A healthy lifestyle is very popular today. It is advertised on television, on the Internet and on the streets, many gyms are opened, many are trained as trainers and begin to lead people to an ideal body. Along with the usual physical activities, many alternative and foreign sports options are emerging: martial arts, Pilates, and, of course, yoga.

It is about the last option that disagreements arise, because yoga is not only sports activities, it is also a certain worldview of a person and spiritual practices. What is the attitude of the Orthodox Church towards yoga and is it possible for an Orthodox person to practice it?

The position of the Orthodox Church towards the teachings of yoga

The Orthodox faith does not imply the performance of any specific actions or movements, similar to asanas in yoga. Nevertheless, there are many people who consider themselves Orthodox, but at the same time practice yoga.

Since most people in Russia are considered adherents of the Orthodox Church, it is necessary to think about what Orthodoxy thinks about yoga. Most Orthodox priests speak rather negatively about when a person takes the path of yoga practice. But some modern priests can express a positive point of view. It must be remembered that this is a purely individual reaction of each individual church minister and it is almost impossible to determine a single correct position.

Nevertheless, it is possible to identify the main negative points for which Orthodoxy and yoga are considered incompatible. Among them, the most common ones are:

- many supporters of Orthodoxy highlight the negative impact of meditation, calling it a “near-religious” aspect in yoga;

- it is necessary to distinguish between an adherent of the practice of yoga as a physical exercise and as a philosophy, worldview and religion;

- unexplored abilities of practice and their influence on the human mind;

- the difference between Orthodox canons and commandments and Ayurvedic ones;

- difference in nutrition and fasting;

- the difference in man's acceptance of God;

- the difference in the feeling of energy.

There is a branch of yoga called kundalini yoga. In general, kundalini is a specific energy that flows in the human body and is vital. In this case, yoga implies the beginning and concentration of it near the base of the spine, that is, the area below the heart. The Orthodox Church believes that sensations during reading prayers or requests to God should not be below the heart zone. If this happens, then it is necessary to reject such sensations. Thus, many aspects of Orthodoxy and yoga are practically incompatible.

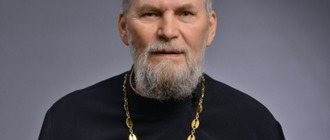

Patriarch Kirill’s opinion is that yoga can complement Orthodoxy if a person engages in it as a physical activity, but continues to believe as an Orthodox person and adhere to all the canons of this faith.

Orthodox Life

Pravoslavie.Ru

To be convinced that yoga is now a very fashionable and widespread phenomenon, just walk down the street somewhere in Moscow, St. Petersburg, Volgograd, Kaluga or any other large city. You will definitely catch your eye, if not the signs of yoga centers themselves, then their advertising. You can go not on the street, but on the Internet. Yandex for the query “yoga” will give you more than 850 million results, and for the query “Orthodoxy” - 474 million - almost half as much.

After the Soviet Union with its godless ideology was destroyed, it was not replaced by any other. On the contrary: the state announced that from now on it will not support any ideology. But that doesn't happen. The absence of ideology is also a certain ideological attitude, and it contributed to the unprecedented proliferation of everything that had been suppressed and restrained by state pressure for decades. The Church also came out of hiding. But the minds and hearts of a large part of the former Soviet citizens were captivated by other phenomena and teachings, whose representatives also came to the surface and immediately began to declare and talk about themselves on television, on the Internet, print and other media: psychics, magicians, astrologers, fortune tellers, adherents of unconventional medicine and, of course, yoga...

What do yoga and materialism have in common?

What brings people to yoga? In my case, it was a craving for something mysterious, for a teaching that showed the way to mastering superpowers: telepathy, breath-holding, etc. I first became acquainted with yoga in elementary school thanks to my older cousin. Even then, in the early 1980s, I sat in class in the lotus position, and the teacher made comments to me and asked me to sit “like a human being.” My last mentor was a fitness yoga instructor, with whom back in 2008–2009 we intensively restored the basics of Ashtanga yoga, which had been largely forgotten during my office work. Between these two “teachers” there were many books, groups, seminars and teachers.

