What are icons

The word “icon” translated from Greek means “image”. An icon in Christianity is a sacred image of Jesus Christ, the Mother of God, saints or angels. It can also be an image of holy events in Christianity. The icon was painted in compliance with certain icon-painting canons (rules), and was also consecrated according to a special church rite. By consecrating icons of saints, the Church gives a blessing for their use. During the consecration ceremony, the priest reads special prayers and also sprinkles the icon with holy water.

Writing an Orthodox icon

Icon - image of the invisible heavenly world

There are many days in the Orthodox calendar dedicated to holidays in honor of one or another holy image. This may be a memory of the miraculous appearance of the image and special miracles given by God to believers through this image.

The icon (translated from Greek as an image) and the temple wall painting (fresco) depict the Lord Jesus Christ, the Mother of God, Angels and saints, as well as the events of Sacred history in artistic language. They symbolically express the dogmatic and spiritual-moral teaching of the Church. An icon is a shrine because it elevates the thoughts and feelings of those praying to what is depicted.

The Holy Evangelist John writes: The Word became flesh and dwelt among us, full of grace and truth (John 1:14). St. John of Damascus, giving a theological justification for icon painting, points to the great New Testament event of the Incarnation: “The incorporeal and formless God was once not depicted in any way. Now that God has appeared in the flesh and with human beings, I depict the visible side of God. I do not worship matter, but I worship the Creator of matter.”

Church Tradition tells us that the Edessa king Abgar V suffered from leprosy. He heard about the wondrous miracles that Jesus Christ performed, for rumors about Him spread throughout all Syria (Matthew 4:24). Abgar wrote a letter to Christ and sent his painter Ananias to make His portrait. But he couldn’t get the image right. The Savior called him by name and asked him to bring water and a towel (in Slavic - ubrus).

Jesus, having washed his face, wiped it with a towel, and the face of the Savior was miraculously imprinted on it.

King Abgar accepted the shrine with faith and reverence and was healed. This is how the first icon appeared in the Church, which is called the Image Not Made by Hands (Not Made by Hands). Later, this image was transferred from Edessa to Constantinople[1].

The first icons, according to legend, were painted by the Evangelist Luke. On them the holy apostle depicted the Mother of God. Among the Slavs, the first icon painter was Equal-to-the-Apostles Methodius, Bishop of Moravia, educator of the Slavic peoples. In Rus', the beginning of icon painting is associated with the name of the Monk Alypius, an ascetic of the Kiev-Pechersk monastery. His disciple Gregory (also a monk) painted many icons.

Being a shrine, the iconographic image brings the invisible grace of God to those praying.

In the history of the Church there are icons that became famous for many miracles. Among them: icons of the Savior, the Mother of God (Vladimir, Kazan, Smolensk, Iverskaya, Jerusalem, “Support of Sinners”, “Assuage My Sorrows”, “Three-Handed”, “Seeking the Lost” and others). There are many famous icons of saints: Nicholas the Wonderworker, healer Panteleimon, St. George the Victorious, Tryphon the Wonderworker and others.

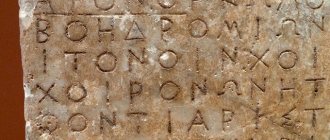

There are certain canonical requirements when creating icons. The icons of our Lord our Savior should have:

— name inscription: IC XC; a title is placed above each pair of letters (in Church Slavonic - a sign above the abbreviation of a word);

- a baptized halo pointing to the Calvary Cross, on which the Savior of the world made an atoning sacrifice;

- on the halo on the right, left and top there are three Greek letters - O (omicron), Ώ (omega) and N (nu), forming the word “Existing”. This inscription is of fundamental nature, since it indicates the Divinity of Jesus Christ. Jehovah is one of the names of God (see: Exodus 3:14).

The Mother of God in icons is always depicted in a dark red maforia. This is a large quadrangular board that covers not only the head, but the entire figure. The maforium symbolizes the motherhood of the Blessed Virgin Mary, and the blue tunic covered with the maforium (the color of heavenly purity) symbolizes Virginity.

Three golden stars on the maforia (on the forehead and shoulders) are symbolic signs of Her purity: before Christmas, at Christmas and after Christmas. Secondly, the stars are a symbol of the Holy Trinity.

The vestments (a necessary accessory to the vestments of clergy) indicate Her co-service in the Church with the Heavenly Bishop - Jesus Christ.

Nimbus (which means cloud in Latin) without a cross inscribed in it.

Abbreviated inscription: on the left MR (Greek Matir - Mother), on the right - ФU (Feou - God).

