Sukhumi and Abkhaz diocese

(formally within the Georgian Orthodox Church, in reality the status is not defined)

- Tel: +(995 44)-271971 (housekeeper of the monastery of St. Apostle Simon the Canaanite Hieronymus Andrey (Ampar)); fax: +(995 44)-260032 (diocesan administration)

- Cathedral city - Sukhum. Cathedral - Annunciation (Sukhum).

- Official site:

The Orthodox hierarchy in Abkhazia began in the first centuries of Christianity. It is known that the Bishop of Sevastopol, or Nikopsia, was present at the IV Ecumenical (Chalcedon) Council in 451. In 536, in ancient Nikopsia (Anacopia) or Pitsida, the episcopal see was revived, elevated in 541 to an archbishopric subordinate to the Patriarch of Constantinople. With the formation in the 8th century by Leon II of the Abkhazian kingdom, independent of the Eastern Roman Empire, which covered the entire territory of Western Georgia, the local Church gradually became independent. Around 840, the Nikopsian archbishops adopted the name of Bichvinta and Abkhazia, subsequently acquiring for themselves some rights of autocephaly. See the article Abkhaz Catholicosate for more details.

The Abkhaz-Imeretian Catholicosate, at different times being both dependent on Mtskheta and in an independent position, existed until the end of the 18th century, when the influence of the Russian Empire increased in the North Caucasus. The last Abkhaz Patriarch-Catholicos Maxim II remained in Russia in 1784 and died in 1795, after which the locum tenens of the Catholic see was Metropolitan Dosifei of Kutaisi, and in 1814 the Abkhaz Catholicosate was finally abolished. The church in Western Georgia came under the jurisdiction of the Georgian-Imereti Synodal Office and became part of the Georgian Exarchate of the Russian Orthodox Church.

On April 15, 1851, the Abkhaz diocese was restored as part of the Georgian Exarchate. Since 1869, the department was the Imereti Vicariate, and from June 12, 1885 it was renewed as an independent department under the name of Sukhumi.

After the collapse of the USSR and the subsequent Georgian-Abkhaz conflict, the Georgian bishop of the diocese, Metropolitan Daniel (Datuashvili), has been in Tbilisi since 1993. Since then, negotiations have been ongoing either on the entry of the diocese into the Russian Orthodox Church, or on the transition to the Ecumenical Patriarchate, or on the restoration of autocephaly of the Abkhaz Church. The Maikop bishop tonsured monks and ordained priests for the diocese. The Orthodox Church in Abkhazia is actually headed by priest Vissarion Aplia, chairman of the diocesan council.

Now limited to the borders of Abkhazia.

Bishops

- German (Gogolashvili) (September 8, 1851 - September 2, 1856)

- St. Alexander (Okropiridze) (September 2, 1856 - October 6, 1857, March 4, 1862 - May 30, 1869) for the first time - high school, archimandrite.

- Gerontiy (Papitashvili) (October 6, 1857 - November 16, 1859)

- St. Gabriel (Kikodze) (May 30, 1869 - 1886) v/u, bishop. Imereti

- Gennady (Pavlinsky) (December 28, 1886 - March 31, 1889)

- Alexander (Khovansky) (May 29, 1889 - February 12, 1891)

- Agafodor (Preobrazhensky) (March 2, 1891 - July 17, 1893)

- Peter (Drugov) (September 19, 1893 - January 17, 1895)

- Arseny (Izotov) (February 2, 1895 - March 26, 1905) [1]

- Sschmch. Seraphim (Chichagov) (April 10, 1905 - February 3, 1906) [2]

- Sschmch. Kirion (Sadzaglishvili) (February 3, 1906 - January 25, 1907)

- Dimitry (Sperovsky) (January 25, 1907 - July 25, 1911)

- Andrey (Prince Ukhtomsky) (July 25, 1911 - December 22, 1913)

- Sergius (Petrov) (December 22, 1913 - 1920)

As part of the Russian Orthodox Church

- Anthony (Romanovsky) (November 30, 1924 - 1927) senior, bishop. Yerevan

- Seraphim (Protopopov) (November 23, 1928 - April 3, 1930) high school bishop. Baku

As part of the Georgian Orthodox Church

- Spanish Ambrose (Helaya) (1918/1919 - 1921)

- John (Margishvili) (October 15, 1921 - April 7, 1925) [3]

- Christopher (Tsitskishvili) (April 7, 1925 - June 21, 1927) [4]

- Ephraim (Sidamonidze) (1927) v/u, ep. Tsilkansky

- Melchizedek (Pkhaladze) (1927 - 1928)

- Pavel (Japaridze) (1928)

- Varlaam (Makhaidze) (1929 - 1934)

- Melchizedek (Pkhaladze), 2nd time (1935 - 1943)

- Anthony (Gigineishvili) (1952 - November 24, 1956)

- Leonid (Zhvania) (1957 - 1964)

- Roman (Petriashvili) (1965 - 1967)

- Ilia (Gudushauri-Shiolashvili) (September 1, 1967 - December 23, 1977)

- Nikolai (Makharadze) (1978 - 1981)

- David (Chkadua) (1983 - October 1, 1992)

- Daniil (Datuashvili) (1992 - December 21, 2010) outside the diocese since 1993

- from December 21, 2010 - a diocese under the direct control of the Catholicos-Patriarch of All Georgia

Abkhazian split

Estimated reading time: less than a minute.

On June 27, 2012, clergy from the Council of the self-proclaimed “Holy Metropolis of Abkhazia”, Father Dorofey (Dbar) and Father Andrey (Ampar), announced a complete severance of their relations with the Russian Orthodox Church, tearing up the decrees of Bishop Tikhon of Maikop and Adygea imposing a ban on them in the priesthood for a period for three years for schismatic activities on the territory of Abkhazia. the Secretary of the Department for External Church Relations for Inter-Orthodox Relations of the Moscow Patriarchate of the Russian Orthodox Church, Archpriest , to comment on this event .

Fathers Dorotheus (Dbar) and Andrei (Ampar) proclaimed their independence a year ago, for which they were banned from the priesthood by Bishop Tikhon of Maykop and Adygea, since they are unemployed clergy of the Maykop diocese of the Russian Orthodox Church. So something fundamentally new did not happen.

According to the canonical norms of the Church, a clergyman of a particular diocese cannot so simply announce that he is leaving the subordination of his bishop - this means a schism. Therefore, the episcopal reprimand was completely justified. However, the Abkhaz fathers defiantly ignored this ban for a year, performing blasphemous services. Therefore, in May of this year, Bishop Tikhon extended the ban on them from serving for another three years. When Fr. They brought a decree to Dorotheus to extend the ban, he tore it up and announced that both he and Fr. Andrey (Ampar) does not obey anyone. Of course, such behavior is the basis for bringing these hieromonks to the church court, which, taking into account the gravity of the deed, may well end in a decision to deprive them of the priesthood. However, due to extreme economy and condescension, this was not done, taking into account the complexity of the church situation in Abkhazia after severe interethnic conflicts, the disorder of church life, the shortage of personnel, and the need of the Abkhaz people for spiritual enlightenment. Bishop Tikhon still calls these priests to correction, and the doors of repentance are not yet closed for them.

Reference:

As a result of the Georgian-Abkhaz war of 1992-1993, the clergy of the Georgian Orthodox Church, under whose jurisdiction Abkhazia is located, were forced to leave this territory, and the spiritual care of the flock has since been provided by the Russian Orthodox Church. In 2009, at a meeting of the clergy of Abkhazia, the manager of the former Sukhumi-Abkhaz diocese of the Georgian Church, Archpriest Vissarion Aplia, unilaterally proclaimed the autocephaly of the Abkhaz Local Church and appealed to the Patriarch of Moscow and All Rus' with a request to recognize the independence of the Abkhaz Church. Patriarch Kirill of Moscow and All Rus' noted in response to this appeal that the solution to church problems in Abkhazia is possible only on the basis of the canons and with the direct participation of the Georgian Church. In May 2011, in Abkhazia, participants in the Church-People's Assembly created another “metropolis” with a see in New Athos, the goal of which was proclaimed “an independent Abkhazian Church.” The meeting was convened by the Abkhaz clergy Father Dorofey (Dbar) and Father Andrey (Ampar). In turn, in 2011, Bishop Tikhon of Maykop and Adygea banned Father Dorotheus (Dbara) and Father Andrei (Ampara), who are unemployed clergy of the Maykop diocese of the Russian Orthodox Church, from serving for schismatic actions.