After thirty, I became interested in getting to the bottom of yoga, and the place of physical exercises - asanas - began to be increasingly occupied by meditative practices. The fact is that if a person takes up yoga and doesn’t quit, then sooner or later he will discover that sitting in the same poses day after day, doing the same exercises is boring. One day he will inevitably be faced with the question: why is all this necessary? So it was with me: I began to look for meaning. And one day I learned that in Hinduism there is such a concept - pralaya, which means (to simplify somewhat) the cyclical destruction of the entire universe. It doesn’t matter what you did (yoga or something else), what you strived for, how many times you were born and what class or caste you belonged to - in the end, all souls, whether they want it or not, will unite in some kind of “golden egg”, into which the entire universe will collapse, when once again the “day of Brahma” will be replaced by the “night of Brahma.” The end of the universe will happen and everything will disappear. From the point of view of a yogi, the immortality of the individual soul does not exist - with the beginning of a new “day of Brahma,” souls will arise again, but completely different ones, not those that were destroyed. Only the impersonal absolute – Brahman – is immortal.

All this has many similarities with the materialistic picture of the world, the “theory of a pulsating universe,” etc. Although in Hinduism, of which yoga is a part, there are many directions - from almost atheistic and agnostic to pantheistic, recognizing many gods and close to paganism.

Then what is the goal of the yogi? He strives to achieve the state of samadhi and moksha - “liberation”. This is liberation from existence, from being itself, which the yogi understands as complete suffering. The yogi believes in reincarnation, in numerous rebirths, but he does not strive for them at all, but, on the contrary, tries in every possible way to avoid them, because for him all this is just an increase in suffering.

When I realized that, from the point of view of yoga, death awaits a person in any case, and not only physical, but also the death of the soul (the cessation of its rebirths and merging with the indifferent absolute), this ceased to be interesting to me. A little later, in the summer of 2010, for the first time I “accidentally” ended up in the St. Paphnutiev Borovsky Monastery, and from then on my life began to change.

Why yoga cannot be non-religious

Why not practice yoga simply as gymnastics, without plunging into its mystical and occult depths? I am deeply convinced that this is impossible (unless someone is “lucky” and the passion for yoga turns out to be fleeting). Yoga is part of the Hindu religion, and there is no escape from it. The word yoga itself comes from the Sanskrit yuj, which means “to connect, to bind.” And “religion” comes from the Latin religare: “to bind, to unite.” In both cases, it is meant that a person establishes a connection with God - or with some other forces, invisible, but capable of interacting with him. Thus, to say that yoga is non-religious is at least illogical: “yoga” and “religion” are practically synonymous. Another thing is that people rarely delve into the meaning of words.

On websites dedicated to yoga, you can find quotes from the Gospel, statements that Christ Himself was a yogi, and the like. This is said with reference to those “Orthodox” but not churchgoers, of whom the overwhelming majority are in Russia. The statistics here are well known: 70–80% of Russians officially consider themselves Orthodox. However, those who receive communion at least once a year are less than 30%. And the true children of the Church who know the Creed, lead an active church life and regularly receive communion are less than 5%. And, of course, yogis use certain elements of the similarity of their teaching with Christianity to attract into their camp these “liberal believers” who recognize themselves as Christians and, perhaps, even sincerely want to be one, wear crosses, but know practically nothing about Christ, nor about His Church.

The question of what is the fundamental difference between Orthodoxy and yoga began to worry me after visiting the St. Paphnutiev Borovsky Monastery. I kept asking spiritual mentors then: “Can I do yoga? Why not?” And if they confidently answered the first question, they somehow avoided answering the second. I wanted to figure it all out, first of all, for myself. Over time, this turned into a seminar topic, and now into a book called “Yoga. Orthodox view”, which the publishing house “Symbolik” plans to publish in the near future (the stamp of the Publishing Council of the Russian Orthodox Church R18-812-0445 was provided on August 9, 2018).

About superpowers and humility

At first glance, the ethical principles of yoga are very similar to the biblical commandments. The principle of Ahimsa (non-violence) seems to be equivalent to the commandment “Thou shalt not kill.” Brahmacharya (sexual abstinence) is almost the same as “Thou shalt not commit adultery.” Asteya (non-appropriation of someone else’s property) is the same as “Thou shalt not steal.” But here is what St. Gregory Palamas said about such similarity: “A lie, not far from the truth, creates a double delusion: since a tiny difference eludes the majority, either a lie is mistaken for the truth, or the truth, due to its close proximity to a lie, is mistaken for a lie, in both cases completely falling away from the truth.” These words accurately describe the situation with Christianity and yoga: the difference becomes noticeable when you start to “put everything into pieces.”