Nun Juliania (Sokolova; 1899-1981), who left a rich legacy, wrote about the close connection of the icon with prayer. Not only the creator of the icon, but also the one who perceives it must be a person of prayer: “An icon is a figuratively expressed prayer, and it is understood mainly through prayer. It is designed only for the believer standing in front of it in prayer. Its purpose is to promote prayer, so the worker in this matter must not forget about prayer while working. Prayer will explain much in the icon without words, make it understandable, close, show it as spiritually true, as irrefutably true.”

The meaning of icons in Orthodoxy

The icons of the Orthodox Church do not strive for naturalism and detail; the images on them are conventional and simple. Their purpose is for us to turn to the Prototype through a written image. When praying in front of an icon, a Christian worships and turns not to the painted board, but to the one who is depicted on it. The one who prays spiritually ascends to this person and unites with her. Icons of saints are a reminder of the higher, spiritual world and serve as a guide, a window into this world.

In the “Philokalia” you can find a statement by St. Theodore the Studite about the meaning of icon veneration:

“Whoever does not worship the holy icon of the Lord does not worship the Lord Himself.”

The grace of the one depicted on the icon also acts on the icon itself. Therefore, it is a shrine that should be treated with reverence.

The Monk Paisius the Svyatogorets spoke about the value of icons:

“When a Christian reverently kisses holy images and asks for help from Christ, from the Mother of God, from the saints, then he kisses with his heart, which absorbs not only the Grace of Christ, the Mother of God or the saints, but all of Christ or the Most Holy Theotokos or the saints , which stand in the iconostasis of his inner temple” (“Words”, volume 2).

Let us also quote St. John of Damascus from his “Words against those who reproach holy icons”:

“...after the death of them [the saints], the grace of the Holy Spirit abides inexhaustibly in their souls, and in their bodies, and in their features, and in their holy images.”

The icon has a theological, symbolic and aesthetic significance, but it also performs a missionary, liturgical function. Along with the Gospel and other shrines, icons are used in divine services. An icon is a manifestation of church tradition, because icon veneration is based on the recognition of basic Christian dogmas. For example, the dogma of the Incarnation.

In Old Testament times it was forbidden to depict the invisible and indescribable God. His written Image would be a blasphemous figment of human imagination. But the Son of God took on human form, became one of us, and now we can testify to this in icons. Therefore, icon veneration is also one of the dogmas of the Orthodox Church.

ICON

as a rule, 2-sided, participating in processions and associated with the tradition of venerating this particular image; during certain services (funeral, holiday services).

I. The emergence and formation of the type of external I. Interest in the study, primarily of 2-sided I., was due to the restoration discovery of the most ancient icons of Jesus Christ (Dobschütz. 1899. S. 79-85, 146-147) and the Mother of God (Anisimov. 1983 pp. 191-274). A.I. Anisimov associated the appearance of the image of the Cross on the back of the I. with the need to design the reverse side in the event of I.’s participation in processions. From this initial motif grew more detailed compositions involving the Cross: “Etymasia”, “Crucifixion”, “Adoration of the Cross”, “Christ in the Tomb”. Based on the study of texts, as well as the iconographic features of the surviving remote icons, certain provisions were developed about the influence of worship on their creation, especially the services of Holy Week (Volbach. 1940/1941. P. 97-126; Grabar. 1962. P. 363 -380; Idem. 1976. P. 144-147). According to D. Pallas and H. Belting (Pallas. 1965. S. 308-322; Belting. 1980/1981. R. 1-16), the iconography of these I., created for the Good Friday service, reflects the content of the service. N. Patterson-Shevchenko (Patterson-Shevchenko. 1994. p. 44) believes that the external icons that participated in the Friday night services in honor of the Mother of God (πρεσβείας) did not belong to a specific iconographic type, but were revered images of the Mother of God of large size , which influenced the special term adopted to designate them in the sources, e.g. in the Typikon of the Pantocrator monastery in the K-field, - σίγνον τῆς πρεσβείας.

