Where does a mortal man have wings on the icon?

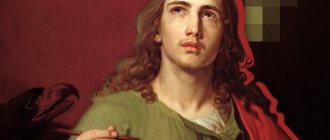

This widespread image of John the Baptist was called the “Angel of the Desert.”

The wings behind the back of John the Baptist are a symbol of his life as equals with the angels. From the Gospel we know that John lived in a deserted place, dressed in camel skins and ate locusts. According to one interpretation, locusts are the fruits of the carob tree; according to another, an edible variety of locust. — Approx. ed. and wild honey. Reading these lines, we imagine a very harsh, essentially monastic life, which was led by the hermit and ascetic John the Baptist. It is not for nothing that the Church considers him the spiritual patron and forerunner of all monastics. It is no coincidence that the icon we are talking about depicts a desert and a mountain, and in the hands of the Forerunner is a charter. This is what sheets of papyrus were called in ancient times. — Approx. ed. with the inscription: Repent, for the kingdom of heaven is at hand (Matt. 3:2).

Saint John the Baptist Angel of the Desert, c. 1700

And the biblical basis for the angelic iconographic image of John the Baptist is a well-known passage from the book of the prophet Malachi: Behold, I send My angel, and he will prepare the way before Me, and the Lord will suddenly come to His temple (Mal 3 :1). Christ himself directly connected this prophecy with John the Baptist (Matthew 11:10 and Luke 7:27 ).

In the troparion, which is usually read to the monk, there are the following words: “Desert inhabitant and in the body an Angel.” That is, a monk, a reverend, is both an angel and a man; This is the ancient church understanding of the essence of monasticism. It is this similarity with the angelic way of life that is reflected in the icon.

Saints icons

The icons are attributed to the Novgorod school and date back to c. 1400

The two icons reproduced here were part of the order, which, as we saw from the analysis of the iconostasis, occupies one of the most important places in it in terms of its significance. Therefore, as a rule, icons of this tier were made larger than icons of other tiers. Our icons (the first - 177x64 cm, the second - 177x66.5 cm) obviously belonged to one of those iconostases that were distinguished by their grandeur. The role of the iconostasis, designed to be visible at one glance, greatly contributed to the development of simple and clear compositions, strength of color and generalized lines, giving the figures a special silhouette characteristic of Russian icons. Otherwise, the icons would be difficult to see and distinguish, especially in large churches, at great distances and heights. These requirements of silhouette and clarity are fully met by the icons of St. Basil and St. Vmch. George. Their monumental figures, perfectly inscribed in the narrow shape of the board, are strictly proportional. Painting is distinguished by a sense of colors, bright and harmonious. They are written with great force, easily and freely, without any pressure or effort. The colors are either dense, lying in a continuous spot (as, for example, in the fiery cloak of St. George, the white omophorion of St. Basil and the backgrounds), then light and transparent, with light highlights (as in the undersides and phelonion of St. Basil), creating the play of planes gives the icons greater liveliness.

The drawing is precise and expressive. Rhythmic lines, sometimes long, melodious and soft, sometimes short, angular and sharp, echo each other, being no less an essential means of expression than paint. Almost motionless in appearance, the figures of saints are full of a special inner life. Their inner calm concentration is conveyed by tilting their heads and stooping. Their poses are natural and free; they walk lightly, barely touching the ground with their feet, and if it were not for the high ground, their figures would seem torn off the ground and floating. Both icons were painted by the same master, who has great artistic culture and extraordinary technical experience.

Saint Basil the Great, as a bishop, that is, the successor of the apostles, follows in rank directly behind them as Holy Martyr. George follows the venerables and usually brings up the rear. Judging by the rotation of the figures, the place of our icons was not on the side on which they are placed in the iconostasis, reproduced on p. 104

, and on the opposite.

St. Vasily the Great, martyr. Georgy. From Deesis. Novgorod. Around 1400. Kellyken Collection. Amberg (Ggrmania)

Saint Basil the Great is depicted, as bishops are usually depicted, in full vestments, with the attributes of his episcopal dignity. On top of his phelonion on his shoulders is placed a falling omophorion with crosses, “with the help of which he represents the incarnate Son of God”219, or, according to the interpretation of St. Herman, “the omophorion with which the bishop is vested signifies the lost sheep, which the Lord, having found, took upon His shoulder <…>. For this reason he also has crosses, just as Christ bore His cross on His shoulders...”220 As the successor of the apostles and teacher of his Church, he holds the Gospel in his left hand, while his right hand is extended in prayer to the one sitting in the center of the rank

To Christ. Figure of St. Vasily is full of majestic calm. His high, convex forehead bears the stamp of concentrated, deep thought. Before us is the image of a teacher of the Church, a great theologian, interpreter of the mystery of the Holy Trinity.

Saint George is depicted in the traditional red cloak for a martyr and a blue chiton with a greenish tint. His depictions are varied: he is depicted either on horseback, slaying a dragon (see illustration on p. 210), or as a foot warrior. He is also depicted as a military tribune - in patrician robes, with a metal diadem on his head, with chain mail under his cloak, holding a cross with his right hand and a sword with his left. Here, in rank, neither he nor the other holy martyrs are ever depicted in their military dignity and with weapons in traditional icon painting. Since, as we said when analyzing the iconostasis, rank is an image of the normal order of the universe, the order of the next century, it is obvious that there is no place in it for any hostility, and therefore for weapons. If St. Basil the Great is depicted in the service for which he was glorified, for his life which was his feat, then St. George is portrayed as glorified for his death - as a martyr for the sake of Christ, for his earthly service was only the path to heroism221.