You may not immediately notice this, but in yoga there is no commandment about humility. Not at all. Perhaps the yogis themselves will begin to argue with this, but there is a fact: in the key source on yoga - the Yoga Sutras, in their ethical section - not a word is said about humility. And in Christianity, the commandment of humility is fundamental. Blessed are the poor in spirit (Matthew 5:3) - the Savior’s Sermon on the Mount begins with these words. And without humility, no virtue has any value.

From personal communication with some yoga adepts I respect, I came away with the idea that for them, the absence of pride is, of course, great, but it is needed at the very top of “spiritual ascent.” In the meantime, in order for your progress to be faster, you need motivation, which also comes from pride. The ego becomes the “engine of progress.” And humility seems to be necessary, but not now: first we will go through all the other stages of the path to “holiness”, and finally we will get rid of pride. But will it be possible?

Therefore, Christians begin with humility - from the very beginning they rely on the will of God, and not on their own.

Someone will object: pride motivates a person to achieve more and more, and a yogi (at least in the classical version) strives for the cessation of existence - a goal that seems to be inconsistent with pride. Here we must answer, firstly, that now “classical” yoga as such does not exist not only in Europe, but even in its homeland, India. I admit (although I don’t really believe it) that somewhere in the Himalayas there are two or three gurus who practice “true” yoga. But in general, yoga is a rather motley collection of different schools and directions. Some of them have an understanding that mastering superpowers feeds pride and does not help, but rather even hinders spiritual advancement. True, then the question arises: why do the same “Yoga Sutras” pay such attention, an entire section, to these superpowers?

And not only “Yoga Sutras”

The Fall of Adam and Eve

In the 1960s, the film “Indian Yogis: Who Are They?” was released on the screens of our country. Yoga was presented by its authors as philosophy, moral teaching and health-improving gymnastics. This film contributed to the popularization of yoga in Soviet society - as did inspirational publications about yoga in Soviet popular science magazines, the novel “The Razor's Edge” by Ivan Efremov and some other events in Soviet culture and art. But here’s what’s interesting: in the modern continuation of this film, released under the title “Indian Yogis: Who are they? 40 years later,” it says bluntly: yoga is a tool for “awakening energy and gaining superpowers.” Previously, this side of yoga was not so emphasized. And today, obviously, this is exactly the kind of yoga advertising that works.

A person wants to become like God, and this is normal. The only question is which way he goes. Adam, fulfilling the commandment of God, could remain immortal and over time become like God, cultivating the world entrusted to him by God and improving in love. But he chose the easy way - to become “like the gods” by eating the fruit from the tree of the knowledge of good and evil. Having done something “magical”, not blessed by God, something “besides God”. And many perceive yoga in the same way - as an entrance to the spiritual world “from the backyard.” In Christianity, I must fulfill moral commandments, fast, go to church - but why? I’d better go to a yoga center, do asanas and pranayama, meditate and get everything I’m missing!

Nevertheless, I hope that the Lord will one way or another bring those yogis who sincerely seek God to His Church - the only “ship of salvation.” I believe that even dedicated yoga practitioners have simply lost their way in their search for the true God. It seems to me that among them there may be a large number of future devoted children of the Church. They are searching, and not “lukewarm” (see: Rev. 3: 15–16).

The main area of divergence between Christianity and yoga is dogma. What is dogma from the point of view of the majority? This is something that the Church calls me to believe in, without proving or justifying anything. But yogis also have their own dogmas, what they believe in unconditionally. And these fundamental attitudes of yogis are completely different from those of Christians.

Christians believe in a Personal God

This is quite difficult to understand: Christians profess faith in one essentially, but trinity in the Persons of God: Father, Son and Holy Spirit - the Trinity, consubstantial and indivisible. In the Trinitarian and, moreover, the One Personal God. This is difficult even for Christian reasoning, and from the point of view of most yogis and Hindus, the highest principle is, in principle, not a person. Hindus recognize the existence of intelligent spiritual beings, they even call some of them gods, but they think of the highest principle - Brahman - as something impersonal.

Christians believe that there is only one life

Bosom of Abraham

The idea of reincarnation, widespread among the yogic community, contradicts all Christological dogmas and is in opposition to Christian ideas that life is given to a person only once, and then death, subsequent resurrection and judgment (see: Heb. 9: 27).