Holy books Boris and Youth George pray in front of the icon of the Savior. Prayer to St. book Boris. Miniature from Sylvester's collection. 2nd half XIV century (RGADA. F. 381. No. 53. L. 123) Holy books. Boris and Youth George pray in front of the icon of the Savior. Prayer to St. book Boris. Miniature from Sylvester's collection. 2nd half XIV century (RGADA. F. 381. No. 53. L. 123) According to the hypothesis proposed by I. A. Shalina (Shalina. 2005. P. 584-585), the miraculous icon of the Mother of God “Hodegetria” from the monastery served as a model for the external I. -rya Odigon in K-field, a relic image that participated in processions that probably took shape already in the post-iconoclast period. This is confirmed by the fact that most 2-sided I. have on the front side an image of the Mother of God in the Hodegetria type, and on the back - the “Crucifixion” or scenes related to it. The placement of images on both sides of the I. was determined primarily by the placement of the revered I., like the shrines of the Cross, in specially designed spaces of the temple (under a canopy, a ciborium in a naos or in a separate chapel, but not in the altar) for ease of viewing and worship (There same. P. 579). As a rule, on both sides of the outer I., the I. revered in a certain temple and the image of the saint were reproduced. Special city processions were dedicated to such I., in which the revered I. of other temples could be carried. Those Byzantines were associated with the city lithiums. processional icons, the iconography of which went back to the capital's palladiums - icons and relics. In Russian cathedral worship, according to Russian. According to officials, I.'s participation in lithiums is recorded in the 16th and early 17th centuries, while the removal of relics in the procession dates only from the 2nd half. XVII century (Saenkova. 2007. P. 473). The tradition of two-sided worship, with their special place in the naos of the temple, was preserved for a long time both in Byzantium and in Rus'.

In the history of external icons, the reasons and time of their appearance, the principles of the formation of iconographic programs, the place in the temple and in worship, the reasons for the difference in the stylistic manner of execution of the two sides, etc. remain unclear. The difficulty in defining (and separating) different types of icons is partly due to with the lack of sources, especially from early times, with the impossibility of accurately identifying the surviving icons, which have signs of veneration, with those known from written sources as external icons. The issue of moving icons poses a certain difficulty, when, for example, a revered external image is placed in a local row of the iconostasis , losing the elements of the processional I. Thus, for example, on the lower field of the icon “Savior’s Ardent Eye” from the Assumption Cathedral of the Moscow Kremlin (1st half of the 14th century, GMMC), traces of a 3-part “fork” have been preserved, indicating that The image was once taken out or had a separate place of veneration outside the iconostasis, while in the surviving inventories of the Assumption Cathedral (from the beginning of the 17th century) it is recorded in the local row of the iconostasis (Inventory of Moscow. Assumption Cathedral. 1876. Stb. 327, 573). As for the external I. of the Assumption Cathedral, according to the cathedral officials of the 17th century, they served as I., located in different parts of the temple, usually in the 2nd north. altar compartments: icons of the Mother of God of Petrovskaya and “Prayer for the People”, both in rich frames, apparently standing at the tomb of St. Peter, Metropolitan Moscow, “in the censer altar” of the cathedral (Ibid. Stb. 326), as well as the icon of Metropolitans Peter and Jonah of Moscow (“above the altar ... the image of Metropolitan Jonah taken out” in a frame and with a face veil - Ibid. Stb. 328). Also in the catholicon of the monastery of St. Neophyte in Cyprus, the iconostasis included previously processional icons of Jesus Christ and the Mother of God (both ca. 1183), on which the remains of handles were preserved. According to K. Walter, before moving to the iconostasis, these icons were located at the throne on the sides of the ciborium (Walter. 1970. P. 164; according to A. Epstein - in front of the iconostasis, on the sides of the royal doors, see: Epstein. 1981. P. 21) . That is, the appearance of external I. could have been influenced by the tradition of their placement in the temple space, when the revered I. who were in the altar (not behind the throne) were carried out not so much to accompany the litiyas, but for the worship of believers.

Our Lady of Tenderness (late 14th century). Double-sided icon (GMZRK)

Our Lady of Tenderness (late 14th century). Double-sided icon (GMZRK)

Vmch. Eustathius Plakida and MC. Thekla (2nd half of the 13th century). Double-sided icon (GMZRK)

Vmch. Eustathius Plakida and MC. Thekla (2nd half of the 13th century). Double-sided icon (GMZRK) In the late Middle Ages, ancient icons began to acquire special veneration, becoming, among other things, double-sided and, probably, external. Thus, on the reverse side of the oldest Ryazan icon of the Mother of God “Hodegetria” (XIII century, RIAMZ) in the 17th century. an image of Equal-to-the-Apostles Constantine and Helen was placed (probably on the sides of the Cross). Obviously, at the same time, a handle with a 3-part “fork” was built into the lower part of the icon board (The Art of the Ryazan Lands. 1993. Cat. 1. P. 18, 25).