Photo: Anna Olshanskaya.

Operating churches of the Abkhaz Diocese

Sukhumi Cathedral of the Annunciation of the Blessed Virgin Mary.

The rector of the cathedral is priest Vissarion Apliaa. The clergy of the cathedral: Hieromonk Andrey (Ampar), Hieromonk Sylvestor, Deacon Gregory. Address: Sukhum, Abazinskaya str. 75. Tel..

Church of the Intercession of the Blessed Virgin Mary in Gagra.

The rector is Hieromonk Pavel (Kharchenko). Address: Gagra

Temple-chapel of the Pitsunda Saints in the village of Pitsunda.

The rector is Hieromonk Dorofei (Dbar). Address: Gagrinsky district, Pitsunda village. Tel..

Church of the Intercession of the Virgin Mary in Gudauta.

The rector is Hieromonk Basilisk (Leiba). Priests of the temple: Hierodeacon Savvaty (Lagutin). Address: Gudauta, Kharazia str. 26.

Church of the Assumption of the Virgin Mary in the village of Lykhny.

The rector is Archpriest Peter (Samsonov). The serving priest is Hieromonk Ignatius (Kiut). Address: Gudauta district, Lykhny village. Tel..

Church of the Intercession of the Virgin Mary in New Athos.

The rector is Hieromonk Dorotheos (Dbar). Address: Gudauta district, New Athos. Tel..

Temple of the Holy Apostle Simon the Canaanite in New Athos.

The serving priest is Hieromonk Dorotheos (Dbar). Address: Gudauta district, New Athos. Tel. +7 (840) 227-25-04.

Church of the Transfiguration of the Lord in the village of Yashtukha.

The rector is Hieromonk Gregory (Khorkin). Address: Sukhumi district, Yashtukha village.

Church of Saints Equal to the Apostles Constantine and Helen in the village of Akapa.

The rector is Hieromonk John (Svinukhov). Address: Sukhumi district, Akapa village. Tel..

Temple of the Prophet Elijah in the village of Agudzera.

Address: Gulripsha district, Agudzera village. Tel..

Drandsky Assumption Cathedral.

The rector is Hieromonk Dorofey (Dbar). Address: Gulripsha district, Dranda village. Tel..

Temple of the Archangel Gabriel in the village of Dranda.

Address: Gulripsha district, Dranda village.

Mokva Assumption Cathedral.

The clergyman is Priest Igor Artemyev. Address: Ochamchira district, village. Mokva. Tel..

Church of St. George the Victorious in the village of Yelyr.

The rector is Hieromonk Sergius (Jopua). Address: Ochamchira district, Yelyr village.

Church of St. George the Victorious in the village of Chuburkhinji.

The serving priest is Priest Nikita Adleyba. Address: Galli district, Chuburkhinji village.

Siege of Constantinople How the Russian, Georgian and Abkhaz churches quarreled: Lenta.ru report

Despite the fact that the Russian authorities recognized the independence of Abkhazia back in 2008, the status of the republic in the Orthodox world has still not been determined. Local clergy dream of separating from the Georgian Orthodox Church, but they will be able to do this only after the republic has its own bishop. President of Abkhazia Alexander Ankvab has already asked the leadership of the Russian Orthodox Church to determine the canonical status of the Abkhaz Church and put an end to the uncertainty, but the Russian Orthodox Church is in no hurry to make a decision. Meanwhile, an internal church split occurred in Abkhazia: several representatives of the clergy refused to wait for mercy from Patriarch Kirill - bypassing Moscow, they went to Istanbul, to the Ecumenical Patriarchate, for recognition.

The issue of separation of the Abkhaz Orthodox Church from the Georgian Patriarchate has been discussed almost since the end of the Georgian-Abkhaz war of 1992-1993. The first president of Abkhazia, Vladislav Ardzinba, turned to the late Patriarch of All Rus' Alexy II with a request to resolve the church issue. Father Vissarion Aplia, who now heads the non-canonical Abkhazian Orthodox Church, has also repeatedly asked the Russian Orthodox Church to ordain a local bishop, but has not yet received a positive response.

All local Orthodox churches continue to consider the territory of the republic to be part of the Georgian Orthodox Church (GOC), although Georgian bishops do not have real pastoral power over Abkhazia: in the early nineties, the Georgian clergy hastily left its territory and has not met with their Abkhaz “colleagues” since then.

In 2013, a split occurred in Abkhazia. Father Dorofey (Dbar) and Father Andrey (Ampar) - separatist monks from the New Athos Monastery - registered the self-proclaimed Holy Metropolis of Abkhazia. This displeased the official head of the non-canonical Abkhazian Church, Father Vissarion: he criticized the actions of independent clergy and accused the monks of disobedience.

The Russian Orthodox Church refrains from making harsh comments regarding the conflict between the Georgian Orthodox Church and the Abkhaz clergy. The position of the Russian Orthodox Church is this: church boundaries cannot be changed under any circumstances. But the actions of the New Athos monks, who announced their intention to create a metropolitanate back in 2011, caused an immediate reaction from Moscow: priests Dorotheos and Andrey were temporarily banned from serving, and in July 2013, the nearest Kuban Metropolis called on believers not to visit the New Athos Monastery and not to participate in rituals , which are carried out there by “forbidden” hieromonks.

The disgraced clergy ignored the criticism of Vissarion and the Russian Orthodox Church: in the summer of 2013, they turned to the Ecumenical Patriarchate in the hope that Patriarch Bartholomew I of Constantinople would finally determine the canonical status of the Republican Orthodox Church and ordain a bishop. And although both sides of the church conflict within the country advocate autocephaly, their methods are different.

Representatives of the leadership of the self-proclaimed Holy Metropolis of Abkhazia settled in the New Athos Monastery, the most famous religious complex on the territory of the republic. The recently renovated monastery is visited daily by hundreds of tourists and pilgrims during the peak summer season. Despite the call of the Kuban Metropolis not to visit New Athos, believers did not listen to the words of the Russian Orthodox Church, representatives of the monastery claim.

“Tourists, as everyone understands, are not interested in such statements of the Russian Church. As for the pilgrims, this also did not affect them in any way. Despite the prohibitions, even Russian clergy from different dioceses come and serve in our church. Although my classmate from Perm, shortly before he went to Abkhazia with his family on vacation, received an order under no circumstances to serve in the New Athos Monastery. In general, this is a matter of conscience, some serve, some don’t,” says German Marchand, secretary of the council of the self-proclaimed metropolis of Abkhazia. He reacts with a grin to the remark that in Russia he and other representatives of the metropolis are called “schismatics.” Marchand assures that the current inhabitants of the monastery only want to achieve self-government.

New Athos Monastery

Photo: Valery Matytsin / ITAR-TASS

The secretary of the metropolis is confident that it was the absence of a bishop in Abkhazia that led the clergy to a schism. Marchand considers the Russian Orthodox Church's proposal to resolve the issue untenable. The Russian clergy, according to him, proposes that Abkhazia exist under dual jurisdiction - the canonical territories will remain under the jurisdiction of the Georgian Orthodox Church, and administrative work will be handled by representatives of the Russian Orthodox Church.

“It is clear that the Russian Orthodox Church is trying to act as a diplomat in this situation, but we will never agree to such conditions,” Marchand explains. The decision to apply directly to the Ecumenical Patriarchate for the restoration of autocephaly was made when the clergy realized that Patriarch Kirill was not going to ordain a bishop - at least in the near future.

In order to convince the rest of the local churches that the Abkhazians needed to separate from Georgia, a survey was conducted on the territory of the republic and signatures were collected for the restoration of autocephaly. This was carried out by a special initiative group that was created in May 2013; it included deputies of the Abkhaz parliament and social activists. In the end, 70 thousand people took part in the survey, 97 percent of them signed for the independence of the Abkhaz church.

“Just so you understand, a little more than 100 thousand local residents have the right to vote in elections ( the entire population of Abkhazia is about 240 thousand people - note by Lenta.ru

). That is, almost the entire adult local population is in favor of the independence of the church. This suggests that the restoration of our church is the opinion and desire of the entire people. It is completely unacceptable for us to return to the fold of any other church,” concludes Marchant.

In May 2013, the President of Abkhazia, Alexander Ankvab, tried to help overcome the schism in the local church. Speaking about the religious crisis, he said that the authorities cannot afford to “distance themselves from discussing painful issues and not participate in the search for optimal solutions to resolve crisis situations.”