This is the most important idea, which the Church did not even approve as a dogma - simply because it never occurred to any Christian to doubt it. Among the first arguments traditionally given by defenders of the doctrine of reincarnation of souls is its supposedly widespread prevalence and imaginary antiquity. Christianity, they say, arose “only” 2000 years ago, and people believed in the transmigration of souls thousands of years before the birth of Jesus Christ.

But neither the ancient Greeks, nor even the Latins, as far as one can judge from the surviving monuments, had such ideas in their primordial tradition. What their real views on posthumous existence were can be seen from mythology, the most ancient examples of which go back to Homer and Hesiod: after the death of a person, his soul descends into the gloomy underground kingdom (Hades, Erebus, Tartarus), where it drags out a joyless, semi-ghostly existence. The ideas of metempsychosis (Greek: “transmigration of souls”) arose only in the times of Pythagoras and Plato (that is, in the 6th–4th centuries BC), and they were shared only by adherents of individual philosophical schools.

The ancient Egyptians mummified the bodies of the dead in the hope of a future union of their souls with flesh. The ancient Jews also had faith in the future resurrection of bodies, as evidenced by the famous prophecies of Ezekiel about the reunification and revival of dry bones (see: Ezek. 37: 1–14), Isaiah - about the resurrection of dead bodies (see: Is. 26: 19), the book of Job - about rebirth from the dust on the last day (see: Job 19: 25–27). There are no mentions of the transmigration of souls either in the Egyptian or in the Old Testament books.

The attitude of Christianity to the theory of reincarnation can be judged from the Gospel parable about the rich man and Lazarus: The beggar died and was carried by the Angels to Abraham’s bosom. The rich man also died and was buried. And in hell, being in torment, he raised his eyes and saw Abraham in the distance and Lazarus in his bosom (Luke 16:22-23). The narrator of this parable - the Lord Jesus Christ - clearly testifies that after death human souls do not move from body to body, but, as St. Nicholas of Serbia notes, “they move to the monastery that they have earned through earthly deeds.”

It is interesting that the idea of transmigration of souls was not initially characteristic of the ancestors of the Aryans. At least in the Rig Veda (1700–1100 BC) there are still no traces of the doctrine of rebirth.

Christians strive for eternal life in the Kingdom of Heaven

Photo: Anatoly Goryainov / Pravoslavie.Ru

And let us return again to ideas about the purpose of human life. Hindus strive to stop suffering, and Christians strive to live happily with God and for this happy life to be endless. The most important Christian idea of deification - the unity of man with God - is based on the awareness that both man and God are individuals. And if so, then when we unite with God, we do not become some part of His body or a cell in His body, not at all. We gain the potential opportunity to contemplate God and enter into communication with Him.

Yoga “no hassle”

And yet, there will definitely be someone who exclaims: “I don’t care about philosophy, or religious ideas, or other wisdom and troubles! Yoga interests me solely as a set of physical exercises that give practical results. As an effective training system. What, isn’t it possible to do yoga “just because”?”

But the fact of the matter is that yoga cannot be reduced to physical exercise. If you come to practice at a yoga studio, then be prepared for the fact that you will not only have to train your body, mastering various poses, but also perform various exercises to “expand your consciousness,” practicing special breathing exercises and meditating. The practice of yoga involves mandatory meditation!

Is there really no yoga at all without all this “spirituality”? It happens, but it’s not yoga anymore. There are many similar systems of exercises aimed at increasing flexibility, strength, and the body’s resistance to pathogens - in a word, improving health. Pilates, stretching and so on. And if you are interested in purely physical training, then it is better to look among these areas. And do not be tempted by yoga with its “spirituality”, which smells of sulfur.

The difference between Orthodoxy and Eastern religions

If yoga and Orthodoxy, according to Patriarch Kirill, are compatible in some way. So are yoga and Eastern religions compatible?

In order to get an answer to this question, it is necessary to delve deeper into the understanding of the term “Eastern religions”, because there are many of them. If, according to the view of the Orthodox Church, our spirit and human needs and desires must be pacified by suppressing our carnal lust, destroying sinfulness in ourselves. In the tradition of the East, not only the soul, but also the body predominates.

Adherents of Eastern religious movements believe that a strong and healthy body is proof of faith. In this regard, the soul and body are interconnected with each other.