However, 2-sided I. cannot always be defined as processional. For a convincing attribution it is necessary to have elements on it that allow it to be made, e.g. marks from rings or “breaks” on the upper or lower parts of the board. Some of the most ancient Russians. 2-sided I., e.g. the Novgorod icon “Savior Not Made by Hands” with “Adoration of the Cross” on the reverse (XII century, Tretyakov Gallery) or the Novgorod icon of the Mother of God “The Sign” with the image of the monk. Juliania on the back (1st half of the 13th century, Tretyakov Gallery, P.D. Korin House-Museum), do not have traces of fasteners on the boards. A long handle with a “fork”, mounted on stands of various types, was also part of the structures necessary for displaying revered I. (Shalina. 2005. pp. 579-583). In monumental paintings, on I. and in book miniatures, Byzantine. and post-Byzantine. time, including in Rus', scenes of processions are presented, in which I. participate. For example, in a miniature from the Sylvester collection (RGADA. F. 381. L. 123, 2nd half of the 14th century) with the image of the prince’s prayer. Before Boris's death, in the center of the tent, on a high handle with a tripod stand at the bottom and a 3-part “fork” at the top, there is an icon with a half-length image of the Savior blessing with his right hand, in his left hand - the Gospel in a red frame. Scenes of miracles performed in front of a small waist-length icon of St. Nicholas the Wonderworker, mounted on a stand with a high handle and a 3-part “fork,” appear in the hagiographic cycles of the saint from the end. XIV century (“The Miracle of the Polovchina” in 2 stamps on the Novgorod icon “St. Nicholas the Wonderworker, with the Life” from the Church of Saints Boris and Gleb in Plotniki, Vel. Novgorod, late 14th century, NGOMZ) and were widely distributed in the 16th century. (for example, an icon from the village of Nenoksa, State Hermitage; for details, see: Shalina. 2005. pp. 575-576, 580; Smirnova. 2007. pp. 196-201, 250-254, 262-264, 298-301) . One of the oldest Russian I., who preserved the device in the form of a 3-part “fork”, should be considered the Rostov icon from c. ap. John the Evangelist on the Ishna with the image of the Mother of God “Tenderness” (late 14th century) on the front side and images of the great martyr. Eustathia Plakida and MC. Thekla (2nd half of the 13th century) on the back (GMZRK, see: Vakhrina. 2003. Cat. 1).

In the miniature from the Chronicle of John Skylitzes (Matrit. gr. 2. L. 172 vol., 12th century) with the scene of the triumphal entry of the emperor. John Tzimiskes in K-pol after the conquest of Bulgaria, one of the oldest images of the outer I. is presented. The icon of the Mother of God with the Child moves on a chariot in front of the army, it is installed on a platform decorated with columns with pommel at the corners, under it - tied in several. There is a wide veil in places. Perhaps the image of the triumphal chariot corresponds to the devices known from the frescoes illustrating the 24th ikos (“O All-Singing Mother”) of the Akathist to the Mother of God, for example. in the paintings of Macedonian monasteries of the 14th century: c. Vmch. Demetrius Markov Monastery (c. 1376) and c. Nativity of the Virgin Mary of the Matejce Monastery (1355-1360). In scenes of the celebration of the Hodegetria icon of the Mother of God, a structure is depicted with wheels attached to the legs; in the painting of the Markov Monastery, the lower part of this “chariot” is hidden by a rich shroud, decorated with circles with embroidered figures of double-headed emperors. eagles, in the painting of the church in Matejce, 4 interconnected legs and a central vertical rod are visible from under the shroud.

"Oh All-Singing Mother." Illustration for the 24th Ikos of the Akathist to the Mother of God in painting c. Vmch. Demetrius Markov Monastery, Macedonia. OK. 1376

"Oh All-Singing Mother." Illustration for the 24th Ikos of the Akathist to the Mother of God in painting c. Vmch. Demetrius Markov Monastery, Macedonia. OK. 1376. The most ancient devices for carrying out icons include those known from written and pictorial monuments associated with the veneration of the icon of the Odigon monastery. Her participation in Tuesday processions is described in detail by pilgrims (XIV-XV centuries). The icon of “Hodegetria” (possibly in the Hodigon monastery) is presented on the frontispiece of the Hamilton Psalter (State Museums of Berlin (Engraving Cabinet). 78 A9. Fol. 39r, ca. 1300). Its surroundings include: a ciborium on columns with a transparent lattice in front of I., lamps, a stand in the shape of a truncated pyramid with a small handle ending in a 3-part “fork”, in the center of the lower field for kissing there is a small copy of the miraculous I., above its upper field a red veil is visible. On the sides of I. inside the ciborium there are people in red robes standing and kneeling, apparently members of the brotherhood of St. I. (Patterson-Shevchenko. 1996. P. 135).

