet I was constantly tormented by shame.

Grand Duchess Olga Alexandrovna with her husband Nikolai Kulikovsky and children Tikhon and Gury

After emigrating, Olga Alexandrovna began to live in Denmark with her husband and children. She was convinced that the entire Royal Family had died, but despite the entreaties of her mother and husband, she rushed to Berlin to see the impostor Anna Anderson. “I left Denmark with some hope. I left Berlin, having lost all hope.” - the Grand Duchess recalled this.

Grand Duchess Olga Alexandrovna with her mother Dowager Empress Maria Feodorovna

She forced herself to come to terms with the terrible thought that the entire Family had died. Her old box contained small gifts from Anastasia Nikolaevna: a silver pencil on a thin chain, a tiny bottle of perfume, a brooch for a hat.

But the sister of the last Russian monarch, apparently, was not destined to peacefully meet the end of her life. Thunderstorms swept over Europe in 1939, and by the end of 1940 the Nazis had captured all of Denmark. At first everything was relatively calm, but then King Christian X was interned for his stubborn refusal to cooperate with the invaders. The Danish army was disbanded, and Olga Alexandrovna's sons spent several months in prison. — Then a Luftwaffe base was created in Ballerup. Having learned that I was the sister of the Russian Tsar, German officers came to pay their respects. I had no other choice, and I accepted them,” said Olga Alexandrovna.

The Kulikovsky family at breakfast on the veranda of their house in Ballerup. From left to right: Agnet (Tikhon’s first wife), Grand Duchess Olga Alexandrovna, Gury Nikolaevich, Leonid Guryevich, Ruth (Gury’s first wife), Ksenia Guryevna, Nikolai Alexandrovich Kulikovsky

To top it all off, Stalin’s troops approached almost the borders of Denmark. The communists repeatedly demanded that the Danish authorities hand over the Grand Duchess, accusing her of helping her fellow countrymen take refuge in the West, and the Danish government at that time would hardly have been able to resist the Kremlin’s demands. The accusation was not entirely unfounded, although in the eyes of other people there was no crime in the actions of the Grand Duchess.

Grand Duchess Olga Alexandrovna

After Hitler's defeat, many Russians who fought on his side came to Kundsminne, hoping to gain asylum. Olga Alexandrovna could not provide real help to all of them, although in a conversation with me she admitted that one of these people had been hiding in her attic for several weeks. But these emigrants truly fell from the frying pan into the fire, and those of them who arrived from the allied countries were aware that not every door would open for them in Europe. A threat loomed over the life of the Grand Duchess and her loved ones.

The Russian demands were increasingly insistent. The atmosphere in Ballerup became increasingly tense, and it became obvious that the days of Olga Alexandrovna’s family in Denmark were numbered. The Grand Duchess, who was sixty-six years old, did not find it very easy to leave her settled place. After much thought and family conferences, they decided to emigrate to Canada. The Danish government understood that the Kulikovsky family must leave the country as quickly and quietly as possible. There was a real danger of the Grand Duchess being kidnapped

At 66 years old, the Grand Duchess again radically changes her life, moves to Canada and settles on a farm near Toronto. Her neighbors called her “Olga,” and a neighbor’s child once asked if it was true that she was a princess, to which Olga Alexandrovna replied: “Well, of course, I’m not a princess. I am the Russian Grand Duchess." Olga Alexandrovna invariably received letters from all over the world, and even from Russia. An old Cossack officer, who had served 10 years in prison, whose next letter could end in a new sentence, continued to send them, because “all I have left in life is to write to you.”

Self-portrait of Grand Duchess Olga Alexandrovna

The Grand Duchess was not afraid of hard work, but she invariably lost in battles with the kitchen - she prepared the most simple dishes. Fortunately, neither she nor her husband were gluttons. She painted beautifully while still living in Russia, but her best works were created outside of Russia. However, painting in Olga Alexandrovna’s life is a separate issue.

In 1958, Nikolai Alexandrovich became seriously ill and died. Olga Alexandrovna survived him by only 2 years. She died on November 24, 1960.