Georgy. Mosaic icon. XII century Monastery of Xenophon. Athos

Martyrs in Orthodox iconography are not depicted with the attributes of their torment, because what is important for the Church is not how and with what they were tortured, but what they suffered for.

It should be noted here that images of torture are found on icons of saints extremely rarely (for example, the beheading of John the Baptist). When they are depicted, they are placed in the so-called stamps on the sides of the icon of the saint as a secondary, additional element. In other words, in the icon, as in the service to the saint, the center of gravity always lies not on the torment and burden of achievement, but on the joy and peace that are its fruits.

The beheading of John the Baptist. XVII century Stroganov school. Museum of Icons. Recklinhausen (Germany)

The Torment of St. Paraskeva with fire. Mark from the icon of the Martyr Paraskeva Friday in the Life. Russia. XVI century Pskov Museum-Reserve

In the icons of St. Basil the Great and St. The images of the Great Martyr George attract special attention both for their internal content and the manner of execution. Just like the figures of the saints, they are painted with extreme spontaneity and precision. Greenish with a brown tint, sankir (base tone) is laid lightly and transparently. In some places the white background of the board shines through, creating a play of shadows and giving them depth and transparency. On this rather dark sankir, in a loose, dense flow, two highlights are laid in succession: the first is from yellow ocher with red, the second is from yellow ocher with white. The processing of the form is completed with strong, bold and precisely placed animations. They are made with pure white and laid in such a way that they smooth out and cover the uneven edges of the melt. Dark hair of St. George are highlighted with golden ocher; at St. For Vasily, they, like his beard, lie as a solid spot, broken up by several strokes of darker paint. In general, the technique is simple, confident and powerful and resembles the fresco technique. It is somewhat rough, but strong and precise, with great painterly scope. There is no severity in the faces of the saints. They attract with some kind of “motionless” peace, and at the same time it is difficult to determine the more forward movement is conveyed - whether by the body, prayerfully outstretched hands or eyes. The faces and eyes of saints, that is, that which expresses the highest focus of a person’s spiritual life, show the complete power of the spirit over the body, especially characteristic of the Russian icon.

St. Basil the Great. Icon detail. Novgorod. Around 1400. Kellyken Collection. Amberg

This is a kind of figurative expression of the words of the troparion, which is sung instead of the Cherubic song of Great Saturday: “Let all human flesh be silent <...> and let it think of nothing earthly within itself.” Both faces of the saints breathe this absence of thoughts about earthly things in the flesh enlightened by the Holy Spirit and brought to silence. They are devoid of carnal heaviness and full of spiritual serenity. Particularly characteristic is the face of St. George. He is not devoid of anything characteristic of human nature, and at the same time, when you look at him, it seems that you see in front of you the face of not a man, but an angel (see pp. 59–60).

Humanly courageous, strong-willed and strong, he amazes with his unearthly purity and calmness.</…>

St. Martyr. Georgy. Icon detail. Novgorod. Around 1400. Kellyken Collection. Amberg

What amazing theological thought lies behind the image of the “Angel in the Desert”?

The image of the “Angel in the Desert” appears around the 13th century and becomes especially common in the 14th century. In Russia it was written, for example, by Theophanes the Greek. It was precisely at that time that the theological teaching of hesychasm (from the Greek ἡσυχία - silence, silence) took shape, speaking about the possibility of transformation, the deification of man. Saint Gregory Palamas finally formulated the idea expressed back in the 7th century by Maximus the Confessor, that a person is able to enter into direct communication with God through His uncreated energies, is able to see the Light of Tabor.

Sometimes the second head is depicted at the feet of the saint. John the Baptist, Byzantium, mid-15th century.

And according to the Monk Justin (Popovich), who lived quite recently, in the 20th century, the entire gospel of the Old Testament consisted in the fact that man is an icon of God, created in the image and likeness of God (cf. Gen. 1:26 , 27). The gospel of the New Testament sets a new, much higher ideal of the God-man. After the incarnation of Christ, man’s task is not just to keep within himself the image and likeness of God, but to reveal them to the end, to follow Christ and become a God-man. As Saints Athanasius the Great and Irenaeus of Lyon wrote even earlier, God became man in order for man to become god.

The image of John the Baptist, an ascetic and hermit, is perfectly suited to express this idea.

Brief biography

Six months before the birth of God’s Savior, John the Baptist appeared to the world. He was a late, long-awaited and begged-for child in the family.

The young man spent his youth in an ascetic lifestyle; he lived in the desert for a long time. And at the age of 30, he began preaching and called people to faith and repentance in the Judean desert. His sermons were terse, but had great power: all of Judea came out to him and received Baptism in the waters of the Jordan.

Read about the Baptist of the Lord John:

- Akathist to the Forerunner of the Lord

- Relics of Saint John the Baptist

John appealed to the fact that baptism from him is a preparation for receiving the Savior Jesus Christ. It is He who will soon come, take upon himself all the sins of humanity and destroy hell.

In his preaching works, the saint was not afraid to expose the sinful relationship of King Herod with his brother’s wife Herodias. For this he was taken into custody in the fortress and awaited his imminent execution. But the king was afraid of possible popular anger, because people revered him as a prophet. Herod's fear overpowered the hatred of Herodias, who was trying to kill the saint by any means.

One day she had a chance: on Herod’s name day, Herodias’ daughter Salome entertained the guests with sophisticated dances. The king really liked his niece’s dancing, and he invited her to ask him for everything she wanted. The mother persuaded her daughter, and Salome demanded the head of John the Baptist on a platter from Herod.

A squire was immediately sent to the prisoner’s dungeon, he beheaded the Baptist and gave his honest head to the girl on a platter. This day is celebrated annually in the liturgical calendar as the feast of the Beheading of John the Baptist.

Prophet, Forerunner and Baptist of the Lord John