Procession with the Hodegetria Icon of the Mother of God. Fragment of the veil. Workshop led. Kng. Elena Voloshanka. Con. XV - beginning XVI century (1497?) (State Historical Museum)

Procession with the Hodegetria Icon of the Mother of God. Fragment of the veil. Workshop led. Kng. Elena Voloshanka. Con. XV - beginning XVI century (1497?) (State Historical Museum) The cycle illustrating the Akathist to the Mother of God is also characterized by the image of a procession with the Hodegetria icon of the Mother of God, while its removal is depicted in different ways. In the fresco of the Markov monastery, I. is placed on the back of a man bent under its weight, almost hidden by the icon shroud. In most other cases, an image of I. is shown, strengthened with belts on the shoulders or back of a person standing with outstretched arms: fresco c. Our Lady of Blachernitissa of the Blachernae Monastery near Arta (c. 1300); stamp of the icon from the Assumption Cathedral of the Moscow Kremlin “Praise of the Mother of God, with Akathist” (late 14th century, GMMC); sewn veil led Kng. Elena Voloshanka (late 15th - early 16th centuries (1498?), State Historical Museum); fresco in c. Nativity of the Virgin Mary in Ferapontov Monastery (1502).

Another version of the device for external I. - a table or wide bench covered with cloth or shroud - is known from icons depicting the Triumph of Orthodoxy, where the icon of the Mother of God “Hodegetria” is supported on both sides by church servants in festive clothes (c. 1400, British museum, see: Byzantium: Treasures of Byzantine Art and Culture from British Collections / Ed. D. Buckton. L., 1994. Frontispiece; Cat. N 140. P. 129-130; Patterson-Shevchenko. 1994. P. 36- 64. Ill. 3); the same image on the icon “The Presentation of the Vladimir Icon of the Mother of God in Moscow” (mid-17th century, SIHM; see: Smirnova. 2007. P. 155). Similar benches and tables are also known from reports of Officials of the Moscow Assumption Cathedral, Ch. arr. in descriptions of the celebration of the Triumph of Orthodoxy in the era of Patriarch Nikon. On this day, 5 local temple icons were taken out of the Assumption Cathedral, including extremely large ones: the Holy Trinity, the Savior (in 1657 it was the icon of the Savior of Metropolitan Cyprian, in 1658 - the Savior, with St. . Varlaam Khutynsky in prayer"), Our Lady, St. Nicholas the Wonderworker (probably from the Novgorod Vyazhishchi Monastery in the name of St. Nicholas the Wonderworker) and the Great Martyr. Demetrius of Thessalonica (end of the 12th century, from the Cathedral of Demetrius in Vladimir, transferred to Moscow in the end of the 14th century or no later than the 1st quarter of the 16th century). Under these I. on Sobornaya Square. they prepared “dolbas on toes” (benches), upholstered with “red cloth” (Golubtsov. 1908. P. 245). Probably, the “taxes” (lecterns?) were also similar to the tables, on which the external I. were placed in the Cathedral of St. Sophia in Novgorod during the celebration of the New Year, according to the Official of the St. Sophia Cathedral (1626-1634). During the litia, they brought out not the altarpiece (a two-sided icon with images of the Mother of God “The Sign” and the Savior, known from later inventories of the cathedral, see: Inventory of the Novgorod St. Sophia Cathedral 1993. Issue 2. P. 70.- Inventory of 1749), but special icons “Sophia and the Sign, and the Most Pure Vladimir and Tikhvin and towels (tablet icons)” (Golubtsov. 1899. P. 2). Also known in Bulgaria. 2-sided external I., usually large in size, with grooves on the lower field, thanks to the Crimea they were fixed for transfer or installation in place, apparently also on tables or benches (Christian art of Bulgaria. 2003. P. 27) . A special type of device necessary for carrying out the I. should also include the lectern, supplied in the naos in front of the iconostasis (solei) and more suitable for placing the I. on it for the day of the holiday.