“With deep respect for the Ecumenical Patriarch, Constantinople is incomparably far from us in many units of measurement. Considering the impossibility of leaving believers without spiritual nourishment, remembering the historical connection between Abkhaz and Russian Orthodoxy, I believe that the Moscow Patriarchate can and should take on this high mission,” Ankvab said, essentially demanding that the leadership of the Russian Orthodox Church deal with what is happening in the republic. At the same time, he rejected the possibility of restoring church ties between Abkhazia and Georgia.

The interests of the Russian Orthodox Church in Abzakhia are now represented to the best of their ability by 66-year-old Father Vissarion. He was ordained a deacon by Georgian Patriarch Ilia II in the late eighties, and in 1990, two years before the Georgian-Abkhaz war, he was elevated to the priesthood. On September 15, 2009, he was elected by representatives of the Abkhaz clergy as temporary administrator of the self-proclaimed Abkhaz Orthodox Church. At the same time, Vissarion arrived in Moscow to read the funeral psalter over his comrade, crime boss Vyacheslav Ivankov (Yaponchik). Now the head of the Sukhumi-Pitsunda diocese, Father Vissarion, holds the post of rector of the Annunciation Cathedral in Sukhumi. He calls himself “acting bishop.”

Father Vissarion in the New Athos Monastery

Photo: Sergey Karpukhin / Reuters

“I thought that everyone in Moscow knew about this [conflict]. The Holy Patriarch of Russia issued a decree to all dioceses that it was forbidden to go to the Athos Monastery. What else can I add? - asks Father Vissarion, but immediately continues: - Andrei and Dorotheus committed the most heinous crime among priests - they rejected the canons and showed disobedience. There are many such situations. Which of us is not a sinner? But when a priest is banned because he violated canonical, dogmatic situations, this is the worst thing. Not only does he not have the right to give a blessing, he does not have the right to speak on behalf of the Orthodox Church.”

Father Vissarion emphasizes that the disgraced priests acted “bypassing him.” They are too ambitious for monks, the cleric is sure. “I perform the duties of a bishop in Abkhazia, but neither Dorotheus nor Andrey listened to me. They also did not listen to their bishop, who ordained them in Russia. They were not put on trial then, so as not to be deposed. The Church is being lenient. And who is Vissarion for them? He cannot judge them. They not only fell out of favor with me - they have a conflict with the Orthodox Church. But I am responsible before God for all this,” says the rector of the Annunciation Cathedral. He is sure that the clergy who settled in the New Athos Monastery are “confusing the people and bearing false witness.”

“The most blasphemous thing they did was create a metropolitanate. Whose metropolis is it? Neither Abkhazian nor Georgian, but whose? Metropolis of Bartholomew the Ecumenical? We will not allow anything to be given to Constantinople,” concludes Father Vissarion.

He never tires of emphasizing that the Abkhaz clergy is in excellent relations with the Russian Orthodox Church. “We now have a bishop - this is Moscow Patriarch Kirill. Is this not enough? He has an amazing love for our people, he is aware of our situation with Georgia, which we will definitely not go to,” says the clergyman. Father Vissarion is confident that “someday the time will come when someone will take upon himself the responsibility of becoming a bishop.” For this, the Abkhaz Church needs the support of the Russian Orthodox Church, and not the Ecumenical Patriarchate.

“We must begin our Orthodox restoration in Moscow. And it will happen, you just have to wait,” says the priest. The head of the Sukhumi-Pitsunda diocese is also outraged by the fact that the secular authorities, in his opinion, sided with the “schismatics”: “conducting surveys among the laity is from the political sphere, not from the church.” “They must give up their ambitions and become bishops. Stop saying that Vissarion is so bad and they are so good. It seems like I'm a bandit. I stopped being a bandit a long time ago ( Father Vissarion twice served a sentence for theft and robbery - note from Lenta.ru

), and when will they stop? — Vissarion reasons.

A woman who was present during the conversation with the cleric undertook to escort the correspondent to the exit from the cathedral. The clergyman introduced her as a press secretary, but she calls herself a novice. “Let me explain to you in a simple way what is happening here,” said the novice. - You understand, Vissarion raised Dorotheus and Andrei as his children, protected them from conscription in his time, and sent them to study. Now imagine this situation: a father forbids his child, say, to wear skinny jeans. And the child, as soon as his father leaves, changes the locks in the apartment and says that he now lives alone, according to his own laws, and dresses as he wants. That’s roughly what happened here too.”

According to her, even in their youth, Dorofey and Andrey seemed to her to be educated people, but cunning and sarcastic. “I also knew the secretary of this self-proclaimed metropolitanate, Herman Marchand, well. He is a smart man, but he has an ulcer, obviously. Of them, Andrey is the nicest. He even repented twice for what he and Dorotheus were doing without permission. But every time I fell under his influence again. They are probably connected by something material, very secret,” the woman shares her assumptions.

The appeal of banned Abkhaz clergy to the Ecumenical Patriarchate, bypassing their ruling bishop, cannot be considered a correct action from an ecclesiastical point of view, the Russian Orthodox Church believes. Archpriest Igor Yakimchuk, Secretary of the Department for External Church Relations for Inter-Orthodox Relations, does not deny that the church situation in Abkhazia needs to be normalized, but explains that “it is necessary to understand the conflict according to church concepts.”

“It is obvious that the use of ordinary standard solutions in a country that has experienced a war and has not yet fully healed its wounds is impossible. Now many in Abkhazia are guided by political or national emotions,” says the archpriest. At the same time, the republic is in a situation where it is impossible to escalate the situation, the clergyman believes. According to Yakimchuk, this is why the Russian Orthodox Church is lenient and does not defrock the monks from New Athos. However, their behavior can only lead to an aggravation of the situation, says a representative of the Russian Orthodox Church.

Secretary of the Department for External Church Relations for Inter-Orthodox Relations Archpriest Igor Yakimchuk

Photo: pravoslavie.ru

“Attempts in the current conditions to resolve the problem with a “cavalry attack” will only aggravate it,” Yakimchuk is sure. The Russian Orthodox Church, in turn, is making every effort to help the Abkhaz church, he claims.

“The Russian Church has been doing everything for many years to attract all interested parties to dialogue on the Abkhaz church problem, and will continue these efforts,” says Yakimchuk. He also recalls that for many years a total of several tens of millions of rubles were allocated from the Russian budget for the restoration of the New Athos Monastery.

“Therefore, at least, the situation looks very strange in which a monastery, originally built by Russia, decorated with the help of Russian craftsmen, restored with Russian money, is at the same time a stronghold of anti-Russian activities. How is this possible? We invariably address this question to the Abkhaz authorities,” says Archpriest Igor Yakimchuk.

In the Abkhazian self-proclaimed metropolis, on the contrary, they are confident that now the Russian church, led by Patriarch Kirill, is acting in the interests of Georgia. And all because the GOC represents the interests of Russian clergy in Ukraine.

The canonically unrecognized Orthodox Church of Ukraine has been trying to achieve independence since the beginning of the 20th century, but due to the tough position of the Russian Orthodox Church on this issue, it has been unable to establish a dialogue with Constantinople. Thus, disgraced clerics from New Athos believe that Abkhazia has once again become a bargaining chip in geopolitical wars.

Meanwhile, Patriarch of All Georgia Ilia II assures that between Russia and Georgia “love will last forever.” In January 2013, at the invitation of Patriarch Kirill, he visited Moscow and met with President Vladimir Putin. The meeting took place behind closed doors, but following its results, the cleric expressed confidence that Russia and Georgia will improve relations and again become “brotherly peoples.”

The secretary of the self-proclaimed Metropolitanate of Abkhazia, German Marchand, is irritated by the actions of the Georgian patriarch. “The Georgian church not only did not rise above this conflict, it showed what we call nationalism. When Georgians explained their escape [from Abkhazia during the war], they said that they left after their flock. Moreover, before the war, it must be understood that the flock of the GOC included not only Georgians, but also all other residents of Abkhazia,” explains German Marchand. According to him, in a political sense, the Abkhaz church is “the hook with which Georgia continues to hold Abkhazia.”

“This is a mutual responsibility: allow us to release the Abkhaz metropolis - we recognize Ukrainian autocephaly. Abkhazia has become a hostage to this situation. Somewhere very high above us, the issues of our own independence are being decided,” complains the secretary of the metropolis. “We urge our flock not to change their attitude towards Russian believers and clergy. Because patriarchs come and go, but people remain,” emphasizes the secretary of the council of the Holy Metropolis of Abkhazia.