Grand Duchess Olga Alexandrovna, photo 1955

Moving to Tobolsk

In August 1917, Grand Duchess Olga Nikolaevna and her family arrived in Tobolsk. Initially they were supposed to be accommodated in the governor's house, but it was not prepared for their arrival. Therefore, the Romanovs had to live on the ship “Rus” for another week. The royal family liked Tobolsk itself, and they were partly even glad of a quiet life away from the rebellious capital. They were settled on the second floor of the house, but they were forbidden to go out into the city. But on weekends you could attend the local church, and also write letters to your family and friends. However, all correspondence was carefully read by the house security.

The former tsar and his family learned about the October Revolution late - the news came to them only in mid-November. From that moment on, their situation deteriorated significantly, and the Soldiers' Committee, which guarded the house, was quite hostile towards them. Upon arrival in Tobolsk, Princess Olga spent a lot of time with her father, walking with him and Tatyana Nikolaevna. In the evenings the girl played the piano. On the eve of 1918, the princess again fell seriously ill - this time with rubella. The girl recovered quickly, but over time she increasingly began to withdraw into herself. She spent more time reading and almost did not take part in the home performances that the other sisters staged.

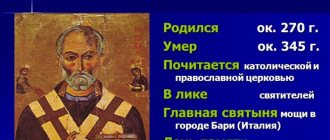

Holy Royal Passion-Bearer Olga, aka Grand Duchess Olga Nikolaevna Romanova (11/03/1895 - 07/17/1918) - the eldest daughter of the last Russian Emperor Nicholas II; died along with her family at the hands of atheists in the dungeons of the Ipatiev House. Heavenly patroness of women of her name. Memory - July 17, February 7 (in the Cathedral of New Martyrs and Confessors of the Russian Church), July 10 (in the Cathedral of St. Petersburg Saints), February 5 (in the Cathedral of Kostroma Saints), February 11 (in the Cathedral of Yekaterinburg Saints).

Today, faithful people, let us brightly honor the seven honorable royal passion-bearers, Christ’s one home Church: Nicholas and Alexandra, Alexy, Olga, Tatiana, Maria and Anastasia. For this reason, not being afraid of the bonds and sufferings of many kinds, I accepted death and desecration of bodies from those who fought against God and improved my boldness towards the Lord in prayer. For this reason, let us cry out to them with love: O holy passion-bearers, listen to the voice of repentance and the lamentation of our people, strengthen the Russian land in love for Orthodoxy, save from internecine warfare, ask God for peace and great mercy to our souls.

From the service of St. to the royal passion-bearers, troparion (tone 4)

The fate of Grand Duchess Olga Nikolaevna Romanova was initially quite successful. Happy childhood, love of learning, sincere affection for others. She was to become the wife of a monarch. However, history made its own adjustments, unfairly ruining her young life, but exalting her pure soul.

The first years of the Grand Duchess

Even today, looking at her face, it is impossible not to be touched. Eyes full of joy, thin line of lips. Delicate facial features and figures. But quite suddenly the realization comes - this girl was killed. Shot with particular zeal and for absolutely no reason!

St. was born Olga November 3 (15), 1895 in the imperial family of Nicholas II and Alexandra Feodorovna. The next day, the girl was baptized by Protopresbyter John (Yanyshev), and, at the end of the ceremony, the queen placed the red ribbon of the Order of St. on the little princess. Catherine.

Olga, her father's first-born and favorite, grew up cheerful and active. Nicholas II, without hiding his pride, shared his memories that Olga did not cry at the christening, behaved civilly, and at the same time remained very curious.

In the spring of 1897, Olga had her first sister. The royal couple was very fond of A.S.’s books. Pushkin, so it is no wonder that the second daughter, according to Onegin, was named Tatyana. According to recollections, the Grand Duchesses were inseparable; they played, read and drew together. Alexandra Fedorovna taught her daughters to do needlework from an early age. The sisters, having learned to confidently hold hoops and knitting needles, began making clothes for their favorite dolls themselves. The evening was usually spent with my mother reading fairy tales. Olga often wondered why her father was not around, but she soon realized that her father was at work.