Kykkos Icon of the Mother of God Double-sided icon. Con. XII century (Byzantine Museum of the Archbishop Makarios Cultural Center, Nicosia)

Kykkos Icon of the Mother of God Double-sided icon. Con. XII century (Byzantine Museum of the Archbishop Makarios Cultural Center, Nicosia)

Mch. Jacob the Persian Double-sided icon. Con. XII century (Byzantine Museum of the Archbishop Makarios Cultural Center, Nicosia)

Mch. Jacob the Persian Double-sided icon. Con. XII century (Byzantine Museum of the Archbishop Makarios Cultural Center, Nicosia) In Russian. In temples of the late Middle Ages, especially in small towns, external lights were installed in the naos of the temple, on the choirs. According to the Scribe Book of Pskov with its suburbs and counties of 1584/85-1587/88, 2-sided, richly decorated icons, standing “opposite the wing”, were in the churches of Gdov. So, in the cathedral dedicated to the Great Martyr. Demetrius of Solunsky, “opposite the right wing” there was a 2-sided “image of the Incarnation of the Most Pure Ones and Dmitry of the Selunsky fold” (Cities of Russia. 2002. P. 168). I. had a common cover, but both images had their own shroud attached and a lamp was lit. The inventory note that I. was a fold with images of the Mother of God and St. The warrior, patron of the city, resembles the famous Byzantines. examples from the 13th century, e.g. Cypriot 2-sided icon, possibly a diptych, with the Kykkos image of the Mother of God and the martyr. Jacob the Persian (late 12th century, Church of the Theotokos Theoskepasta in Kato Paphos, Cyprus) or a Sinai diptych with images of the Mother of God and Child and St. Procopius (2nd half of the 13th century, monastery of the Great Martyr Church of Catherine in Sinai). In the same Gdov church, opposite the left “wing” there was an icon of the Great Martyr. Demetrius of Thessalonica, also with a butt, behind the throne was the icon of the Mother of God “Hodegetria”. The iconostasis contained an icon of the “Incarnation of the Most Pure Mother of God,” directly called external, with a rich butt, including an embroidered one, as well as a carved gilded wooden canopy above it (Ibid. 2002, p. 169). In another Gdov church - in the name of the Great Church. Paraskeva Friday, a wooden one, standing “outside the city”, against the right “wing” there was “an image of the Incarnation of the Most Pure Ones, on the other side there was an image of a bright Friday on gold.” Above I., as well as in the cathedral of the Great Martyr. Demetrius, there was a carved gilded canopy, a rich butt was attached to the front side with the image of the Mother of God. Next to the external I. there was a local I. with an image of St. patroness of the temple, another external image (“Spasov external on gold” with a butt) stood in the vestibule (Ibid. 2002. pp. 174-175).

II. Iconography of external IDs. Pallas counted 52 2-sided icons, on the front side of which there is an image of the Mother of God “Hodegetria”, on the back - “The Crucifixion”. The researcher called their common protograph and model for subsequent iconography the K-Polish palladium - the miraculous icon of the Mother of God “Hodegetria” from the Odigon monastery (Pallas. 1965. S. 308-322). Shalina divides the surviving 2-sided works (about 70 works were analyzed) into 3 typological groups (Shalina. 2005. pp. 566-567). She includes the most extensive group of icons with the image of the Mother of God “Hodegetria” on the front side and the “Crucifixion” (“Descent from the Cross” or “Lamentation”) on the back. There is a small number of icons with the image of the Mother of God “Hodegetria” on the front side, and on the back - with the Image of the Savior Not Made by Hands (the miraculous Konevskaya Icon of the Mother of God, late 14th century, not preserved) or Christ in the Tomb (late 12th century. , Byzantine Museum, Kastoria). A separate group consists of icons with the image of the Mother of God (or the Savior) on the front side and the image of the holiday on the back, for example: a K-Polish icon from c. Our Lady of Perivelept in Ohrid with the image of the Mother of God and the epithet “Ψυχοσώστρια” (Soul Savior), in a precious frame, on the front side and with the “Annunciation” on the back (early 14th century, Icon Gallery, Ohrid); icon from the Assumption Cathedral Vel. Ustyug with the image of the Mother of God “Hodegetria” and saints in the margins and with the “Epiphany” on the back (c. 1558, VUIAKHMZ), probably repeating the icon sent for the consecration of the 1st building of the cathedral in 1290. To the 3rd group Shalina attributes I. with images of the Mother of God on the front side and a saint (or saints) on the back, for example: a Novgorod icon with the image of the Mother of God “Hodegetria” on the front side (3rd quarter of the 14th century) and the martyr. George on the back (mid-2nd half of the 11th century, GMMK).