The current situation, he says, is very similar to that immediately after the end of the war in 1993. “After the war, Boris Yeltsin and [then Georgian President] Eduard Shevardnadze agreed to close the borders and blockade Abkhazia. The calculation was that we would have nowhere to go and would return to Georgia. Before Putin came, we were in severe isolation. Even food did not reach here. Now the Russian Orthodox Church applies similar sanctions. Only under [Patriarch] Alexy was it so that the church behaved contrary to the state and supported the believers of the republic, but under the current leadership the scheme has changed - the church also came into conflict with the state, but now taking up arms against us,” says Marchand.

In the Orthodox world, for the resolution of conflicts like the Abkhazian one, it is customary to turn to the Ecumenical Patriarchate in Istanbul (Constantinople). Therefore, the decision on the autocephaly of the Abkhaz Church will have to be made by Ecumenical Patriarch Bartholomew I, who heads all Orthodox churches. The last decision on autocephaly was made regarding the Czechoslovak Orthodox Church in the early 2000s.

“The Ecumenical Patriarch does not have the same powers as the Pope, but by his equidistance, as first among equals, he plays the role of an arbitrator. We believe that he will not defend personal interests ten thousand kilometers away, since he simply does not have them,” notes Marchand.

The Ecumenical Patriarchate has not yet responded to the requests of the New Athos monks and has not voiced its position on changing church canonical boundaries. Meanwhile, in May 2013, Georgian Patriarch Ilia II traveled to Istanbul and spoke with the Ecumenical Patriarch. Following the meeting, the head of the GOC announced that the Ecumenical Patriarch “repeated several times that Constantinople recognizes the jurisdiction of the Georgian Orthodox Church in Abkhazia.”

According to the secretary of the self-proclaimed metropolitanate, German Marchand, formally all 144 churches, preserved to varying degrees on the territory of Abkhazia, belong to the state. He admits that the money spent on the restoration of the monastery was allocated under Moscow Mayor Yuri Luzhkov, including from the budget of the Russian capital. Funds were also provided by the Russian Federation, and later by the government of Abkhazia, says a representative of the monastery management.

“To be honest, I don’t know very well where exactly the funds for restoration are being sourced from. The state is doing this. The issue is personally supervised by the President. I know that every year a separate column for “restoration of churches” is included in the budget. This year, from 40 to 60 million rubles were allocated, I won’t give the exact amount,” says German Marchand. According to him, people became interested in the monastery at the very moment when the blockade of the republic ended. The clergy of Abkhazia does not deny the attractiveness of Athos for foreign churches.

“Whoever comes, representatives of any churches, everyone says: “Brothers, let’s be friends with you, you have a wonderful monastery, let’s take you into our jurisdiction.” I probably haven’t met the Old Believers yet,” says the secretary of the council of the Holy Metropolis of Abkhazia. In recent years, during patronal holidays, the monastery receives more than 500 pilgrims. “Most of the pilgrims, by the way, are from the Kuban Metropolitanate, where they call us ‘schismatics’,” Marchand boasts.

Restoration work in the monastery continues - the domes have already been changed, the facades have been painted, and the covering around the structure has been renewed. Now workers are restoring the Temple of Simon the Canaanite, located on the territory of the monastery. After the external cladding is completed, the monastery will begin restoring the frescoes - an expensive and lengthy procedure, which, according to representatives of the metropolis, will be financed by the government of Abkhazia.

Hieromonk Andrei Ampar became abbot of the New Athos Monastery in 1999, when the republic was still isolated from the rest of the world. Since then, his intentions to separate from the Georgian church have been repeatedly criticized by the Maykop diocese, where Father Andrei was ordained.

On May 26, 2011, he, like Father Dorofey, was banned from the priesthood for a period of three years. The formal reason was a church-people's meeting, at which the decision was made to create the Holy Metropolis of Abkhazia. The Russian Orthodox Church says that the abbot of the monastery never repented of his crime, and therefore the sentence was extended.

Hieromonk Andrey Ampar

Photo: personal Facebook page

The abbot of the monastery is outwardly quite calm about the conflict with the Russian Orthodox Church: the position of the Russian clergy is clear to him, and this already facilitates interaction between the churches. “Three years ago, the church issue was also not resolved; each representative of the Abkhaz clergy had a different vision of how the church should function in the republic. When the Holy Metropolis of Abkhazia was created, some certainty appeared, this helps us,” says the rector.

“We were waiting for what the Russian Orthodox Church is offering us now ten years ago. Now we want a little more, so the Russian Orthodox Church must keep pace with the growth of our church, which is growing stronger in the minds of believers,” notes Father Andrei.

In a conversation with me, he condemns the actions of the Russian Orthodox Church with restraint. But on his Facebook he publishes rather emotional entries: he calls what is happening in the republic “theater”, says that he is tired of deceit, and informs his readers that he is ready to leave the church.

“Clericalism has become unbearable, precisely as an “ism,” a complete rejection of these “sacred” castes and classes, with their long-bearded truths, with their stylized archaic dresses. With their vulgar confidence in the possession of the truth. It’s tragic when simplicity and naturalness degrades into some kind of theatrical show played out in “churches” and is imposed as something proper and necessary,” concludes the abbot of the New Athos Monastery.

From the history of Christianity in Abkhazia

The history of the date of conversion of the Abkhazians to Christianity has not yet been the subject of special research, although a number of works have touched upon some of its aspects.71 Meanwhile, the question of the time and conditions of the Christianization of Abkhazia, in our opinion, is important not only for the study of the history of Christianity and culture (in the broad sense of the word) of Abkhazia and the Caucasus as a whole, but also to study the history of early Byzantine diplomacy and the system of international relations of that period.

The Byzantine historian Procopius of Caesarea, the author of a historical chronicle concerning the history of the conversion of the Abazgians (the immediate ancestors of the Abkhaz people) to Christianity, wrote that the Abazgians were pagans, but during the reign of Emperor Justinian they accepted Christianity, that the emperor himself sent to them one of his eunuchs, originally Abkhaz, Euphrates, that at the same time the emperor erected a temple of the Mother of God for them, appointing priests to them, and ensured that they accepted the entire Christian way of life. Soon the Abazgs, who were striving for independence, overthrew their kings, which gave the opportunity to the Roman soldiers, who had long settled in those territories, to annex this country to the possessions of the Roman Empire.72

It is obvious that in this passage of Procopius’s work we are talking about an important political act: the conversion of the Abazgians to Christianity and the annexation of the country to the possession of the Roman Empire. In relation to the desire for independence and the overthrow of their Abkhaz kings, some researchers believe that the liberation of Abkhazia from Persia and its annexation to the Byzantine Empire took place here. One way or another, these events occurred almost simultaneously, during the reign of Justinian (527–565). In our opinion, this act was one of the manifestations of the characteristic foreign policy practice of the Byzantine Empire, the development of which undoubtedly belongs to Justinian himself.73

First of all, we note that, in our opinion, the goals of this sophisticated diplomacy, apparently, were to protect the borders of the empire in connection with the irreconcilable enemy - Persia and to maximize the expansion or preservation of areas of political hegemony, the creation of semi-independent federated states on its borders, whose loyalty in relation to the empire was strengthened mainly due to the adoption of Christianity.74 All these components of Justinian’s political doctrine received vitality and real embodiment during his foreign policy actions, especially during the period of complications in relations with an irreconcilable enemy - Sasanian Iran. It should be noted that the Caucasus region is of particular importance for the security of the empire, which was traditionally determined by elementary geopolitics, as well as by the fact that at the two extreme points of the isthmus separating the Black Sea from the Caspian Sea, the Greco-Roman civilization of the Mediterranean often met and collided with the expansion of Asian powers. The efforts of imperial diplomacy in this region were aimed both at achieving a favorable balance of power in the Caucasus and at creating a bulwark against the Persian attack through Asia Minor on Constantinople.75 The peoples of this region could provide real service to the empire in accordance with their geographical position and military resources. Thus, given by Dmitry Obolensky, in particular in the 6th century, on the eastern coast of the Black Sea, the Abazgs and Zikhs could provide the opportunity for the Byzantine fleet to operate off their coast and support the left flank of the northeastern front during the wars with the Persians. To the south, the Laz guarded the approaches to the northern coast of Asia Minor.76 The empire’s use of local military forces had occurred before. Sources name a separate military unit of Abkhazians (Abazgians), which was part of the Byzantine army and stood in Egypt in the 5th century. (It was called Ala prima Abasgorum, “The Best Abkhaz Wing”).77 At the same time, in Sevastopol (present-day Sukhum) there was a military unit of Romea: Prima cogors Claudia equitata, “The First Cavalry Cohort of Claudia.”78