Time has passed and the time has come for the young crown princesses to study. The list of their compulsory subjects included grammar, arithmetic, and foreign languages. Knowledge came easily to Olga. It was because of this, noted Pierre Gilliard, the girls’ teacher, that the Grand Duchess began to be a little lazy, which, however, did not harm her mastery of the material. But he especially remembered their first meeting. “Olga, a girl of ten years old, very blond, with eyes full of sly light, with a slightly raised nose, looked at me with an expression in which, it seemed, there was a desire from the first minute to find a weak spot, but this child exuded purity and truthfulness, which immediately attracted sympathy for him.”

Example for the younger ones

There is practically no time left for pranks. Olga and Tatyana, as older sisters, helped their parents raise their younger children: Maria (b. 1899) and Anastasia (b. 1901). Empress Alexandra insisted that Olga should set only a positive example. The eldest daughter sincerely fulfilled all her mother’s requests. Once Alexandra Fedorovna shared in a letter to her husband: “Olga was naughty, sitting on a small table, until she successfully broke it.” And the maid of honor Sophie Buxhoeveden recalled that the poor teachers had to experience many of Olga’s various jokes, which she specially invented. In general, the imperial children were always distinguished by their natural cheerfulness. They all played and studied together. The elders looked after the younger ones. All four of us slept in the same room on camp beds. Even the young crown princesses dressed the same. But the contents of everyone’s desks were different – favorite books, watercolors, herbariums, albums with photographs, icons. Each of the princesses diligently kept a diary.

Grand Duchesses (Olga - far left)

The governesses also taught the princesses manners, dancing and etiquette. Don't forget about sports. The girls swam well, played tennis and rode horses.

Father's outlet

Time passed, and from an ugly girl Olga turned into a charming, pretty girl with a fresh face, lush light brown hair and laughing blue eyes. In addition to her better appearance, another significant plus appeared for Olga Nikolaevna: she began to spend more time with her father. The Emperor took her to services and viewings. In 1909, he appointed the Grand Duchess chief of the third regiment of Elizavetgrad Hussars. It is possible that Nicholas II saw in his daughter some kind of outlet from the difficulties that befell him. After all, the Russian-Japanese War was going on.

Despite the fact that the crowned parents tried to create a quiet and calm environment for their children, the grand duchesses soon felt its severity.

In 1911, they witnessed an assassination attempt on Pyotr Stolypin, then prime minister of the empire. According to His Majesty’s recollections, the Tsar, Olga and Tatiana had barely left the theater box when they heard a loud, dull sound. Turning around, the family saw how the bloodied Stolypin slowly sank into a chair and tried to unbutton his jacket.

Sister of Mercy of royal blood

And in 1914, the First World War began. On the wave of rising patriotism, Empress Alexandra Feodorovna and her daughters Olga and Tatyana went to work as nurses in the hospitals of Tsarskoe Selo. By royal decree, warehouses of Her Imperial Majesty were opened in all palaces, which supplied the army with linen and dressings. The family's money was used to equip ambulance trains that transported the wounded to the areas of Moscow and Petrograd. The menu of the imperial table was reduced, because part of the food went to hospitals. The Empress declared that she would not sew either herself or her daughters a single new dress, except for her sister’s uniforms. Personal money of family members went to charity. Soon a committee of Her Imperial Highness Grand Duchess Olga Nikolaevna was opened to provide assistance to the families of soldiers. The king's eldest daughter was present at its meetings in person.

There was plenty of work in the infirmaries. Tatyana Nikolaevna emerged as a calm and efficient surgical nurse. Olga could not stand being present at operations for a long time, so she began to help other nurses in caring for the soldiers. According to eyewitnesses, the Grand Duchesses did everything the doctors ordered, including washing the feet of the wounded right at the station to prevent blood poisoning. Meeting new wounded at the station, brought directly from the front, the princess more than once had to accompany them and look after them. However, the princesses rarely gave themselves away, communicating on equal terms with ordinary Russian soldiers. After working at the hospital, Olga helped her younger sisters Maria and Anastasia sew and knit warm clothes for the active army.

“My home is Russia...”