Our Lady "Hodegetria" Double-sided icon. Con. XII century (Byzantine Museum, Kastoria)

Our Lady "Hodegetria" Double-sided icon. Con. XII century (Byzantine Museum, Kastoria)

Christ in the tomb Double-sided icon. Con. XII century (Byzantine Museum, Kastoria)

Christ in the tomb Double-sided icon. Con. XII century (Byzantine Museum, Kastoria) Statistics of surviving monuments and analysis of their program show that the 12th century, to which the largest number of them belongs, was a special time in the history of portable monuments (see: Shalina, 2005, p. 565). However, it is unclear whether the development of the iconography of external icons was consistent, or whether different programs developed simultaneously. Grabar believed that the composition “Crucifixion” or related “Mourning” and “Worship of the Cross” replaced the image of the Cross, previously the only design option for the reverse side of I. One of the oldest two-sided external icons in Bulgaria. origin from c. in the name of St. Nicholas the Wonderworker in Melnik has on the front side images of the Mother of God “Hodegetria”, archangels and scenes of the “Annunciation” (beginning of the 13th century), and on the back there is a complex of plots: “The Descent from the Cross”, “Lamentation” with scenes from the NT ( end of the 12th century) (see: Bakalova. 2002. pp. 64-65, 67-68).

However, the iconographic repertoire of external icons, primarily 2-sided, especially late Byzantine. time (XIII-XV centuries), much richer than the typologies outlined by researchers and more difficult to classify. Quite early, rare versions of double-sided icons appeared with images of saints on both sides (an icon with a relief image of the Great Martyr George surrounded by picturesque hagiographic scenes on the front side and Saints Marina and Irina (?) in prayer to the Savior on the back, 2nd floor 13th century, Byzantine Museum, Athens), or with images of saints on the front side and the “Crucifixion” on the back (“Saints of Jerusalem and 3 Youths. Crucifixion”, 3rd quarter of the 14th century, Byzantine Museum, Athens), or with an image of a saint on the front side and a plot scene on the back (“Martyr Catherine. St. Zosimas giving Holy Communion to St. Mary of Egypt,” 2nd half of the 14th century, Byzantine Museum, Athens).

There are known external icons with images of the Mother of God on both sides, usually from different times (an icon with the image of “Hodegetria” on the front side (c. 1315, icon painter George Kalliergis?) and “Hodegetria” with the epithet “Παμμακάριστος” (Most Blessed) on reverse (2nd half of the 16th century) or an icon with the image of “Tenderness” (c. 1400) on the front side and “Unfading Color” (1st half of the 18th century) on the back (both - Byzantine Museum, Veria It is possible that the appearance on the back of the Virgin Mary of the image of another version of the I. Mother of God, as well as traces of devices for removal, may be associated with the development of veneration, in particular in Veria, of the ancient I. and with a change in their role in liturgical practice. veneration of a separate icon could bring to life such a phenomenon as the creation of icons, in the front part of which an ancient revered image was included as a spiritual and pictorial “core.” Such, for example, is a two-sided icon of the late 15th century. depiction of Christ, archangels, apostles and holy warriors on the front side, framing a smaller icon (ser. XIV century) with images of Christ and the Mother of God with the Child, with worshiping angels and St. John the Baptist; on the reverse - “Crucifixion” (monastery of Vlatadon, Thessalonica; according to A. Turta, I. was the main processional image of the monastery, see: Τούρτα Α. Εικόνες από το σκευοφυλάκειο της Ιεράς Μονής Βλατάδων // Χριστιανική Θεσσαλονίκη: Απόης ?? ωμάνων, 1430. Θεσσαλονίκη, 1992. Σ. 175-186).

The iconographic program of worshipers of I. of the late Palaiologan period received additional accents and a broader semantic context due to the combination of a revered image in the center with a frame, for example. scenes of the holidays, as can be seen on the 2-sided icon with the image of the Mother of God with the Child, accompanied by the epithet “῾Η Παῦσον Λύπη[ν]” (Ease sorrow) on the front side, which is surrounded by 10 compositions of the holidays. On the back - traditional. for most 2-sided “Crucifixion” icons with figures of prophets in the margins (3rd quarter of the 14th century, Greek Patriarchate, Istanbul). A. Weil Carr, relying on the rare epithet of the Mother of God image, connects it with the K-Polish monastery of the same dedication, founded in the middle. XIV century (see: Byzantium. 2004. P. 167-169. Cat. 90).