Since yoga allows you to develop your physical abilities, namely flexibility, endurance, physical strength, we can say that it allows you to improve the human body. Therefore, such work on oneself benefits a person who is faithful to the Eastern religion.

Conflicting Goals

What is the essence of yoga? This is complete concentration on your own thoughts, feelings, immersion in yourself, in your world of the subconscious. In many eastern practices, in Buddhism and Zen Buddhism, the main goal is to achieve the state of nirvana. Just look at the Buddha statues in Thailand, for example. Almost everywhere we see Buddha immersed in a state of trance, either meditating or lying down on pillows.

As for Christianity, a person’s return to himself occurs exclusively through the acceptance of God, through life in Christ. The goal is not achieved by immersing oneself. St. Paul wrote that in order to be known by the Lord, you must be loved by him. Love, in turn, implies communication, relationships, but not self-absorption. In the case of yoga, we see the same egoism that is incompatible with the basis of Christian teaching. That is, both the goals and the ways to achieve them are completely different. In Eastern religions it is “know yourself,” and in Christian religions it is “know God in order to know yourself.” The difference is very significant.

The main reasons for the rejection of yoga by Orthodoxy

Many Orthodox people have been practicing yoga for many years and do not find anything reprehensible in it. Although there are situations when a person, being Orthodox, engages in this practice, subsequently begins to delve deeper into Buddhism, and subsequently he may have a desire to join the Buddhist faith.

It cannot be said that the church has an extremely negative attitude towards Ayurvedic practices. However, some moments are still impossible for the Orthodox.

In yoga, great importance is placed on human energy, with the chakras located along the line of the spine, starting from its very base. Likewise, the kundalini energy flows from its beginning. In Orthodoxy, all human good feelings should be located in the region of the heart. Thus, in this understanding of practice, we can say that they are incompatible as philosophy.

Also of great importance in the practice is the concept of one’s own sexuality, the disclosure of libido and sexual energy by women and men. Orthodoxy is extremely categorical about these concepts, considering them sinful.

The main unpleasant point in the Christian faith is meditation. It allows a person to relax and pacifies the mind, but according to one version, it is seen as self-deification. Because during meditation a person moves away from everyday reality, bringing himself closer to God and the Universe.

Another nuance is a person’s attitude towards prayers. A believer must pray, turning to God. At the same time, during meditation, yogis turn mainly to themselves, to their own soul.

The Christian faith also speaks negatively about yoga because during practice a person brings himself into an uncertain state of consciousness, thereby affirming demons within himself.

Are Orthodoxy and Yoga Different in Reality?

In understanding the physical body and exercise, the practice is healthy and has many positive aspects. Despite this, the Christian faith is somewhat negative about many aspects of the practice. There are reasons for this.

Orthodoxy believes that in general they are compatible, but taking into account some features. These directions may be compatible with a person, but he must understand that it is necessary to be careful about many aspects, namely, meditation, performing asanas and yoga as a philosophy in general.

Yoga settings

In order to use mantras correctly without harming a person’s attitude towards his own religion, one should understand the purpose of these two directions.

The main settings of the practice include:

- pit;

- niyama.

Their main purpose is to prevent the flow of energy, as well as the ability to do no harm. The main commandment in Orthodoxy is the commandment “thou shalt not kill.” One of the overlapping points is that they are comparable to the practice of yoga, since it also believes that it is necessary to bring only light and a state of bliss to oneself and the world around us.

Samadahi

Samadahi in practice is called the highest state of the human spirit. Yogis usually strive to achieve this state, but this requires very great effort.

Practice involves complete and constant control over your mind and feelings. If a person learns this and is able to concentrate on one thing, then his consciousness will be able to redirect to another concentration of the object.

There is a very thin line between reason and feelings, so this fact must be carefully controlled by a person.

Hesychasm

In the Orthodox faith there is the concept of “hesychasm”, which implies silence and peace. A kind of prayer, working on oneself in order to ascend to the Lord.

Repeated repetition of a special prayer to the Lord, while thoughts should be completely freed from any worldly attachments or thoughts. Thus, during this prayer, a person finds strength in himself and takes the path to God, cleanses his mind.

Few people choose this path and not all people are able to follow this path correctly. However, those who were able to achieve such a state of peace and bliss are canonized as saints.

Much in this prayer is akin to meditative practice, however, their focus is very different.