Along with this, it is necessary to note the economic interest of the empire in the resources of the Eastern Black Sea region. Ship timber, wool, furs, leather, honey, wax, especially slaves - this is an incomplete list of goods exported by Byzantium from the region.79 From the 6th century, Iranian merchants monopolized the trade in Chinese silk. Byzantium, in turn, sought to bypass Iran and establish contacts, first of all, with Sogdian merchants - partners of Chinese silk suppliers. For this, a new route was chosen, which went from Central Asia through the North Caucasus, through the Abkhazian pass route, to the Black Sea, and then to Trebizond. From here the merchants traveled to Constantinople.80

An important reason for the increased military and diplomatic activity of Byzantium in Abkhazia in the 6th century. was the desire of Sasanian Iran to reach the shores of the Black Sea to conquer the imperial route to Constantinople.81 By the same time, Iran had abolished the kingdoms in the eastern part of Armenia, Albania and Kartli; the border of Byzantium and Persia at that time passed through the territory of modern Georgia, along the Likhi ridge, which separated Kartli and Lazika.82 Lazika and Abkhazia ended up in the territory subject to Byzantium.83 The Armenian highlands and Lazika, as well as Abkhazia, were then of particular strategic importance. It is no coincidence that during this period the Byzantines sent their troops to Lazika, where they built the Petra fortress.84 But, apparently, at that time the importance of the strategic position of Abkhazia was taken into account. Therefore, Byzantium, apparently, preferred diplomacy to war here.85

The fact is that the attitude of the empire towards the peoples of the periphery was of a very definite nature: maximum attention, formal loyalty, regular subsidies in exchange for the right of self-government, provision of government ranks and official positions to the leaders and heads of the peripheral peoples.86 At the same time, Byzantium primarily took into account its own imperial benefits, primarily in foreign policy terms. This explains, in our opinion, Justinian’s increased interest in the Abkhazians during that period. According to Byzantine historians, Justinian forbade the Abazg princes to castrate the children of their fellow tribesmen and sell them. He opened a school in Constantinople for Abkhaz children, restored the destroyed city of Sebastopolis (now Sukhum), recruited Abkhaz eunuchs in large numbers for official service in the capital, and recruited mainly Abazgs into his personal guard.87 On the initiative of Emperor Justinian himself, Christianity was declared official the state religion in Abkhazia, and the Church of the Virgin Mary was built for the newly converted Abazgs. And finally, bishops were sent from the capital to ordain the new Abkhaz clergy. These measures were carried out on behalf of the emperor himself by one of the capital officials, also an Abkhazian - Euphrates.88 This entire set of measures against Abkhazia and the Abkhazians on the part of Byzantium, in our opinion, cannot be explained otherwise than as a manifestation of the foreign policy course of the empire in western Transcaucasia - in a peculiar way expansion system without legionnaires. As a result of this, in our opinion, the Abkhazians were converted to Christianity.

However, it is hardly possible to explain the Christianization of the Abkhazians only as a result of Justinian’s strategic plans in the Caucasus. Already long before this period, the Abkhazians received attention from the ruling circles of Byzantium, as evidenced by the functioning of the above-mentioned military cavalry unit Ala prima Abasgorum and the presence of the Abazgians in such significant numbers at the court of the emperor.89 The conversion of the Abazgians to Christianity, of course, was due to a complex of factors, including of which, apparently, the main thing was the empire’s desire to consolidate its position in Western Transcaucasia as a counterbalance to Iran.

The ideological orientation of Byzantium's policy was based on the idea of the universality of the empire, which the Byzantines considered the only legitimate ruler of the civilized world, and the emperor was considered the supreme head of the Christian world and the representative of God on earth.90 In Abkhazia, as elsewhere, the ideological principle of pax Romana pax Christiana was implemented, then there are those who accepted the Orthodox faith “became civilized.”91 In addition to the chauvinistic and annexationist morality that guided the Byzantines, in this case it is necessary to note that, to some extent, the very situation of that period determined some integrative processes, for the then world, actually deprived internal unity, was united by Christianity against the common European enemy - the Saracens (in this case the Persians), and the Church with its feudal land ownership served as a real connection between different countries.92

The examples given here from the foreign policy life of the empire are, in our opinion, of exceptional importance in relation to the Christianization of Abkhazia, since the system of international relations of the Caucasus, Asia Minor and the Near East of that period largely determined the political and ideological situation in the Caucasus. In this regard, A.P. Novoseltsev rightly emphasizes that the history of Iran and Byzantium cannot be ignored when covering the history of the peoples of the Caucasus in the early Middle Ages.93

However, in our opinion, it should be noted that Abkhazia itself during this period, in terms of its economic and ethnic development, was apparently ready to accept a new faith - Christianity. Significant progress in the development of the material culture of the local population of that period is evidenced by numerous archaeological materials, discovered mainly in recent years. These are a variety of ceramic dishes, decorations of various types, weapons and horse equipment, numerous coins, tools, metalworking items and much more. A significant number of defensive, civil and religious structures of that period were also identified.94 These archaeological materials, architectural and artistic monuments reflect the high level of productive forces and production relations of the Abkhaz peoples, starting from the late antique period. They also testify to the region’s close ties with the vast cultural world of that era. The economic, socio-political and ethnic development, as well as the ideological state of the Abkhazians of the early Middle Ages, was largely determined by their diverse contacts with the developed peoples of the then civilized world, especially with the Persian and Greek world.95

The state of class relations in Abkhazia in the 6th century is characterized by a number of written sources.96 They testify, in particular, to the presence of real early feudal relations in the Abkhaz environment, which created favorable preconditions for the perception of the Christian religion.

In the literature on the history of Abkhazia there are still no works in which an attempt was made to determine the date of the baptism of the Abkhazians. Procopius of Caesarea, the author of the chronicle of the baptism of the Abkhazians, does not give the exact date of this event, although he dates it to the reign of Emperor Justinian. Judging by the historical situation of that time in the region of interest to us, we can assume that the official adoption of the new religion by the Abkhazians could have occurred in the late 20s of the 6th century. In our opinion, this particular time was the most tactically advantageous moment for carrying out such a peaceful act as the adoption of Christianity by the Abkhazians. In fact, this was the most peaceful period between the first (527) and second (540) wars between Byzantium and Sasanian Iran, when both states, regulating their internal affairs, were preparing for a new war against each other. At the same time, they did not miss the opportunity to attract peripheral countries and peoples to their side.

The fact is that after 540 the relationship between them changed dramatically. The “eternal peace” was violated; a huge Persian army led by Shah Khosrow invaded Syria in 541. After its devastation, the military theater was immediately transferred to Lazika, where Khosrow captured the fortress of Petra, built by Emperor Justinian. The Iranians did not stop within Lazika. And on the territory of Abkhazia they captured Sebastopolis and Cibilium.97 Thus, between 541 and 548. due to military operations in the Caucasus and in Abkhazia itself, Byzantium did not have the right moment to carry out mass baptism, build churches for worship, etc.98, so the baptism of the Abkhazians could have occurred between 527–541.99 More precisely, it could take place before 536, since we know from sources that by that time the Zikhs (Adygs) and Abkhazians had already professed Christianity, and the former even had a bishop.100 Perhaps this happened the next year after the Hunnic prince Grod or Gorda , who ruled in the Bosphorus, was baptized in 528.101

The most reliable seems to us to be the message of the Jerusalem Patriarch Dosifei that the Abazgians were converted to Christianity in 529.102 The fact is that, according to Procopius, as noted above, the Abazgians were converted to Christianity during the reign of Justinian. The latter, as is known, took the throne in 527. However, in the same year, a difficult, protracted war began between Byzantium and Persia,103 which, as we imagined, could interfere with the act of baptism of the people. However, it can be assumed that the official baptism of the Abkhazians took place in 529 or between 528–534. Apparently, at this time, Byzantium on the northern and northeastern coast of the Black Sea carried out on a large scale the Christianization of the peoples of the periphery, the future federates of the empire. Such activities of the empire could also occur through Chersonesus or the Bosporus. Chersonesos, as you know, was an important center of missionary activity of the Byzantine Church in Crimea. It was also used to monitor what was happening in the areas north of the Crimea and in the Caucasus region.