Our Lady “Hodegetria” (beginning of the 13th century) Double-sided icon (Byzantine Museum, Veria)

Our Lady “Hodegetria” (beginning of the 13th century) Double-sided icon (Byzantine Museum, Veria)

Our Lady “Hodegetria” (2nd half of the 16th century) Double-sided icon (Byzantine Museum, Veria)

Our Lady “Hodegetria” (2nd half of the 16th century) Double-sided icon (Byzantine Museum, Veria) Complex, unique programs of external images in the late Byzantine period. time were, as a rule, associated with the order of the donor, who relied on the power of the prayers of those saints, whose images were reproduced on the icons he ordered. Yes, ok. In 1363, for the monastery of Pantocrator on Mount Athos, a series of I. of the highest quality and with a special program were created, which expressed the idea of saving their customers. On the icon of Christ Pantocrator (c. 1363, GE) in the lower corners of the side fields are depicted the kneeling figures of the donors of the monastery, the brothers John, Vel. primikiriya, and Alexei, led. stratopedarcha. Two double-sided extended Is date back to the same time. The icon with the image of Christ Pantocrator on the front side is of the same type as on the icon from the State Hermitage, which is extremely close to it in style; on the back - St. Afanasy Afonsky. On the front side of the other I. there is a half-length image of St. John the Baptist with a staff topped with a small medallion with the image of Jesus Christ; on the back there is a composition in which St. John the Baptist, standing in front of the Mother of God with the Child in her arms, points with his right hand to a bowl with a truncated head at the feet of the Mother of God.

One of the striking examples of the complication of the remote I. program is the icon from the monastery. John the Theologian near the village. Poganovo to the southeast. Serbia (Thessalonica, between 1371 and 1393, NHG, Crypt) with figures of the Virgin Mary “Καταφυγή” (Refuge) and the ap. John the Evangelist on the front side and the composition “Vision of the Prophet. Ezekiel" (the so-called Miracle in Latom) on the back. Figures of the Sorrowful Mother of God and St. John the Evangelist go back to the composition “The Crucifixion”. The humility of the customers was reflected in such a technique as the placement of the prayer signature (preserved fragments) on a golden background just above the soil, at the feet of the Mother of God and the Apostle (about the creation of I. for participation in the annual services of remembrance of saints, see: Pentcheva. 2000. P . 139-153). In the choice of epithets and iconographic version for the reverse side of I. they see an orientation towards the shrines of Thessalonica, where the place of martyrdom of the great martyr. Demetrius of Thessaloniki is called “katafigi”, and in the altar of the Hosios David (Latomos) monastery there is a mosaic composition (last quarter of the 5th century), based on the “Vision of the Prophet. Ezekiel."

In Russian The tradition of writing remote icons is marked by a kind of “historicism,” when ancient editions of icons and images of saints belonging to the same era were chosen for both sides. Thus, on the front side of a 2-sided icon from the Rostov c. Saints Boris and Gleb (GMZRK) in the 15th century. The Vladimir Icon of the Mother of God was painted, and on its back in the 16th century. life-size figures of the princes Saints Boris and Gleb were depicted on either side of their father, St. book Vladimir (Vakhrina. 2003. Cat. 39). Probably, the choice of such subjects was connected not only with the dedication of the throne, but also with the desire to glorify the ancient Russians in Rostov. holy princes and the icon of the Mother of God, which Prince. Andrei Bogolyubsky took him from Kievan Rus to the Rostov land.

History of the Orthodox icon

Prototypes of icons in the form of symbolic drawings appeared in the first centuries of Christianity. By the 4th century, church paintings depicting Jesus Christ, the Mother of God, and scenes from the Bible became widespread. At the same time, according to one of the most common versions, the first icons appeared in Egypt.

In the 8th century, the iconoclastic heresy (false teaching) arose against the veneration of icons. It was based on an incorrect perception of the Old Testament prohibition on the creation of idols. However, in 787, at the Seventh Ecumenical Council, the dogma of icon veneration was adopted, and the theological meaning of the icon was formulated. Icon veneration was finally established in the middle of the 9th century, at which time certain icon painting canons were formed.

The tradition of painting icons penetrated into Rus' in the 11th century. Some of the most famous Russian icon painters were Gregory the Iconographer, Theophanes the Greek, and Andrei Rublev.

The meaning of the word Icon according to the Symbolism Dictionary:

Icon - Symbolizes the microcosm. Its colors should be pure, and the golden background symbolizes light, the Grace of God and God himself as the basis of everything. Its components and materials represent the manifest world, including the animal, plant and mineral kingdoms, and reflect the interconnectedness of all created things. The icon has a sacred meaning in the sense that it is an external and visible sign of internal and spiritual Grace, a channel transmitting the Grace of God. In the Eastern Church, the iconostasis divides heaven and earth vertically with an arch, symbolizing Heaven, and sides and a base, meaning Earth. and also horizontally, separating the chancel from the nave. Here is the border between the holy and the profane, divine and human.