Why meditation is a negative phenomenon

Self-knowledge lies at the center of meditation; it distracts a person from vanity and turmoil, takes him into the world of images and colors. In the process of meditation, a feeling of peace comes, but at the same time, yoga involves concentration on knowing one’s own self.

Yoga is part of Hinduism

This is not a prayer in which one speaks face to face with the Lord. It is simply a search for oneself and the desire to ignite something in oneself that was not there before. People chase the peace that meditation implies and forget that in this pursuit one can forget that man is just God's servant.

Important! Yoga depersonalizes a person and erases God from his consciousness. This alone can give an Orthodox a clear answer that it is better to abstain from this practice.

A person stops praying, he begins to look for the peace that consciousness depicts for him. Moreover, meditation forces a person to accept and understand that he is God, and this contradicts the Commandments of God, which say that one is Lord.

A person who constantly engages in such practice will sooner or later repeat the sin of Adam - he will decide that he is no worse than the Lord God and will be overthrown.

“Salvation is accomplished not “in oneself and through oneself,” but in God,” says the theologian Hierotheus (Vlachos). But the master of Zen yoga Boris Orion claims that Zen or universal peace is freedom from religions where there is no God, and most importantly, it is turning to oneself. Isn’t that what the serpent in Eden told the first people?

So, yoga involves:

- the importance of experience, whether positive or negative;

- no distinction between good and evil;

- concentration on the human “I”;

- absence of God;

- achieving false peace;

- denial of the Lord.

Important!

Everything that this practice promotes—rest, peace, tranquility—can be found in the Lord, in complete humility and submission. An Orthodox Christian should not look for this in yoga. All slogans sound very tempting, but in the end they lead a person to self-destruction, denial of the Lord and complete spiritual collapse. A person can achieve peace and perfection only by coming to the Lord and submitting to Him.

What should a Christian do?

In the modern world there is practically no person who does not know about yoga. Many people, adherents of different religions, including the Orthodox, practice yoga and do not find anything sinful or inconsistent with the laws of the church in it. However, in order to work correctly with mantras, a believer needs to know many points.

If an Orthodox person wants to practice yoga, he should compare aspects of faith and practice and identify for himself the most compatible and possible.

As for food intake, for the most part, an Orthodox person has access to many different dishes, but not during fasting. Yogis rarely or practically do not eat meat. Thus, a middle ground can be found here.

A person engaged in practice needs to understand and accept that he is Orthodox, but practices of his own free will for his own health and does not harm anyone.

The most important thing in spiritual practice is what motivates a person: love for God or selfishness

If everything is so good and safe, then where does the idea of mystical yoga, with which spiritual life is incompatible, come from?

It's about a person's motivation. Some people build up their muscles to pose for masterpieces of art or clear away rubble after earthquakes, while others build up their muscles to snatch wallets in alleys.

The same is true with yoga. Professor A.I. Osipov often says in his lectures that supernatural powers can be achieved in two ways:

Osipov Alexey

Russian theologian

Godly. A person simply leads a righteous life, for which he receives the approval of the Almighty and special powers. God trusts this person and, without fear for those around him, gives him the ability to work miracles. Moreover, the abilities themselves are not a person’s end in themselves, but a by-product of his creative activity. This echoes Eastern ideas about bhakti yoga. Selfish. Man consciously strives only to acquire mystical powers. He is driven by base motives: pride, greed, fear of being worse than others.

In both cases, you can gain miraculous powers in the same way that any person can build muscles. But the fundamental question here is not what you are doing, but why.

In this regard, the Indian myth about King Hiranyakasipu is indicative. He achieved enormous strength through rigid asceticism, but directed all his abilities to destroy faith in God. He ended badly - killed by Nrisimha, the avatar of the Supreme Deity of Hinduism.

The Indian king Hiranyakasipu used the achievements of yoga for evil, for which he was severely punished by the man-lion Nrisimha

So it’s not so much yoga that’s bad as the wrong motivation. Eastern teachers themselves warn that practitioners should not get carried away with mysticism, these abilities will not lead to good.

Yoga in Orthodoxy

Not all people understand the real essence of yoga. After all, it consists not only in regular repetition of physical exercises. This is a whole philosophical doctrine, a belief of people based on a certain position.

If a person of another religion engages in practice, he should understand that he must use mantras in a certain way and perform certain technical features of the practice.

There is even so-called Orthodox yoga, which was created by the American Lorette Willis. She created a specific system of practice, which is based on combining it with the Christian faith.