In January 1916, when Olga was already 20 years old, talk began about marrying her to Grand Duke Boris Vladimirovich, but the Empress was categorically against it. She wrote indignantly: “The thought of Boris is too unsympathetic, and I am sure that our daughter would never agree to marry him. The more I think about Boris, the more I realize what a terrible company his wife will be drawn into...” Grand Duke Boris was eighteen years older than Olga and was “famous” in the Romanov family for his fleeting affairs and loud revelries. For the queen, her daughter’s peace of mind was more valuable than sidelong glances and secular gossip. Olga longed for female happiness, which, unfortunately, passed her by. Her parents sympathized with her, but wondered: is there a couple worthy of their daughter? Even the old valet of the Empress Volkov remarked: “What a time has come! It’s time to marry off my daughters, but there is no one to marry, and the people have become empty and “small.”

Of course, foreign candidates were also considered. For Olga, such a person was the heir to the Romanian throne, the future King Carol II. However, in a conversation with Pierre Gilliard, Olga made it clear that she was not going abroad. “If I don’t want it,” she told the teacher, “it won’t happen. Dad promised not to force me, but I don’t want to leave Russia. I will be a stranger in my country, but I am Russian and I want to be Russian! My home is Russia, and this is where I will stay.”

Tobolsk link

After the start of the February Revolution of 1917, Emperor Nicholas II signed a manifesto abdicating the throne. Olga reacted with understanding to her father’s action. However, in her heart she was very upset about this event, her health was greatly deteriorated, Olga began to get sick often. She was the first of her sisters to become infected with measles, which turned into typhus and occurred at a high temperature. It was also difficult to bear the fact that close people in an unpleasant moment completely turned their backs on the royal family. In August 1917, by decision of the Provisional Government, the emperor and his family were sent to Tobolsk, where they spent eight months.

The first time, about a month and a half, was perhaps the best in the imprisonment of the royal family; life, despite certain difficulties, flowed smoothly and calmly. “Preparing firewood for the kitchen and home,” recalled Pierre Gilliard, “was our main outdoor entertainment, and even the grand duchesses became addicted to this new sport. In the afternoon, another walk, if it’s not too cold. The rooms are very cold; in some only six degrees (the bedroom of the grand duchesses is a real glacier). We sat in thick knitted sweaters and put on felt boots. The main background of this life was melancholy, a bitter feeling of abandonment, and hence the desire to at least entertain oneself with something. They had set up a swing, but the soldiers carved completely inappropriate inscriptions on them with bayonets. They themselves built an ice mountain, which was great entertainment for the princesses, but a month later the soldiers destroyed it at night with pickaxes, as if on the grounds that, by climbing this mountain, the princesses found themselves outside the fence, in full view of the public. In the evenings the whole family gathered with their remaining loyal friends. Grand Duchess Olga played the piano, the Emperor read. Children often went to the guardhouse; they loved to talk with the guard soldiers and asked them about their families.”

Life in the Ipatiev House

It soon became known that due to the advance of the Czechoslovak Corps and the Siberian Army on the Eastern Front, Nicholas II, Alexandra Fedorovna and Maria Nikolaevna had to be transported to Yekaterinburg. The remaining children, due to poor health, were forced to stay in Tobolsk. The guards with the remaining prisoners were occupied by Latvians, led by fireman Khokhryakov and former gendarmerie detective Rodionov. The treatment of the Grand Duchesses became more outrageous. They were forbidden to close the bedroom door at night so that soldiers could enter and see what was happening in the room. The Grand Duchesses were not allowed not only to go out for a walk without permission, but also to go down to the lower floor.

In Tobolsk, Grand Duchess Olga Nikolaevna Romanova wrote a will on behalf of the emperor-father (probably she herself thought the same). It says: “The father asks you to tell all those who remained devoted to him, and those on whom they may have influence, so that they do not avenge him, since he has forgiven everyone and prays for everyone, and so that they do not avenge themselves, and remembered that the evil that is now in the world will be even stronger, but it is not evil that will defeat evil, but only Love...”