Naturally, the question cannot help but arise here: when was the Christian faith officially recognized by other Abkhaz ethnic formations of that period - Apsils, Missimians and others? How to interpret those numerous and interesting monuments of Christian architecture and objects of worship that have survived to this day, mainly discovered by archaeologists on the territory of Abkhazia, which date back to the 30s of the 6th century?

The literature has already expressed an opinion about the earlier Christianization of the Apsils and Missimians104, although there are no direct indications of this in historical sources. Procopius’ message that “the Apsilians have been Christians for a long time,” in our opinion, does not provide a complete basis for a categorical statement about the official Christianization of the Apsilians until the 30s of the 6th century. Firstly, it is unclear what period of time separates this moment from this statement of Procopius - “for a long time.” Secondly, the words often repeated by Procopius “from ancient times” or “from ancient times”, in all likelihood, do not carry a certain meaning for him. At least his message in the book “The History of the Wars of the Romans with the Persians” that the Abazgians “since ancient times” were friendly to Christians and the Romans105 clearly contradicts his message about the adoption of Christianity by the Abazgians in the 6th century, during the reign of Justinian. The message of another historian and chronicler, Agathius of Myrinea, that during negotiations with Roman military leaders, the Mysimian ambassadors called themselves representatives of a people who had been “since ancient times” subordinate to the Romans and the same religion106, in our opinion, also does not speak of the official adoption of Christianity Missimians. Naturally, here we are talking about the spread of Christianity in Abkhazia, apparently, primarily under the influence of the Pitiunt bishopric, which functioned here from the 4th century AD, which we have already written about.107 In addition, the Missimian ambassadors at that moment could have said so for diplomatic reasons, to express their commitment to the Romans.

However, one cannot ignore the fact that in Abkhazia, thanks to archaeological excavations, interesting architectural monuments for religious purposes were discovered, dating back to before the 6th century. We mean, first of all, the ancient basilica, in which Bishop Stratophilus, a participant in the First Ecumenical Council in Nicaea, served, and a three-nave basilica with mosaics (both from Pitiunt), churches No. 2, No. 3 in the mountainous Tsebelda and Sebastopolis (Sukhum)108 and others.

Recently, several works have been devoted to the early Christian monuments of Abkhazia, among which the articles by V.A. Lekvinadze, L.G. Khrushkova, M.K. Khotelashvili and A.Ya. Yakobson and others.109 None of these articles, including the work of L.G. Khrushkova, specially dedicated to Christianity among the Apsils,110 does not claim that the official conversion to Christianity of the Apsils or other early Abkhazian peoples took place before the 6th century.

From our point of view, the mentioned early Christian monuments appeared in Abkhazia as a result of the activities of the clergy, mainly of the Pitiunt diocese. Moreover, according to L.G. herself. Khrushkova, who studied the Tsebeldin churches, the latter are similar to the Pitiunt churches, which, in turn, have analogies with the early Christian monuments of Rome and Asia Minor.111 In this regard, it is not without interest to cite information from the Byzantine author of the 5th century AD - Theodoret of Cyrus, who regrets, that not all peoples who are loyal to the Romans, including the Abazgians, live according to Roman laws; although the Scythians, Sarmatians and almost all peoples and tribes accepted the laws of Christ, which did not require weapons.112 In a word, in our opinion, the functioning of the Pitiunt bishopric on the territory of Abkhazia in the 4th century can indicate the influence of Christianity on the Abkhazians. However, the official baptism of the Abkhazians occurred later - at the end of the 20s of the 6th century AD. Although late antique church sources, telling about the conversion to Christianity of representatives of some peoples of the Caucasian region, in particular the Abazgs, are of the opinion that they (the Abazgs) accepted Christianity even then, that is, before the 6th century. For example, the Acta Andrea says: “The great Andrew, together with Simon, arrived in the Alanian country and reached a city called Fusta; having performed many miracles and signs there, instructing and enlightening many, they headed to Abasgia; and having come to Sebastopol the Great, they proclaimed the word about faith and the knowledge of God; and many of those who listened were converted.”113

It was already noted above that Christianity penetrated into the Caucasian regions, in particular Abkhazia, earlier than it was recognized here as a state religion. For example, it is known that in 325 on the territory of Abkhazia, namely in Pitsunda, there already existed a strong Christian bishopric, the representative of which took part in the First Ecumenical Council.114 Naturally, Christianity could already penetrate into the environment of all Abkhaz ethnic formations - Abazgs, Apsils and so on. Therefore, it is not surprising that monuments of the Christian cult of the 4th and 5th centuries AD were distributed on the territory of Abkhazia.115

Many authors have written not only about the early introduction of Abkhazians to Christianity, but also about their adherence to Christian traditions. For example, some authors of the 19th century wrote that the “Abkhazians” living on the shores of the Black Sea still celebrate Easter for three days, the Day of the Descent of the Holy Spirit, and on December 25 they celebrate the Nativity of Christ.116 The antiquity of Christianity in Abkhazia is confirmed by such facts. In the recently republished major work “History of the Russian Church” by Metropolitan Macarius (Bulgakov), in the appendix entitled “Ecumenical Saints of the 1st–10th Centuries” the following holy men are listed as revered in Abkhazia: Holy Apostle Andrew the First-Called, Simon the Canaanite, Martyr Basilisk and St. John Chrysostom.117 In the same work, in the chapter “The Church of Christ in Georgia, Colchis and Abkhazia”, only Abkhaz archaeological discoveries - ancient Christian structures - are given to illustrate the early Christian monuments in this region (pp. 150–157). There is no doubt that the Abkhazians were introduced to Christianity very early and, apparently, Academician N.Ya. was right. Marr, when he wrote somewhat exaggeratedly that the Christianized part of the Abkhaz people carried the Greek enlightenment with the Eastern Christian culture.118

In a word, concluding this passage, regarding the date of baptism of the Abkhazians, we can note that they were introduced to Christianity from the earliest (apostolic) period, however, they, as it were, for the second time, already officially accepted Christianity as a state cult in the 6th century, just as it was in Caucasian Albania.119 The conversion of the Abkhaz to Christianity was apparently due not only to the military and clerical diplomacy of Byzantium during its war with the Persians, but also to the natural development of the religious consciousness of the Abkhaz people.

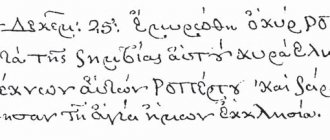

Certain circumstances force us to pay attention to another issue. We are talking about clarifying the nationality of the clergy and laity in the ancient bishopric of Pitiunta. It is known that ancient Pitiunt, like Dioscurias, was a Greek colony on the eastern coast of the Black Sea.120 Naturally, this city remained mainly Greek until the late antique period.121 Apparently, by the late antique period, Greek traditions in this city should were preserved not only in architecture, but also in ideology, art, and craft.122 In this regard, in all likelihood, the Christian diocese that functioned in Pitiunta was no exception. Researchers pointed out that the Pitiunt diocese was at that time one of those that was founded by the Greeks on the eastern coast of the Black Sea for the religious needs, primarily of Greek colonists.123 Moreover, as we know, in ecclesiastical terms this diocese then belonged to to the Pontus Polemontian metropolitan district.124 However, recently some scientists have been trying to prove that the culture of ancient Pitiunt was only local. As the main argument to prove this thesis, there were attempts to use the Greek inscription discovered on the Pitsunda mosaic. V.A. Lekvinadze, in a special article, convincingly proved that the inscription on the mosaic is a memorial one and is dedicated to one of the famous and revered martyrs of the early Middle Ages - Orentius and his brothers.125 Nevertheless, T.S. Kaukhchishvili is inclined to believe that this inscription is a ktitor’s and its full reading is as follows: “By the prayer of Aurélie and his entire house”126 - the author restores the Greek letter lambda, which, in her opinion, is missing from the lacuna, and wants to prove that this word must be read as “ Orel", that is, "Eagle", which is consonant with Georgian names like Bevreli, Nateli, etc.127 I am not an expert in the field of epigraphy and I do not undertake to challenge the reading of the text proposed by T.S. Kaukhchishvili. However, in my opinion, it is difficult to refute the opinion of V.A. Lekvinadze, since his arguments and arguments are in good agreement with the fact that the construction of the Pitiunt basilica with mosaics was due to its use as a martyrium.

It would hardly be worthwhile to dwell in detail on the reading of the inscription if it were not used as an argument to prove that in the 4th century in Lazika Christianity became the state religion.128 It is assumed that if the mosaic with the text is dedicated to the Georgian, therefore, the rest of the inhabitants of Pitiunta are also , also Georgians, or rather Laz, judging by the interpretation of the mosaic, adopted Christianity as the state religion in the 4th century. This, in turn, is used to prove the simultaneous adoption of Christianity in the 4th century throughout Georgia, both in its eastern part - Iberia, and in its western part - Lazika.129

Of course, Christianity in Western Georgia (Lazika) could have been declared the state religion at the same time as Iberia in the 4th century. However, the name of Orel alone (even if it was laid out on the mosaic) is completely insufficient to prove such a thesis, and even more so to conclude that ancient Pitiunt was a Georgian city. Lazika itself, as is known, was ethnically and geographically located in Western Georgia, without capturing Abkhazia, especially the historical Abazgia, on whose territory Pitiunt was located. In particular, according to S.K. Kaukhchishvidi, Pitiunt was at that time a significant and well-known center of Abazgia.130 The fact that the Western Georgian, or rather, Laz metropolitanate in the earlier Middle Ages did not include the territory of Abazgia along with its autocephalous archbishopric is evidenced by the Constantinople church narrative documents, the so-called Notitiae episcopatuum.131 Procopius of Caesarea also reports the conversion of the Abazgians (separate from the Lazians) to Christianity under Emperor Justinian. As for the ancient bishopric of Pitiunta, it was Greek: naturally, both the clergy and parishioners here were mainly Greek. The inscription on the mosaic, like the mosaic itself, in type, form and content refers to typical monuments of the Greco-Roman world and is executed in its traditions.132 And if some layers of the local population were attached to this bishopric, then, in our opinion, these had to be, first of all, the Abazgs, for Pitiunt was located on their territory.133 As for the statement of representatives of the Georgian clergy, in particular, Bishop Kirion, that, supposedly, “Georgia enlightened the Abkhazians with Christianity and therefore has the right to govern them "134 it has no logical and historical basis.

The important question about the location of Justinian’s construction of the Church of the Virgin Mary for the Abkhazian neophytes has not yet found a final solution. The debate on this issue has been going on for about a hundred years. Frederic Dubois de Montperay, N. Kondakov, P.S. expressed their opinions on this issue. Uvarova, Y. Kulakovsky, K. Kekelidze, L. Melikset-Bekov, S. Kaukhchishvili, G. Chubinashvili, Z. Anchabadze, V. Lekvinadze.135 It is obvious that complex historical and archaeological research is needed to solve this important issue. Let us only note that Yu. Kulakovsky’s point of view about the location of this temple in Sebastopolis seems to us the most probable. Yu. Kulakovsky’s conclusions, in particular, are based on data from early medieval church sources (Notitiae episcopatuum), according to which the residence of the archbishop from the 7th century could have been located in the place where a special church was originally built for the baptism of the Abazgs.136 This conclusion is justified by the fact that, according to article by Professor L.G. Khrushkova - “The New Octagonal Church in Sebastopolis in Abkhazia and its liturgical structure” - in ancient Sebastopolis (present-day Sukhum), the foundation of an ancient church and the text of a Greek inscription were discovered (she herself co-authored the excavation),137 which prove that even in the 5th century there existed bishopric.

The question of the language in which the new teaching was preached in Abkhazia is also important. There is no doubt that oral preaching among neophytes, including Abkhazians, was initially conducted in the language of the local Abkhazian population, otherwise no sermon would have made sense. The sermon from the official church pulpit was conducted in Greek. However, it is known that, in contrast to the Catholic Church, the Byzantine Church facilitated the activities of its missionaries by allowing them to even conduct services in local languages.138 It can be assumed that here, at first, Hellenized Abkhazians who spoke their native and Greek languages could be used to preach the new teaching , who received their initial church education at the Constantinople school, apparently specially opened for the Abkhaz clergy.139 In all likelihood, the students of this school could be used not only for church affairs, but also for Roman politics in the localities. Apparently, Euphrates was one of them. And it is no coincidence that it was he who was sent by Emperor Justinian to convert the Abazgians to Christianity.140 Fulfilling this order from the emperor, he naturally spoke the native language of the Abazgians, which should have made it easier to achieve the goal. In a word, here we have precise information about how a secular person (if not a clergyman) for the purpose of missionary activity is specially sent to his monolingual environment for its conversion to a new faith. So, in our opinion, there is no doubt that sermons in the 6th century among some of the Abkhaz neophytes were conducted in their native language.

As for the official church language of the later period - the 7th-10th centuries, then, of course, it was Greek. The fact is that after the Arab Caliphate captured a vast territory that had previously been part of the Byzantine Empire in Asia, Africa, as well as Iranian possessions, Eastern Armenia, Caucasian Albania and Iberia found themselves under Arab rule.141 During this period, in particular, in Georgia, apparently, the Autocephalous Church did not function, since the Church of this country was then subordinate to the Antiochian center of Christianity within the Arab Muslim Caliphate.142 And Abkhazia and Lazika found themselves under the rule of Byzantium, since the border between the Caliphate and Byzantium passed along the Likhsky ridge,143 as a result of which The Laz Metropolis and the Sebastopol Autocephalous Archbishopric were directly subordinate to the Church of Constantinople.144 This is repeatedly stated by the aforementioned early medieval church ecthesis Notitiae episcopatuum. In such a situation, the language of the official church in Lazika and Abazgia was naturally Greek. Here you can also refer to the Slavic life of St. Constantine the Philosopher, which talks about the existence of Abkhazian writing and the use of the Abkhazian language in official church services.145 The life talks about how, to justify the translation of the Holy Scriptures into the Slavic language, St. Constantine (Cyril), during a discussion with Latin priests in Venice in the 9th century, lists the peoples who have writing and who pray in their own language. “These peoples are,” says the life, “Armenians, Persians, Abazgs (Abkhazians), Iberians, Sugds, Goths, Avars, Turks...”146 However, on the basis of this written source it is difficult to prove that the Abkhazians in the early Middle Ages had their main church language was the native Abkhaz language. Apparently, this requires additional written monuments. In connection with the issue that interests us, I would like to draw the readers’ attention to the fact that the famous Abkhaz archaeologist L.N. Soloviev repeatedly said that in Greece on the Holy Mountain (Athos) there are manuscripts written in Greek letters, but read in the Abkhaz language!

In our opinion, those authors who believe that Georgian could have been the official church language in Abkhazia, at least until the end of the 10th century, are also wrong. In particular, this idea was expressed in Moscow at the XIII International Congress of Historical Sciences by Francis Dvornik, although he immediately made a reservation that “of course, he does not exclude the use of the spoken language, at least partially, in Abazg worship.”147 It must be emphasized that the native language has always been a natural means of communication between the people, but the church language in Abkhaz worship until the end of the 10th century could only be Greek, for, as we indicated above, at that time the Georgian Church itself was subordinate to the Antiochian Church, which by that time was located on the territory of the Muslim caliphate, and the dioceses on the territory of Abkhazia were subordinate to the Patriarch of Constantinople.148 Therefore, naturally, Constantinople would not allow worship in the diocese under its care in the language of the people subordinate to the hostile Muslim caliphate. In a word, regarding the language of worship in the Abkhaz Church of the early Middle Ages, in our opinion, the following conclusion can be drawn: initially, as elsewhere, the sermon here was in the Abkhaz language, and with the advent of the official church pulpit - in Greek. This situation existed here at least until the beginning of the 13th century.

Regarding the consequences of the Christianization of the Abkhazians, the opinion was expressed in the literature that in those specific historical conditions it played a significant role.149 However, without denying the unconditionally positive role of the Christianization of the Abkhazians, in our opinion, one cannot identify the role and significance of Christianity in Abkhazia of that period with its role in others regions of the Caucasus, say, Armenia and Iberia.150 The fact is that, as we have already indicated above, the Armenians and Iberians (Eastern Georgians) during the struggle against the domination of Iran with its religion of Zoroastrianism saw Christianity as a powerful weapon of self-defense.151 And it in fact, played a progressive role in many respects in the life of these peoples. And the Abkhazians, who geographically bordered only Byzantium, accordingly, could not use this religion against any other expansion. The geographical position of Abkhazia itself did not allow this. Therefore, in our opinion, Christianity was voluntarily accepted in Abkhazia, mainly by privileged layers, people close to imperial circles, although it could also be accepted by other layers of society at the call of their spiritual needs.