On May 20, 1918, the three Grand Duchesses and Tsarevich Alexei, accompanied by several members of their retinue, finally left Tobolsk. The convoy's abuse of them continued on the ship. Sentinels were posted at the open doors of the grand duchesses' cabins, so they could not even change clothes. All provisions sent by the residents of Tobolsk and the monastery were immediately taken away. Under heavy escort, the arrested were taken to a special train, which arrived in Yekaterinburg on the night of May 24. The remaining 53 days of life in Yekaterinburg became for Grand Duchess Olga days of physical deprivation, unbearable moral torture, bullying by guards, complete isolation from the world, doom and eternal anxiety. The royal family was housed in the top floor of the requisitioned mansion of the mining engineer Ipatiev. The Grand Duchesses occupied a room with one window overlooking Voznesensky Lane, next to the room of Their Majesties, the door of which had been removed. The first days there were no beds in their room; they slept directly on the floor, on straw mattresses. Olga rarely went for walks and spent most of her time next to her brother Alexei.

Family members were not allowed to engage in any physical labor. Food was brought from the Soviet canteen; later it was allowed to cook at home. Lunch was shared with the servants and Red Army soldiers. The soldiers entered the rooms occupied by the royal family whenever they wanted. There were always sentries inside and outside the room. When the princesses went to the restroom, the Red Army soldiers followed them, wrote various abominations everywhere, climbed onto the fence in front of the windows of the royal rooms and sang obscene songs. Small things were constantly stolen, and in the evenings the grand duchesses were forced to play the piano.

Brutal massacre

On July 4, 1918, the security of the royal family was transferred to a member of the board of the Ural Regional Cheka, Yakov Yurovsky. The Ural military commissar Fyodor Goloshchekin left for Moscow to resolve the issue of the future fate of the royal family. At its meeting on July 12, 1918, the Urals Council adopted a resolution on execution, as well as on methods for destroying corpses. On the night of July 16-17, 1918, the Romanovs did not go to bed for a long time. At half past one in the morning, Yurovsky woke up Doctor Botkin, ordering him to take the royal family to the basement. Seven family members descended from the second floor - Emperor Nicholas II, Empress Alexandra Feodorovna, their children Olga, Tatyana, Maria, Anastasia and Alexey, as well as physician Evgeny Botkin, chamberlain Alexey Trupp, maid Anna Demidova and cook Ivan Kharitonov . According to the memoirs of Ya.M. Yurovsky, the Romanovs were unaware of their fate until the last minute. When everyone was seated in the room, Yurovsky read out a resolution that the Council of Workers' Deputies had adopted a resolution on the execution, and the firing squad opened fire. Olga died under the first shots. Even the decorations sewn into the corset could not save her. However, Yurovsky said in his memoirs that after the first shots in the chest, all four girls remained alive. The firing squad finished them off with bayonets and shots to the head. After the execution, sheets from the princesses’ beds were brought into the room and the corpses were carried into them into a truck parked near the house. After this, the bodies were taken outside the city and dumped in an abandoned mine near the village of Koptyaki. After an unsuccessful attempt to collapse the pit, it was decided to bring the corpses to the surface and burn them. The bodies were buried in the first available place in a swamp near the road. While the new grave was being prepared, the security officers burned two corpses - the prince and the maid. They dug a hole at the burning site, stacked the bones, leveled them, lit a large fire again and covered all traces with ash. Before putting the rest of the bodies in the hole, they were doused with sulfuric acid, the hole was filled up, covered with sleepers and compacted. In this place, designated as Porosyonkov Log, those executed were finally buried.

Church on the Blood in Yekaterinburg on the site of the Ipatiev House

In July 1991, as a result of excavations, the remains of the royal family came to light. Numerous experts have confirmed this. On July 17, 1998, on the 80th anniversary of the execution of the royal family, the remains of members of the imperial family were buried in the Peter and Paul Cathedral in St. Petersburg.

Grand Duchess Olga Nikolaevna was canonized in the host of Passion-Bearers along with her family in 1981 by the Russian Orthodox Church Abroad, and in August 2000 by the Council of Bishops of the Russian Orthodox Church.

Link to Yekaterinburg

In April 1918, the Bolshevik government decided to move the royal family from Tobolsk to Yekaterinburg. First, the move was organized for the emperor and his wife, who were allowed to take only one daughter with them. At first, the parents chose Olga Nikolaevna, but she had not yet recovered from her illness and was weak, so the choice fell on her younger sister, Princess Maria.