In subsequent times, the Christianization of Abkhazia and, in particular, the activities of the Church could not but play a positive role in the development of spiritual culture. This concerns, first of all, the construction of religious monuments based on projects, first of all, of the Constantinople royal workshops,152 fresco painting and objects of religious ritual, etc. But the Christian religion itself, with its preaching of high morality and purity, undoubtedly played a positive role in the formation of the spiritual culture of the Abkhaz people, their high mentality, and the development of ethical standards - Apsuar. Moreover, according to the observation of Denis Chachkhalia, the traditional culture of the Abkhaz people is largely permeated with Christianity.153 On the other hand, apparently, the integrative activity of the monotheistic religion to some extent contributed to the unification of the Abkhaz peoples, strengthening their ties with Byzantine civilization, first strengthening the foundations of the principality, and then and the creation of a unified Abkhaz monarchical state.

Apparently, this chapter completely rejects the idea, circulated in the press by Georgian historians and the clergy, that the Abkhazians allegedly received Christianity from the Georgians. In addition, they use this idea for the purpose of expanding Abkhazia. For example, a representative of the Georgian clergy, Bishop Kirion, when asked why Abkhazia should certainly enter the autocephalous Georgian Church, answered: “Georgia enlightened them (that is, the Abkhazians) with Christianity and has the right to govern them.”154

The Abkhaz Church has stopped services: are the chances of recognition increasing?

The head of the Abkhazian Orthodox Church, Priest Vissarion Apliaa, said that services in churches in Abkhazia are suspended until the status of the Abkhazian Orthodox Church is determined.

Services continue in the cathedral in Sukhum, other churches are open to parishioners, but no services are held.

“We hoped and hope that the Moscow Patriarchate will solve our church situation, the status of our Abkhazian Orthodox Church. We cannot be part of the Georgian Church, we have not been part of the Georgian Church and will not be,” said Priest Vissarion.

He also expressed hope that the canonical status of the Abkhaz priests who were ordained in the Russian Orthodox Church will be determined and they will return with status for the Abkhaz Orthodox Church.

“To be in some kind of situation like this for thirty years is impossible. Therefore, I have now suspended services,” said the head of the AOC.

The AOC website provides an outline of the Orthodox history of Abkhazia, which notes that the Georgian clergy of the Sukhumi-Abkhaz diocese were on the side of those who brought tanks into Abkhazia in 1992 and started a war. Metropolitan David (Chkadua) in August 1992, together with Eduard Shevardnadze, on the square near the building of the Council of Ministers of Abkhazia, welcomed the seizure of Sukhum by Georgian gangs. A few days after appearing on television, where Metropolitan David called on Georgians to go to war with the Abkhazians, he died in Tbilisi under unknown circumstances.

Daniel ( Datuashvili was sent to Sukhum , who, like his predecessor, continued to inspire the Georgian “warriors” in the war with the Abkhaz people. After the liberation of the city of Sukhum by Abkhaz troops in September 1993, Archbishop Daniel, along with the Georgian clergy, fled to Georgia (leaving the Christian flock of Abkhazia to their fate), where he still nominally bears the title of bishop of the Sukhumi-Abkhaz diocese. In Tbilisi, Metropolitan Daniel is an active participant in all events carried out by the so-called government of the Abkhaz Autonomous Republic in exile. He also participates in all Georgian-Russian church events as the head of the Sukhumi-Abkhaz diocese, the AOC notes.

After the flight of the Georgian clergy, four priests remained in Abkhazia, including priest Vissarion Apliaa. At the end of 1993, the above-mentioned clergy elected from their midst priest Apliaa as rector of the Cathedral of the city of Sukhum and representative of the Sukhumi-Abkhaz diocese in relations with the state and the Russian Orthodox Church.

“In the post-war period, several churches and monasteries were opened on the territory of the Sukhumi-Abkhaz diocese. The New Athos Monastery was opened in 1994, and the Kamansky Monastery in 2001. The New Athos Theological School has been operating since 2002. The number of Abkhaz clergy was replenished with young educated hieromonks. Worship services in the Abkhaz language have been resumed,” the essay says.

The statement by the head of the Abkhazian Orthodox Church, Father Vissarion, caused a resonance, the telegram channel “Abkhazia Center” comments on the situation.

“In light of the ideas of a union state, as well as the outcome of political unrest in Georgia that is unfavorable for Russia, the chances of recognition of the status of the Abkhaz church are increasing,” the authors of the Abkhaz telegram channel hope.

Search for enemies of the people

An appeal to Bartholomew regarding the independence of the Abkhaz Church was signed by 25 deputies out of 35 members of the Abkhaz parliament, and a survey of citizens began in support of the idea. According to schismatics, the issue can be resolved by the heads of the five oldest Orthodox churches or the Ecumenical Council. Not a single canonical document, of course, says that five churches can independently resolve the issue of autocephaly. And they have been trying to convene an Ecumenical Council of Orthodox Churches for about 50 years, but they cannot because of organizational contradictions. And they are unlikely to be able to in the coming years. I think that this is well understood by the opponents of the Abkhaz diocese, who in fact had a completely different task. Is it a coincidence, but from the text of the questionnaire it follows that only the Georgian and... Russian are against the independence of the Abkhaz Church. It seems that the anti-Russian nature of the survey itself was more important than anything else. In public speeches, the initiators of the survey who did not want to participate in it called them enemies of the people.

Article on the topic

Yuri Belanovsky: How has the church changed in 25 years? But the main work took place in the quiet of the offices. The schismatics were able to legitimize the schism by registering the charter of the metropolis with the Ministry of Justice of Abkhazia. The authors of the charter deliberately veiled the main question: on the basis of which church is the “Holy Metropolis of Abkhazia” registered? Although in fact the charter refers to the New Athos Monastery - while the monastery, according to the resolution of the Cabinet of Ministers of Abkhazia, back in 2010 was transferred to the Pitsunda and Sukhumi diocese of the Abkhaz Orthodox Church for free and indefinite use. Officials of the Ministry of Justice either did not study the charter before registration - otherwise they should have demanded that the illegally occupied monastery be vacated. Or... this could not have happened without the knowledge of the top leadership of the state, President Alexander Ankvab, and contrary to his own recent statements. At the Second Russian-Abkhaz Humanitarian Forum, he said that the close historical ties of Abkhaz and Russian Orthodoxy give him reason to turn specifically to the Moscow Patriarch with a request to ordain an Abkhaz bishop. But with the decision to register the metropolitanate, the Abkhazian authorities completed the split of the Abkhazian Orthodox Church.

Operating monasteries of the Abkhaz Diocese

Monastery of the Holy Apostle Simon the Canaanite in New Athos.

The rector is Hieromonk Andrey (Ampar). Number of inhabitants – 25 people. There are two churches on the territory of the monastery: the Cathedral of the Holy Great Martyr Panteleimon and the Church of the Martyr Hieron. Address: Gudauta district, New Athos, monastery. Tel. +7 (840) 227-19-71. The monastery is open to the public every day from 12.00 to 19.00, with the exception of Mondays and Lent.

Monastery of St. John Chrysostom in the village of Kaman.

The rector is Hieromonk Dorofey (Dbar). Number of inhabitants – 5 people. There are two churches on the territory of the monastery: the Church of St. John Chrysostom and the Church of the Martyr Basilisk. Address: Sukhumi district, Kaman village, monastery. Tel. +7 (840) 227-25-04.

Analysts have ruled out the possibility of ROC recognition of the Abkhaz Church

The Russian Orthodox Church will not recognize the Abkhazian one as part of it, as it values the support of the Georgian Orthodox Church in the confrontation with the independent Ukrainian Church, analysts interviewed by the Caucasian Knot are sure. The head of the AOC Vissarion Aplia changed his decision to suspend services in churches after a conversation with Moscow.

As the Caucasian Knot reported, services in churches in Abkhazia, with the exception of the Cathedral in Sukhum, have been suspended since February 20. They will not resume until the status of the Abkhazian Orthodox Church is determined, said the head of the AOC, Priest Vissarion Aplia. Parishioners of Abkhaz churches expressed regret over the cessation of liturgies.

After the end of the 1992-1993 war, Abkhaz priests assembled a diocesan council and elected Vissarion Aplia as temporary administrator of the Sukhumi-Abkhaz diocese, in whose churches, with the blessing of the bishops of the Russian Orthodox Church, priests from Russia are currently serving. The course and results of military operations in Abkhazia are described in the material of the “Caucasian Knot” “War in Abkhazia (1992-1993): main facts.”

Priest Vissarion Aplia, after consultations in Moscow, decided to resume services in all churches of Abkhazia after the return of clergy who were sent to Russian dioceses. A representative of the Abkhazian Orthodox Church told the “Caucasian Knot” correspondent about this on the evening of February 26.